The horses that won prizes were real horses, horses that earn their keep and are not ashamed to do a day’s work. Automobiles run us out? Well, I guess not. Who ever saw an automobile get a blue ribbon for seventeen years service in pulling loads?”–New York Sun article about the Workhorse Parade, May 31, 1907

On May 30, 1907, nearly 1,000 work horses who carted produce and lumber and garbage and firefighting equipment and prisoners finally had their day in the sun—and a chance to shine for the people of New York City. For on this Memorial Day, they were all invited to participate in the first annual New York City Workhorse Parade.

The parade, organized by the Women’s Auxiliary of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), was based on the successful work horse parades in London and Boston, in which horses and their drivers won cash prizes and ribbons. The main purpose of the event was to incentivize owners and drivers to provide their horses with quality care and treatment. In other words, as Mrs. Minnie Cadwalader Rawles Jones noted, “to show men that it pays to treat their horses well.”

Mrs. Cadwalader Jones explained that although all work horses were invited to participate–including the teams of horses used in the fire, police, correction, and sanitation departments–the parade was intended to showcase the one-horse men, the small expressmen, the junkmen, the small market men, etc., who owned only one horse and perhaps drove it themselves. She acknowledged that these work horses were apt to be older horses that were “picked up for a song” and were often poorly treated and neglected.

The high-society ladies of the Women’s Auxiliary hoped the drivers would be anxious to keep their horses in good shape so they could win a monetary prize every year.

The Workhorse Parade

For four hours, close to 1,000 horses and their glittering, newly painted wagons rivetted the attention of 100,000 persons who packed Fifth Avenue from Washington Square to the reviewing stand at the Worth Monument at 25th Street. In the viewing stand were numerous dignitaries including Mr. and Mrs. James Speyer, Henry Bergh, Mr. and Mrs. Gordon Knox Bell, Miss Mabel Clark, Miss Marie Winthrop, Cortlandt Van Rensselaer, and other upper-crust members of the equestrian world.

Following the parade, lunch for the men and their horses was served at the ASPCA headquarters at Madison Avenue and 26th Street.

There were prizes for 47 classes, demonstrating the huge role work horses played in keeping Old New York up and running. The classes included four- and three-horse teams; brewers; lumber and box dealers; coal dealers; ice, hay and grain dealers; milk and cream men; grocers; fish and oyster men, butchers and poultry men; mineral water dealers; truckmen; confectionery men; plumbers, masons, iron and steel workers; produce; furniture; express companies; department stores; light delivery wagons; wines and liquors; laundries; paper men; and manufacturers.

More than 150 cash prizes were awarded to the drivers: $10 for first place, $5 for second, and $2.50 for third. Horses and their owners received ribbons or medals. Mrs. Ellin Prince Speyer, wife of railroad banker James Speyer and founder of the Women’s Auxiliary of the ASPCA (1906), also contributed silver medals for the winners of the classes from the city departments and the ASPCA.

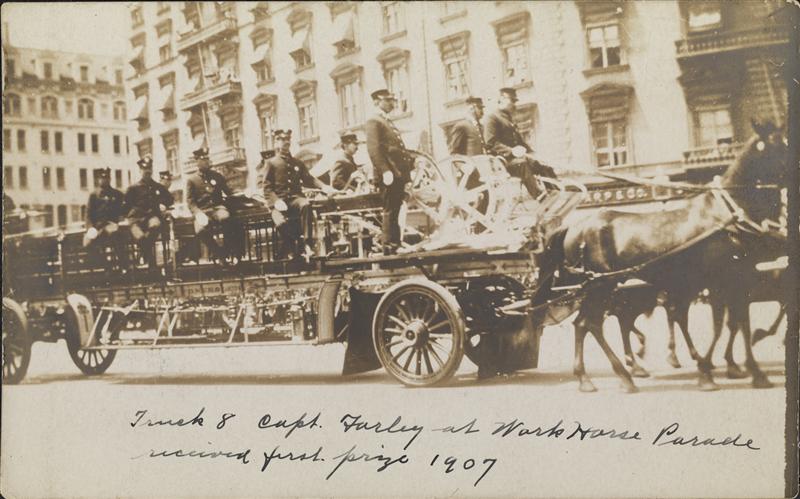

According to the New York Sun, Truck 8 Captain James J. Caberly (not Farley) took third prize (not first) at the Work Horse Parade in 1907. Museum of the City of New York

According to the New York Sun, Truck 8 Captain James J. Caberly (not Farley) took third prize (not first) at the Work Horse Parade in 1907. Museum of the City of New York

The Winning Horses

For the fire department teams, first-prize went to the horses driven by Michael V. Corbett of the tender for Engine 33, second prize went to a three-horse team driven by John Roth of Engine 33, and third prize went to Captain James J. Caberly of Truck 8 on North Moore Street.

First place among the police department horses was 17-year-old Frank, who had been in the police department for 10 years and was ridden by Patrolman John Schofield of the Traffic Squad (Frank also won again in 1914).

Traffic Squad Patrolman Otto Walsh, riding 12-year-old Shamrock, took second place (Shamrock also won a medal in 1914), and David N. Wilber took third place riding Irish Lad, the former horse of Captain George W. McClusky.

Other city department workhorses that won prizes included the horses of Edward Thompson of the Department of Correction’s “Red Maria”; Thomas Coughlin of the Bellevue ambulance (Mrs. Speyer told him that if she ever needed an ambulance, she hoped he would be the driver); John Ferguson of the Department of Street Cleaning dump cart; and John Frawley of the New York Parks Department water wagon.

There were even monetary prizes for old men and old horses. The oldest driver prize went to Abner Miller Dexter, who had driving for the United States Express Company for 49 years. Charlie, a 22-year-old truck horse at the R.E. Dietz Company stables with 17 years of service, won first prize in the old horses class. His stall mate, Eddie, who’d been pulling a wagon for 15 years, won first place in the manufacturer’s class.

The Obstacle Course

One of the highlights of the event was an obstacle course for all four-horse teams and upward, in which the men had to steer their teams in and out and around banana crates and barrels. The prize was their name engraved on a loving cup donated by Mrs. Speyer; a driver had to win the event three times in order to be able to keep the cup.

Possibly due to the lack of great prizes, only two men entered the contest in 1907. According to the New York Tribune, the contest was won by Brooklyn resident Matthew M. Sullivan, “perched on the quarterdeck of a white and gold truck of the Borden Condensed Milk Company, which looked as big as a battleship as it rumbled behind four squarely built grays that might have posed for Rosa Bonheur with full credit.”

Sullivan, described as a trim man with a waxed yellow mustache, had been with had been with the company for 21 years. Three times his horses did a “left face” and “right face” with military precision, easily maneuvering the obstacles in a slow trot and backing up to within inches of the judge’s stand. Sullivan’s horses also won a third prize in the four-in-hand class of the parade.

On the losing end was Patrick Foley, who, according to the Tribune, “tooled a brilliant red wagon of the proportions of a freight car. It bore the name of the hay and feed company of Frank J. Lennon, and was whisked about by four iron gray Normans, any one of them worthy to have borne William at Hastings.” Foley’s horses also handled the obstacles with ease, but the prize went to Sullivan because his truck was bigger and heavier, and he drove his team in a trot the whole time.

The obstacle course was all the talk among the workmen in the West Street saloons that day. As workman Marty O’Hare told the press, “It beat the Ben-Hur chariot race all hollow.”

![Work Horse Parade, [showing Anheuser Busch team], obstacle test, [New York]](https://cdn.loc.gov/service/pnp/ggbain/01900/01916r.jpg)

The Last Workhorse Parade

The last Workhorse Parade appears to have taken place in 1914. By then, the event was being sponsored by the New York Women’s League for Animals, which was founded by Mrs. Speyer in 1910 as an offshoot of the Women’s Auxiliary.

That year, life-saving medals were also awarded to several canine heroes: Trixie, a Japanese spaniel belonging to James Harcourt, received a medal for waking her mistress using her sharp little paws during a house fire. Bum, the Twelfth Precinct police dog, won a lifesaving medal for tearing off the burning clothes on a child; Great Dane police dog Jim, owned by H.T. Galpin, was awarded for saving his master’s life; and Olaf Hansen’s Newfoundland, Teddy, was recognized for saving two people from drowning in the Hudson River.