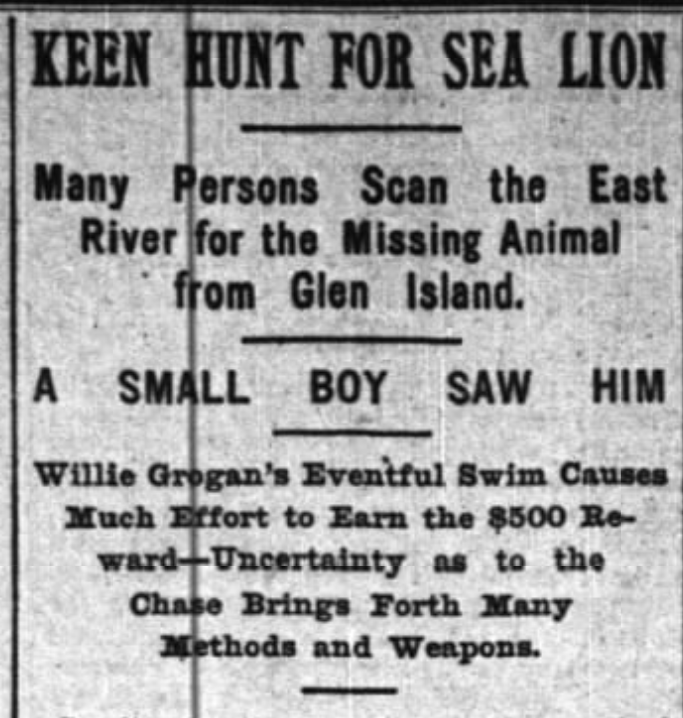

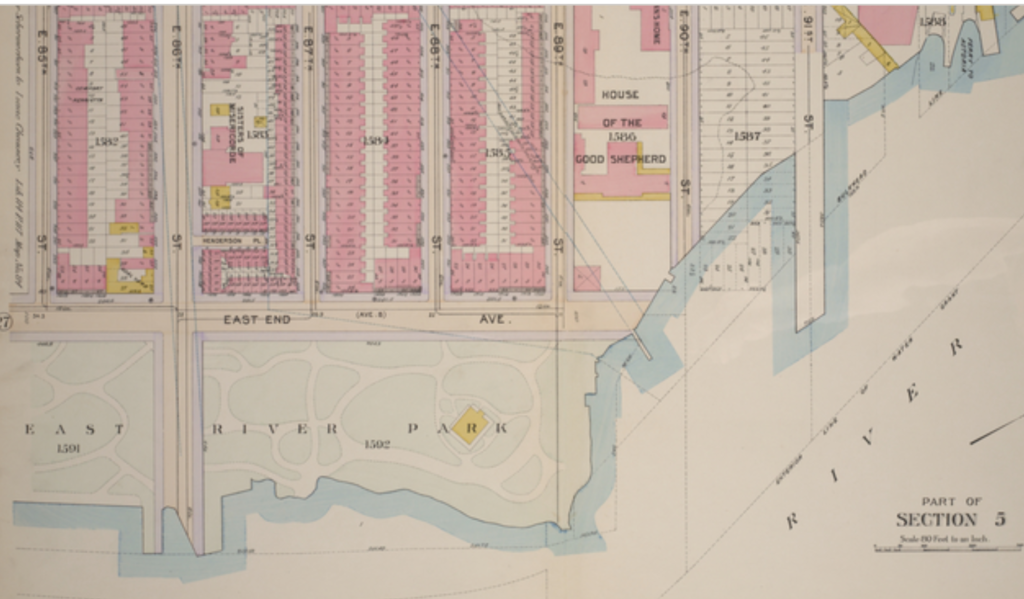

On August 12, 1897, three sea lions escaped from their enclosure at Starin’s Glen Island summer resort on the Long Island Sound. One day later, a 13-year old boy named Willie Grogan was swimming in the East River off East 84th Street when he saw what he thought was a seven-foot sea serpent–or worse–opposite East River Park (present-day Carl Schurz Park).

According to The New York Times, Willie had just surfaced from a dive when he heard what sounded like a human cough. It was dusk, so he couldn’t see that well. He wasn’t supposed to be swimming there at that time, so he feared that a police officer had spotted him from the pier.

At first, Willie thought the cough was coming from a bald man with a long, droopy mustache. Thinking it was perhaps a local German saloon keeper taking a night swim, the boy yelled out, “Hello Dutchy!” The response was another cough.

Forgetting all of his fears of getting caught by the police, the young boy started to scream as he swam back toward the pier. All he could think of were sea serpents, sharks, and Jonah the whale.

As Willie continued to yell and point at the monster, the park began to fill with people who wanted to get a glimpse of the beast. The adults in the crowd correctly surmised that the sea serpent was actually one of three sea lions that had escaped from Glen Island in New Rochelle a day earlier.

The sea lion put on a wonderful display for the crowd, alternately diving into the water and leaping high in the air. The sea lion frolicked with the tug boats and put on a show for a crowd of people on an excursion steamer.

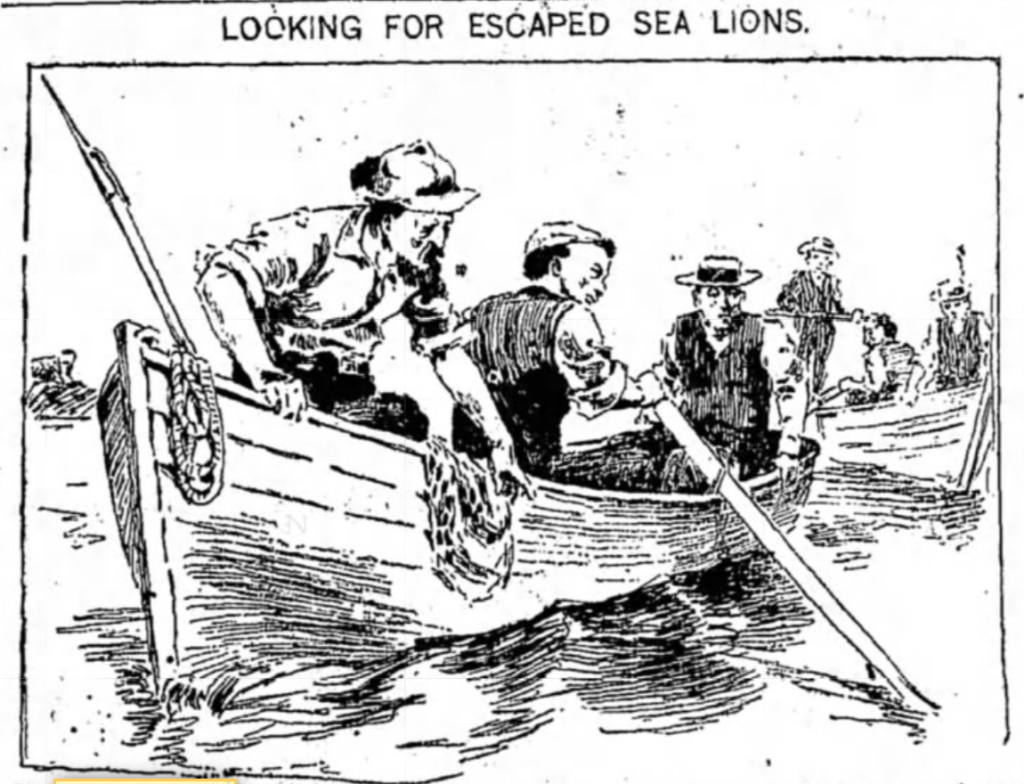

Sam McGingle and Pop Farrell got into a small rowboat and tried to capture the sea lion. They knew that John H. Starin, the owner of the pleasure park on Glen Island, was offering a $500 reward for the sea lion’s safe return.

Their boat could only hold four people, so their plan was to lasso the sea lion and tow it back to shore. Despite the large reward, the men didn’t sound all that displeased when they returned shortly thereafter to announce that the sea lion had disappeared before they could reach it.

The next day, many young boys “hunted” for the sea lion all along the East River from 80th Street to the Astoria Ferry. Armed with hooks, small brass canons, and numerous other implements unsuitable for catching a sea lion, they searched in vain for the elusive sea creature.

Alexander Barnes, a seasoned seaman from a lumber ship called the Alice Furman, organized a search party with plans to harpoon the sea lion in the flipper. Other men hunted on the piers and along the seawall around East River Park armed with nets, clubs, and even a small boat cannon.

Although the sea lion was able to elude the East River hunters, sadly, it was reportedly killed in the Hackensack River a few days later.

According to the Passaic Daily News, the sea lion was spotted near Snake Hill (aka Laurel Hill) in the Meadowlands section of Secaucus. Fisherman Dick Eaton and William O’Brien shot the poor creature after finding it asleep on the river. The poor thing never had a chance.

The Sea Lions Escape Glen Island

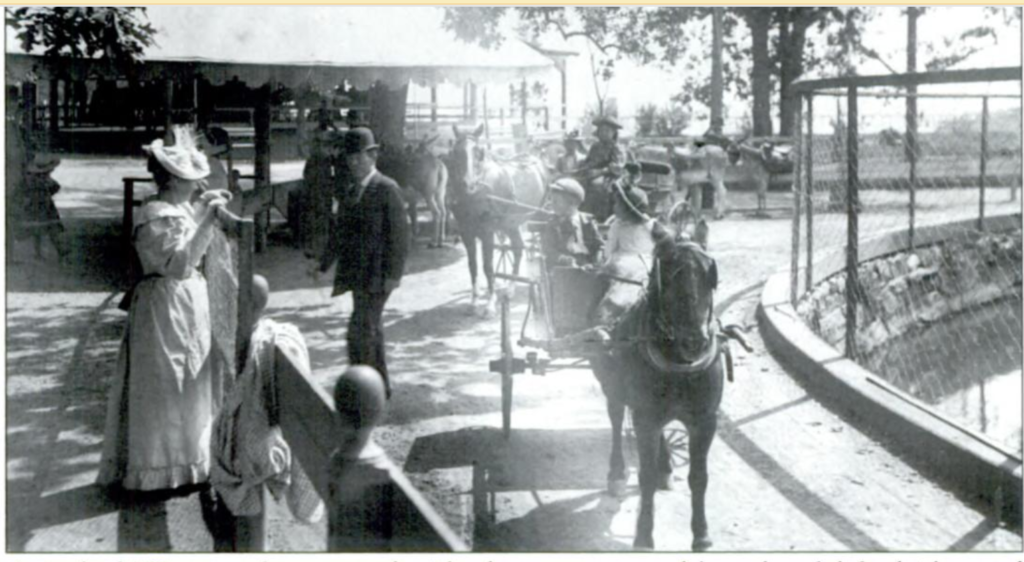

The escaped sea lion was one of 16 kept in a 100×200 foot elliptical-shaped fish pond near a bridge leading to the park’s zoological gardens. Around the man-made pond was a donkey drive, where children in little carts were pulled by donkeys.

A red rail fence kept the public off the drive. A six-foot-high wire fence at the edge of the pond separated the waters from the donkey drive and was also meant to prevent the sea lions from getting out.

According to a press agent for the park, the 16 sea lions had arrived by boat from Jersey City on August 12. They were originally from Seal Rock near San Francisco, having traveled in tanks by rail from California to New York.

On the first evening of their arrival, three of the sea lions escaped. They reportedly flopped across the dry land to another pond, and then made their way to the Long Island Sound. At the time, no one could figure out how the sea lions made their way over the six-foot fence.

Several men from the park, including Walter Bannister, superintendent of the zoo, and L.M. McCormick, curator of the park’s museum, set out in boats with nets, blankets, and poles. All they could do was watch as the three sea creatures disappeared into the Long Island Sound.

In addition to the poor sea lion that made it to the Hackensack River, one was reportedly shot and killed soon after the escape. The other sea lion was captured by way of lasso at Larchmont, just north of New Rochelle.

A week after the great sea lion hunt, a fatal tragedy led to the discovery of a small opening in the fence. It was perhaps through this hole that the three adventurous sea lions escaped.

According to the Brooklyn Standard Union, Mrs. James Crossman smuggled her pet pug, Bijou, onto Glen Island on August 21. The dog went undetected under her dress until Mrs. Crossman placed him on the ground near the donkey drive. The dog scampered under the rail fence and entered the drive, where it was in danger of getting trampled by a donkey.

One of the young boys in a donkey cart jumped out and tried to catch the dog. Bijou ran along the fence until he reached the opening. He passed through the hole, and landed in the pond, where the 13 remaining sea lions were basking in the sun on a raft.

It was mealtime. The sea lions were hungry. You can guess what happened next, so I won’t fill in the gory details.

According to Walter Bannister, the island had several valuable dogs, but they were all smart enough to stay away from the sea lions. Mrs. Crossman said she would file a lawsuit against the park to recover the value of the dog. Hopefully she never tried smuggling another dog into the park again.

A Brief History of Glen Island

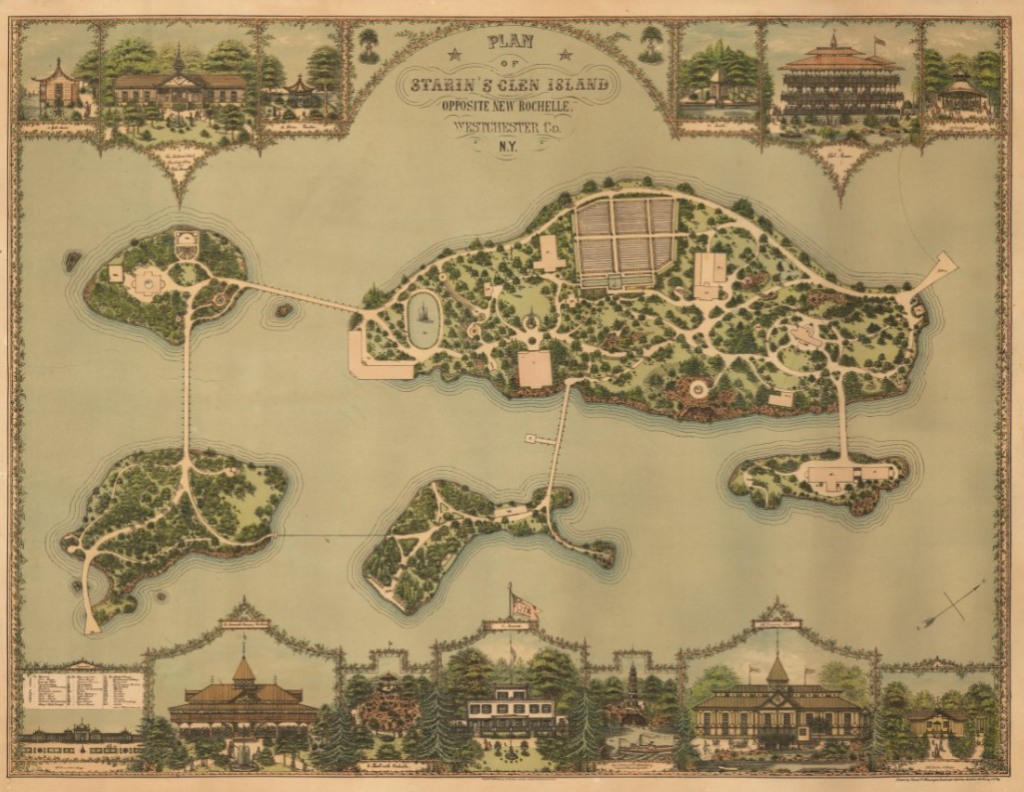

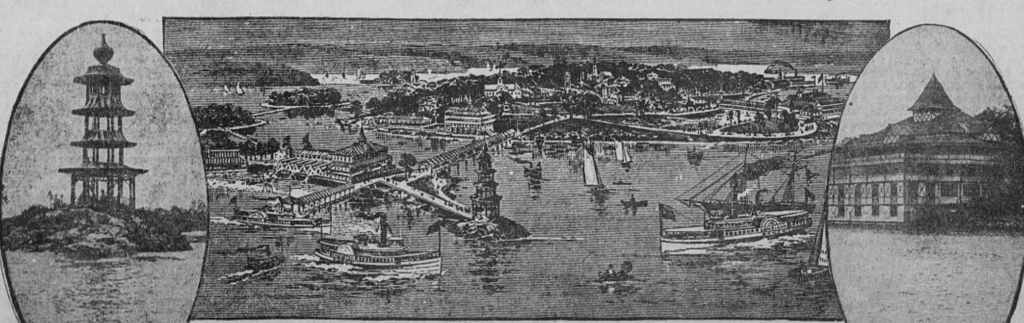

Starin’s Glen Island was a summer resort developed by U.S. Congressman John Henry Starin (1877-1881) in the late 1800s. Starin was a shipping magnate who owned a transportation company that included passenger excursion steamboats and almost every tugboat operating in New York Harbor. He developed the island as a grand destination for his excursion boats.

Although now one island, Glen Island was originally one large main island surrounded by several smaller nearby islands, rocky outcroppings, low-lying flats, and salt marshes. The first known inhabitants were the Siwanoys, whose largest village in 1640 was Poningo, located near modern-day Rye, New York.

In 1690, the island was the site of a farm owned by Jacob Theroulde, a refugee Huguenot from La Rochelle, France, who was one of the earliest settlers of New Rochelle. He sold the land to Johannes Berhuyt in 1701, who in turn gave the island to his son, Andre, in 1760.

Andre passed the island to his brother-in-law, George Cromwell, a loyalist whose active participation in events leading up to the American Revolution resulted in confiscation. In 1784, the island was sold by the Commissioners of Forfeitures.

Over the next 100 years, the island passed through several hands. At one time it was called Wooley’s Island for owner Samuel Wooley; it was later named Locust Island under the ownership of Newbury Davenport.

In 1847, Lewis Augustus DePau purchased the island and built a grand mansion surrounded by fish ponds, bathing facilities, and a bowling alley. He used the island for entertaining the rich and famous.

In 1879, Starin purchased the island for use as a country residence. A few years later, he bought four smaller surrounding islands—Glenwood, Island Wild, Beach Lawn, and Little Germany—which he incorporated into an extravagant summer resort and theme park he named Glen Island.

The enormous park, referred to as “America’s Pleasure Grounds,” was reportedly the first theme park in the country.

A total of 102 acres, the five islands were connected by red-roofed footbridges. Each island featured one of five cultures of the western world, with attractions including a Chinese pagoda, Dutch mill, and German castle (I wonder if Walt Disney got his idea for Epcot from Glen Island?).

There were also bathing beaches, music bandstands, dance pavilions, bridle paths, a miniature steam train, a theater, an aviary, and a zoo that featured monkeys, lions, camels, polar bears, elephants, and trained seals.

The park opened to the general public in 1881, attracting thousands of people each day via steamboats originating at Starin’s Dock on Cortlandt Street, or by a chain ferry and trolley cars from nearby Neptune Island. By 1887, attendance had topped one million people.

In 1904, New York’s worst maritime disaster claimed nearly 1,000 lives when the General Slocum excursion boat caught fire on the East River. Although the steamboat was not heading toward Glen Island, many people lost their appetite for taking excursion trips following the disaster. Attendance at Glen Island began to steadily drop.

John Starin died in March 1909. On January 29, 1910, The New Rochelle Pioneer reported that the Starin family had sold Glen Island to Ignatz Roth, a woolen importer, for $600,000. Over the next ten years, the resort changed hands a few times, going from one corporation to another as it gradually declined from glory days to decay.

In 1924, the Westchester County Parks Commission purchased the group of connected islands to add to its County Park System. Through extensive landfilling, all five islands were joined together to form one large island. A drawbridge was also constructed so that the island would have a permanent link to the mainland for easy public access.

Today, Glen Island Park is the second most widely used park in the County Parks system (after Rye Playland). The park offers picnic pavilions, boat launching, pathways, a catering hall, and a restaurant. Old cannons, sculptures, and several structures still remain from the days of John Starin’s resort. However, there are no longer sea lions at the park.

If you enjoyed this story, you may enjoy reading about the sea lions and penguins who swam in the fountain at Rockefeller Center.

This began as such a fun, delightful story, and ended so sadly….

As for the poor pug, it’s interesting that even more than a hundred years ago, people didn’t follow zoo rules, and ended up in tragic circumstances.

Thank you, for sharing this story. Do you have any more Glen Island stories to share? Check out the FortRoyalFoundation for another link to John H. Starin.

I am glad you enjoyed the story. I do not have any more stories about Glen Island, but thank you for the information. Perhaps I’ll come across another story from there one day while I’m doing my research.