The following story explores Camp Thomas Paine in Riverside Park, one of the many Depression-era Hoovervilles (aka tent cities or shanty towns) that proliferated public parks in New York City in the 1930s.

This story is more than a simple tale about two pet pigs that lived among the 125 men at Camp Thomas Paine. It is a story about a fascinating commune of WWI veterans who thought out of the box, so to speak, to survive in 52 makeshift shacks along the Hudson River from 1932 to 1934.

And it is, in part, a commentary on a sad and shameful period in our country’s history.

The Resourceful Beginnings of Camp Thomas Paine

In August 1934, an auction took place at Patrick Joseph Cain’s theatrical storage warehouse at 530 West 41st Street. Described as a “red-brick mausoleum,” Cain’s warehouse was the final resting place of all Broadway shows, good and bad.

About 100 people attended the auction, in search of West Point uniforms, boxes of humming bird dress ornaments, Japanese trees made of shells, three large mechanical elephants, a mechanical cow used by W.C. Fields, a saddle that Will Rogers used on a prop horse, and photographs of famous Broadway stars. All of these items had been featured in a series of elaborate theatrical revue productions on Broadway called the Ziegfeld Follies.

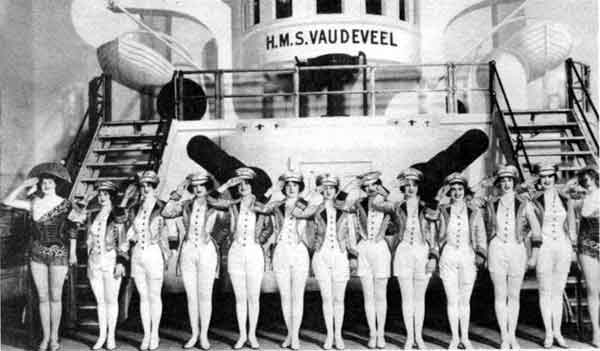

Noticeably missing from the auction was the scenery once used on the stages to prop up the famous chorus girls known as the Ziegfeld Girls. According to the press, the canvas sets and lumber had all found its way to Riverside Park two years earlier, in August 1932, where it was used to construct some of the shanties and other structures for the veterans who founded Camp Thomas Paine.

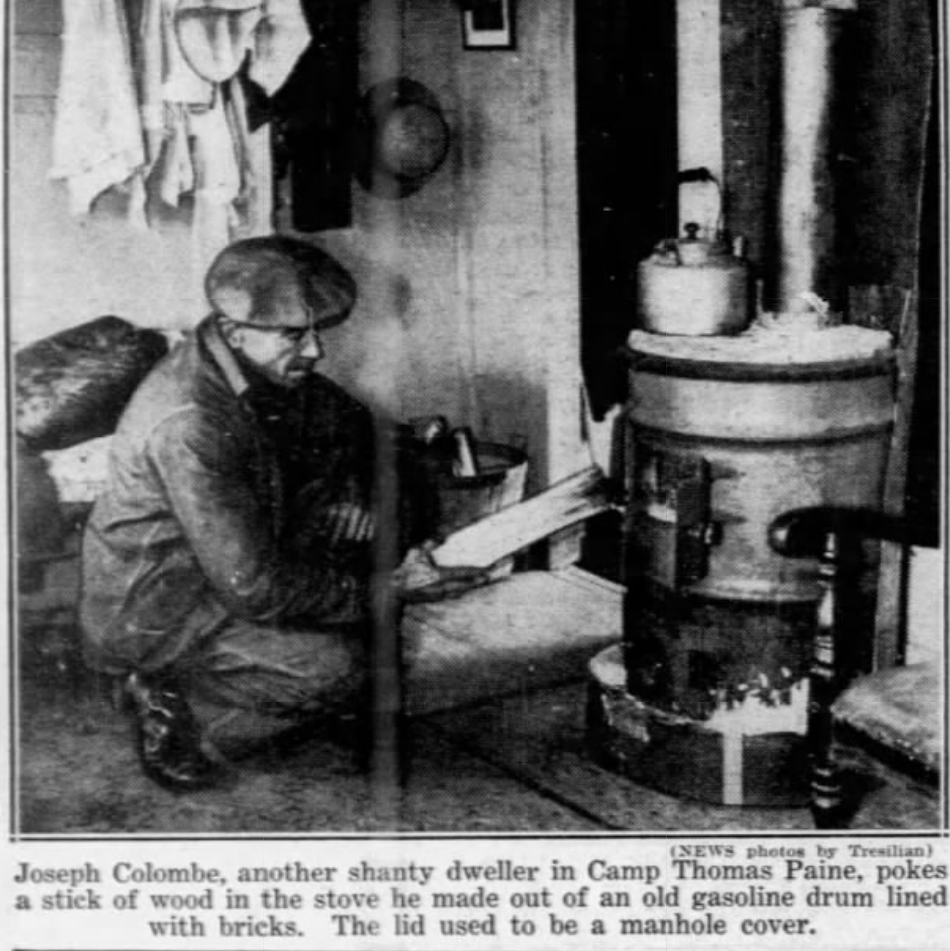

Using the stage lumber was one of the many ways the down-and-out men demonstrated their resourcefulness. By the time the veterans were evicted from the colony in May 1934, they had established a large garden, a mess hall with a communal kitchen and cook stove, and a rec hall with a stone fireplace. They also received a faucet for running water and street lamps from the city, and set up a savings account at the Corn Exchange Bank.

From the Anacostia Flats to Riverside Park

Camp Thomas Paine was founded by 75 jobless World War I veterans who had previously taken part in a large group of suffering and desperate vets called the Bonus Expeditionary Forces (BEF). The goal of the of the BEF was to get a government-promised bonus payment of $1 a day immediately, rather than wait until 1945, as the federal Bonus Act stipulated.

Led by Walter W. Walters, the veterans occupied camps and buildings in several locations in the District of Columbia from May to July 1932.

On July 28, 1932, Attorney General William Mitchell ordered the DC police to remove the veterans from government property. Although the men had an ally in Brigadier General Pelham D. Glassford–now superintendent of the DC police–they could not beat General Douglas MacArthur, Major Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Major George S. Patton.

Once these top military men received orders from President Herbert Hoover to shut down the camps, the Army troops advanced with tanks, bayonets, and tear gas to drive the men out and across the bridge.

The Washington Daily News called the military ambush “A pitiful spectacle” to witness “the mightiest government in the world chasing unarmed men, women, and children with Army tanks. If the Army must be called out to make war on unarmed citizens, this is no longer America.”

Having been driven from their camps in the nation’s capital, 75 men headed north to New York City to set up Camp Thomas Paine. They named the main “road” through their colony Glassford Avenue in honor of the DC police superintendent. Each shack was given a numbered address and christened with comical names such as Grand Hotel, Rain Inn, and The House That Jack Built.

Commander John B. Clark

The chosen leader of the camp was Commander John B. Clark, who ran the commune like a military facility.

Only men with an honorable discharge were allowed, and they all had to abide by military discipline. The men took turns doing guard duty, and no liquor (not even beer), women, or children were permitted in the camp. Violators of camp rules were expelled.

For two years, as many as 125 war veterans of multiple races and nationalities lived and worked in harmony. They carried barrels of water into the camp for cooking and cleaning (until the city installed a faucet), collected driftwood from the river to burn in their fireplace, and gathered loam in wheelbarrows to create a vegetable garden where there was once only stones and cinders.

The men also built a rec hall that was paneled with partitions from a branch office of the failed Bank of United States. The hall also featured canvas sets from “A Night in Paris,” “Naughty Naughty,” “Three’s a Crowd,” and many other Broadway shows–all courtesy of Cain’s theatrical storage warehouse.

Life at Camp Thomas Paine

Although the men took pride in their independence and never begged on the streets, they weren’t too proud to accept charity. The Horn & Hardart company donated 24-hour-old baked goods to the camp every day. This allowed the men to eat pie twice a day, except on Mondays.

They also received bags of potatoes, onions, oysters, clams, and meat from community leader and activist Lewis S. Davidson, for whom the Lewis Davidson Houses in the Bronx are named. Jacob Klein, a lawyer, sent the men a $5 check every week. And their neighbor, Charles Schwab, sent the men excess produce from his farm in Pennsylvania.

While food was always available, the men did not have all they needed to fully live even a semi-comfortable life. There were very few coats for the men in the winter, and men’s suits were in short supply. The camp did not provide coal and kerosene, which the men needed to keep their shacks lighted and warm, and there was no facility for the men to take showers.

Sometimes the men would find odd jobs, such as shoveling snow, polishing automobiles, or scrapping newspapers and metal. They would turn in their money to the camp communal fund, which was kept in an account at the Corn Exchange Bank (at one point the account had about $105). Monies in this fund were used to purchase milk and sugar and other needed supplies.

If any man found a steady job, he was allowed to stay at the camp for one more week; he also had to contribute a third of his pay for that week. Then he was asked to move out to make room for someone less fortunate on the waiting list.

The Pets of Camp Thomas Paine

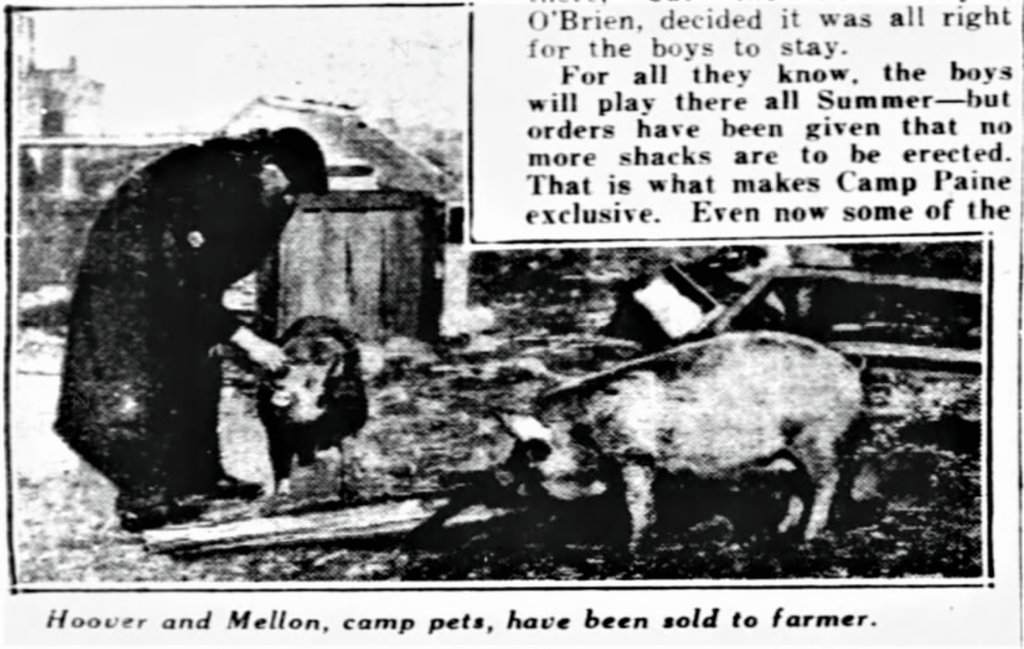

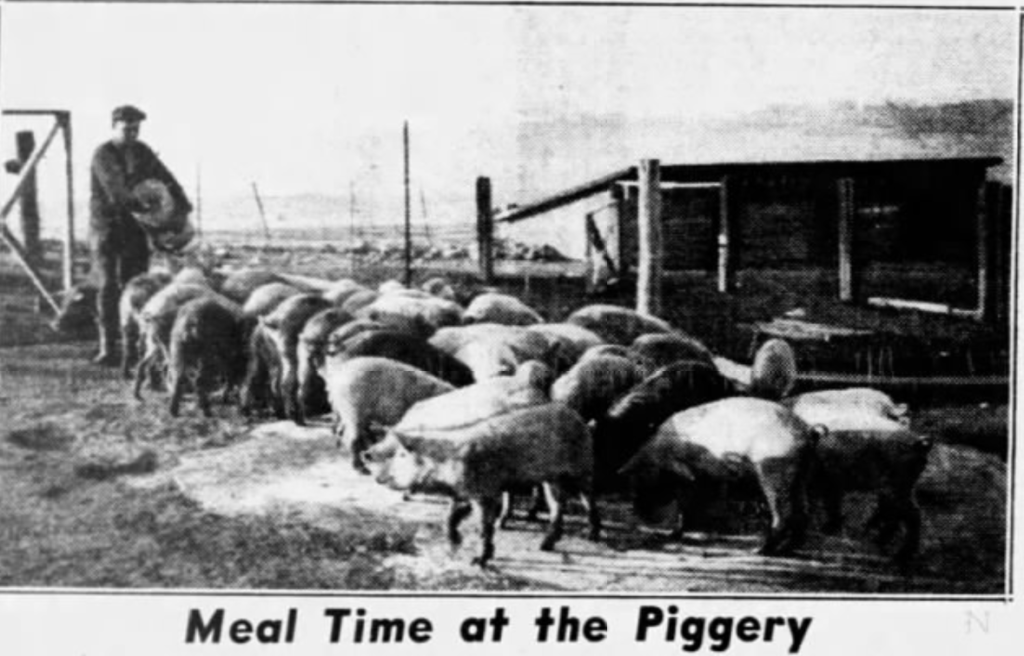

One of the most unusual elements of the settlement was the corral filled with pet animals, including the two pigs and dozens of rabbits, turkeys, ducks, and chickens. (As The New York Times noted, the camp was a sanctuary for every living thing that was an outcast, miserable, or unwanted.)

These animals, for the most part, were the men’s pets. Commander Clark told a reporter, “Nothing that enters this camp alive will ever be killed.”

The pigs–Andy Mellon and Herbert Hoover–were a gift from the Veterans of Foreign Wars. At first, the men intended to eat the pigs. But the pigs were so friendly–they would follow the men around like pets dogs would do–they didn’t have the heart to kill their new companions.

Clark told one reporter, “They’re eating what’s left of our food. But they have become our pets; if we killed them the boys couldn’t eat them. If we sell them someone else will eat them.”

They eventually sold the pigs to a farmer for $5. The men later learned that either Mellon or Hoover was not properly named, as one had given birth to several piglets.

By the spring of 1933, the camp had three pet turkeys and two ducks, which swam in an old iron sink that was sunk in the ground. They also received three rabbits, which turned into 24 rabbits a few months later.

One of the bunnies was the gift of a little boy who had received the rabbit as a present for Easter. His family wouldn’t let him keep it in the house, so he brought it to the camp so the men could care for it.

In addition to the barnyard animals, there was at least one domesticated dog and one cat that lived at Camp Thomas Paine.

According to The New York Times, a Philippine veteran named Estanasiao Labo had a fox terrier and a gray cat that had a “curious smudge” on its nose. Labo reportedly spent a lot of time sprucing up his shack for the holiday season; when a reporter came to visit, the dog was lying in front of his door and the cat was snoozing on a pile of boards. Commander Clark told the reporter, “Yes, I think the happiest man would be Labo.”

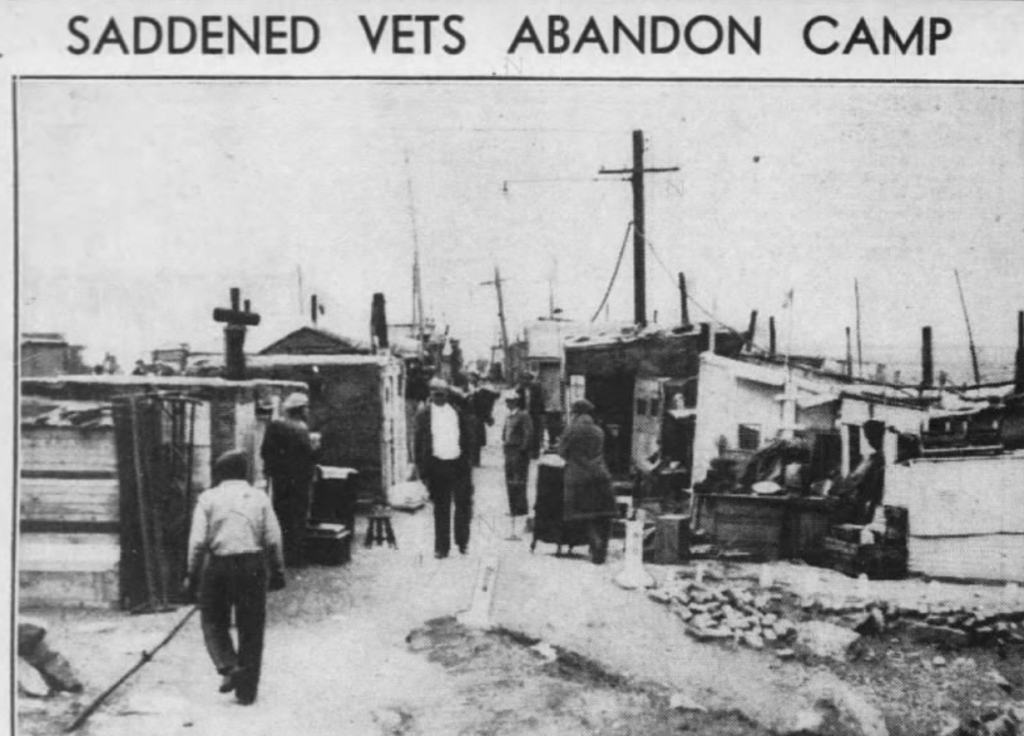

Robert Moses and the Demise of Camp Thomas Paine

In April 1934, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses ordered Camp Thomas Paine be vacated by May 1 so that the land below the New York Central railroad tracks could be improved by the Park Department. Lewis S. Davidson attempted to have the eviction postponed, or to at least obtain other unused park space for the colony in order to keep the men together.

On April 30, the Board of Aldermen passed a resolution censoring Moses for ordering the eviction. Fusionist Alderman Lambert Fairchild charged Moses with favoring “steam-shovel” government, stating that by destroying the veteran’s colony, the commissioner “was wiping out a most interesting development that has earned the approval of a distinguished neighbor and one of the best fellows in my district, Charles M. Schwab.”

Moses scoffed at the resolution, calling it “just cheap politics.” He said, “I don’t take their action seriously. How can we progress on the West Side Improvement without removing all encroachment along the river?”

Off to Camp LaGuardia at Greycourt

On May 1, 1934, 200 homeless men left in five buses from the Department of Welfare offices for Greycourt, New York. There, they would become farmers at a new city farm colony for unemployed men.

Eight of the men on these buses were former residents of Camp Thomas Paine, who had all expressed an interest in farm living. (Most of the veterans told the press that they did not apply for the colony, because they had once been white-collar professionals and were not cut out to be farmers.)

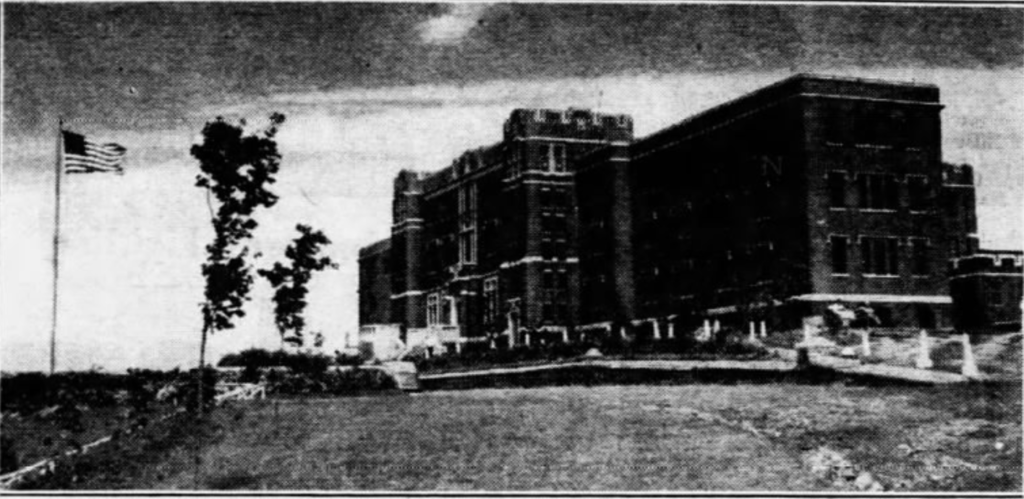

The chosen men, all between the ages of 25 and 45, would be responsible for preparing the land for the thousands of homeless and unemployed men to follow. It was expected that 500 men would be living on the farm by the end of May 1934, but the colony could accommodate over 1,000 residents.

In 1935, the city farm colony was renamed Camp LaGuardia for New York City’s Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia. It remained a shelter for the city’s homeless men for over 70 years.

Shut down in 2007 under Mayor Michael Bloomberg and purchased by Orange County for $8.2 million, the old Camp LaGuardia remains vacant. Several bidders have taken interest in the property; a team of prospective buyers recently bid $1.2 million, with plans to create a hotel, housing for artisans and athletes, and a sports dome on the 258-acre property.

For now, I will think of the veterans of Camp Thomas Paine and their pet pigs whenever I pass by the remnants of Camp LaGuardia while walking with my mom on the nearby Orange County Heritage Trail.

Thank you for telling this story, although it is so sad.

[…] create a pleasant aesthetic – roads were created and named to separate the various structures comprised of a “large garden, a mess hall with a communal kitchen and cook stove, and a rec hall with a stone […]