I recently wrote about a cat named Bill who was the champion mouser of the Flatbush Post Office in Brooklyn in 1922. The following tale takes place four years later, and features a lucky cat and several unfortunate rabbits that were mailed to the Brooklyn General Post Office.

On December 12, 1926, the Brooklyn Times Union published a small article titled “Cat Arrives by Mail.” According to the article, employees of the Brooklyn General Post Office were very surprised to hear a plaintive meow coming from a small crate. Inside the crate, which had arrived via the Railway Mail Service, was a pretty little cat.

Apparently, the cat and crate originated in Morrisville, a village in Central New York. The feline package traveled by train on the New York, Ontario and Western Railway, and was then taken by a postal vehicle from the train station to the Brooklyn Post Office.

Upon the cat’s arrival in Brooklyn, Brooklyn Postmaster Albert B.W. Firmin (appropriate name for this story!) examined the cat and determined that she was in good health and had made the trip unharmed. He did note, however, that the cat was very sleepy, which he attributed to her strange and scary experience.

The clerks carried the crate to the miscellaneous mail section, where Superintendent McCann and his associates fed the cat and tried to make her feel at home. The intended recipients of the cat were contacted and advised to come to the post office to pick up their precious package.

Firmin told the press that animals were not allowed to be transported by mail. He said the cat should have been adopted by the Morrisville post office employees instead of being transmitted by train along a U.S. postal route.

The postmaster further explained that while the Brooklyn General Post Office had many cats of all varieties and ages on its staff to prevent the ravages of rats and mice, there were no accommodations for traveling cats in the postal service. “From the standpoint of kindness to animals,” he said, “no cat in a crate should be permitted transportation by this means.”

Incidentally, on that very same day, the post office received four rabbits intended for someone named Mr. McGann. These were not live rabbits, however. They had all been previously killed, and it was surmised that “someone had mailed them in evidence of his prowess as a hunter.”

Postmaster Firmin was very angry with this delivery, and he told the reporters that dead animals should also never be mailed. He gave orders to resort to every means to locate the owner of the rabbits before he notified the Board of Health. He also reported the matter of the cat to the U.S. postal employees in Washington so that they could take disciplinary action against this wrongdoing.

Cats in the Brooklyn General Post Office

Although the Brooklyn General Post Office had many cats on the payroll in the 1920s, there were no Brooklyn postal cats in the early 1900s, and no intention to establish to hire any at that time. (The New York General Post Office had great success with its feline police force in the early 1900s, but Brooklyn Postmaster George H. Roberts Jr. was reluctant to hire cats before Congress appropriated funds for their “maintenance.”)

In April 1902, a woman from Fort Greene Place wrote a letter to Postmaster Roberts stating that she had read in the paper that the post office needed cats to control the rats who were attracted to the paste and gum used on envelopes.

She wrote, “Now, I have a beautiful Maltese cat and four kittens, 5 weeks old. They are black and one a dark Maltese. I must dispose of them. So, if you would like to adopt this dear little family, or part of it, I will send them by express, prepaid.”

Roberts was a kindhearted man who did not want to hurt the woman’s feelings by rejecting her offer. As the Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted, “Some clerk will have to decide the cat question for the administration, as the Postmaster doesn’t feel competent to do so.”

If you enjoyed this story, you may also enjoy reading the Christmas kitten mailed to Yorkville in 1906. If you are a history buff, following is a condensed history of the Brooklyn Post Office.

A Brief History of the Brooklyn Post Office

During the colonial era, the early settlers of Long Island (of which the village of Brooklyn was the main settlement) had two ways of getting their mail: they could either pick up their mail directly from the captains arriving on ships from Europe, or they could rely on friends and travelers to bring their letters to them directly or via a relay system.

Coffee houses served as the first unofficial post offices, where unclaimed mail coming off the ships would be placed on open racks and picked up by travelers on their way to Long Island, New Jersey, or Westchester County.

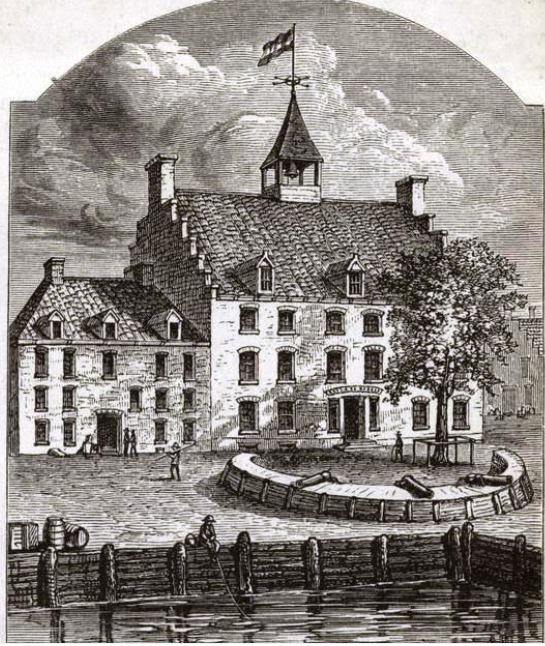

In 1642, William Keift, Governor of New Amsterdam, built a stone structure at Coenties Slip and Pearl Street. The five-story building was first called Stadt Herberg or City Tavern; later it would become the Stadt Huys or State House, New Amsterdam’s first city hall.

The City Tavern served as a community center and an inn for travelers. It was also here that letters for the settlers of Brooklyn, Gowanus, Bergen, Wallabout, and other areas of Long Island were placed on racks for hand delivery.

If a traveler saw a letter addressed to someone he knew, or someone he was visiting on Long Island, he would take the letter off the rack. Oftentimes a letter would be passed through several travelers’ hands on its journey from New Amsterdam to Long Island. There were no bridges; travelers to Long Island had to take a ferry service (basically a row boat) first operated by Cornelis Dircksen.

This tavern/coffee house system continued until 1686, when all mail brought in by ships had to go through the British custom house.

In 1764, the first postal route, known as the circuit, was established on Long Island. Mail was carried twice a month by horse and rider along the north shore of the island, returning along the south shore. Some villagers were rather resourceful: In the town of Quogue, in Suffolk County, a tree served as the “post office” for the residents, who would leave and pick up mail in a hole carved into the tree.

In Brooklyn, some sort of postal services began in July 1803, when a man named P. Buffet was appointed postmaster of Brooklyn. Very little information has been published about this man or where the post office was located, but it was most likely near Fulton and Front Streets.

In 1806, a shopkeeper named Joel C. Bunce was appointed postmaster for the village of Brooklyn. He and his partner, Thomas W. Birdsall, had a general store near the East River ferry on the corner of Old Ferry Street (Fulton Street) and Front Street. Sometime around 1815, this store was designated an official post office.

Following Bunce’s death in 1819, Birdsall took over the postmaster job until 1822. He was succeeded by George L. Birch, Thomas Kirk, and then Erastus Worthington, a writer for the Long Island Star who was appointed in 1826.

Brooklyn Post Office Headquarters

In its early years, Brooklyn’s post office occupied numerous shops leased by the Federal government. As an article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted in April 1867, “Since our respected ‘Uncle Sam’ stubbornly and foolishly refuses to provide himself with an establishment of his own in Brooklyn he must be content to share the fate of humbler mortals, and move whenever he choses to indulge in the luxury of disgracing with his landlord.”

Under Postmaster Worthington, the post office was located in his stationery and book store at Fulton and Hicks Streets. Under Birch, it was located at 97 Fulton Street. Around 1829, another stationer and bookseller named Adrian Hegeman took over as postmaster and moved the post office to his shop across the street, where it remained for the next 12 years.

When Postmaster George Hall (who was also Brooklyn’s first mayor) took over in 1841, the post office was moved to a small room on Hicks Street across from Doughty Street. Hall soon secured funding to build a grand new structure on Cranberry Street, between Fulton and Henry Streets. In addition to Hall, there was one clerk—Mr. Joseph M. Simmonson—and one single letter carrier named Benjamin Richardson, who, accompanied by his dog, made two deliveries a day between Manhattan and Brooklyn.

Henry C. Conkling was appointed postmaster in 1845. Once again, the post office moved, this time to 147 Fulton Street, between High and Nassau Streets. This building was destroyed in a large fire on September 9, 1848, that started in George Drew’s upholstery and furniture store on Fulton Street and destroyed seven blocks of wooden buildings; postal services were temporarily moved to the Apprentice Library on the corner of Henry and Cranberry Streets.

Next, the post office moved to the Montague Hall building (concert and assembly rooms) on Court Street, and from there it moved to 337 Fulton Street near Rockwell Place–under Postmaster Daniel Van Voorhis–where it remained until 1857.

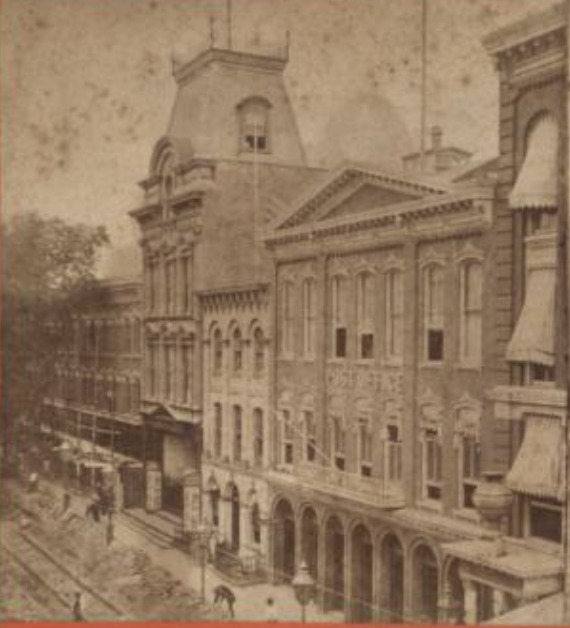

During the 1860s, under Postmaster William H. Peck, the main post office was located in a building on Montague Street near Court Street. When the rent was raised, Colonel Samuel H. Roberts, Brooklyn’s eighth postmaster general, secured a vacant lot on Washington Street between Johnson Street and Myrtle Avenue, next to the 41st Precinct Station House and, later, the Brooklyn Theatre (now the site of the Kings County Supreme Court). The new post office building was completed in 1867.

At this point in time, the Brooklyn Post Office had two post offices (the other one was in Williamsburg) and 60 employees, including 13 clerks, 32 carriers (who delivered about 5,000 letters and 1,000 newspapers a day), and four collectors of letters from the lamppost letter boxes. Prior to 1861, postal carriers were allowed by law to collect one cent on each letter delivered. The post office established the free delivery system in July 1861, which set annual salaries for the carriers.

In the early 1880s, the Federal government finally decided that Brooklyn deserved a much grander building for its postal services. Several sites were considered for a joint Federal Building/Post Office, including one on the corner of Fulton and Flatbush Avenues and the site of the old Dutch Reformed Church between Joralemon, Court, and Livingston Streets.

Finally, a real estate investor named Leonard Moody was authorized by Secretary of the Treasury Charles J. Folger to purchase a site on the corner of Washington (now Cadman Plaza East) and Johnson Streets–provided he could do it for a cost no more than $450,000.

Eighteen people owned the property, so Moody had to dance around and make deals without letting anyone know what the property was going to be used for. If it leaked out that the government was planning on purchasing the land for a federal building, all the property owners would have jacked up the buy-out price.

Within five days, all the property had been secured at a cost of $165,00–just $15,000 more than what the government wanted to pay. Work on the four-story Romanesque-Revival-style building of Bodwell granite began in 1883 and was completed in 1891. The Brooklyn Post Office moved into the building in 1892.

Five years later, in 1897, the New York Mail and Newspaper Transportation Company (a subsidiary of the American Pneumatic Service Company), opened its the 27-mile pneumatic mail tube system connecting 22 post offices in Manhattan and the new Brooklyn General Post Office.

The Brooklyn General Post Office is one of the few historic buildings to escape the wrecking ball when Cadman Plaza was built in the 1950s. The building was renovated and expanded in 1999, and today it still houses postal services as well as the US Bankruptcy Court, the US Trustee, and the Offices of the US Attorney.