Greenwich Village in the early 1900s was home to many notable cats that made the headline news. There were the Bohemian cats led by Crazy Cat, who reigned supreme around Sheridan Square during the 1910s. And there were the more refined gentlemen cats like Old Timer, Mr. White, and Jonathan, who occupied the feline throne on Greenwich Avenue in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Old Timer

According to The Villager newspaper (June 7, 1934), Old Timer “was a gentleman adventurer type, with a touch of boulevardier.” During the late 1920s and early 1930s, he was probably the best-known cat in all of Greenwich Village.

Old Timer was not a handsome cat, per se. His nose had a large scar, his left ear was in tatters, his tail was burnt at the tip, and he had nodules on his back. But, as The Villager notes, he was a gentleman cat who got the attention he deserved.

A regular customer at Emily Burmeister’s restaurant at 56 Greenwich Avenue across from Perry Street, Old Timer would show up every night at 5:30 for his al fresco meal. As he waited to be served, he’d wash his whiskers in anticipation. Ten minutes later, Emily would leave his plate outside the front door.

The old cat’s favorite meal was meat and gravy with a bit of crackle. He always ate slowly, like a gourmet diner savoring each tasty morsel. Customers were careful to walk around him so as not to disturb his dining experience. Following his meal, he’d look in at Emily through the window, wash his whiskers again, and head off on his contented way.

Old Timer stopped coming to Emily’s restaurant in the spring of 1934. According to the reporter for The Villager, he had probably “cashed in and gone to his reward.”

Mr. White

Old Timer was not the only cat that Emily Burmeister and her partner, Anna Gasslander, cared for at their restaurant and home. The women had a long history with cats, starting with Mr. White.

Emily adopted Mr. White from a Salvation Army girl who had rescued him from an uptown speakeasy (perhaps he was one of Minnie’s many boyfriends at Jack Bleek’s Opera Cafe speakeasy?). He soon became accustomed to his “more refined environment of the Village” working as a mouser for Emily and Anna.

Mr. White did such a good job at the restaurant, he earned a month off every summer at Emily’s country home in Darien, Connecticut. Unfortunately, he was killed by a car while frolicking in the country roads.

Jonathan, the Theatrical Cat

Following the passing of Mr. White and Old Timer’s disappearance in 1934, Emily adopted a Tuxedo cat named Aloise. Emily did not think this name was suited for the cat, so she changed it to Jonathan.

According to The Villager and The Sun, Jonathan was of theatrical lineage. He was born in the magnificent Windsor Terrace (Tudor City) penthouse of Miss Alice Brady, a famous actress of stage and screen. Then he and his mother cat, Maude Adams, lived for a few months with the actor Harold Vermilyea on West 11th Street.

Jonathan did not inherit any acting talents from his early pet parents; Emily said he was more like a stage manager than a performer.

Jonathan took a lot of pride in his appearance. According to The Villager, Jonathan kept his shirt front “meticulously laundered.” The Sun said Jonathan was “immaculate in his white vest and black tuxedo, and no head waiter could be more urbane.”

In his early years on Greenwich Avenue, Jonathan spent meal times sitting on a shelf in the restaurant’s kitchen and bothering the cooks. The pestering obviously worked: By 1943, when Jonathan was 11 years old, he weighed a hefty 17 pounds.

In the 1940s, Emily and Anna operated The Emily Burmeister Restaurant at 84 Seventh Avenue in Chelsea. There, Jonathan spent almost every hour of the day on his post, which was a bench in the lobby.

Jonathan never fought with dogs or other cats (unlike the famous Tommy Cassanova Lamb of the Lambs Club), and he never returned home after a few nights out with a torn ear or damaged eye. As Emily told the reporter, the cat preferred human company to feline company.

During the few hours a day that he was not resting, Jonathan enjoyed going for walks–perhaps, as The Sun noted, “with a view of keeping down his figure.” The cat was a moderate eater, and often refused to eat if he was not served his favorite, lamb kidney, but as the news reporter said, if it were not for his walks, “he would probably resemble a prosperous alderman.”

While most city cats were always on the lookout for danger, Jonathan always had “the assured, unhurried air of a citizen who respects himself and expects others to respect him.” Even when he walked far from his home–he was often spotted as far as Fifth Avenue–Jonathan was always calm and collect.

“Jonathan can take care of himself,” Emily told the Sun reporter. “He is a wise cat.”

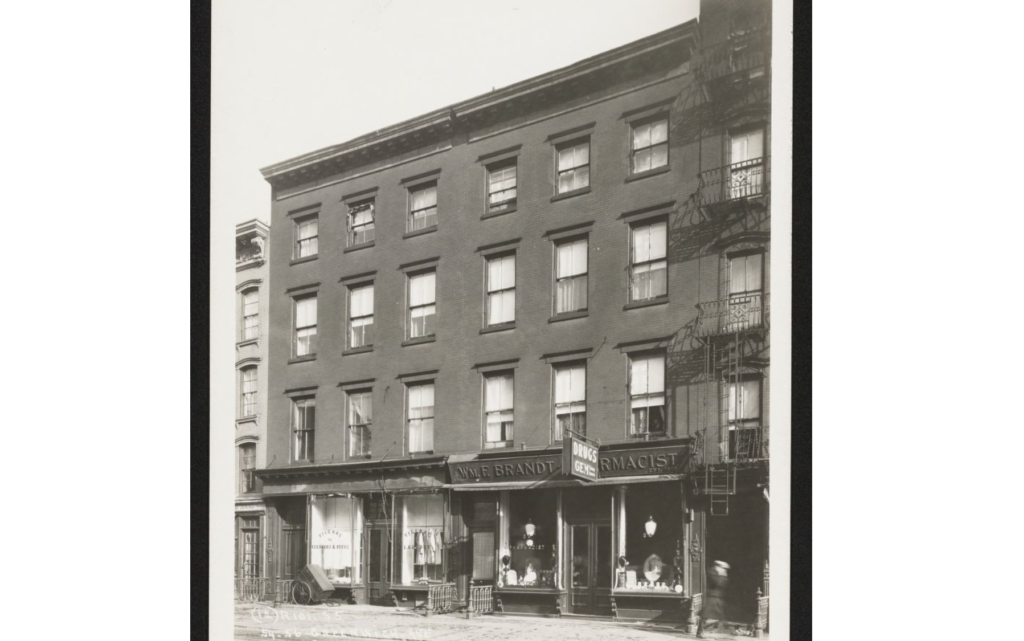

A Brief History of Greenwich Avenue

The buildings at 54-56 Greenwich Avenue, where Emily Burmeister first operated her restaurant, were built in 1861 for George Pixton Rogers. These buildings featured a basement and stores on the ground level, with apartments on the upper floors. (In the 1870s, newspaper ads boasted apartments featuring two parlors, three bedrooms, kitchen, water closet, gas and all fixtures.)

George Rogers (1789-1870) was the son of John Rogers Sr. (1749-1799), a merchant who did a booming business after the Revolution at his downtown store on Hanover Square, and at his firm of Berry & Rogers, on Pearl Street.

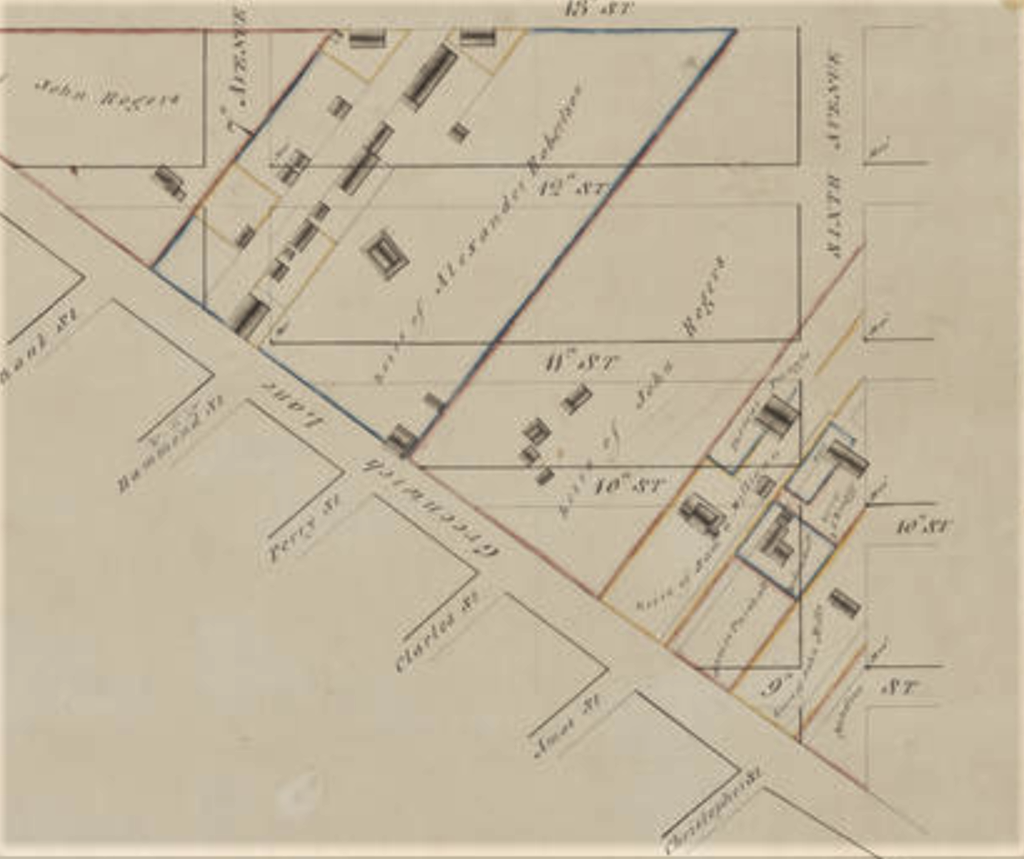

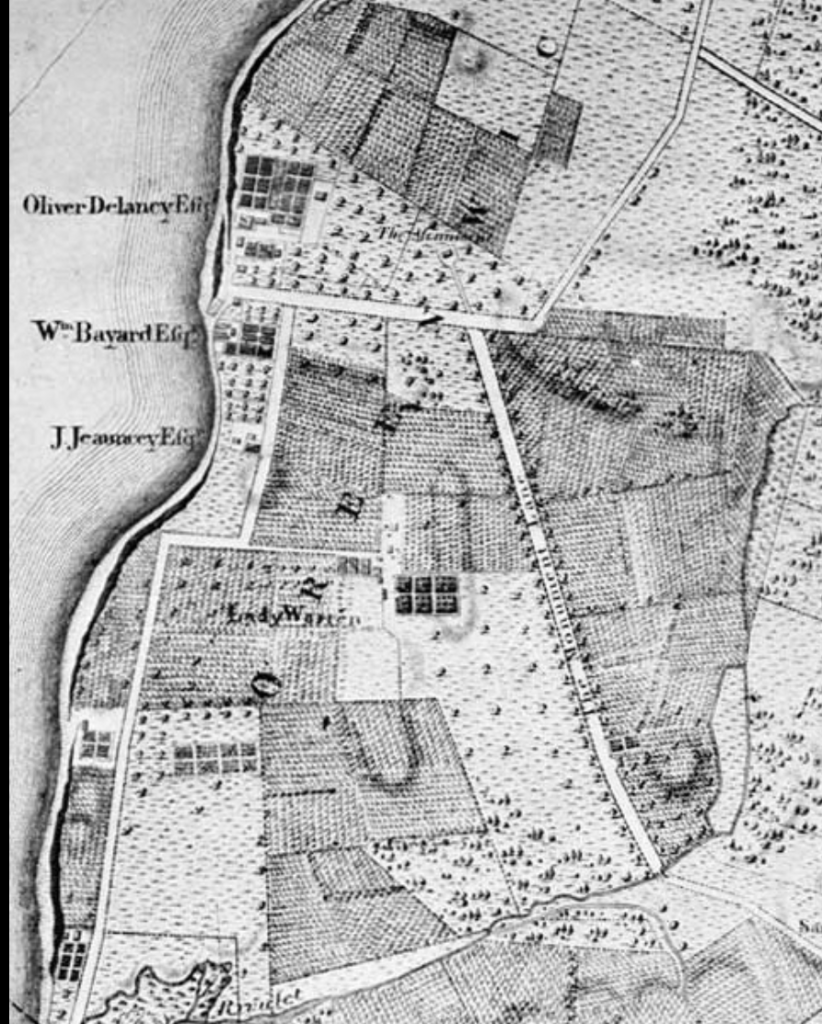

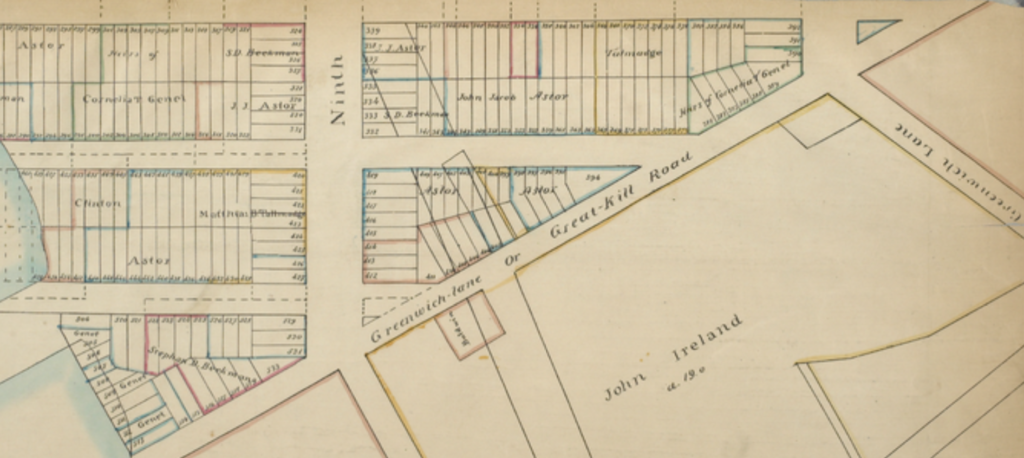

John Rogers owned several tracts of land in the Village, including two that extended from Greenwich Avenue eastward (shown in the map below). Another large tract, which extended north from present-day Washington Square, was divided in 1825 among his children, George, John Rogers, Jr., and Mary, the wife of William Christopher Rhinelander.

Greenwich Avenue is one of the oldest existing roads in Manhattan. Originally part of a Lenape trail in what was called the village of Sappokanican, it ran southeast and east to the Post Road (Road to Albany and Boston) about where Cooper Square is today.

Under Dutch rule the trail was called Strand Road. The English called it Sand Hill Road for the sandy hills that it crossed. During this time period, the road was merely a private lane that ran through several farms.

Monument Lane

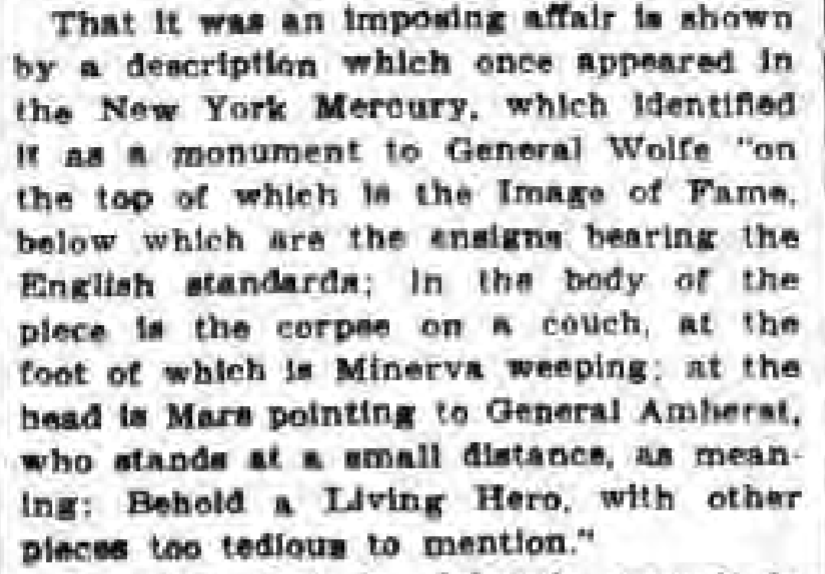

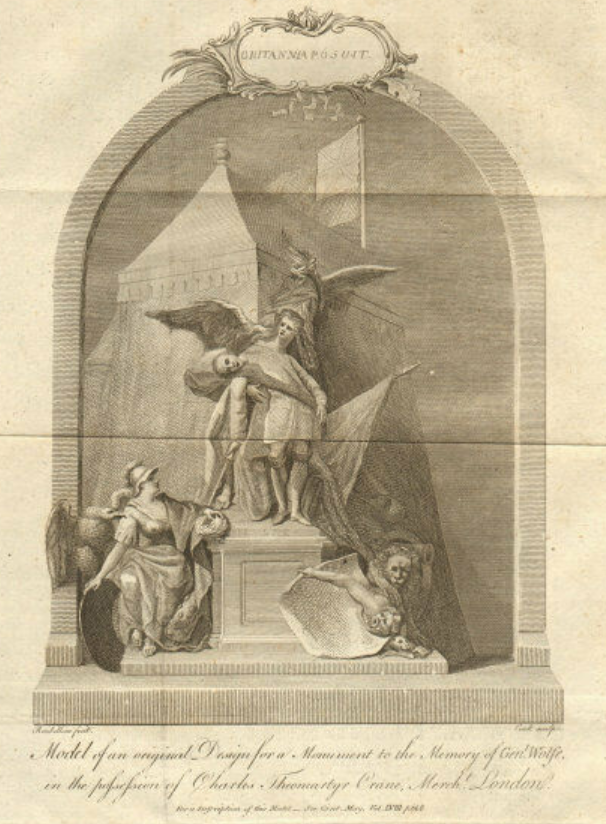

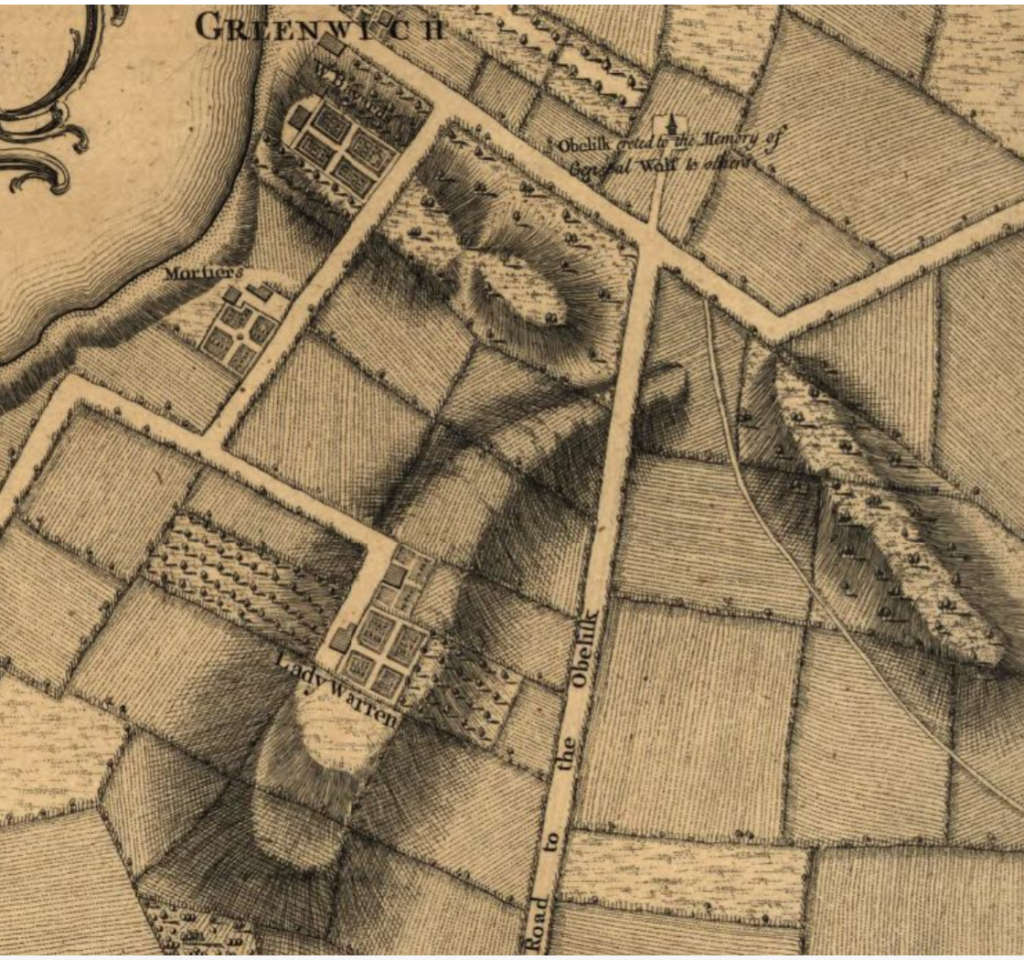

In 1762, on the spot that is now north of 14th Street where Greenwich Avenue meets Eighth Avenue, British officer William Alexander (aka Lord Stirling) erected an obelisk monument to British Major General James Wolfe, who had died in the Battle of Quebec in the Seven Years’ War. Soon thereafter, Sand Hill Road became known as “The Road to the Obelisk” or “Monument Lane.”

Aside from this description below, very little is known about the monument, and no illustrations of the obelisk exist.

According do the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society (1914):

Monument Lane began at the present Fourth Avenue and Astor Place and ran westward along the present Astor Place; thence to Washington Square North about 100 feet west of Fifth Avenue, where it crossed a brook called at various times Minetta Brook, Bestevaer’s Kill, etc.; thence to the present Sixth Avenue and Greenwich Lane; thence along the present Greenwich Lane to Eighth Avenue between Thirteenth and Fourteenth Streets, where it intersected the now obsolete Southampton Road; thence northward about 150 or 200 feet farther, where it terminated at the Monument.

Monument Lane was a favorite promenade during this time period. Gentlemen and their wives or lady friends would spend a day driving to the obelisk, and then return home via the Great Kill Road and along the old road that ran alongside the Hudson River.

The lane was officially opened to the public in 1768. At that time, the only real public road option for villagers was a waterside road that ran along the line of today’s Greenwich Street. This road, which passed over Lispenard’s Salt Meadows and Minetta Water, was often impassable following heavy rains or a strong spring tide.

By 1773, the monument had disappeared from local maps (as noted in the 1766-67 map below). Some believe that Oliver De Lancey, a loyalist, destroyed the monument when his lands were confiscated by the Americans following the war in 1783. However, based on old maps, the obelisk was probably already long gone by that time.

About 1800, the easterly part of the lane between the Bowery and the present Sixth Avenue became Art Street, a part of which survives as Astor Place between Broadway and Third Avenue. The westerly parts of the road were later named Great Kill Road (renamed Gansevoort Street in 1837) and Greenwich Lane.

In 1825, Greenwich Lane between Sixth Avenue and Broadway was closed to make way for the new Washington Square Park. Great Kill Road became Gansevoort Street in 1837, and the remainder of Greenwich Lane was renamed Greenwich Avenue in 1843.