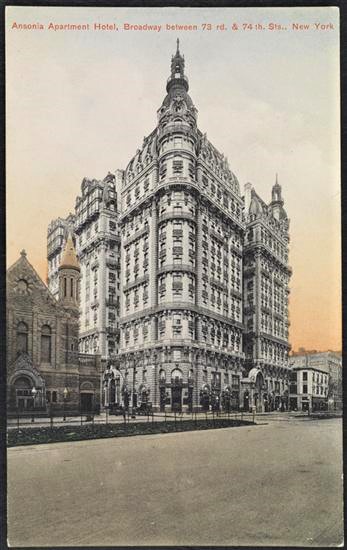

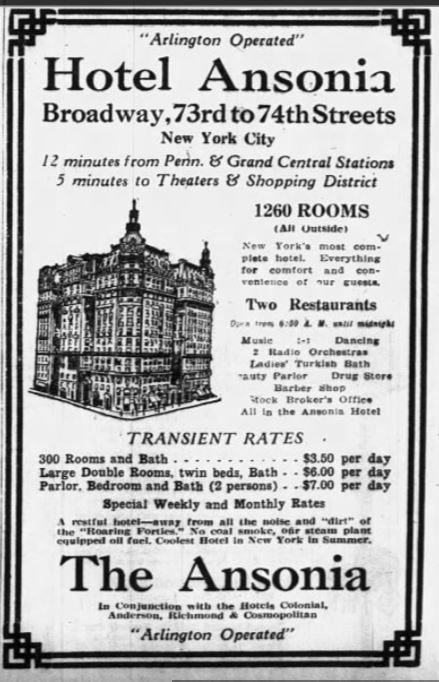

Erected between 1899 and 1903, on what was then still considered pioneer country at Broadway and Seventy-Third Street, the $6 million (give or take a million) Ansonia Hotel spared no expense. The luxury eighteen-story residential hotel included all the latest amenities–and then some.

The steel-frame structure featured air conditioning (in the form of frozen brine pumped through flues hidden in the walls), pneumatic tubing for sending and receiving messages, Turkish baths for women, the world’s largest swimming pool in the basement, and full suites equipped with electric stoves and freezers.

Oh yeah, there were also goldfish in a metal tank in the dining room, live baby seals in the lobby fountain, a farm with chickens and other animals on the roof, large elevators that could (and did) accommodate the residents’ horses, and a black cat that haunted the 16th floor.

The Ansonia’s Farm in the Sky

Much has been written about the Ansonia rooftop farm, but I’ll give a quick synopsis before I tell a more obscure story about the ghost cat.

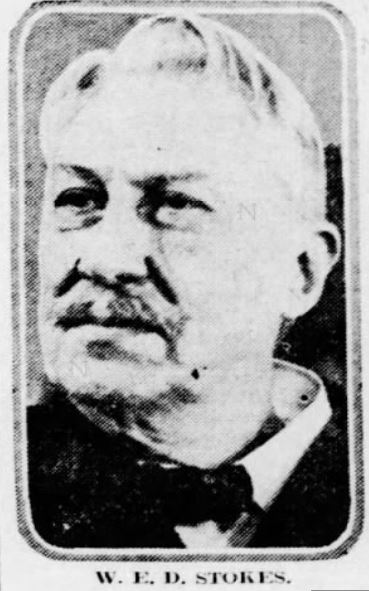

The Ansonia was constructed for William Earle Dodge Stokes, a multimillionaire New Yorker who was responsible for developing much of the city’s Upper West Side in the late 1800s and early 1900s. For his Ansonia Hotel, Stokes had a vision to create not only “the most perfectly equipped house in the world,” but also a self-sufficient building.

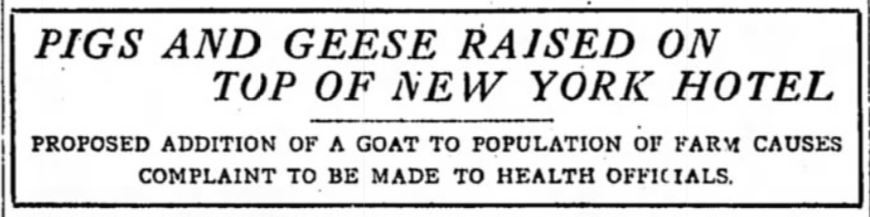

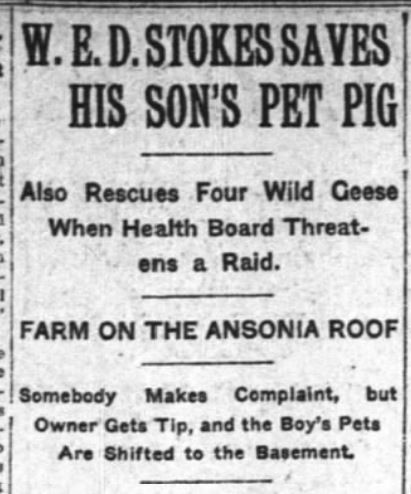

As part of this vision, Stokes incorporated a rooftop farm, which housed as many as 500 chickens, numerous ducks, at least one pig, and a small bear. Stokes called it “Birdseye View Farm.”

According to several reports, Stokes said he got the idea for the farm after he and his son, William Earle Dodge Stokes, Jr. (aka Weddie), had stopped at a farmhouse while “motoring” on Long Island. Weddie was immediately taken by a baby pig who had lost its mother, so they brought the pig back to the Ansonia and fed him for weeks with bottled milk.

Shortly thereafter, Stokes returned to the same farmhouse to purchase some geese to keep the baby piglet company on the hotel roof. They reportedly named the pig Nanki-Poo; the newspapers called the geese “Pa Gander and his wives.”

“Everything was quite sanitary, and the boy had great fun playing with his pets,” Stokes told a reporter. I’m not sure it was all that fun for the animals, though.

Although there were some artificial ponds on the roof, the roof had many obstacles, including a small home for the superintendent (who also served as head farmer) as well as machine shops and storerooms, skylights, and chimneys. The pig reportedly spent a lot of time digging up the fire bricks, and the geese spent much of their time flying over the parapet and getting lost in neighboring yards.

Sometime after he had acquired the pig and the geese, Stokes added chickens and a chicken coop to the rooftop farm. For a short while, a bellhop delivered fresh eggs to all the tenants; any surplus was sold to the public.

The farm was short-lived, thanks in part to a few residents who started filing complaints with the Health Department after hearing some rumors that Stokes was going to add a goat and a cow to the sky-top menagerie.

In November 1907, Stokes learned that the Health Department was planning to raid his farm. He and Weddie went up to the roof in the twilight hours and removed all the animals to the basement by way of the large freight elevators. When the inspector arrived the next day, Stokes was very courteous and more than happy to show him the empty roof (I have no idea what he did with the chicken coops and artificial ponds).

According to The New York Times on November 12, 1907, Russel Raynor, who directed the investigation, wrote, “My Inspector reports that Mr. Stokes has been misrepresented, and that there was no violation of the Sanitary Code. There were no animals on the Ansonia roof.”

I’m thinking someone’s palms were greased, but that’s just my opinion.

Most of the farm animals were reportedly sent to the Central Park Menagerie. However, Stokes apparently held onto some of the chickens: According to an article detailing W.E.D. and Helen Stokes’ divorce proceedings in April 1921, Stokes kept 45 chickens in their kitchen at the Ansonia, “and the apartment was so ‘filthy’ she could not eat there.”

According to news reports, pets were eventually allowed in the building through at least 1930: In 1926, a Boston bull terrier alerted guests to a fire in the building, which sent all the residents and their pets fleeing the hotel. Another fire in December 1930 also sent guests into the street with their pet dogs and birds.

The Ansonia Hotel Ghost Cat

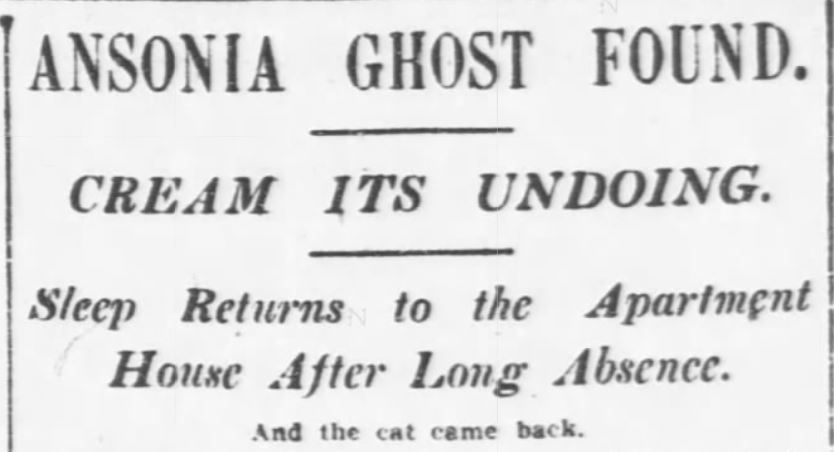

In 1903, a black cat started rapping on the door of Mrs. John Edward Smith, who lived on the 16th floor of the Ansonia. Discarding the rules of the house against pets (apparently the rules were changed later on), Mr. and Mrs. Smith welcomed the cat into their home and cared for it.

Opposite their door was the suite of rooms occupied by Louis Eugene Jallade, an architect who worked on the construction of the Ansonia. When he learned of the cat’s presence, he bypassed hotel manager Guernsey E. Webb and instead ordered Thomas Gill, a hall boy, to put the cat in a box and dump it along Riverside Drive and 85th Street.

Gill apparently complied, but the box slid out of his hands and rolled down an embankment, landing on the New York Central Railroad tracks. Gill said he thought he had heard a plaintive meow when the box landed, but he wasn’t certain. In any event, the cat came back. Can you blame him?

The next day, the tenants could hear plaintive cries and clawings throughout the building. Many of the cries appeared to be coming from the hollows that were carved out of the walls for the wires, cooling system, and messaging tubes.

Some tenants thought the Ansonia had its own ghost. Over the next few days, management received complaints from the Scotts on the 10th floor, the Carpenters on the 15th, Miss Boyer on the 16th, and many others.

A search party consisting of all the clerks on duty went hunting for the ghost on each of the 17 floors, but they came up empty. By this point, even Stokes started to believe that his building was infested by spirits.

New York Public Library Digital Collections

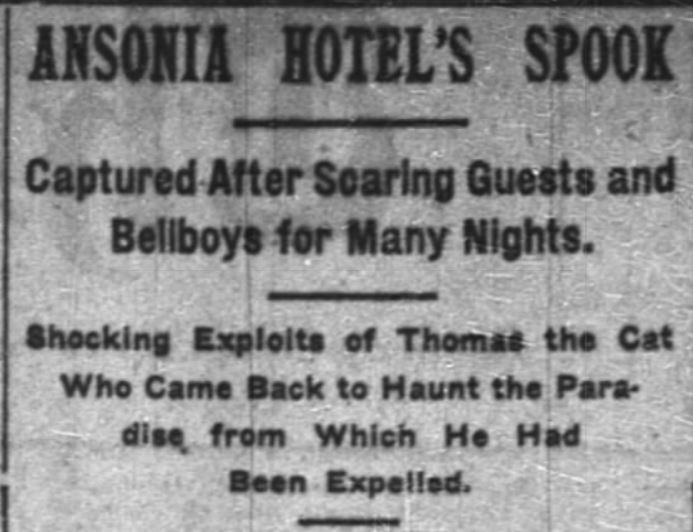

According to articles in the New York Tribune and New York Times, Theodore Gordon, the leader of the orchestra for the main dining room on the first floor, was reportedly putting away his violin when the cat reached for his legs. The cat, which everyone started calling Thomas, clawed his way up Gordon’s back, which sent Gordon screaming down a flight of stairs.

Thomas eluded all attempts to capture him. He ran up to the fourth floor and jumped into an opening leading to a ventilation shaft. From there, somehow, he made his way into a ceiling alcove in Jallade’s apartment.

A carpenter was called in to cut out a two-foot section of the “beautiful wall” in a room facing 74th Street in which he placed a bowl of cream. A wire noose was then fixed over the bowl.

Hungry Thomas made his way to the cream, allowing the men to grab him and put him in a champagne basket. The poor kitty was delivered to the West 68th Street police station with a special request to send him to the Bergh Society (ASPCA). The police refused to keep the cat overnight, so Thomas was allowed to spend one more night in the Ansonia basement inside his basket (that was a big risk).

Sadly, Thomas’ days of living in luxury came to an end courtesy, once again, of the SPCA. As the New York Times noted, “A satisfying breakfast and a sudden death after it await the Ansonia Hotel’s “spook” when he wakes up this morning. Having been an unsolved mystery for ten days, causing sleepless nights to the hotel’s guests and frightening the bellboys so that they threatened to resign, he will meet an ignominious end at the hands of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.”

I’d love to think that the cat’s ghost is still roaming the halls of the Ansonia building today (or that somewhere over the rainbow bridge, there is a cat dreaming about his adventures at the beautiful hotel)!

My Wife’s Lovers, 1891, Oil on canvas. Collection of John and Heather Mozart.

John Broome and His Chevilly Estate

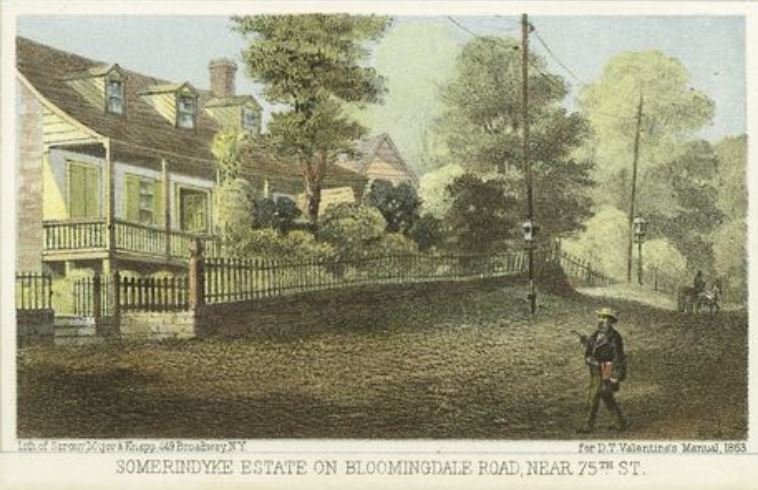

The following is a brief history of the Ansonia Hotel and surrounding lands, for those of you who would like to step back in time and take a carriage ride up the old Bloomingdale Road (Broadway) to the Upper West Side…

The Ansonia Hotel was constructed on the northwest corner of Broadway and West 73rd Street, on what was once a 16-acre farm along the Bloomingdale Road between 71st and 73rd Streets. During the early 1800s, the farm was owned by Revolutionary War veteran John Broome, who called his property Chevilly.

The recorded ownership of this property goes back to Anthony John Evertsee, a freed slave who acquired a grant for the farm in the 1600s. Evertsee conveyed the land to Jacob Halsted on March 23, 1697. About 100 years later, in 1801, Broome purchased the farm from George Dyckman for $18,000.

The property included a large house in “the French style” located smack in the middle of today’s 72nd Street just west of Broadway. Although some reports state that Madame d’Auliffe (Marie Antoinette’s maid-of-honor) built the home after fleeing France during the French Revolution, other historical accounts show that it was Nicholas Olive, a wealthy French merchant, who had first lived there with his wife. The confusion could be due to the fact that the French pronunciation of Olive (oh-leev) is similar to the American pronunciation of Auliffe (oh-leef).

An ad in the Evening Post in January 1811 described the home at Chevilly as being 80 x 36 feet, with piazzas in the front and rear. It had 14 rooms, 10 of which had fireplaces. The home featured a “good cellar” comprising a kitchen, fruit cellar, etc. On the premises were also a two-story house occupied by the gardener, large stables and coach houses, a wash house, ice house, cow house, hay barrack and poultry house, and yard. (Kind of sounds like the Ansonia Hotel rooftop!)

“There are two large gardens excelled perhaps by none on the Island, and a choice collection of dwarf and other fruit trees, mostly imported from Europe. The grounds are laid out and ornamented with a variety of trees and shrubbery in a style of superior taste and beauty, rendering this one of the most elegant and desirable seats in the vicinity of New York.”

According to the ad, the main house, out houses, and gardens occupied about one third of the acreage. The land was on a bank that gradually rose from the river to a commanding height, offering extensive views up and down the Hudson River. The outskirts of the property were “handsomely wooded.”

Following Broome’s death in 1810, the history of the property is a bit shady–I found varying accounts of what happened to it. One account says that the property was sold and then later acquired by James Boggs, the husband of Sarah Lloyd Broome, who purchased the land in 1821 from Joseph Simpson for $8,000. This account states that Boggs and his family used it as a country home until about 1830 (when they placed an ad to lease the property).

Sticking to this story, following James’ death in 1834, the property, including carriages and cattle, was left to Sarah. James’ will reportedly stipulated that Sarah and their heirs hold onto Chevilly for as long as possible until the land was at prime market value.

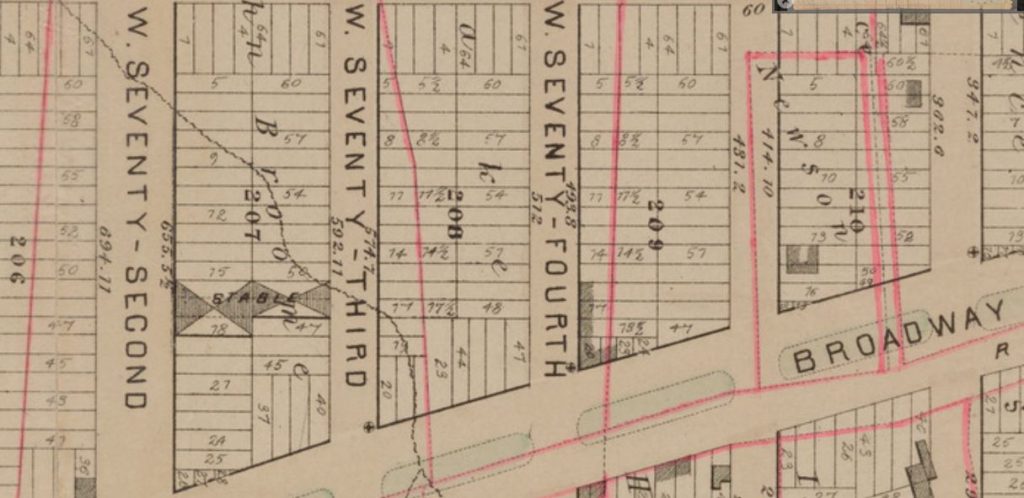

The heirs did retain the property until April 1, 1867, when Mary R. LeRoy sold it to Gustavus A. Sacchi for $400,000. The purchase included 200 lots. One year later, the upper portion of Broadway was opened, paving the way for future development, which would come about 20 years later.

During its last decades of life, the old Chevilly home was occupied by John Lozier, Alderman for the Sixth Ward, and later, certain well-known bachelors such as August Belmont and Frederick S. Talcott used it as a club house and driving resort.

W.E.D. Stokes and the Building Boom

According to an article in The New York Times in March 1886, the greatest building activity in Manhattan at that time took place in the area bounded by 70th and 95th Streets between 8th and 11th Avenues. The article noted that this area was still vacant land scattered with “a few dilapidated relics of the splendor of bygone generations.”

The article continued, “The once proud estates of Somerindyke, Peletiah Perit, Fernando Wood, Harsen, and James Boggs have been split into blocks and the blocks divided into lots, each of which now commands a price as great almost as the original cost of any one of the old estates…Among the pioneers of the recent boom were F.M. Jenckes, William E. Dodge Stokes, and Jacob Lawson.”

Also in 1886, John Jacob Astor purchased part of the old Broome land bounded by present-day 72nd and 74th Streets, Riverside Drive, and West End Avenue.

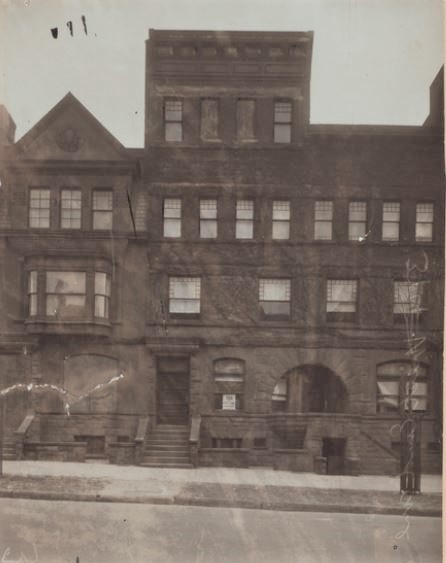

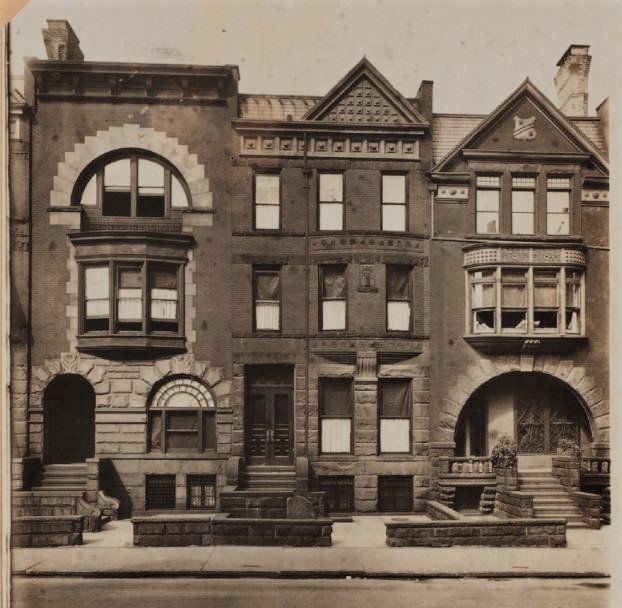

It was during this time that Stokes quietly began purchasing 22 parcels of land on the site of the old New York Orphan Asylum, bounded by 73rd and 74th Streets and the Boulevard (Riverside Drive) and 11th Avenue (West End Avenue). In 1886 he constructed 19 homes on West 74th Street (some of these old brick homes are still standing). He also had a block of “10 elegant dwellings” (three- and four-story brick homes) on West End Avenue between 74th and 75th Streets.

He filed the plans for the Ansonia Hotel in January 1898. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Broome constructed these homes at 249-253 West 74th Street near West End Avenue (pictured here about 1912). Broome’s homes were described as “architectural novelties,” each having its own distinctive appearance.

For those of you who are interested in learning about the seedier side of W.E.D. Stokes (let’s just say he may have been the Jeffrey Epstein of his day), and of the scandals that rocked the Ansonia (orgies, abortions, adultery, gambling, pornography, etc.) please feel free to check out New York Magazine’s The Building of the Upper West Side. I’ll just leave it at that.