On April 4, 1908, the members of the Junior Aero Club held a meeting on the roof of 282 Ninth Avenue near 26th Street. This six-story building was then a factory owned by pioneer balloonist Albert Leo Stevens, where he made dirigible balloons. The purpose of the meeting was “to liberate” about 200 rubber balloons and several larger balloons and small airplanes that the young boys had made from tissue paper and canvas.

One by one, the boys of the Junior Aero Club made their way up to a small iron ladder in a hatchway that led to the roof. There, they filled their balloons from a hydrogen spigot and released them into the wind. Each balloon had a small parachute with a postal card attached, announcing that everyone who retrieved a balloon was entitled to a free year’s subscription to a children’s magazine.

Pete the Cat Refuses to Fly

On this particular day, there was a cat named Pete on the roof. According to the New York Sun newspaper, Pete was “just a cat, plain cat, with no claims to distinction save the glossiest of black fur, large eyes the color of New Orleans molasses dripping in the sun and a sunny disposition–sunny when nobody attempts to flimflam him.”

I don’t know how Pete came to be on this roof, but apparently he was the pet of one of the members or organizers of the Junior Aero Club. He was also the club’s unwilling test pilot.

According to The Sun, one time the boys had decided to send Pete off in one of their miniature airplanes. “Less hep to the perils of aeronautics, Pete allowed himself to test the carrying capacity of an aeroplane and spent a most miserable half hour embracing a telephone wire until a junior scientist rescued him with a ladder.”

Now that Pete the cat was wise to their ways, he refused to fly anymore. No matter how many times the boys pet him and called out to him, “Petie, Petie, nice Petie, come on-n-n Petie,” he responded with an arched back and enlarged tail.

Many of the boys thought for sure that Pete would have responded cheerfully to all the milk and cow’s liver they had fed him in the past, but “Pete simply couldn’t see it and that ended the matter.”

Without a willing test pilot, the young boys had to resort to bricks and sticks and stones. As the Sun noted, “While the experiments were measurably successful there was a feeling that the selfish conduct of Peter left much to be desired in the way of aeronautic demonstration.”

I’m not sure if anyone was injured when the tiny airplanes loaded with bricks and stones came crashing down, but the red and blue balloons did make for quite a display. People in the upper stories of buildings near Ninth Avenue and 26th Street were especially rewarded with a colorful show.

For about two hours, the balloons zigzagged through the sky, coming to “inglorious ends against the steeples of churches, electric wires and the cornices of skyscrapers.” Many of the balloons headed out toward the Atlantic Ocean as far as the eye could see. As one old-time resident exclaimed, “Oh! It’s some more of Leo Stevens’s crazy balloon doings!”

Stevens, a member of the Junior Aero Club Advisory Board, told The New York Times he hoped some of the balloons would stay in flight for a few hours. Miss Emma Lilian Todd, the founder of the club, said she and the other advisors hoped the balloons would encourage other boys to enroll in the new club.

A Brief History of the Junior Aero Club

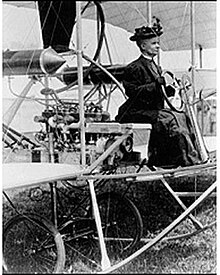

The Junior Aero Club was founded in 1908 by Emma Lilian Todd, a 43-year-old self-taught inventor and aviator who was reportedly the first woman in the world to design airplanes.

Born and schooled in Washington, D.C., Emma developed a love for mechanical devices at a young age, having been inspired by a mechanically inclined grandfather. She studied law at New York University and received a patent for a typewriter copy-holder in 1896.

Inspired by the airships she saw in London and at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Emma turned her attention to mechanical and aeronautic devices. She attracted national attention when she exhibited her first design in an aero show at Madison Square Garden in 1906.

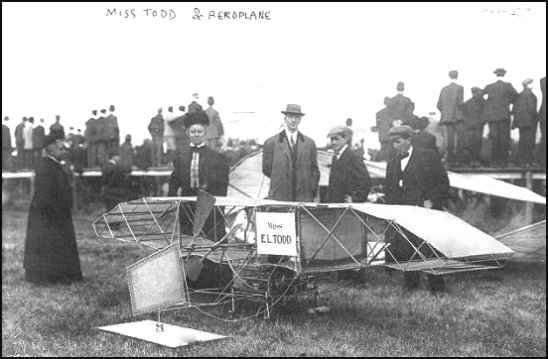

Philanthropist Olivia Sage, the widow of financier and cat lover Russell Sage, became Emma’s patron, giving her $7,000 to design and build her aircraft. Emma hired Charles and Adolph Wittemann to build the plane according to her design (the plane was built inside a large shed in Mineola, New York).

When asked about her stance on women’s voting rights in 1910, Emma replied, “I am not a suffragette…but I decided long ago that if a man can fly a woman can.”

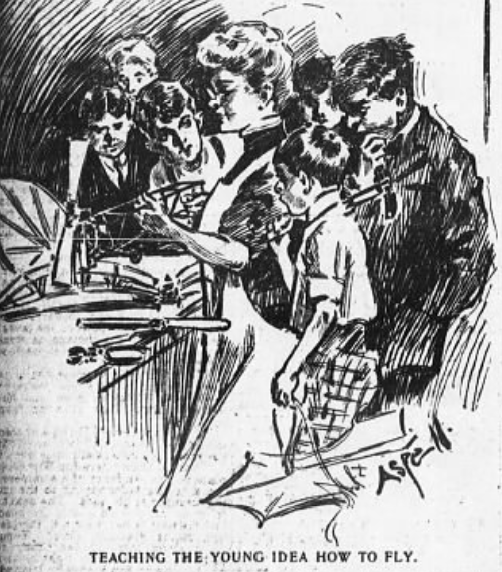

Recognizing the importance and future of aviation, Emma started the first Junior Aero Club in New York City in 1908 to educate and spark the interests of future aviators. Some of the first members included Frank King, W.E.D. Stokes, Jr., George Eltz, and Frederick Seymour.

The club held their first meeting at the YMCA on 23rd Street in March 1908. “Ballooning is the king of sports,” Emma told a reporter from the Evening World, noting it was her intention to encourage the boys to take an interest in the new sport.

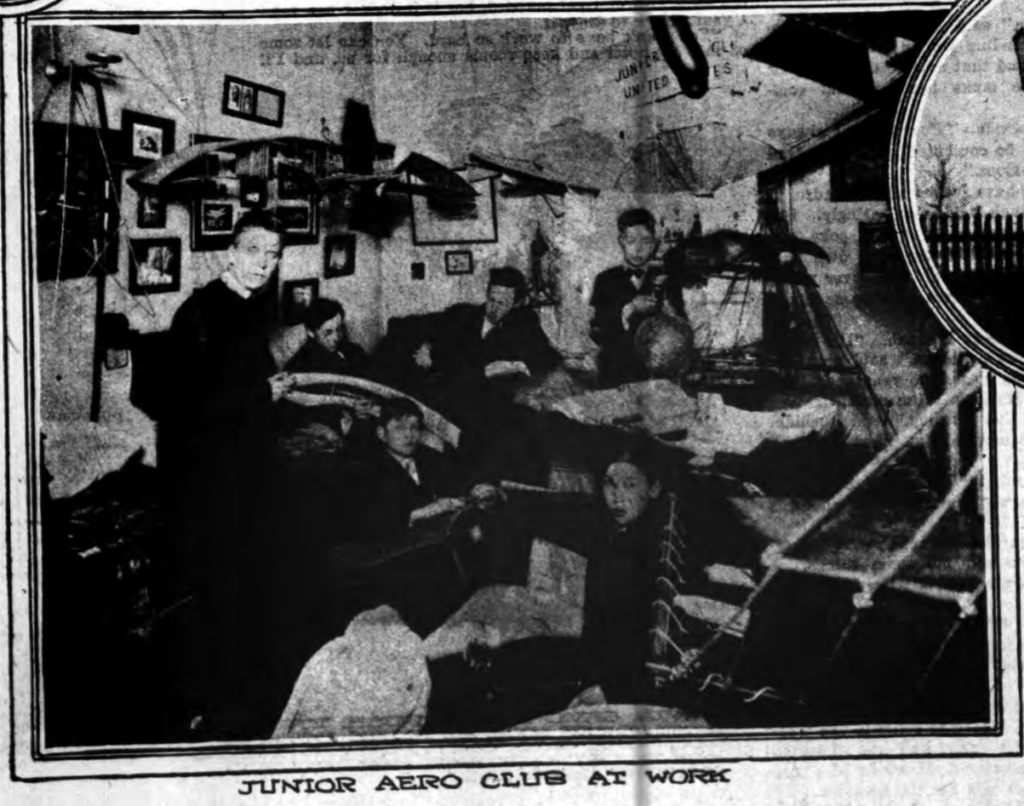

The club often met at Emma’s residence in New York–Room #19 at 131 West 23rd Street–where she had transformed her living room into a workshop. It was here among aircraft models of her own design and other mechanical toys that she instructed the boys on the science of flight and how to make models themselves.

By May 1909, the Young Aero Club had members in 11 states: New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maryland, Ohio, Illinois, Missouri, Colorado, Oregon, and Washington. By this time, Walter H. Phipps was president and Emma was no longer active in the club–she was now too busy trying to get permission from the Richmond Borough Commissioner of Public Works to fly her own plane on Staten Island (the permit was denied).

On November 7, 1910, Emma’s plane traveled 20 feet over the Hempstead Plains on Long Island (now Garden City) with a French aviator named Didier Masson at the controls. Unfortunately, the aircraft was unable to sustain flight.

The Junior Aero Club did live on, albeit, not as an aeronautics club. As it turns out, many of the members were also interested in tinkering with wireless apparatus. William Earle Dodge Stokes, who owned the famous Ansonia Hotel, called on the membership to form a new club dedicated to wireless telegraphy and telephony.

Thus, the Junior Wireless Club Limited was formed on January 2, 1909. Emma Todd was made honorary president of this new club. The other charter members included W. E. D. Stokes, Sr., W. E. D. Stokes, Jr., George Eltz, Frederick Seymour, Frank King, Professor R.A. Fessenden, and Faitoute Munn. Today, we know this club as the Radio Club of America.

By 1911, Emma Lilian Todd was working full time in Mrs. Sage’s office as her administrative assistance. Following Mrs. Sage’s death in 1920, Emma moved to Pasadena, California, where she died in 1937. Her cremated remains were buried at the Moravian Cemetery on Staten Island.

[…] Sourceshttps://hatchingcatnyc.com/2021/04/06/pete-test-pilot-cat-junior-aero-club/, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/E._Lilian_Todd, […]

Thank you, I really enjoyed seeing history come alive. 73