Cats in the Mews: April 24, 1904

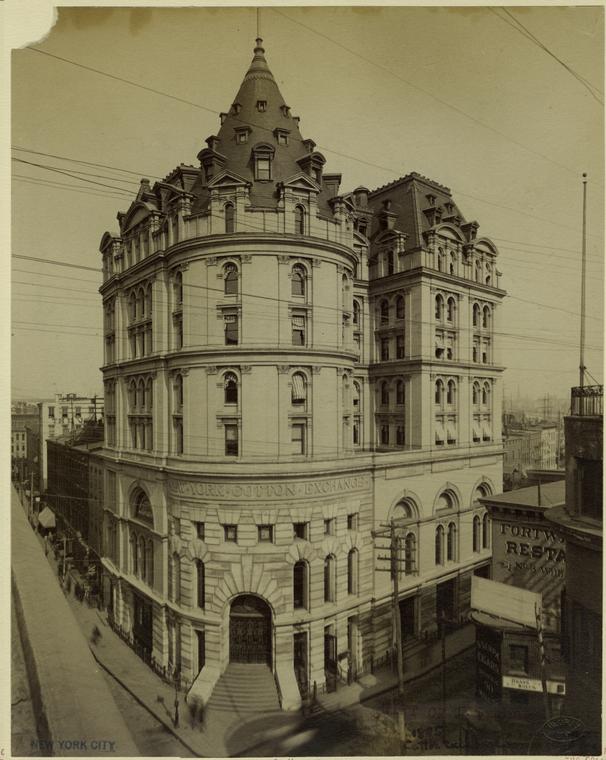

On April 24, 1904, The New York Times reported that Bull,* the famous black mascot cat of the Cotton Exchange, had gone on permanent strike. No longer would the cat visit the floor where the cotton brokers traded the commodity. No longer would he come up from the cellar, where he sometimes worked catching mice, and bring good luck to the trading floor.

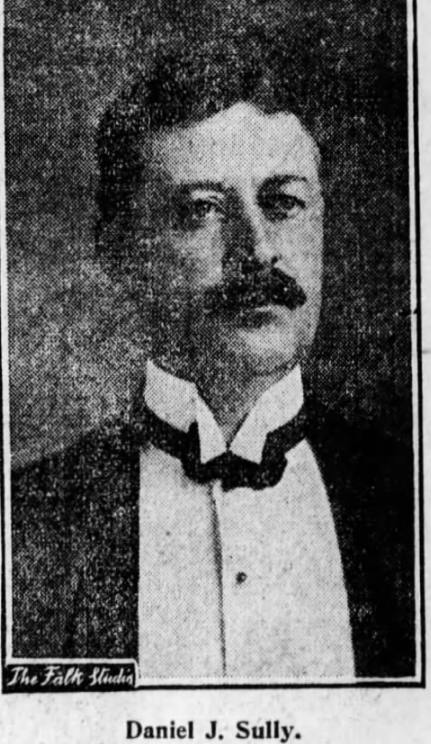

The strike came about one month after Daniel J. Sully, aka, the Cotton King, predicted a forthcoming cotton shortage. On that day, March 18, Sully also announced this his company could not meet its engagements on the Cotton Exchange. Within 20 minutes, the price of cotton dropped $13 a bale. Sully reportedly lost about $3 million in one day.

Many newspapers, including The New York Times, reported that Bull the cat was responsible for the sudden bear market and the Cotton King’s downfall.

*Bull’s full name was a popular one in the 20th century, but it is offensive today, so I have censored it.

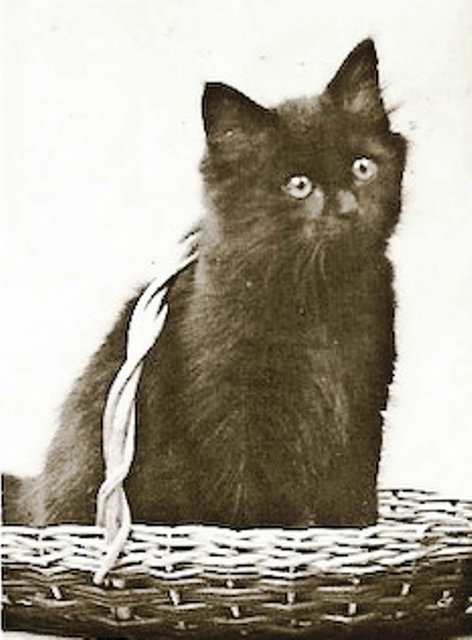

Bull, the Cotton Exchange Mascot

Bull was the beloved feline friend of Daniel J. Sully, aka, the Cotton King. Sully was a noted financier and an unscrupulous trader who, for 15 months, maintained complete control of the cotton market.

During his short reign, Sully “bulled” the price of cotton from 7 cents a pound to 17 cents a pound. The Cotton King credited Bull the cat with the bull cotton market.

Bull arrived at the Cotton Exchange building in 1901, when he was still a kitten. At that time, trading cotton was about as exciting as watching grass grow. According to The New York Times, it was so dull that the cotton brokers would while away the time by playing checkers and “swapping yarns.”

Here’s what the Times wrote about Bull’s debut at the Cotton Exchange:

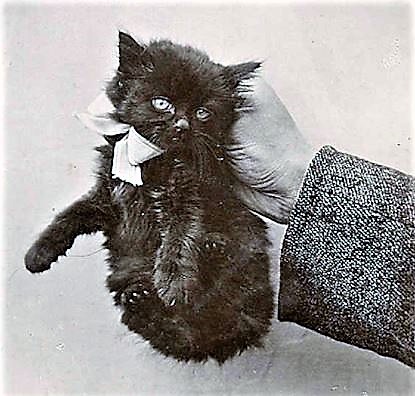

Three years ago…a bespattered kitten one afternoon dragged its weary way across the floor. It was so weak that its legs trembled under it as it walked, and its coat was covered with dust and grime. How it had managed to climb the stairs to the floor of the Exchange was a mystery that the brokers did not try to solve. It was enough that the feat had been accomplished, and the advent of the kitten was greeted with a ringing cheer.

In a moment there was a movement under way to purchase food for the newcomer. The hat of a broker was passed, and when it had completed the circle the generous sum of $10 had been secured. The janitor was summoned and admonished to feed and wash the cat, and to provide a place for it in the basement of the building. So well did he follow directions that the cat soon became a recognized member of the Exchange.

Three days after the kitten arrived, the market began to advance. Convinced that the cat’s arrival had something to do with this upturn, the traders summoned the janitor to the floor. He appeared with a clean and healthy kitten in his arms.

The cat jumped down upon the floor and rubbed himself delightedly against the legs of the amused brokers. The men gave the cat its offensive name and declared him to be their lucky mascot.

For the next three years, Bull spent some of his time mousing in the cellar, and most of his time drowsing on a radiator near the Hanover Square entrance to the Cotton Exchange building. (He also liked to sunbathe on the building’s roof.)

It wasn’t long before the traders made a connection between Bull’s movements and the market’s movement. Reportedly, whenever Bull moved his left hind leg for a stretch upward, the market was bound to go up. If he remained still and did not pay attention to anyone, the market was usually dead and lifeless. And when he wasn’t at his customary place on the radiator, it was the invariable sign of a falling market.

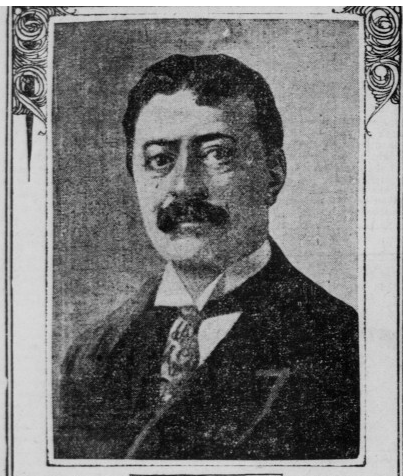

Daniel J. Sully, the Cotton Exchange Cat Man

When Sully became a member of the Cotton Exchange in early 1903, the men told him the history of the black cat. At this time, Sully and his partner, Edwin Haley, Jr., worked in their offices on the 23rd floor of the Wall Street Exchange Building at 43 Exchange Place. Sully loved hearing the story about Bull, so he walked one block south to the Cotton Exchange Building to meet the famous cat.

Right from the start, Bull and Sully hit it off. As their friendship developed, Sully became a cat man.

Soon, the other traders started to joke about all the pictures of Bull in his office. They also snickered at the black cat lapel pin that Sully wore on his coat every day. It wasn’t long before friends and family members began giving Sully all kinds of cat-themed gifts.

The New York Times described Scully’s office and his obsession with cats as follows:

There were black cats in various forms. Black cats sitting upon the crescent moon. Black cats carved upon decorated panels. Black cats embellishing match boxes and toilet sets. Mr. Sully received each particular gift with joy. His offices were made to resemble the noted “Chat Noir” of Paris.

Black cats were to be seen on every hand. On his desk upon a small easel was a handsome photograph of ** Bull himself; standing in front of a fireplace was an elaborate screen of silk on which was worked the figure of a black cat, the silk giving it a peculiarly lifelike appearance; occupying a conspicuous place against the wall was a large painting representing a black cat seated coquettishly upon the crescent moon.

“Bull is my mascot,” Sully told his friends whenever they mocked him for being a cat man. ” I admit that I have a certain superstition about it, and I am not ashamed.”

Somehow, Bull always seemed to know when Sully was at the Corn Exchange building. Even if the cat was reposing against a chimney on the roof of the building, he would quickly make his way back down the stairs to the trading floor. There, he would thread his way through the throng of rushing, yelling brokers until he reached Sully’s side.

Sadly for Bull, Sully was a busy man, and he often took trips to other cities where he had business connections. As the Cotton King’s attendance on the floor of the Corn Exchange became less regular, Bull began to feel less secure with his place in the world.

The Black Cat vs The Lawson Pink

One day in March 1904, Sully went to Boston to do business with Thomas W. Lawson, an author, horse breeder, and controversial Boston stock promoter. He stayed three days in Boston, which was the longest time he had ever been away from the Cotton Exchange. Bull began sulking about, no doubt convinced that his friend had abandoned him.

When Sully returned, the cat did not greet him with the usual leg rubbing. Instead, he stared coldly at Sully for a few moments, turned his back on the traitor trader, and walked away. Some suggest the cat was jealous of a “Lawson Pink” carnation that had taken the place of the black cat lapel pin on Sully’s coat.

For several days thereafter, Bull journeyed several times from his resting place on the roof to the trading floor, only to find Sully engrossed in business — and the “Lawson pink” flaring in his buttonhole. Four days after Sully returned from Boston, Bull disappeared.

It was at this exact time that the bears took over the market, and the prices of cotton began to fall.

At Sully’s orders, a search was organized to find Bull. The men looked on the roof and in the cozy warm box where the cat slept in the basement. He was nowhere to be found.

“If that cat can’t be found within twenty-four hours,” Sully was heard to say, ” I shall lose the fight.” By the end of the next day, Sully was bankrupt.

The Demise of Bull and Sully

Only eight months after Bull went on strike, the New York Times reported that the young cat had died at the Cotton Exchange. According to the paper, some said that Sully’s failure broke not only his soul and his bank account, but also the cat’s heart.

Sully sold most of his cat photos and other items to pay off some debts. A poster of Bull reportedly sold for $6.50, and the fire screen depicting the black cat sold for $4. Many of the items were later resold to members of the Cotton Exchange as souvenirs.

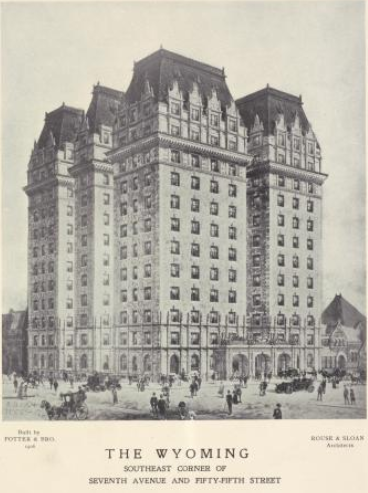

In February 1907, Sully nearly died from pneumonia. At the time, he was living in his new apartments in The Wyoming, on Seventh Avenue and 55th Street. Doctors did not expect a recovery, although the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported he was putting up a brave fight. His wife, Emma Frances Thompson Sully, theorized that the stress resulting from his financial downfall was exacerbating his weakened condition.

The Cotton King did recover; in fact, he did quite well for himself. In 1910, he invented a new type of cotton gin and launched a $10 million business in the British Isles. By June 1912, he was running a boarding house at Watch Hill, Rhode Island, which had previously been his summer home. He retired in 1915 and moved to Beverly Hills, California, in 1920.

Sully died of a heart attack at his home in Beverly Hills on September 19, 1930. He was just 69 years old.

Survivors included his wife, a son, Granville P. Sully, and two daughters, Gladys (Mrs. George Henry Mahlstedt) and Beth (Mrs. Jack Whiting — formerly Mrs. Douglas Fairbanks.) Sully’s grandson, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., was at his bedside at the time of death.

“At Sully’s orders, a search was organized to find Bull. The men looked on the roof and in the cozy warm box where the cat slept in the basement. He was nowhere to be found.”

Was Bull ever found, or did he just disappear into obscurity?

Sad to report, the men did find the cat, but only eight months after Bull went on strike, the New York Times reported that the young cat had died at the Cotton Exchange. According to the paper, some said that Sully’s failure broke not only his soul and his bank account, but also the cat’s heart.