“This is the most extraordinary thing I ever heard of,” Magistrate Alfred E. Ommen told Policeman Levy, after Levy had finished explaining why he arrested a man for intoxicating cats with catnip powder on the corner of Avenue B and Fifth Street.

“I was walking through Fifth Street on Sunday evening,” Levy said, “when I saw a crowd of people at the corner of Avenue B. In the circle was this man, with a circle of all sorts and conditions of cats sitting around him.”

Levy said the cats were tumbling and rolling over and over, all fighting over the catnip powder that the man, Joseph Weiss, had sprinkled on the pavement.

As the cats began to gather from the neighboring roofs and basements, Joseph started to lead his feline following along Avenue B toward Houston Street.

According to a reporter for The New York Times, “Although Weiss walked steadily, the cats staggered like the Bowery after midnight, and emitted a maudlin caterwauling.”

Several people in the crowd yelled to Policeman Levy to arrest Joseph Weiss for disorderly conduct. Levy did charge Weiss with disorderly conduct, “although he admitted that the man was not nearly as disorderly as the cats, which the prisoner had intoxicated with catnip powder.”

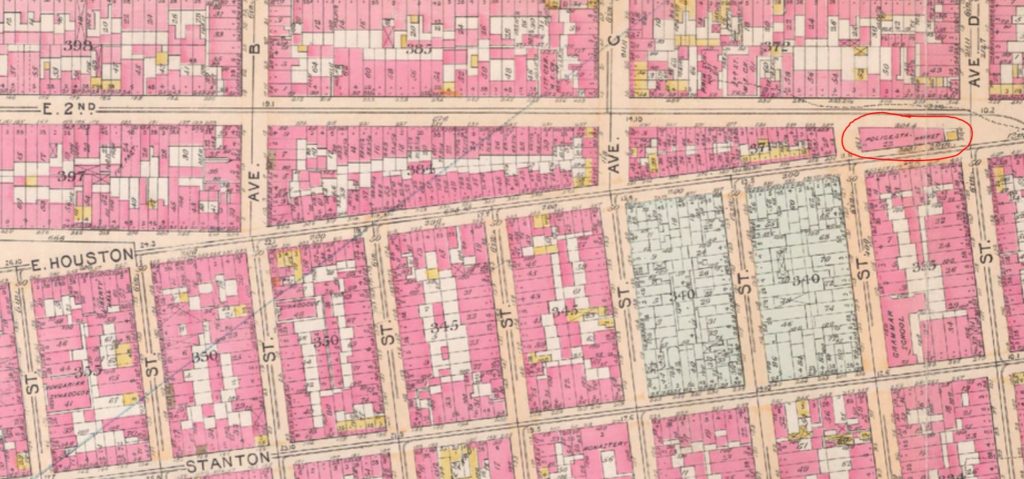

As Levy lead Weiss toward the Union Market police station at East Houston and Sheriff Streets, the cats followed right along, not about to lose sight of the man who had served up their drug of choice. They even followed the men into the station, where a doorman spent the rest of his shift searching for them in the cells and “chasing them off the roof with a mop, lest a shower of acrobatic cats disturb passersby.” (Sadly, the doorman eventually resorted to squirting the cats with a hose to get them to leave the station.)

During his hearing before Magistrate Ommen at the Essex Market Police Court, Joseph begged for mercy, saying that he was innocent of intent to intoxicate, and did not know what effect the powder would have on the cats. He also explained that a friend had told him that he could hypnotize cats with the catnip power.

Justice Ommen–who one year later would decide in favor of a cat-hoarding woman in the Yorkville Police Court–told Levy he did not buy his poor excuse. “You knew, all right,” the judge told Joseph. “I’ll fine you $5 this time, and next time you collect a stack of cats and create a furore on the street I’ll fine you more.”

A Brief History of the Union Market Police Station

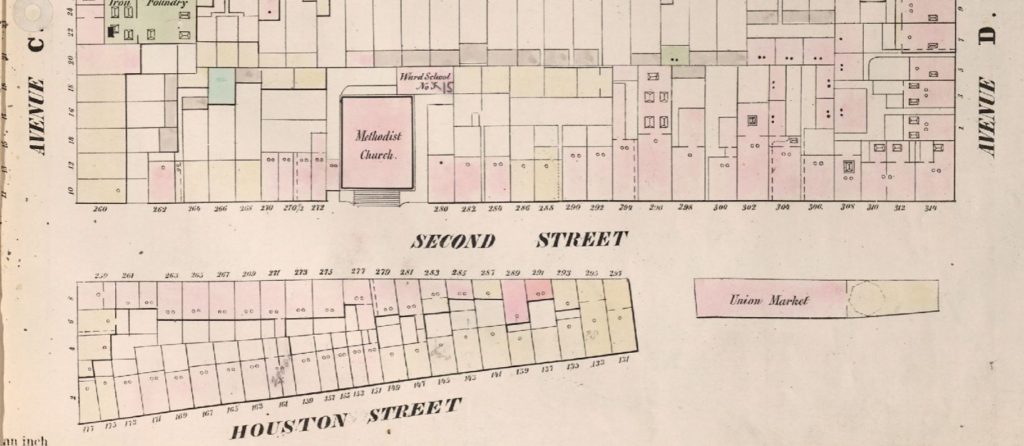

In 1834, the city’s Market Committee proposed constructing a market on the triangular lot bounded by East Houston Street (then still called North Street), East Second Street, and Avenue C. The lot was appraised at $8,000, and the committee signed a contract with Charles Overton to build the market at a cost of $5,961.

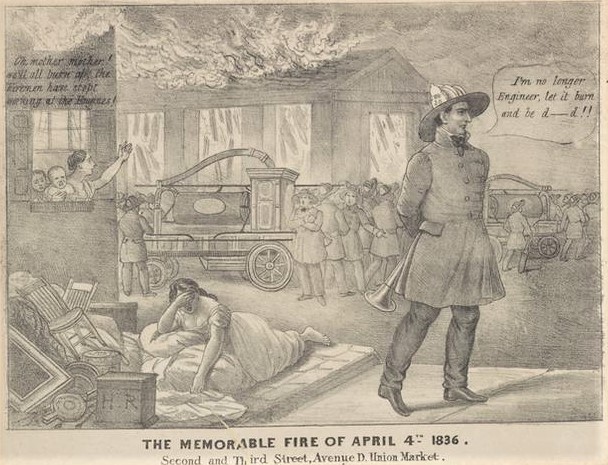

The original market had stands for six butchers; more stalls were added in 1836. As was par for the course for many of the city’s early buildings, a fire in the spring of 1836 consumed most of the market, along with about 20 other buildings on Avenue D, Second, and Third Streets.

According to reports, the fire had started in White’s and Poulson’s carpenter shop at 304 Third Street and quickly spread, destroying tenements, the market, and the fire bell tower. The market building was a total loss, albeit, the stalls, fixtures, and meats were saved before the fire had reached it.

During the fire, the firemen “flipped their caps” (they turned their hats around) and went on strike, refusing to perform their duties in protest to the firing of Chief Engineer James Gulick. (The men learned that Gulick had been replaced by J.R. Riker during the fire.) The firemen refused to suppress the fire until Gulick had been reinstated. According to news reports, the quarrel resulted in about $300,000 worth of property damage.

Firemen flipped their caps and went on strike during the Union Market fire of 1836, resulting in the loss of many buildings on Avenue D, Second, and Third Streets.

The following month, the city appropriated $3,000 to rebuild the market and the Fifth District Watch House. About 20 years later, in 1853, the city spent $20,000 to construct a much larger building that could also accommodate a police station for the Eleventh Precinct on the upper floors. The market section of the new building accommodated 18 butchers, 26 hucksters, and several fishermen and butter dealers who had been located on overflow sheds on vacant ground east of the smaller old market building.

The fire bell tower at the Union Market would have looked similar to this bell tower at Truck No. 1 station in Stapleton, Staten Island. At one time, 14 policemen were assigned to the various fire towers throughout the city as bell ringers. The tower system in Manhattan was replaced by a telegraph system on November 15, 1865. The new system comprised all the main machinery at police headquarters on Mulberry Street and four lines of wires for the East, West, South, and North districts.

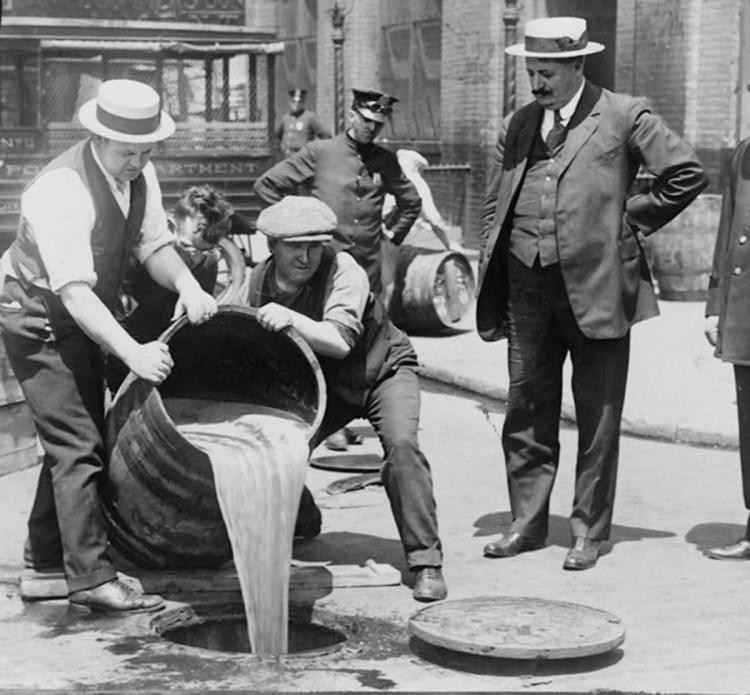

In 1864, the Union Market building was reconfigured again to serve primarily as a police station, with only the eastern end dedicated to market purposes (as shown in the 1895 map above). The city shut down the police station (then known as the Seventeenth Precinct) in 1921, although it continued to use the building as a storage facility for all the malt, spirits, and other liquors confiscated by the police during the Prohibition era.

In fact, in June 1921, Deputy Police Commissioner John A. Leach officiated at a “funeral” for the liquor, in which numerous barrels and bottles of alcohol were opened and poured down a manhole on Sheriff Street, turning the East River into a $50,000 cocktail.

In 1931, Police Commissioner Edward Pierce Mulrooney reopened the Union Market police station and placed Captain Jerome A. Foley in command. The new precinct was home to a new Eleventh Precinct made up of police officers from the nearby Clinton Street and Fifth Street police stations.

The Union Market police station at 130 Sheriff Street, also known as the Sheriff Street Station, as it looked around 1940.

When the city widened East Houston Street in the late 1950s, all the buildings on the north side of the street–including the old Union Market building–were obliterated, creating numerous empty lots and leaving the back of the tenement rows along East Second Avenue exposed until development picked up in later years.

If you enjoyed this cat tale, check out another catnip caper that took place in 1909 in East Harlem!

Very Interesting. I used to live near the site of the catnip party.