Cats in the Mews: February 19, 1893

On this day in 1893, a little five-year-old boy named Willie Morton did what many grown men and tender-hearted women had failed to do: He rescued a cat that had been stuck high in a maple tree at the corner of Court Street and First Place in the Carroll Gardens section of Brooklyn.

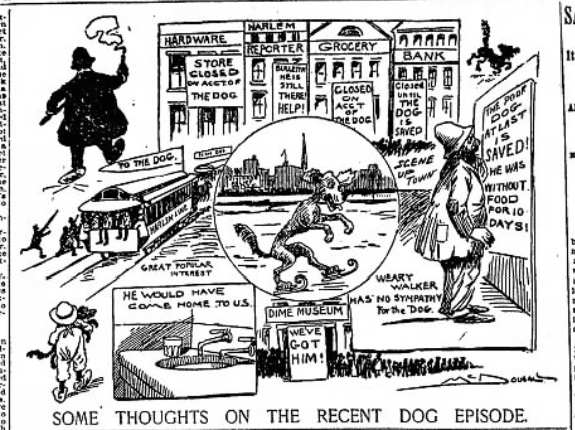

According to the New York Evening World, the poor cat had been stuck in the tree for five days, after escaping from a fierce bulldog. Despite the efforts of many grown men and the coaxing voices of many women, the cat refused to budge from his perch.

On Friday, some mean children and their parents just laughed at the cat as they passed by. But after a snowstorm that evening, these same people began crying, “Poor thing!”

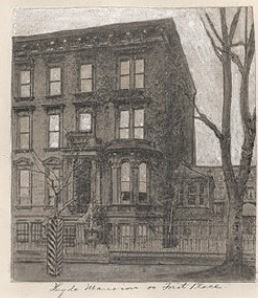

One known high-society member of Mrs. Caroline Astor’s Four Hundred who lived on First Place even shed tears for the kitty in distress. (Perhaps this man was Charles Carroll, a descendant of Charles Carroll of Maryland, a signer of the Declaration of Independence for whom Carroll Gardens is named.)

Recalling a dog that had been rescued from the frozen reservoir in Central Park a few weeks earlier, the residents agreed to try various methods to help the cat return to the ground. (The methods suggested to rescue the dog, who had been stuck on the ice for more than a week, included tying meat to a long rope, using shotguns to frighten him and make him jump over the railing, and lassoing him with rope lariats.)

On Saturday, women and children and a few grown men attempted to lure the cat down, but the kitty continued to grow colder while holding her stance. Not until Sunday, when, as the reporter pointed out, everyone should have been at church services, “did the entire masculine population in the vicinity turn out as a rescuing party.”

One of the would-be heroes, Mr. McKee, a Wall Street broker, brought a tiny “George Washington” hatchet he apparently had since childhood and suggested chopping down the tree. Not only did the property owner object, but nobody believed the man had enough strength and woodsmen skills to topple the urban tree.

Next, a lawyer stepped up and proposed using chloroform to put the cat to sleep so they could catch the unconscious cat as she fell to earth. The man spliced together several fishing poles. Then, fastening a slab of meat that had been saturated with the sleep inducer to the end, he raised the poles up toward the heavens until it was just a few inches from the kitty’s nose.

As the reporter noted, “Tabby persistently refused to either eat or smell, and the disciple of [Sir William] Blackstone was compelled to admit that the cat was wider awake than he was.” (I love the reporter’s sarcasm.)

Finally, little Willie came to the rescue. Placing his caged pet mouse at the foot of the tree, he instructed everyone to step back so the cat could see the tiny prey. Unfortunately, the cat did nothing more than let out a plaintive meow. As darkness fell and the winds sent 40-mile gales through the tabby’s whiskers, the rescuers returned to their homes with heavy hearts.

Now, Willie was not a quitter. All night long he dreamed of the cat and thought of ways to save it. The next morning, he enlisted his own cat in the rescue. He carried his cat to the base of the tree and began playing with it in the snow.

Still hanging to a topmost branch, the trapped cat watched in interest for several minutes. Then, more calmly than I imagine she climbed up the tree, the cat made her way down the trunk and joined in the play with Willie and his cat.

Willie took the cold and hungry cat to his home, where he and his parents, George and Mary Morton, cared for her while waiting for someone to claim the kitty as their own. (Perhaps the owner was none other than Dr. William H. Hale of nearby 40 First Place, who was found guilty of having too many cats in the early 1900s.)