One dog on a hot day, and one cat on a hot night can do much to arouse a neighborhood, but when man tries to conceive of the pandemonium attaching to twenty-five dogs and thirteen cats, the imagination meets its Waterloo.”—New York Morning Tribune, June 19, 1899

The Cats and Dogs Survive a Fire

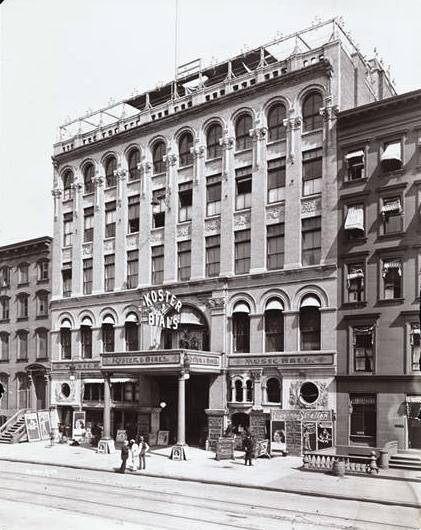

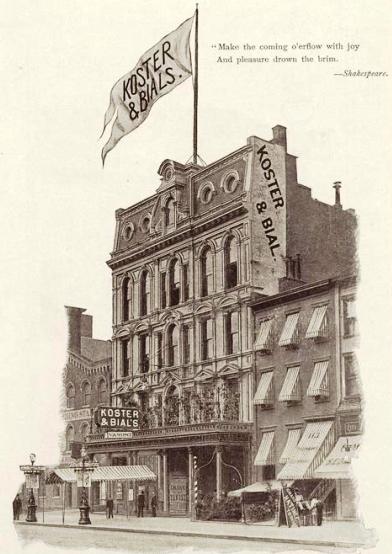

On Sunday morning, June 18, 1899, Charles Randolph, a porter with Koster & Bial’s Music Hall at 135 West 34th Street, noticed flames coming from the stage on the theater’s rooftop garden. Randolph and some other men who were getting the theater ready for a performance that evening grabbed a standpipe hose and tried to put out of the flames. Although the hose was attached to two large water tanks, the water was not enough. Soon the fire was out of control.

Randolph ran down the street and pulled the fire alarm. Engine Company No. 1 on West 29th Street was the first company to respond, followed by numerous other companies that responded to second and third alarms for the fire at Koster & Bial’s.

Manager Alfred E. Aarons, who lived just three doors from Koster & Bial’s Music Hall, also responded to the scene. His very first concern was for the approximately 25 dogs and 13 dogs belonging to Leonidas Arniotis. The animals were scheduled to perform their popular sold-out circus act on the rooftop garden that night.

According to one account in the New York Times, the animals were locked inside cages near the rear of the stage in the main auditorium of the building. Aarons reportedly opened a cage occupied by two Great Danes who in turn leaped out and knocked him down. He then opened all the other cages, and soon the dogs were running all over the theater seats. The cats refused to budge from their cages (what a surprise).

Within minutes, the animals’ trainer appeared on the scene and blew his whistle. All the cats and dogs immediately came to him, allowing him to lead the animals safely out the door and to the street. Not one animal was lost in the chaos.

Another news account in the New York Tribune reported that the animals were all in cages in the rooftop garden, near the origin of the fire. This article claimed that the animals were running loose on the roof, and that several firemen were bitten by the dogs. The firemen turned their hoses on the dogs to subdue them, while the cats reportedly climbed up the smoking scenery and scaled a high wall to find refuge on the tops of adjoining buildings.

The latter news account provides a much more entertaining picture, but because the two newspapers reported the event so differently, I have no way of proving which story was correct. Either way, all the animals were saved, so that’s all that matters.

As for the fire, the firemen were able to turn four hose streams on the stage and scenery in order to douse the flames. The fire didn’t penetrate below the roof so there was no damage to the interior. Workmen spent all day making repairs and constructing a new temporary stage so that the great dog and cat circus could go on as planned that evening.

Leonidas Arniotis’s Great Dog and Cat Circus

“I train my dogs and cats by kindness and patience—oh, so much patience! The main thing is to get them to understand what you want them to do, and then they do it quickly enough. Dogs have more reason than cats and are far easier to train. Cats are, like women, capricious. One must coax them all the time. If you let a cat know that you are trying to make it do a thing, it won’t do it. One must be always kind to them.” –Leonidas Arniotis, in Pearson’s Magazine, Vol. 5, 1898

The cats and dogs were owned and trained by Professor Leonidas Arniotis (1862-1939), a Greek entertainer and former horse trainer who had been showcasing his animals in North America for the past two years. Leonidas had arrived in New York City on March 22, 1897. Almost immediately, the entertainer took New York City and other American cities by storm with his troupe of talented cats and dogs.

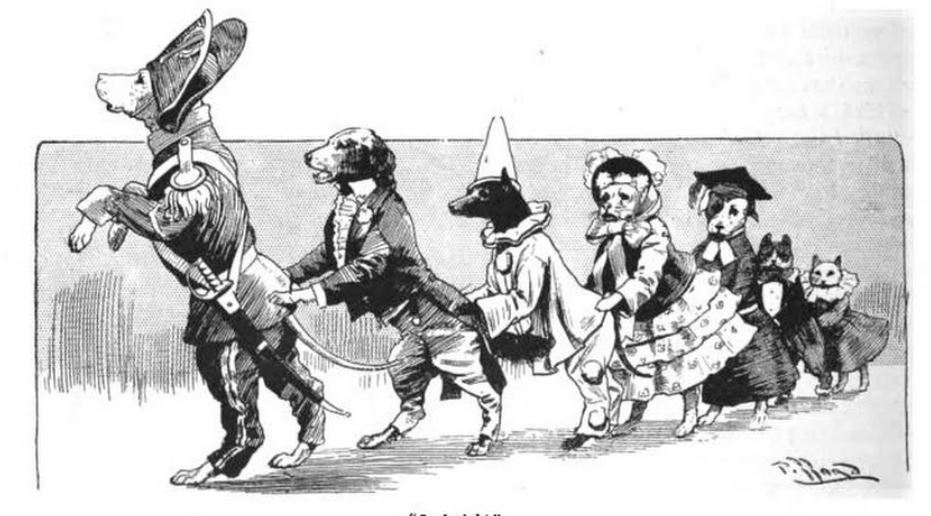

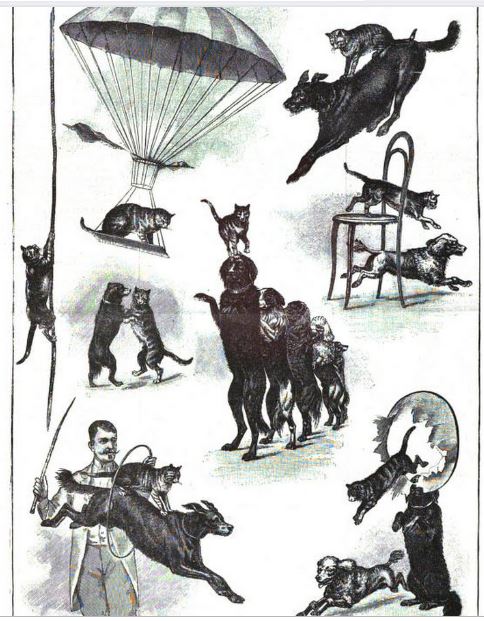

Leonidas Arniotis had an international four-legged troupe that featured about two dozen dogs, including a Great Dane who served as porter and ringmaster, a Siberian wolf hound, a French poodle, a St. Bernard, a Newfoundland, and a hairless little dog from Mexico.

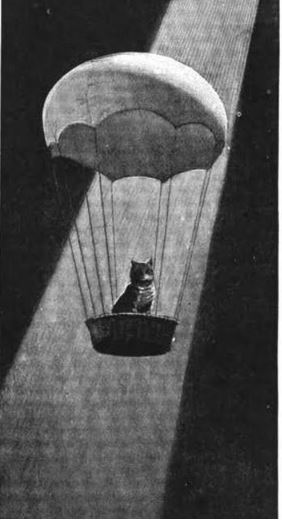

Although he admitted that he would prefer to train 20 dogs than just one cat, he also had about a dozen cats, including a “feline aeronaut” who dropped to the stage in a parachute. According to Leonidas Arniotis, all the animals lived in baskets and curled up “together in hearty good fellowship.”

Leonidas said he fed his animals every day at 4 p.m. (not only did the cats get the best meat and milk and soup, but they were also allowed to go foraging for mice in the theaters sometimes.). He did not believe in using hunger as a training method, because he believed they did better work with a full belly. He only “rarely” whipped his dogs but he “wouldn’t dare punish the cats at all.” As he explained, “Why, I believe if I struck one of those cats she would never act again.”

One of the favorite acts featured the dogs acting as horses and the cats as riders. The dogs would trot around the ring, and then, while they were passing under two stools, a cat would spring onto the dog’s back. Leoniadas Arniotis explained that because the cats used their claws at first to get a good grip, it took him months to teach them to hold on by the pressure of their legs instead of by their claws.

Cerberus and Mimisse, the Stars of Leonidas’ Circus

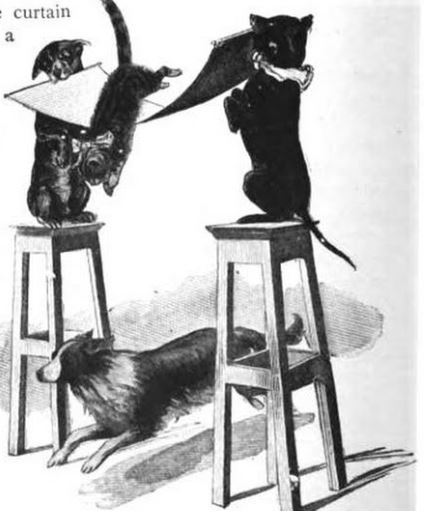

Another show-stealer featured a Parisian cat named Mimisse, who dropped from the stage’s proscenium arch in a parachute. According to one news report, the cat was trained to climb a rope all the way to the top of the stage, walk out onto a platform under the parachute, step into the parachute basket, and, “with a look of supreme indifference at the audience below,” pull a trip rope and sail “majestically towards the stage.”

After Mimisse (aka Pippina) reached the stage, she was met by her partner, a black spaniel named Cerberus who was wearing his best evening dress. The two would do a short comedy act, as described in the March 6, 1897 issue of Scientific American Supplement:

“A comic scene which follows is a triumph in animal training. ‘Cerberus’ is chained at the left side of the stage. ‘Pippina’ takes her place on a chair at the right, and Mr. Arniotis is seated at a well covered table in the center, ready to eat his supper. He has nothing to drink, and, as there is no one to wait on him, he is obliged to go for it himself.

After he has left the stage Cerberus slips his collar off, climbs up on the table and eats the entire meal. As he is swallowing the last mouthful a thought comes to him of the punishment that must follow, and he looks to his friend to help him out of his difficulty. Pippina is then taken by the collar and set on the table, where she remains looking sad, while Cerberus resumes his collar. Mr. Arniotis returns, is suspicious of the unhappy victim sitting among the empty dishes, and is about to punish her, when she climbs on her master and whispers in his ear that Cerberus is the real culprit. Pippina’s innocence is established, [the Great Dane appears and arrests the dog], and the audience thanks the performers with a round of applause.”

According to Helen M. Winslow, author of Concerning Cats: My Own and Others (1900), Leonidas acquired Mimisse while studying in Paris. One day, according to the story, he was standing on a bridge over the Seine when he witnessed a man tossing a cat into the river. Leonidas winked at Cerberus (the first dog he ever trained), who immediately jumped into the river and seized the cat by the nape of her neck. This was not the dog’s first rescue: he once jumped into a river to save a child who had fallen into the water, and was thereafter trained to dive for Leonidas’ purse when he dropped it into 15 feet of water.

The two animals became inseparable and performed many tricks together, albeit, Leonidas said it took him three years to train the cat by using flattery and extensive petting. For the parachute trick, he said he first taught Mimesse how to open an enter a basket that the Great Dane held in his mouth, and then he let the parachute down very slowly at first until she was comfortable with faster speeds. (He reportedly also had a German cat named Marguerite who could also perform the parachute trick. Perhaps she was the understudy.)

I’m not sure when Leonidas Arniotis stopped the Great Dog and Cat Circus, but I assume it was sometime around 1900, when the last ad for his circus at the London Hippodrome appeared in newspapers. According to the Hellenic Institute, Leonidas Arniotis spent the last years of his life in London, where he owned a bookshop and cafe in St. Giles’s High Street.

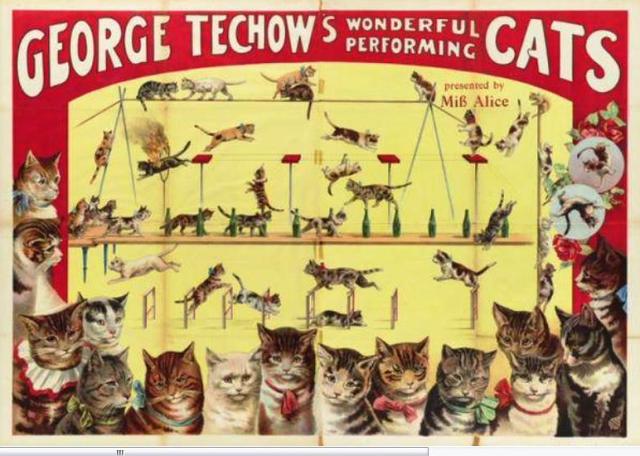

If you liked this story, you may enjoy reading about Herr George Techow, who performed with his cats in the late 1800s.

For more history-related information about Koster & Bial’s Music Hall, you may enjoy reading about the boxing kangaroo that performed at their theater on 23rd Street in 1893.

I have often wanted to travel back in time, especially to the late 19th or early 20th century. Reading this makes me long to do that even more. This show sounds amazing and adorable – and I love that cruelty wasn’t the training method used. I also think it’s so wonderful that all of the animals were saved from the fire and that they were what mattered – the firemen tried to save them even before Arniotis arrived on the scene. The only thing I don’t get is, why did Arniotis stop his circus, and what happened to the animals afterwards? I hope he kept them and they got to run his bookstore with him! Thanks for another delightful read!