On August 1, 1922, employees of the Flatbush post office sent out a BOLO (be on the lookout) alarm for their chief mouser, Bill. Described as a big, fluffy Maltese cat, Bill was responsible for keeping all the mice and rats in check at the post office.

He was also the beloved pet of the more than 100 employees on the postal staff.

Unlike the postal police cats of the General Post Office in Manhattan, who worked together in large groups, Bill preferred to work alone at the Flatbush sub-station of the Brooklyn Post Office. In fact, he worked just as hard to keep other cats away as he did to keep the mice at bay.

In other words, he got into a lot of cat fights with other felines hoping to steal his government civil service job.

Always victorious in these fights, Bill would often seek a quieter place to hang out for a while until his hot temper cooled down. Even when he disappeared for a few days to chill out, the gray cat always came back to the Flatbush post office.

But this time, he didn’t come back for many weeks.

Postal Clerk William Kuek, who was Bill’s main caretaker (and perhaps, namesake), told the Brooklyn Times Union, “If anyone sees a gray Maltese with a fighting disposition and a string of jingling bells around his neck,” they should let him know. Kuek also said he was almost certain the cat would return once he learned of a new ruling on postal cats that had just been wired from Washington, D.C.

According to the ruling, postmasters would be able to provide meat at the government’s expense for their office cat. Kuek explained that it required a little stretching of the law to make it possible, but the cats were very valuable to the postal service, so the funds could be justified.

“Every dog has his day,” Kuek said, “and from this time on, ‘tabby’ cat is to have money-bought food, if he happens to be a post office guardian. It is held that the cat is a protector of the government from the ravages of rodent pests.”

Bill the Cat Comes Back

On August 18, 1922, the Brooklyn Times Union reported that Bill had finally returned to the Flatbush Post Office, “and the smile is back again on the faces of postal employees.”

Kuek told the newspaper that he would make sure Bill got his fair share of meat that the government now provided for postal cats. He said he hoped the daily serving of meat would keep Bill satisfied at the Flatbush post office, and that he would no longer run away after a cat fight.

I have a feeling the prospect of a good daily meal led to many more fights with cats that wanted Bill’s job, but hopefully Bill had a long career with the Flatbush Post Office.

This concludes the story about Bill the post office cat of Flatbush. If you are interested in the history of Flatbush’s postal services, or want to learn more about the old post office where Bill lived and worked, continue reading. I had a lot of fun researching this history and finding dozens of tiny pieces to put the entire puzzle together.

An Epic History of the Flatbush Post Office

The history of the Flatbush post office begins with a rural postmaster named Michael Schoonmaker, who ran a grocery store and a roadside tavern and inn on Flatbush Avenue. It also features an enterprising stage coach operator named Colonel James C. Church, and an ambitious young letter carrier named John F. McCarthy.

Schoonmaker, the third postmaster of Flatbush (preceded by Abraham Van Deveer [1814] and John Leffers [1819]), collected and sorted mail for the farmers and other residents at his grocery store from 1829 to 1845. Church delivered the mail to the first Flatbush post office. And McCarthy spent many years as a letter carrier, eventually becoming the first superintendent for the Flatbush post office when the town was incorporated into the City of Brooklyn in 1895.

The Early Years of the Flatbush Post Office

In the early 19th century, before there was a post office in town, a Customs House clerk from East Flatbush named Cornelius Duryea picked up and delivered mail for Flatbush residents on his daily trips to the City of Brooklyn. The town’s first post office was established in the 1830s, when Colonel James C. Church started a daily mail-coach route between Fort Hamilton and Flatbush.

Church was the postmaster for the Fort Hamilton post office, which was located in his general store on the shores of the Narrows, at the foot of the State Lane (Fort Hamilton Avenue). His mail coach route ran through Bath Beach and along the King’s Highway to Flatbush, serving the post offices at Flatbush, New Utrecht, and Fort Hamilton. He also ran a passenger stage coach from Fort Hamilton to Fulton Ferry in the City of Brooklyn; the fare was 25 cents.

At this time, the Flatbush post office–which served all of Flatbush, Gravesend, and Canarsie–was located in the corner of Schoonmaker’s grocery store on Flatbush Avenue, across from the Reformed Dutch Church and adjacent to the Erasmus Hall Academy. The grocery store and post office were housed in a building that was described by The Chat newspaper as “a one-story and attic structure, with a porch extending across the front but a few inches above the sidewalk and protected with a roof.”

Mail bags for collection and delivery to and from all parts of the world would be picked up and dropped off at Schoonmaker’s once a day via Church’s mail stagecoach. During the busy summer months, Church would make two daily mail trips.

When the mail arrived, Schoonmaker would leave his roadside tavern in the old Catherine Lott homestead and cross the street to his grocery store. There, he sorted the the incoming and outgoing mail. Since there was no house-to-house delivery, residents had to pick up their mail at Schoonmaker’s store or rely on neighbors or travelers to bring it to them.

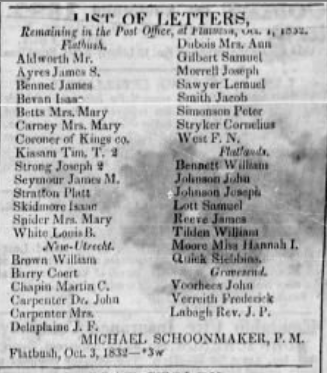

If residents did not collect their mail, Schoonmaker would publish an ad in the newspaper, like the one below. It cost three cents to mail a letter from the post office.

Following Schoonmaker’s death in the 1840s, his wife took over the tavern and the postal job, becoming the first postmistress of Flatbush. In 1845, their son, Richard L. Schoonmaker, was appointed postmaster.

The following is from an article published in the Brooklyn Standard Union in December 1900 describing the daily mail delivery in the 1840s:

“At 9 A.M., with a loud blast of the horn and great prancing of steeds, the heavy mail coach, drawn by four horses, would rumble down the post road from New Utrecht [now Church Avenue], turn the corner by the old Dutch Church and draw up before the quaint old inn of the widow Schoonmaker.

The mailbag would be taken over to the post office, opposite the church, and its contents sorted by widow Schoonmaker, the postmistress. It was then flung up to the driver, who deposited it under the boot at the foot of his high seat, and with a loud snap of his long whip and a still louder blast of the bugle, the cumbrous vehicle would disappear in a cloud of dust down the turnpike, to return at 5 P.M.”

The Flatbush Presidential Post Office

In the later half of the 19th century, the Flatbush post office was operated as a Presidential post office. Presidential post offices served as a collection depot for mail, but there were no delivery services.

Each post office had a postmaster who sold stamps and money orders and sorted the mail for the customers’ collection boxes. Total annual revenue determined whether the post office would be classified as a first-, second-, third-, or fourth-class facility. The postmasters were appointed by the President of the United States; thus, if the president was a Republican, the postmaster and clerks would also be Republican.

Postmasters received a small salary from the government for their services, which was based on the classification. The classification system incentivized them to sell as many stamps and money orders as possible, but it sometimes led to grifting and other scandals.

Most postmasters had at least one other job, such as selling books, medicines, and stationery, or working as a shipping agent. As long as the post office was not too busy, they were able to work at both occupations in the same location.

During this time period, Flatbush had several postmasters, and each man operated the post office out of his own place of business. (One woman, Miss. Phebe J. Case, was postmaster from 1865 to 1870; there is no other published information about this woman.)

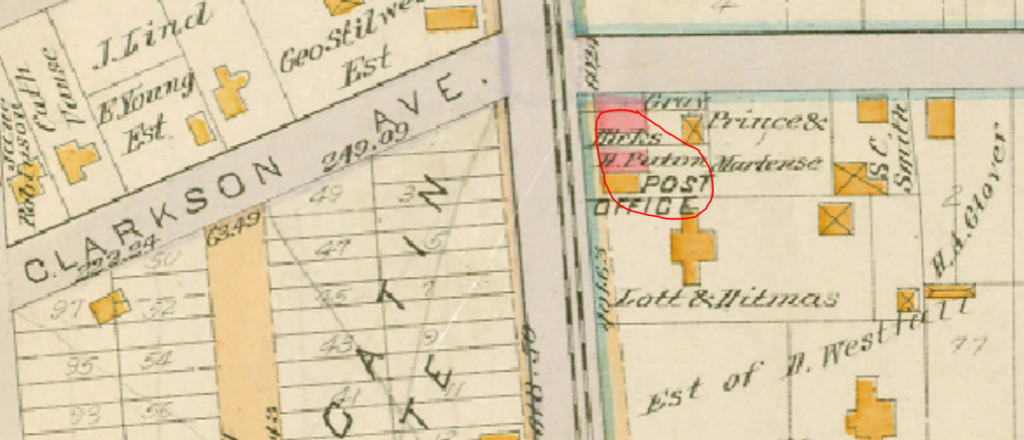

From 1876 to 1882, Gibert Hicks ran the post office from his two-story brick store on the corner of Flatbush and Clarkson Avenues. When Thomas Moorehead took over, he removed the post office to his store across from the Reformed Dutch Church (where the original post office at Schoonmaker’s had been.)

In 1884, Henry Paton was appointed postmaster. He moved the post office back to the intersection of Flatbush and Clarkson Avenues, where his family lived and ran a harness shop in a two-story brick building next to Hick’s store (the building was across the driveway that led to Hick’s stables, as noted on the map below.)

The post office was not in the harness shop proper, but in a one-story frame structure that was eventually detached from the harness shop. According to the Brooklyn Times Union, this building was so cramped, “it had barely room to swing a cat in.” Luckily, Bill the cat did not live and work in this building.

Because most residents of the town had to travel two or three miles to get their mail, there was much discussion during this time about implementing free delivery services. In the meantime, those who did not want to walk or ride into town had to rely on a young man named John McCarthy.

Flatbush Post Office Superintendent John McCarthy

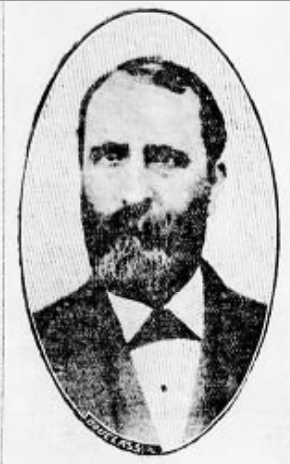

Born in the Town of Flatbush in 1868, John F. McCarthy received his early education at the school for boys at Holy Cross (present-day St. Gregory’s Academy on Church Avenue) in Flatbush. He then attended St. Francis Academy on Baltic Street. When he was just 16, his father, James, died, leaving John in charge of supporting himself and his mother, brother, and sister.

McCarthy’s first job was as a clerk at the Kings County penitentiary. To supplement his small income, he came up with an idea to deliver mail to the residents in the far reaches of Flatbush. He correctly assumed that many of his fellow rural residents would prefer having their mail delivered to their home every day rather than picking it up in town at the Flatbush post office.

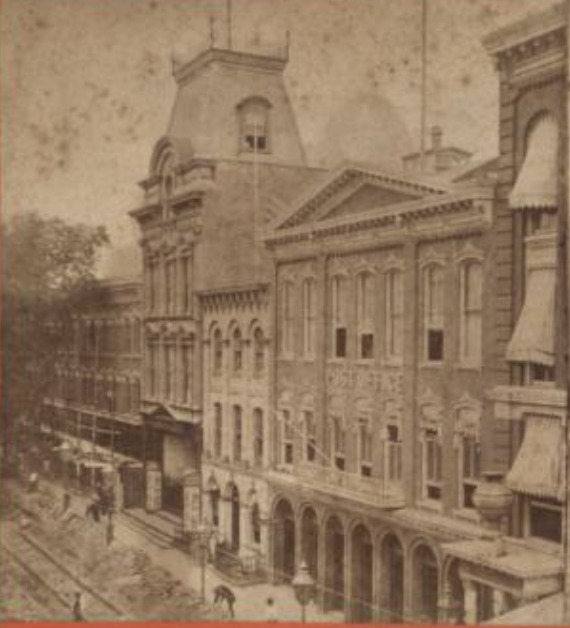

McCarthy established his business with several hundred residents, who paid him two cents for every piece of mail delivered. It took him all day and night to pick up the mail from Brooklyn’s General Post Office on Washington Street (pictured at right) twice a day and deliver it to his customers–his route was extensive and the country roads were poor. But as Flatbush continued to grow, so did his business.

In 1895, McCarthy got a full-time job working as a clerk in the Flatbush post office, which was then under Democratic President Grover Cleveland. Five years later, in 1890, Charles H. Zelinsky was appointed postmaster of Flatbush by Republican President Benjamin Harrison. McCarthy, a Democrat, lost his good-paying job.

Fortunately, McCarthy had never given up his side job delivering mail to hundreds of paying customers. The money he earned from delivering mail was sufficient to support his widowed mother until he could secure another good postal job under a Democratic president.

Toward the end of 1893, the Democratic Association of Flatbush passed a resolution asking President Grover Cleveland to appoint McCarthy as postmaster of the Flatbush post office. The appointment was not needed: In 1894, when Flatbush was incorporated into the City of Brooklyn, the Flatbush post office became a sub-station of the Brooklyn General Post Office. The old Presidential postal system was finally replaced by a carrier station in Flatbush.

Unlike the Presidential system, the carrier service fell under the Civil Service Commission and did not require political appointment or loyalty. It also replaced the position of postmaster with a superintendent. And, the new carrier system required something Flatbush did not yet have: numbered street addresses for private residences to make home delivery possible.

In March 1894, Brooklyn Postmaster Andrew T. Sullivan appointed McCarthy as superintendent of the new Flatbush sub-station, aka, Station F. Sullivan based his hiring decision not on politics but on the many endorsements the young man had received from the residents of the town. The new Station F post office at 809 Flatbush Avenue opened on March 1, 1894.

Mail delivery began on May 16, 1894, with six letter carriers reporting to McCarthy: Edward R. Burt, Michael Rutledge, Tom Easop, Harry Ahearn, Tom Burney, and Louis D. Ryno. They made four deliveries a day. (When he retired in 1920, Ryno estimated he had walked millions of miles delivering mail along his route from Lenox Road to Malbone Street and from Rogers to Albany Avenues.)

Sadly, McCarthy took gravely ill shortly after taking over the new post office. Although he realized that death was near, he continued working until he was too weak to leave his house.

On December 17, 1895, at the age of 28, McCarthy died of consumption in the home he shared with his mother on Nostrand Avenue. As the Brooklyn Times Union noted, “He was honest, honorable, and reliable in every respect. Those who knew him best loved him most. In his death the people of Flatbush has sustained a loss.”

Postmaster Richard Flannery

Richard A. Flannery, formerly a chief clerk of Station U on Fifth Avenue and 12th Street, was immediately appointed to fill McCarthy’s former $1,000-a-year position.

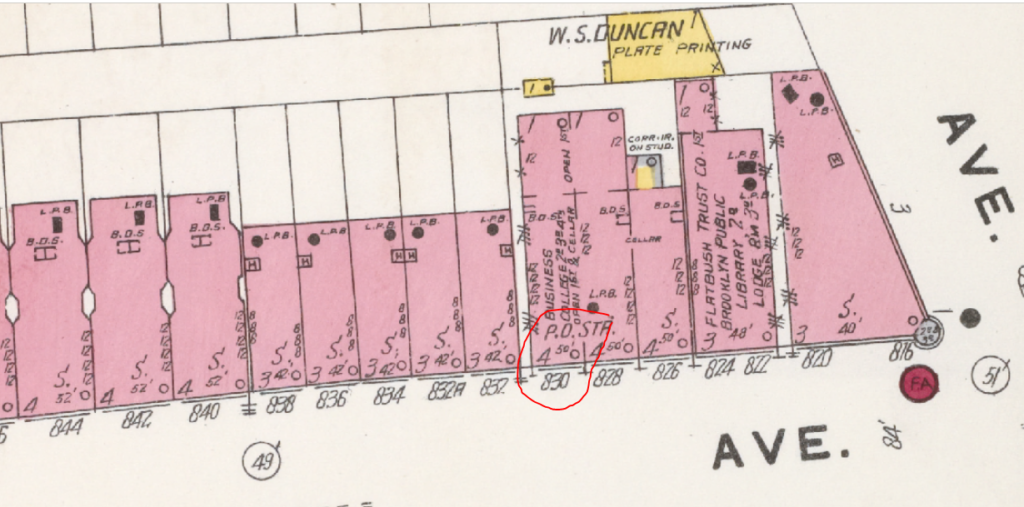

Under Flannery, with Flatbush experiencing exponential growth, the post office moved directly across the street into the second floor of the new, four-story Reis and Davenport building at 830 Flatbush Avenue, just south of Caton Avenue. That year, 1896, the number of carriers increased to nine, and the number of deliveries increased to five per day.

Over the next few years, the post office was expanded two times (notice the rear extension to the building in the map above), more than doubling in size. It remained at this location until 1913.

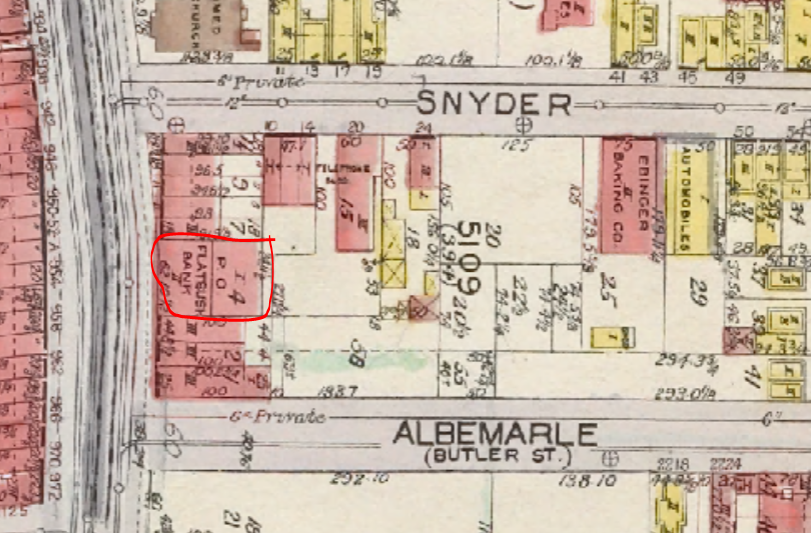

In 1913, a new Flatbush Post Office was constructed on Flatbush Avenue between Snyder Avenue and Albemarle Road. The new facility shared the building with the Flatbush Savings Bank.

It was here that Bill the cat was working when he disappeared in 1922. During this time, William F. Costello was the superintendent. (Perhaps the superintendent was Bill’s namesake?)

Two years after Bill the cat disappeared and reappeared, the Flatbush Post Office moved one block east to a building at 2265 Bedford Avenue. The modern brick and limestone building was considered the nicest sub-station in Brooklyn, with 8,000 square feet of space on the first floor, plenty of ventilation, and lots of windows for selling stamps and money orders.

Hopefully, when the 108 employees moved into the new building on April 1, 1924, they took Bill the cat with them.

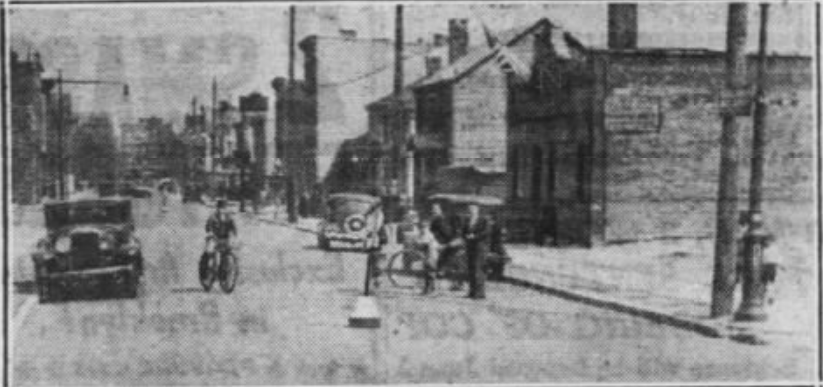

When the lease expired on this building in April 1934, the post office moved into a brick factory building on the southeast corner of Erasmus and Lott Streets. The problem with this temporary location was that the street was considered a “play street” for young boys. Patrons often complained that they could not get their vehicles down the street or that their car windows had been broken by batted base balls.

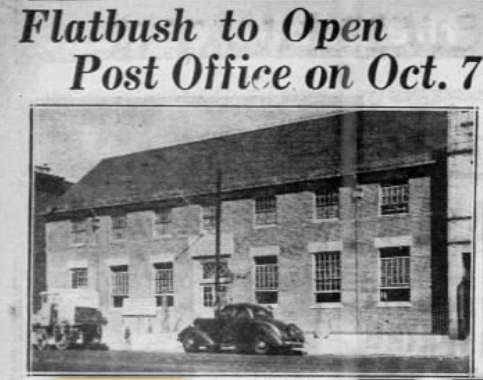

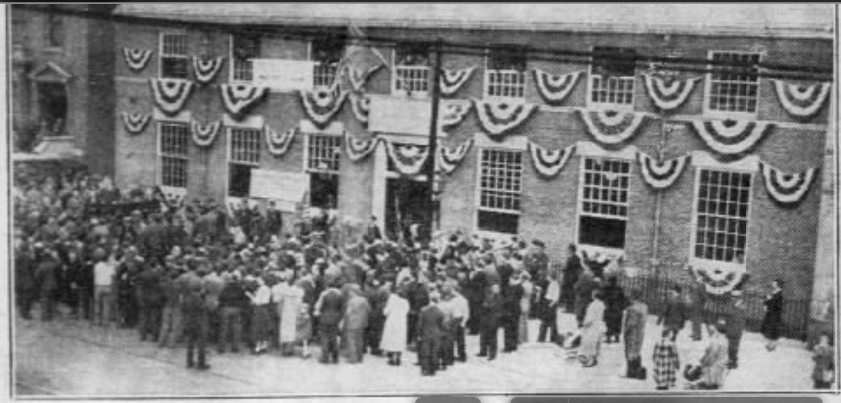

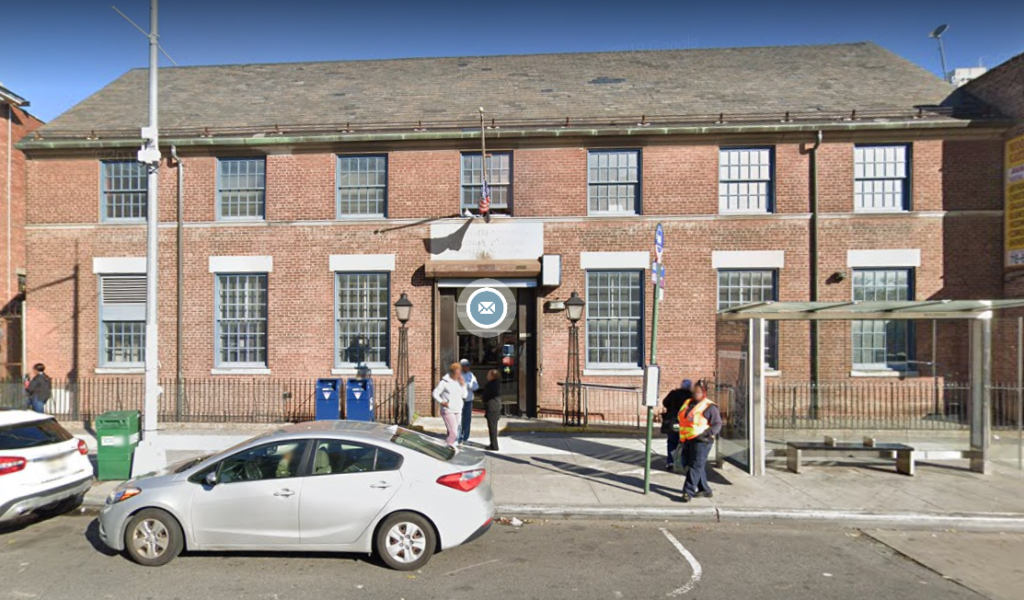

In August 1934, a new site at 2273 Church Avenue–previously occupied by an auto repair shop and a blacksmith, and then occupied by a used car lot–was selected for the next and current Flatbush Post Office. A dedication ceremony for the $140,000 facility took place on October 7, 1936.

I loved all the background information and photos on this story about Bill the cat. Thank you!