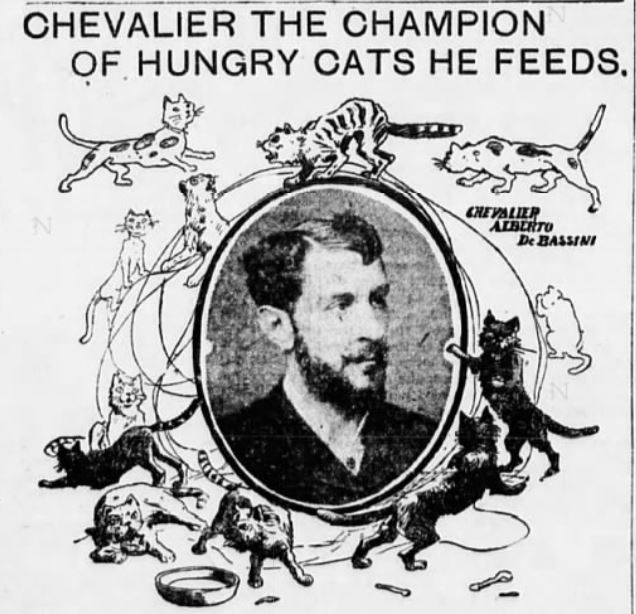

“No cat ever saw the kindly face of the old tenor, now a teacher of music, that it did not purr pleadingly at his heels and receive a welcome.”–New York Times, October 22, 1908

Alberto Gaston de Bassini, aka the Chevalier, was a man who truly loved and cared about cats. He rescued them, fed them, bathed them, and sang to them, and named them after heroes and heroines from famous operas.

Unfortunately for de Bassini–and the cats–his wife and daughter were not fond of felines. Neither were his neighbors or his fellow tenants at 171 East 91st Street in the Carnegie Hill section of Manhattan.

When an inspector from the Health Department paid a visit to de Bassini in June 1902, he found about 17 cats in the backyard and about 11 cats lounging on the mantelpiece and dining room table inside the ground-floor apartment.

Neighbors told the inspector that de Bassini had as many as 35 cats in a room he had established for them in the basement of the building. (And this is only Part I of the story, so this was only the start of this crazy cat man’s obsession with felines!) The neighbors complained that the cats were giving them insomnia and making their lives miserable.

The Cat-Man Chevalier’s Early Life

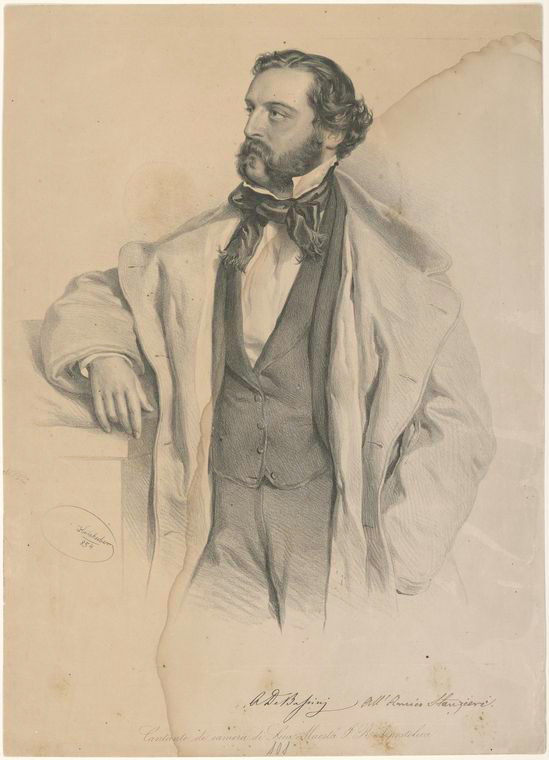

Born in Florence, Italy, around 1847, de Bassini was the son of Achille de Bassini, a famous Italian baritone, and Rita Gabutti, a popular soprano. His godfathers were Giuseppe Verdi, the renowned Italian opera composer, and Prince Jozef Poniatowsky of Poland.

Although his parents had intended for him to join the Italian navy, they discovered that Alberto had inherited their musical gifts when he filled in for a singer who had fallen ill prior to a performance at a little theater in Naples. During his successful career, de Bassini served as the court singer to King Louis I of Portugal and was a leading tenor (and later, baritone) with numerous prima donnas of the grand opera. (It was the king who gave him the title of Chevalier of Portugal’s Military Order of Christ.)

(Click here to hear a 1902 recording of de Bassini singing.)

In 1878, de Bassini married his wife, Emma, a young singer from Louisiana. Sometime around 1896, when their daughter, Vera, was still a young child, the couple moved from Italy to New York City. Alberto found work singing grand opera at the Metropolitan Opera House.

The musical couple originally lived at 135 West 66th Street, but by 1900 they were living and teaching voice and piano lessons to upper-class girls and women in their little flat on East 91st Street.

Too Many Cats

In June 1902, de Bassini received a summons to appear at the Yorkville Police Court on nuisance charges. One or more neighbors had filed an official complaint against the Chevalier, who said it was spiteful to complain about his feeding a clowder of starving cats that had been abandoned by their owners when the thoughtless humans traveled to the country for the summer months.

According to numerous news accounts, Madame de Bassini had been serving midday lunch to about 17 felines in the backyard of their home when a young man from the Health Department served the summons. The health officer told de Bassini that the charges would be dropped if he would remove the cats from the premises.

The Yorkville Police Court at 152 East 57th Street was constructed around 1862. This building was demolished 100 years later, in 1959, to make way for two large apartment buildings at 153 and 157 East 57th Street. These buildings were converted to condos in 1986. Cats are reportedly welcome in the condos but dogs are not.

When the officer refused to tell the Chevalier who filed the complaint, de Bassini said he would go to court just to find out who was complaining about him and his cats. He also said he wanted to find out if it was against the laws of the state to feed a starving animal that did not belong to you.

During his initial court arraignment, de Bassini dramatically declared that he would not employ counsel to defend him. He also said he was willing to go to the electric chair in defense of his right to feed all the cats he wanted to save.

“I am an old man, but I am not yet too old to fight, and would be willing to meet the individual who was heartless enough to object to my feeding a few poor, starving cats, de Bassini told the judge. “To ze jail you send me I will suffer for ze cats. Yes, I say, to the what you call it, the electric chair, you send me I will suffer for the cats.” (Some news articles incorporated his Italian dialect into direct quotes while other anglicized his speech.)

De Bassini explained that when the butcher came at noon to deliver meat for his own six or seven cats, other starving cats in the neighborhood would show up to see if they could share in the bounty. “The butcher wagon it stop. Then it go away. After it go away I look out the back window and I see pussy there, pussy there and there. I see pussy everywhere.” He said the cats knew it was safe to gather in his yard because he did not kick or otherwise hurt them.

De Bassini continued, “It is impossible for me to witness animal suffering. I could not see those cats starve. To feed them is kind, to see them not feed it is very brutal.”

He told another reporter, “What to ze cat I must say? Oh! It is so ridiculous. I must shake my finger, so, and say to ze cat, ‘I do not like you, Mr. Cat, for because it is ze law.’ It is ridiculous.”

The Chevalier also said that none of his numerous female singing students had ever complained about his cats when they came to his house for lessons, so the cats could not really be that much of a nuisance.

In what the Buffalo Times described as “a gymnastic exhibition of his indignant feelings,” de Bassini told the judge, “I intend to keep my cats and to feed them too. If New York City will not let me do it on the island of Manhattan then I shall move off the island. If I am further persecuted because I believe in alleviating animal suffering wherever possible, I shall move to Peekskill and take my cats with me to spend the summer there.”

Because de Bassini was so visibly upset that the complainant did not show up at court, Assistant Corporation Counsel Frederick W. Steele, representing the Department of Health, asked Judge Josephs to postpone the court date for June 12. Steele also told the judge that the extra week would give time for de Bassini to “abate the nuisance.”

As he left the Yorkville Police Court, de Bassini told reporters, “I do not see the complainant and I am very sad. It is not a man I know, but if it is a man I will take pleasure the man’s face to slap.”

He also said that he thought one of the neighborhood women filed the complaint. According to the Chevalier, one day he came to the rescue of a sick cat in a neighboring yard by breaking down a fence. The woman who owned the house told him to let the cat die. “I look at her and say, and I say it hard, too, ‘Let you die, too.”

One reporter reportedly asked de Bassini if his wife could have filed the complaint. The Chevalier responded, “It is true that my wife does not like cats. She is an American, we being married in New Orleans nineteen years ago, and I am an Italian. She recognizes the Code Napoleon, and would not dare to have me brought to court, only in case she was seeking a divorce. It is impossible to suspect her of doing anything of the kind.”

A Feline Free-for-All

In order to comply with court orders, de Bassini created a flyer to let everyone know that he was going to give up all of his “educated and distinguished pussy-cats” to those who were kindhearted. By noon on the day of the cat giveaway, 91stt Street was alive with cat hunters. By 4 p.m., more than 100 people had reportedly come in search of a free musical cat.

As the Baltimore Sun noted, “Women made East Ninety-first street look like the shopping district at a spring opening today in response to the advertisement of the Chevalier Alberto de Bassini.”

As women cooed and chirped in his cat nursery, many of the cats hissed and spat and growled or scratched at their future mistresses. According to the New York World, six protesting cats were carried yowling away to other homes; four fled over back fences “to escape the anguish of separation from their benefactor;” and one feline made himself “so actively disagreeable to all callers that none dared risk his adoption.”

Some of the adopted cats included a six-toed cat named Otello, a sinuous tiger cat, a maltese named Margherita, a yellow cat named Rhadames, a quiet cat called Chanato, and a striped feline named Aida. One little girl who wanted to have a kitten with an operatic name ignored a beautiful fat cat named Pico and selected a less beautiful cat name Faust.

Another woman insisted on a white cat, to which de Bassini said, “My only white one is away. Perhaps my daughter—” His daughter quickly interrupted, “Papa, I cannot climb the back fence.” The Chevalier promised the woman that when the white cat returned he would give it to her.

At the end of the day, only the troublesome cat and two tiny kittens that were too young to leave remained. “It is not one tragedy? Ten here this morning and now but my Chipi, this dear Mignon and the naughty Bella. I shall no longer make my little hospitalities to the poor pussies. They are gone, my cats. Me, too. I will soon be gone.”

Despite what he told the press, de Bassini stayed in New York City for many more years, albeit, not on East 91st Street. An article in the New York Times in 1908 stated that he was living at 111 East 96th Street, and according to the 1910 census, he and his wife and daughter were living in East Harlem in a brand-new six-story tenement building at 1590 Lexington Avenue that year.

In Part II of this cat-man tale of Old New York, I’ll tell you about some other adventures with de Bassini and his cats, and provide a short history of Carnegie Hill, the neighborhood where he lived.

I enjoyed this story very much. The Chevalier sounds like a kind and passionate man.

I’m glad you enjoyed it. He really was kind to the street cats, which was very rare for those times. Part II will be coming soon.

This man is my hero!

I love him too! Part 2 of the story is coming tomorrow, so stay tuned!