We return to Brooklyn–just about 20 blocks east of the “lacteal orgy” that occurred 14 years earlier in Bedford–for another delightful cat tale that took place on Halloween on Pitkin Avenue in Brownsville. No tricks, only some treats (including some interesting facts about how Pitkin Avenue came about–a group of “Wheelmen” get most of the credit).

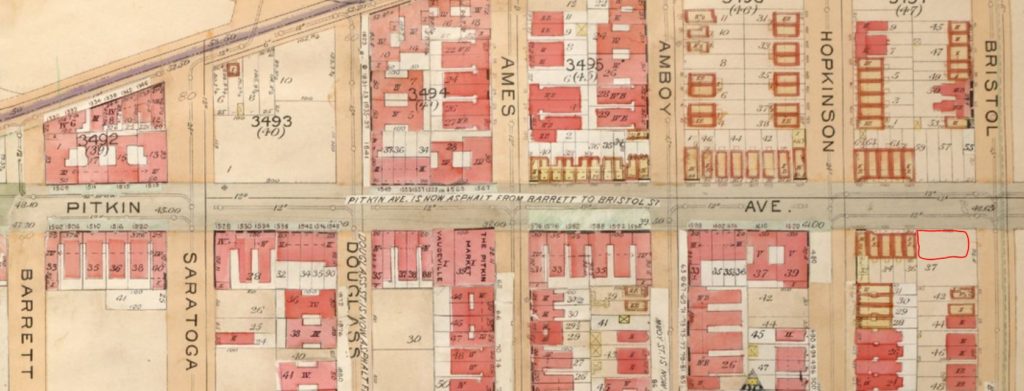

On Halloween Day, 1921, a fire broke out in the Holland Millinery Shop at 1636 Pitkin Avenue in Brownsville, Brooklyn. According to news reports, the fire was the result of a gas explosion.

Engine Company No. 233, Engine Company No. 283, and Truck No. 123 were three of the many fire companies that responded to the three-alarm fire. While the firemen rushed into the building, police officers ordered everyone to evacuate the row of tenement houses across the street. Reserve police officers from the nearby Brownsville police station were also called in to hold back the crowd.

One of the firemen who entered the building was Walter Smith of Engine Company No. 233 (aka, the Fightin’ 33rd). He was working on the second floor when he felt something persistently rubbing against his foot. The smoke was too thick to see, so he bent down to feel what was rubbing him.

To Smith’s surprise, it was a cat with a box of four kittens. Apparently, she had dragged the box away from the flames, but she could not get the box down the stairs without spilling its precious contents. Somehow she knew to get the fireman’s attention.

Fireman Smith rescued the mother cat and her four kittens. He was badly injured in the fire (he was cut by falling glass), as were firemen Ernest Withers and Henry Cooper, who were both overcome by gas fumes. There was no further news on the cat and her kittens, so hopefully they all survived.

The fire–which was later determined to be an act of arson–destroyed all the buildings from 1632 to 1640 Pitkin Avenue, which, in addition to the hat shop, included the Keene Furniture Store, Sachs Furniture Company, Parkway Bakery and Lunchroom, Tolk Business School, and a commercial branch of the telephone company. Damage was estimated at $100,000.

A Brief History of Pitkin Avenue

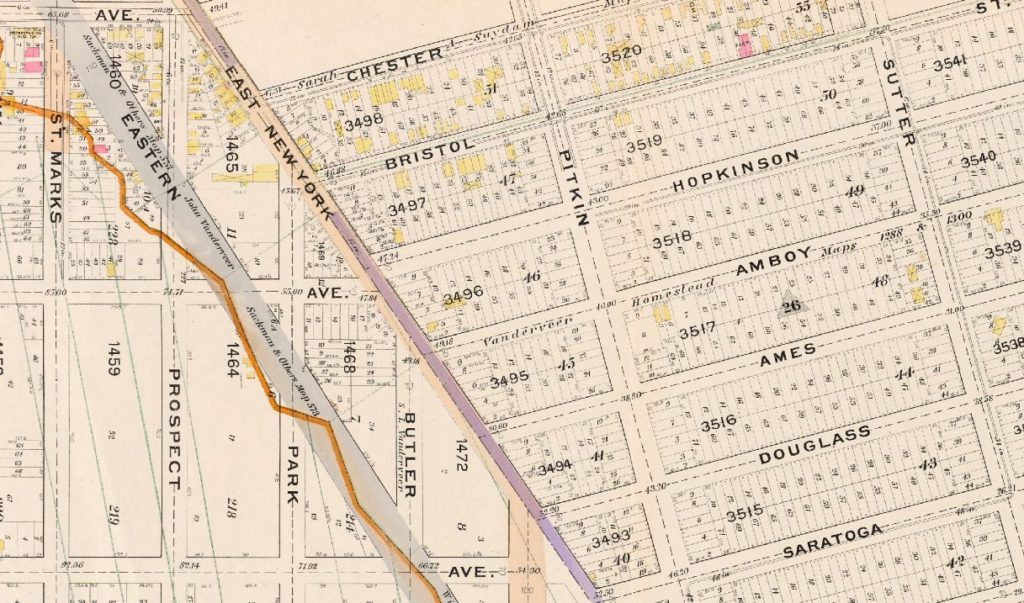

Pitkin Avenue is named for John R. Pitkin, a New England merchant and real estate speculator who came to the town of New Lots (formerly New Lotts of Midwout, then New Lotts of Flatbush) in 1835. His plan was to construct a ship canal extending from Jamaica Bay to New Lots on the Brooklyn-Queens County border; Pitkin believed this new port of entry would be a rival to New York City.

Pitkin and his real estate partner–his brother-in-law, George W. Thrall–purchased the Wyckoff, Stoothoff, and Van Sindern farms near the old William Howard estate, which was located on the old King’s Highway (right about where present-day Broadway meets Fulton Street, near the Alabama Avenue train station).

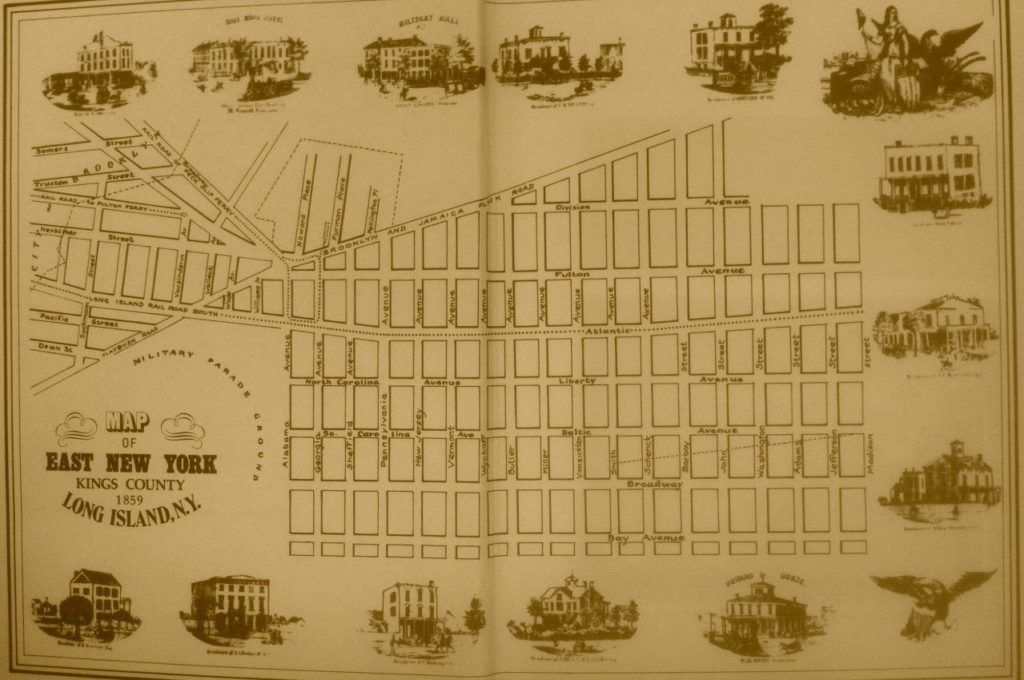

Pitkin and Thrall had the land surveyed and laid out streets and building lots, which were sold for $10 to $25 each. The men named their new development the Village of East New York, claiming it would become the eastern part of New York City.

To help attract buyers, Pitkin published maps and a prospectus. He also published the area’s first newspaper, The Mechanic (the office for the newspaper was located in a three-story stone building at the corner of Atlantic and Pennsylvania Avenues).

Pitkin also set up a shoe factory on Liberty Avenue, called the East New York Boot and Shoe Manufactory Company of New York. His workmen (the company employed about 100 people) constructed small cottages around the shop in the area of Pennsylvania and New York Avenues.

The dream didn’t last long. The Panic of 1837 forced Pitkin to shut down his shop and either return some of the land to its original owners or sell it at reduced prices. Pitkin retained a small section between Wyckoff (today’s Wyona Street) and Alabama Avenues, which is where his businesses had been located.

One of the men who purchased property in the new village was William H. Suydam, who was a justice of the peace of Kings County. In 1858, he parceled his 30-acre property into 262 lots (a map of which was filed in 1860), and provided simple two- to four-room homes for workers living in the area.

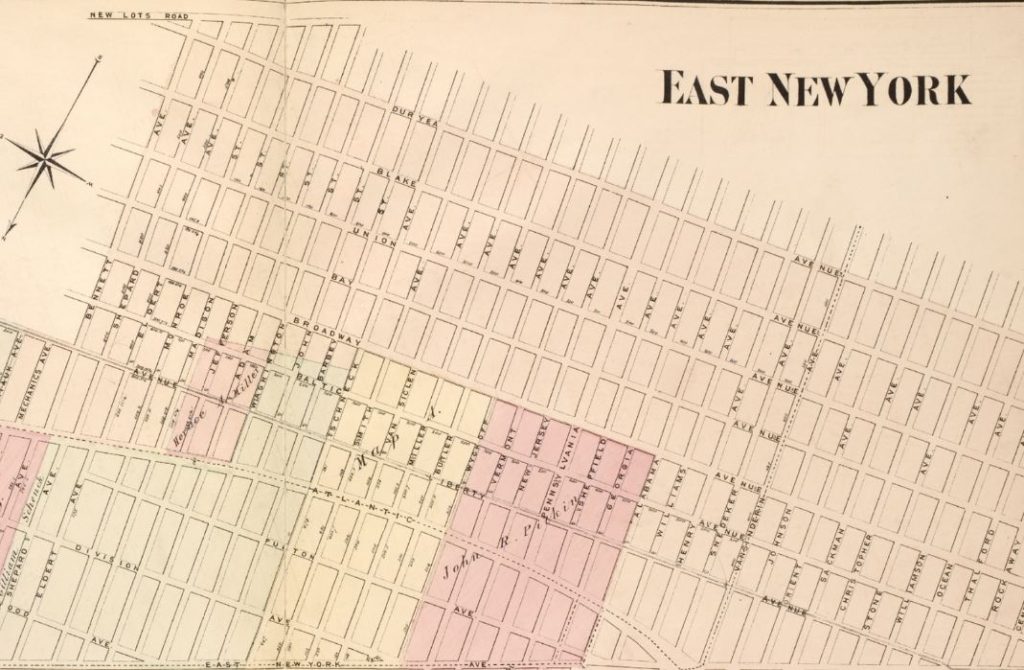

When Suydam ran out of funding and failed to pay his mortgages, his land was auctioned off to Charles S. Brown of Esopus, New York, who paid $12,000 for the property. Brown subdivided this land and an adjoining parcel and marketed the $50 lots to Jews who lived in the congested tenements of the Lower East Side. He set up two rows of houses in the fields just west of Manhattan Crossing (today’s Broadway Junction, bounded by Fulton Street, Eastern Parkway, and Broadway).

By 1883, there were about 250 cottages in Brownsville (or Brown’s Village), most of them constructed by Charles R. Miller to accommodate factory workers who continued to work in Manhattan. The community, which also had a few shops, was surrounded by meadows and a dairy farm. At this time, the unpaved Pitkin Avenue (Broadway) served as a significant commercial thoroughfare for supplying the working-class residents with meat and vegetables, clothing, furniture, and more.

Pitkin Avenue: A Good Road for Wheelmen

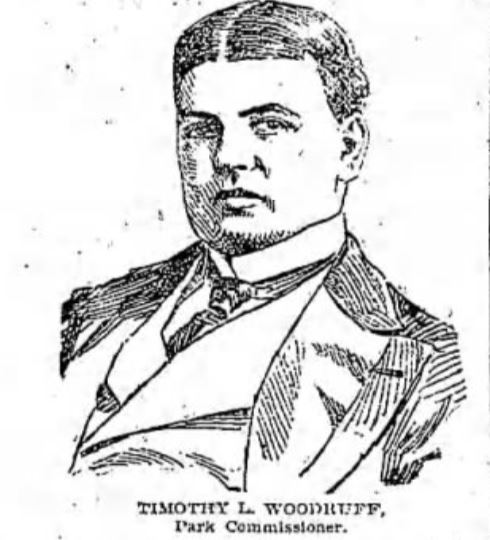

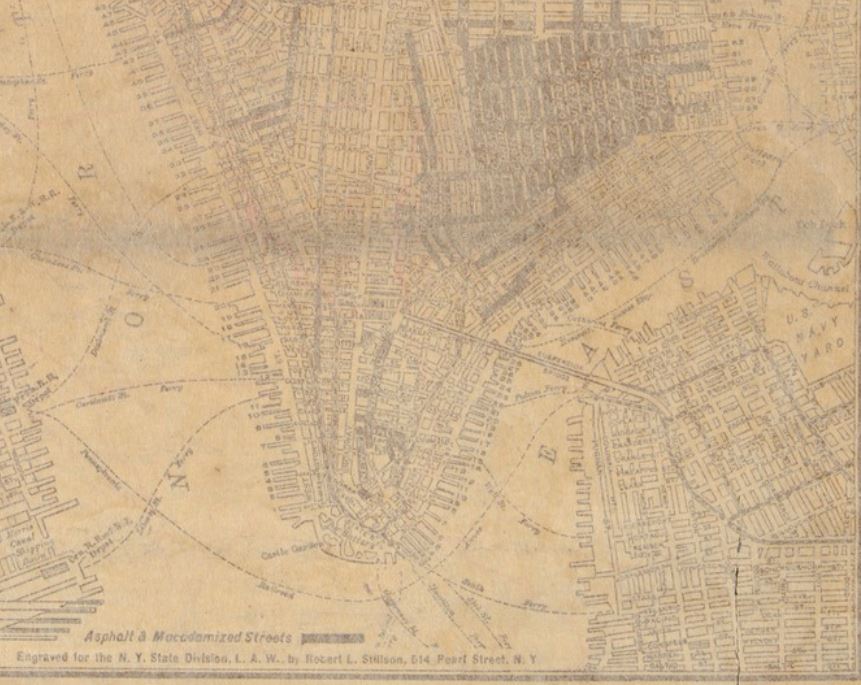

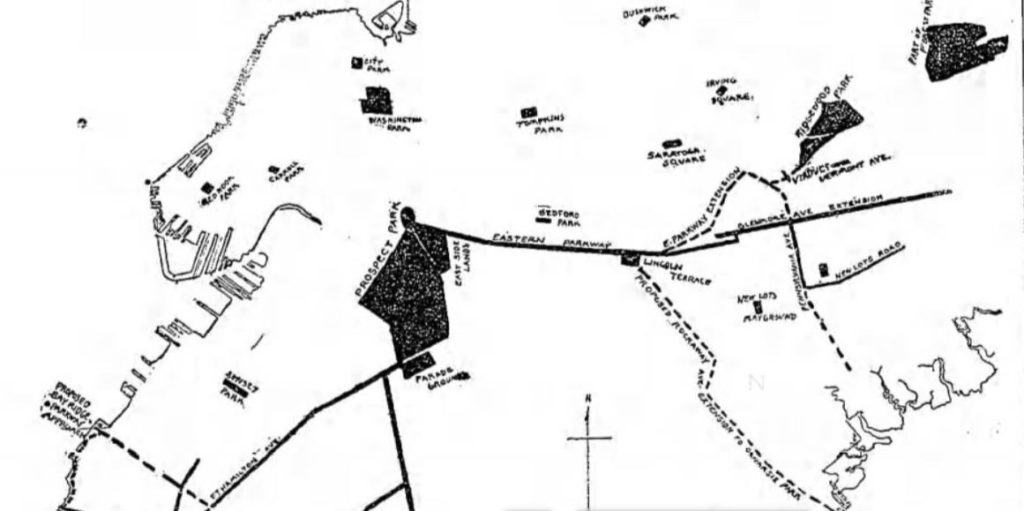

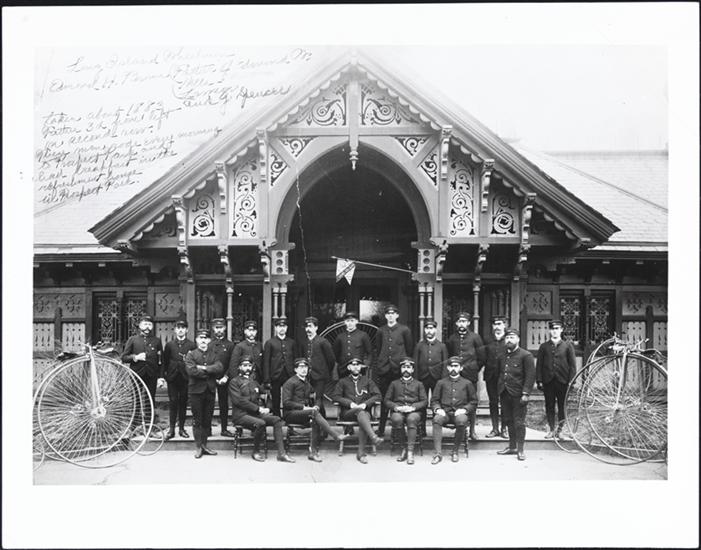

In the mid 1890s, several “Wheelmen” from the many New York bicycle clubs proposed creating a system of cycle roadways dedicated to the cyclists who wanted to traverse Brooklyn on safe roads. The proposal led to the creation of the Good Roads Association of Brooklyn. The group was championed by Brooklyn Park Commissioner Timothy L. Woodruff, who was also an avid cyclist.

At this time, the Eastern Parkway ended abruptly at a hill at the Brooklyn city line near Ralph Avenue, making the descent to the continuing dirt road (Broadway) treacherous for cyclists who wanted to ride toward East New York or Queens County. The men originally proposed improving Glenmore Avenue, since a part of that roadway had already been paved, but it was then decided to improve Eastern Parkway from Ralph Avenue to Stone Avenue.

In addition to extending the Eastern Parkway northwest to Ridgewood Park (then home to the Brooklyn Bridegrooms baseball team, now called Highland Park), the plan was to macadamize the road from Howard Avenue to Stone Avenue (now Mother Gaston Boulevard). Thus, the old Broadway became an extension of the Eastern Parkway.

At Stone Avenue, the cycle path would head north one block to Glenmore Avenue, which was also being extended. The path then headed east again on Glenmore to Endsfield Avenue (Eldert Lane); then along Liberty Avenue into Queens County.

The first part of the new cycle path system was celebrated with a grand parade on June 27, 1896, organized by the Good Roads Association, with Park Commissioner Woodruff as Grand Marshall. The New York Times reported that at least 10,000 Wheelmen and Bloomer Girls and 100,000 spectators took part in the celebration.

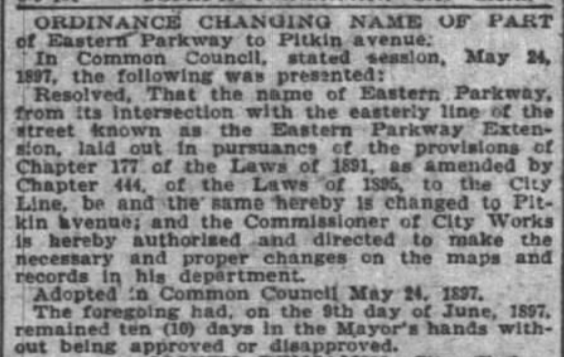

In May 1897, the City Council passed an ordinance changing the name of the newly extended portion of Eastern Parkway to Pitkin Avenue. Under this ordinance, the street was widened from 50 feet to about 82 feet.

The widening of the road created quite a stir, as only some residents were paid well for their property when the city took it over, while others were told the money appropriated for this purpose had run out.

October 25, 1898

Some residents along Pitkin Avenue–including those with property near Bristol and Chester Streets, where the cat saved her kittens in 1921–fenced off the sidewalks in front of their house in protest. This forced pedestrians to share the macadamized roadway with the “hundreds of cyclists” who were “passing continually.”

The city suggested that these residents should simply be happy to “donate” their land to the city in exchange for the improvements made to the old dirt road.