Warning to my readers: This story about a tragic event at New York City’s SPCA Shelter for Animals is not a happy one. It is, in fact, incredibly disturbing. And it was very hard to write.

It involves injury and cruelty and death–both human and feline. But it is an important story to tell, because it is part of mankind’s history. It is also a major part of the ASPCA’s 150-year history in New York.

This sad tale opens our eyes to the historical treatment of animals, and shows us how much progress we’ve made when it comes to treating cats, dogs, and all animals with dignity and compassion. We still have a long way to go, especially when it comes to ensuring that every shelter is a no-kill shelter. We cannot let this history ever repeat itself.

The Fatal Explosion at the SPCA Shelter

Can electric sparks from cats’ fur cause a gas tank to explode? That was the question on everyone’s minds when a gas tank exploded in a steel “dispatch” at New York City’s SPCA Shelter for Animals on November 12, 1903.

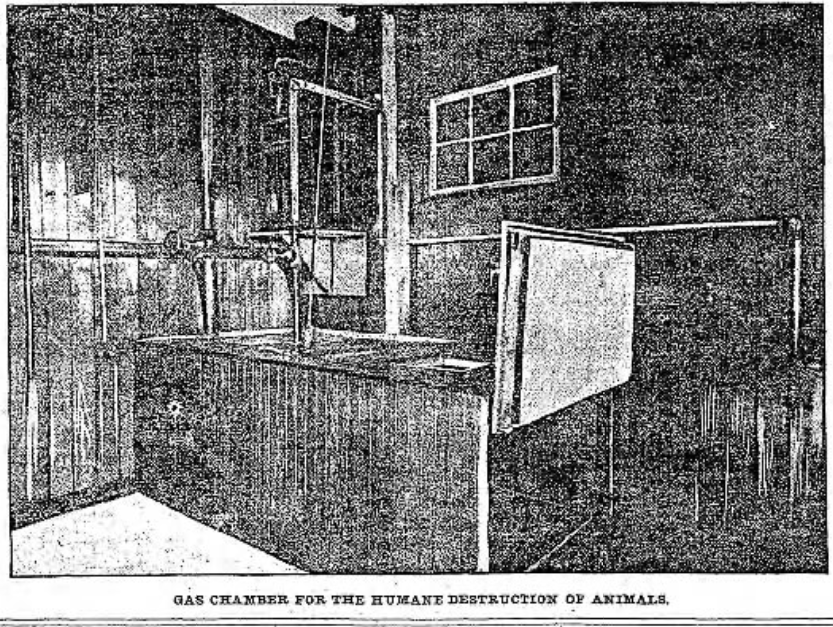

The dispatch was a euphemism for gas chamber. Basically, it was a steel case, about ten feet long, four feet wide, and four feet high, that was used daily for asphyxiating thousands of stray cats and dogs during the 1890s and 1900s. (In 1902, for example, almost 28,000 dogs and 64,000 cats were “humanely” destroyed by the SPCA.)

The case was charged with gas mixed with air from the street gas main; it was freshly charged before each execution. The men who worked at the shelter called it the “happy dispatch” because unlike killing via drowning or beating (which was used on stray dogs from 1855-1895), the gas reportedly put the animals out of their misery “as quickly as possible.”

On this particularly miserable day, the tank already held about a dozen poor critters when cat wagon driver Theodore Goodenough of 340 West 15th Street arrived at the animal shelter at the foot of East 102nd Street. He had just completed his daily roundup of stray cats, and his wagon was full of felines in wicker baskets.

Working with Andrew Schofield of 411 West 50th Street and Charles Schoenfield of 2344 First Avenue, Goodenough “dumped three basketfuls” into the tank as the other men held up two covers made of heavy plate glass set in steel frames.

When he got to the fourth basket, a black Tom cat dug his claws into the wicker basket, pinning two other cats against the side of the basket with him. Goodenough pushed the basket farther into the tank and shook it until all of the cats were released.

As the three men started to leave the room, there was a flash and a bang “and a shower of cats.” People working in the office ran in to find Goodenough, Schofield, and Schoenfield stretched across the floor among a pile of “fur and fragmentary cats.” The explosion not only destroyed the steel tank, but it also blew a hole through the ceiling.

Outside, the horses ran off with the cat wagon, which was still filled with several baskets of unwanted and unloved street cats. About two dozen dogs in the shelter awaiting their rescue or death started howling in response to the ruckus. An ambulance came and took the three injured men to Harlem Hospital.

Goodenough fractured his skull, and was not expected to survive. Schofield suffered from burned and lacerated hands, and Schoenfield sustained injuries to his hands and face.

During an inquiry, the men and manager John Reid said that no one had been smoking in the room (anyone caught smoking in the building would have lost his job), and there were no lights of any kind burning. The only explanation they could give was the suggestion that the cats’ fur emitted sparks when they were rubbing against each other in their efforts to survive.

A few reporters said this theory could have been feasible. Just recently, they noted, a woman had created a spark by walking over a Brussels carpet, which in turn set fire to her hair as she was drying it.

Another Shelter Explosion

Sadly, history did repeat itself in December 1908. This time, an explosion in the tank killed about a dozen dogs and severely injured Hugh Dunlevy, who was in charge of it. The explosion also wrecked the shed where it was located at this time (apparently they moved the tank out of the main building following the explosion in 1903).

Dunlevy was taken to Harlem Hospital for treatment of burns to his head, arms, and hands. He could not tell what caused the explosion.

A Brief History of the SPCA

The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was founded in England on June 16, 1824.

Although the founders were originally mocked and scorned for their efforts to “ask for justice to the lower creatures of God,” they eventually earned the respect of many distinguished members of both Houses of Parliament. In 1840, Queen Victoria honored the society with the prefix of “Royal.”

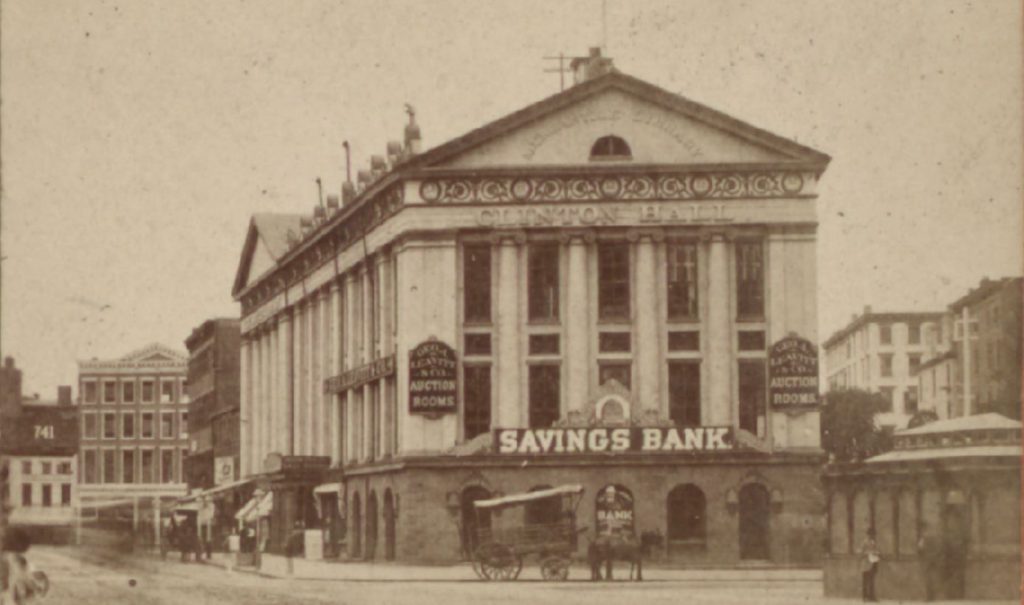

It was while Henry Bergh was serving in London under the Lincoln administration that he made the acquaintance of John Colam, Secretary of the Royal SPCA. Finding no similar society in America, Bergh delivered a powerful lecture in Clinton Hall on February 8, 1866, in which he plead his case to establish an SPCA in the United States.

Three months later, on April 10, 1866, the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was incorporated by the Legislature of the State of New York. Nine days later, New York passed its first law making it illegal (misdemeanor) to “neglect, maliciously kill, maim, wound, inure, torture, or cruelly beat any horse, mule, cow, cattle, sheep, or other animal, belonging to himself or another.”

In 1894, the city replaced its horrific and abusive system of dog catching and impounding with new legislation that abolished the city dog pound and empowered the SPCA to carry out the duties of animal control. The bill became law on March 8, 1894; the Society immediately erected its Shelter for Animals on East 102nd Street.

According to the 43rd Annual Report of the ASPCA published in 1908, the shelter was “provided with every accommodation for the care of animals and their humane destruction.”

In 1895, at the request of Mayor Frederick W. Wurster of Brooklyn, the law was amended to include that city as well (Brooklyn was not incorporated into the City of New York until 1898). A shelter was established in Brooklyn on the corner of Malbone Street and Nostrand Avenue.

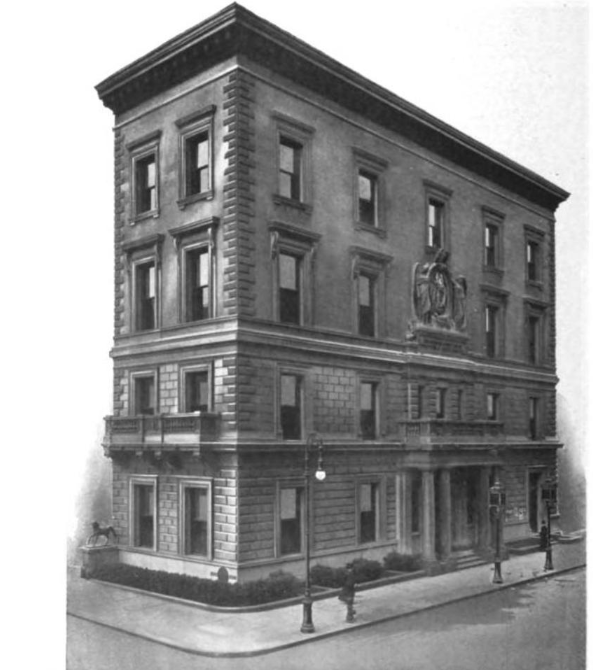

In 1896, the SPCA secured new headquarters in a fireproof building at 50 Madison Avenue, on the northwest corner at 26th Street. And in 1898, the SPCA opened another shelter on Wave Street in the Stapleton section of Richmond (Staten Island).

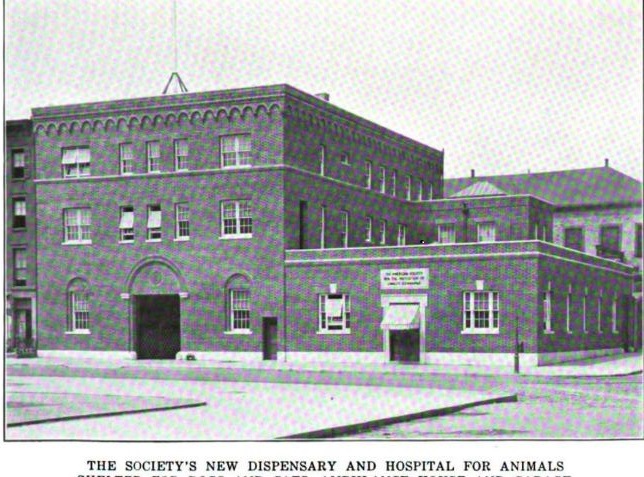

In 1912, the SPCA opened a modern free dispensary and hospital for animals at Avenue A and 24th Street, “equipped with every known appliance for the care and treatment of diseased and injured animals.”

The new facility had a one-story shelter that replaced the old one on 102nd Street, and a three-story structure that comprised an ambulance house (formerly at 111 East 22nd Street) and garage on the ground floor; a dispensary and hospital on the second floor; and an isolation ward for horses, lockers and showers for employees, feed and hay loft, storage room, janitor’s quarters, and a machine shop on the third floor.

At this same time, a receiving station for animals was opened near the Madison Avenue Bridge at 135th Street to accommodate residents of Harlem and the Bronx.

Incidentally, last weekend my husband and I went to the annual New York Cat Film Festival. We had two hours to kill before the show, so we walked down 24th Street to the East River.

When we reached the Asser Levy Recreation Center, something pulled at me, and I left my husband on 24th Street to explore the area. I had a feeling that something with animals in New York history had happened on this site. I did not know until yesterday that I had been standing on the former site of the SPCA Dispensary and Hospital for Animals.