As soon as you have ridden, or walked—it is better to walk if there is plenty of time—beyond the fine elms of the ancient Flushing streets, you will be in as peaceful looking farming country as can be found anywhere. But the interesting thing about it is that here are seen not merely a few incongruous green patches that happen to be left between rapidly devouring suburban towns—like the fields near Woodside where the German women work—out here one rides through acre after acre of it, farm after farm, mile after mile, up hill, down hill, corn-fields, wheat-fields, stone fences, rail fences, no fences, and never a town in sight, much less anything to suggest the city.—Jesse Lynch Williams, 1902

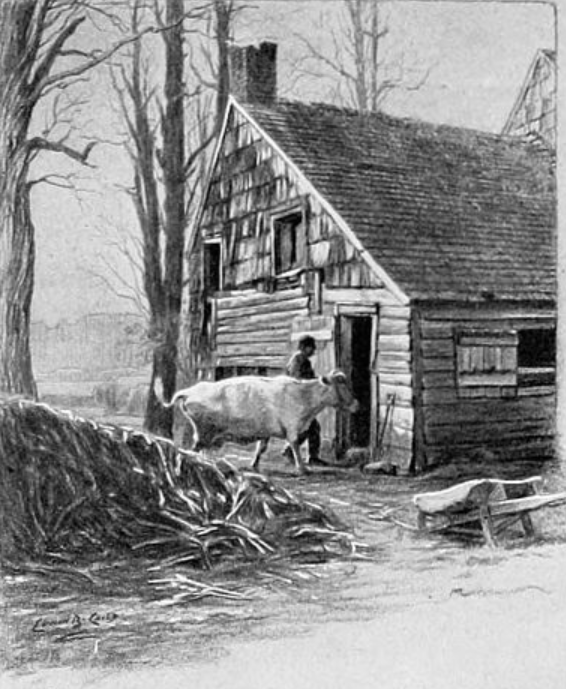

In the early 1900s, when the 250-year-old Sprong-Duryea house was already considered a decaying relic, Flushing was still flush, so to speak, with farmlands and livestock. Most farmers kept their chickens and cows outside in barns and pens. But the cow and chickens at the Sprong-Duryea homestead lived in a stable in the former drawing room, and in coops set up in the bedrooms of the old house.

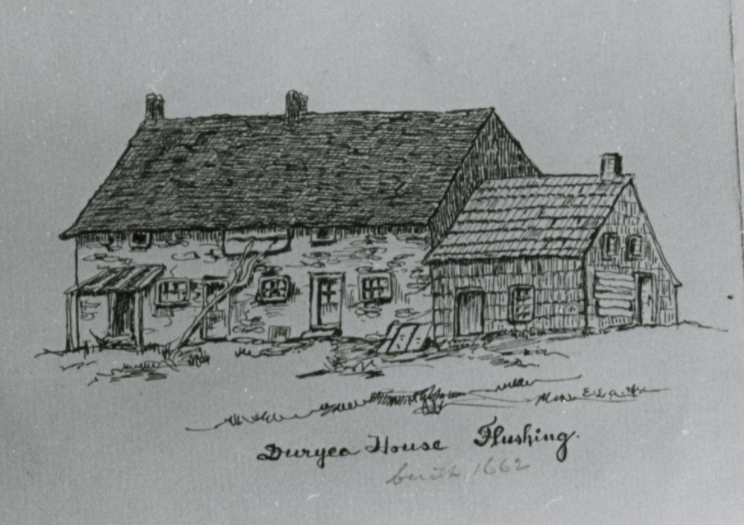

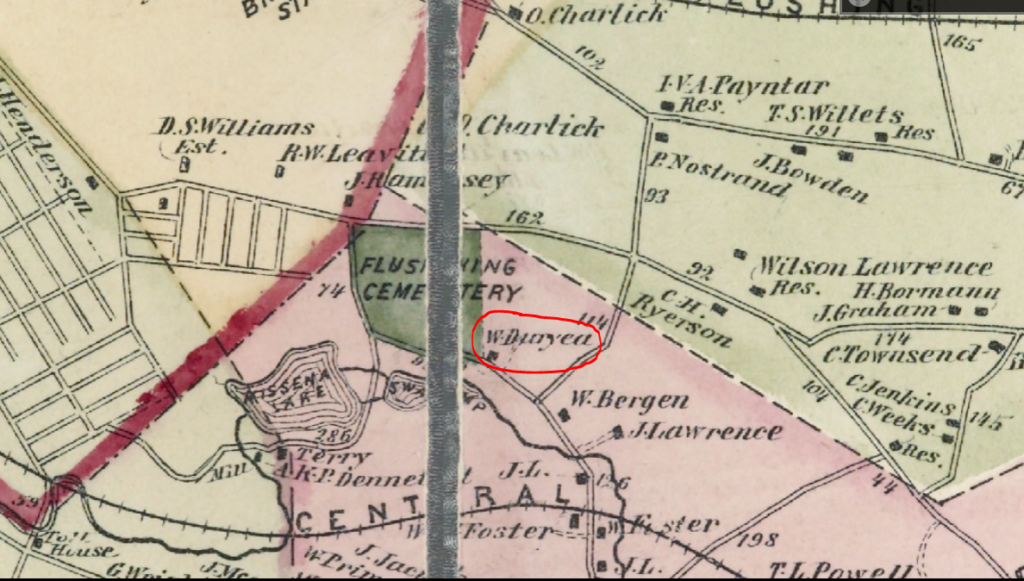

Located near the intersection of present-day Pidgeon Meadow Road and 168th Street, the old stone house was constructed in 1662 by Johannes Sprong (aka Johannis Sprungh), who came to New Amsterdam in 1660 when he was about 20 years old. One source claims Johannes came from the Town of Bonn, Drenthe, in northern Holland. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, however, states he was from Barton, England.

In either case, the young man was an enterprising pioneer who had ideas of founding a homestead far away from any type of civilization. He reportedly obtained permission from the colonial government to chose a tract of wild land southeast of the newly established village of Flushing for his homestead. There, on about 100 acres of prime rolling land, he lived and traded with the Matinecock Native Americans.

Finding an abundance of large stones on the land, Johannes built his homestead after the style of an English or Irish cottage. The walls were two feet thick of solid masonry, the small windows were set deep with broad sills and sashes that opened backward and forward on hinges, and oaken shutters could be barred from the inside. The home had 12 rooms, including several bedrooms and a kitchen with a large fireplace and bake oven.

Now that he had a homestead, Johannes set out to fill all those rooms with children. He and his wife, Anna Sodelaers of Bergen, Norway, had 10 children. One of their daughters, Annetje, married Simon Duryea in 1715. Members of the Sprong and and Duryea families would occupy the house for the next 200 years.

The Revolutionary War Period

During the Revolution, the old stone house was occupied as a fort for nearby residents. A cannon was reportedly mounted in the attic and a port hole was cut through the wall for the large gun. At one point during the war, an iron cannonball about the size of a croquet ball became imbedded in the walls.

At this time, Ida Sprong was living in the house with her family. Her husband (unknown name) was fighting with the Continental Army, so she was left alone to defend her home and family.

When the parties of marauding British became too large for her to cope with successfully by force, she pretended to side with them by sharing the stores of her household. She also allowed the Hessian officers to use the home as their headquarters while the British remained in Queens, from Whitestone to Jamaica.

One odd animal story from this time is about a Flushing farmer whose pig went missing from the pen one night. The farmer’s house was near the Hessian headquarters at the Sprong house, so he suspected the soldiers took the pig.

The farmer summoned some of his neighbors and they went into the house in search of the pig. They found the pig in bed with a solider, who told them he never dreamed anyone would come looking for the pig in his bed.

Sometime just prior to the Revolutionary War, Jacob Suydam operated a grist mill near Kissena Lake, not far from the Druyea homestead. Following his death in 1778, his son-in-law, Joseph Totten, took over the mill.

In 1803, Aaron Duryea purchased the land, which included Kissena Lake and the mill, from Joseph Totten. It was Whitehead Duryea, a son of Aaron, who was the last of the descendants to live in the old Sprong house.

Fifty years later, in 1853, the Flushing Cemetery was founded on the 20-acre farm of John Purchase, which was adjacent to the Sprong-Duryea homestead. Up until this point, John, who was a butcher in the village of Flushing, had grazed his cattle on this land.

Around 1877, the Flushing Cemetery paid Whitehead Duryea $22,000 for his land in order to expand the cemetery. Eventually, the cemetery association leased the old stone house to the Kissena Nursery Company, which had been established near Kissena Lake by Samuel Parsons in 1838.

By 1905, the old Sprong-Duryea house was being occupied by nursery worker Charles Tway and possibly other workers employed at the Kissena Nursery. (I’m not sure if the cow and chickens were still there by this time.)

With the old stone house falling into decay, nearby residents began filing complaints. The Historical Society tried to raise enough money to purchase the property from the Flushing Cemetery Corporation, but sadly, they were not able to get the funds. Sometime around 1906, the Department of Buildings ordered for the house to be demolished.