Cats in the Mews: February 8, 1889

I recently wrote about a cat that saved 150 lives in a building in Harlem in 1897. In this tale of Old New York, which took place when a gas leak endangered the lives of every resident in a four-story brick tenement building on East 75th Street, we meet two feline heroes and their canine sidekick. For those interested in history, this story also includes a brief history of Con Edison and New York City’s other gas companies.

The building at 241 East 75th Street was owned by William Sartorius, who occupied the entire ground floor with his wife and two sons. Thirty-three other people lived in the building, each family occupying about 800 square feet of space. I’m sharing the following details to provide insight into tenement life, and also because many of my readers have discovered their ancestors in my stories.

*William May, a locksmith, leased three front rooms in the basement. He used one room for his workshop and lived in the other two rooms with his wife, their 17-year-old daughter, Mary, and two teenage sons. The family also had a black foxhound and two cats who slept in the sub-cellar.

*Frederick Souter, the janitor, occupied the three rear rooms in the basement with his wife and four children.

*The large families of John Weisner and Henry Heidler (2 parents and five children each) lived in the two 3-room apartments on the second floor.

*James Rogan, a 28-year-old tinsmith, lived in the rear rooms on the top floor with his wife, Mary, her sister, Alice, and three young children. Ernst Swingman and his wife occupied the front rooms. The third floor was vacant.

The Gas Leak

On the night of February 8, a pipe from the Consolidated Gas Company’s main line on 75th Street sprung a gas leak, sending the product into the sub-cellar of the building. The gas was used for lighting fixtures in the hallways only; it was not used at this time for cooking, heating, or lighting fixtures inside the apartments.

As the gas rapidly filled the cellar and made its way up into the basement and other floors above, all of the tenants remained sound asleep. At about 4 a.m., Mrs. May woke up and covered the kitchen sink opening with a cloth, thinking the foul odor she smelled was sewer gas. She went back to bed.

About an hour later, the May’s two cats began howling in the cellar. The loud duet woke up Mary, who asked her mother what she thought was wrong with the cats. Mrs. May said the cats were probably just sick. She then got out of bed and started preparing breakfast for the family.

Mary thought the cats were dying, so she got up to investigate.

Upon opening the door to the cellar, Mary was overcome by the gas and nearly suffocated. Her mother did not notice that Mary was in trouble until the family dog joined the cats and started howling.

Feeling woozy herself, Mrs. May woke up her husband, who in turn made a frantic attempt to wake up his 15-year-old son, Anthony. Their other son, William, staggered out of his room and fell to the floor.

Hearing the human and animal cries of alarm, Mr. Sartorius and Mr. Rogan ran down to the basement to help carry Mary and Anthony outside; William made it outside on his own. All three teens were brought to a neighborhood stable, where they soon recovered in the fresh cold air. Several men summoned the firemen at nearby Engine 44 for help.

Similar scenes took place upstairs, as several residents fell ill or passed out from the gas leak. Miraculously, all but Mrs. Rogan and her sister–who were taken to nearby Presbyterian Hospital–recovered quickly in the winter air.

By noon that day, the dog and cats had recovered and were as playful as ever. As The New York Times reported, “If it had not been for the noises they made, it is probable some fatalities would be recorded today.”

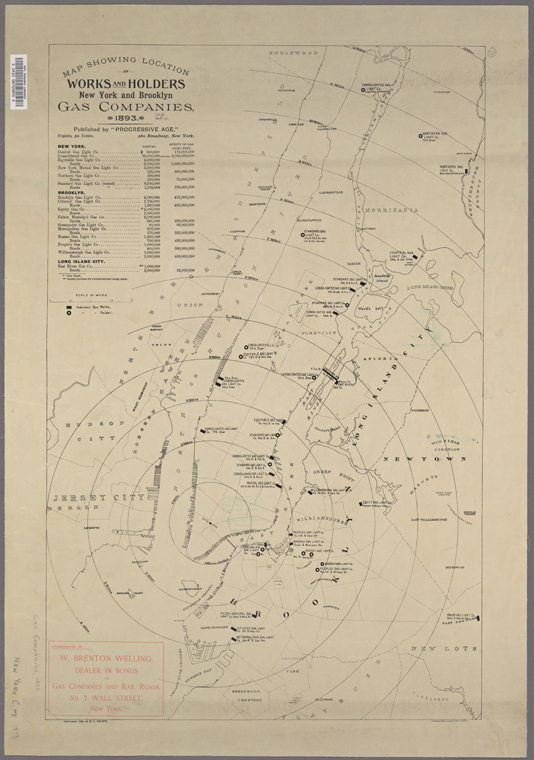

New York City’s Gas History

New York City’s gas history began in 1823, when the New York Gas Light Company became the state’s first manufactured gas company. Manufactured gas was a process that used various forms of wood resin (and later, coal) as opposed to natural gas.

The New York Gas Light Company received a charter from the New York State Legislature to provide gas-powered lighting from the Battery up to Grand Street. The company laid its cast-iron pipes, starting at Canal Street and Broadway, and focused on supplementing or replacing the whale-oil street lamps that had been installed starting in the 1760s (gas was not originally used for home lighting, cooking, or heating).

In 1833, a rival company that manufactured gas from coal entered the business (coal-based gas entailed combining crushed coal with steam at pressure, which produced dark smoke and noxious odors from the hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, and lime used in the process.) The Manhattan Gas Light Company’s franchise allowed it to service all of the island north of the Grand Street/Canal Street line.

The city continued to expand northward, paving the way for the Harlem Gas Light Company (1855), which serviced all territory north of 79th Street, and the Metropolitan Gas Light Company (1858), which set up shop from 34th Street up to 79th Street. (Metropolitan would have been the company that ran the gas lines along East 75th Street.)

By the late 1870s, Manhattan had six major gas companies, each of them battling for the right to lay pipe across a rapidly expanding city. In their efforts to grow their business, each company tore up the streets to install and repair their own gas mains, or to remove those of a rival company. They built multiple gas production works and holders (massive tanks) and laid large-diameter transfer lines to connect facilities throughout the city.

For the first 50 years or so, the gas light companies focused on street lights and other lighting fixtures. But this business plan took an abrupt turn after Thomas Edison launched the Edison Electric Light Company in 1878 to develop a system for powering lamps with electricity. The gas companies began promoting their product as a clean alternative to burning coal or wood, which made it ideal for residential heating and cooking (no more coal bins or ash cans).

With Edison on their heels, the only chance for survival was consolidation. So, on November 11, 1884, the New York, Manhattan, Metropolitan, Municipal, Knickerbocker and Harlem gas light companies merged to create the Consolidated Gas Companies of New York.

During the subway construction in the early 1900s, gas lines were rerouted, small service lines were laid along the curbs, and temporary wrought-iron bypass mains were suspended from scaffolding above the streets (the old cast-iron mains were turned off during construction). Although some of the older cast-iron pipes were replaced by new wrought-iron pipes, the wrought iron was no more immune to corrosion, deterioration, and leaking.

Natural Gas Comes to Manhattan

In 1951, the 30-inch, 1000-mile Transcontinental pipeline from Texas began supplying natural gas to five receiving gas utilities in Manhattan and Long Island.

Now, keep in mind that the original mains under the city’s streets carried manufactured gas produced from wood resin and bituminous coal. When the city switched over, the dry chemical composition of natural gas began drying out the seals in the joints of old iron pipes.

This decomposition has now been going on underground and out of sight for 70 years. Hence, the number of reported gas leaks continue to rise.

Today, natural gas provides 65% of the heat and hot water to New York City households. In the last decade, there have been more than 100,000 reported gas leaks, a few of them resulting in injuries and fatalities.

Following a 2014 gas explosion that killed eight people in East Harlem, Con Edison reportedly increased gas safety patrols surveying 4,300 miles of gas mains every month. The company also developed an online gas map that shows current leaks throughout the system. Recently, the map indicated about 500 leaks in the city, including 200 in Manhattan.

Sure, the gas companies put additives in natural gas to give it a distinct odor, but perhaps ConEd should also hire a few thousand cats and dogs to monitor these gas leaks and serve as alarms to ensure the safety of modern-day New Yorkers.