A librarian recently asked me what makes an old news story worthy of further research and posting on my website. I told her that not only does it need to be a great animal tale, but it must also be a good people story or have ties to interesting historical buildings or events. The following story about a deaf New York Post Office cat and the deaf postal worker who loved him meets all my criteria for a fabulous animal story of Old New York. Sit back and enjoy.

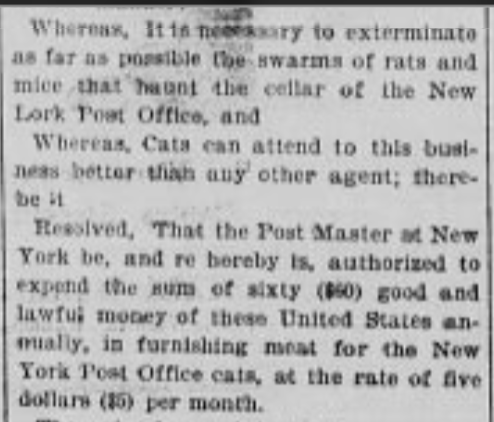

One of my favorite cat-man stories featured on my website and in my book, The Cat Men of Gotham, is about George Cook, the Superintendent of Federal Cats at New York’s General Post Office. George was responsible for feeding the dozens of New York mousers who were “employed” by the U.S. Post Office Department to kill the mice and rats that were attracted to the glue used on envelopes and packages.

When I wrote the story about George many years ago, I didn’t know then that he had a partner who helped care for the cats of the feline postal police. How excited I was to discover Gustave Fersenheim (aka Fersenheimer)!

Gustave Fersenheim was a deaf postal clerk who, according to an article in The New York Times, “was way down on the pay roll as a clerk, but whose principal self-imposed duty was to feed and preserve order among the cats in the cellar.”

In 1901, when the article was written, Gustave was 78 years old and had more than 30 years of service in the post office, having become a government employee on July 1, 1870.

At the General Post Office, his duties as a clerk were considered a side job by the numerous clerks who worked there (including, incidentally, my great-granduncle Henry Gavigan, who also worked as a clerk at New York City’s General Post Office in the early 1900s). Gustave’s main job was helping George feed the postal cats.

Gustave was an animal lover, but for some reason he tried to hide his feline feelings from his fellow employees. That meant getting to the post office very early each morning so he could attend to the cats before there were too many other workers in the building.

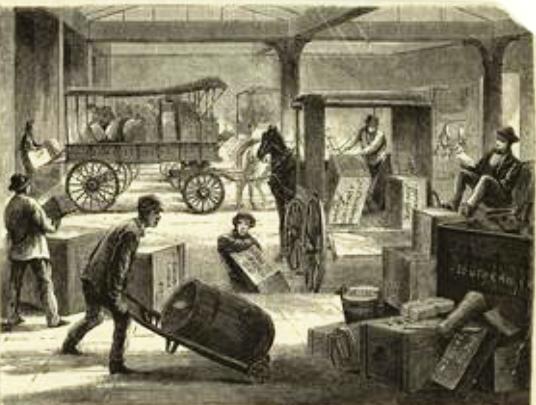

Now, Gustave lived in the South Bronx, in a third-floor apartment at 633 East 148th Street. So, every morning he would leave his home by 5 AM and make his way to the General Post Office building, which was then located in City Hall Park in lower Manhattan. That gave him enough time to feed the cats their government-rationed milk and liver from the Washington Market before he had to report for duty at 7 AM in the box delivery department.

Gustave, the son of Elias and Fredericka Fersenheim, was born in Prussia (Germany) on January 26, 1823. He arrived in New York City in 1850 and was naturalized as a U.S. citizen in 1864. He married his first wife, Elizabeth, in St. Louis, and the couple lived for a while at 84 Marcy Avenue in Brooklyn. Elizabeth died on February 18, 1895, at the age of 74.

Less than a year after Elizabeth’s passing, Gustave met a woman by chance at Dr. Thomas Gallaudet’s Church for the Deaf and Dumb at 511 West 148th Street (also then known as St. Ann’s Church for the Deaf-Mutes). As it turns out, this woman, Sarah Ann Ryer, had been Gustave’s good friend back home in Prussia.

The childless widow and widower reconnected and married at St. Ann’s Church on January 15, 1896. Gustave was 72 and Sarah was about 60 at the time of their wedding.

Gustave and the Post Office Cats

When Gustave first started working at the post office in 1873, he was about 47 years old. Since he couldn’t speak or hear, he spent much of his leisure time caressing two of the cats on the feline force. The cats grew fond of him—not only because he petted them, but because he gave them food from his lunch basket. As the number of his feline friends increased, he started bringing bigger baskets to work.

As Gustave got older and was no longer capable of doing much postal work, it was decided to move him into the cat department. He still continued to collect a salary for office clerk, but most of his time was spent caring for the postal mousers.

In addition to feeding the cats, Gustave also took measures to ensure as many kittens as possible got good homes. He could not bear to drown them, and something had to be done with the progeny of the cats, so he’d pawn them off on his coworkers. Begging his fellow workers to take kittens was reportedly the one thing the other clerks did not like about Gustave.

Tom, the Deaf Cat of the Post Office

One of the most wonderful cats on the job was Tom, a cat who, like Gustave, could not hear or speak. As one newspaper noted:

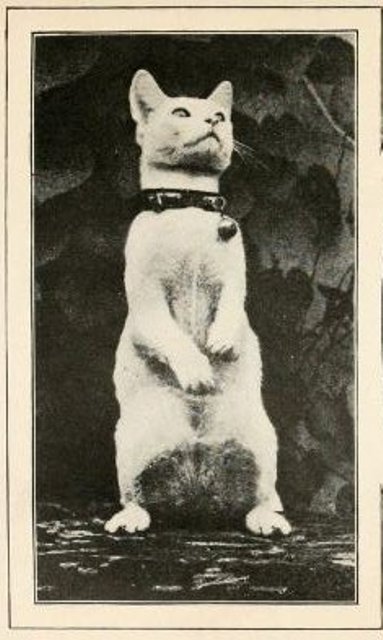

Would that all cats be like him! Voiceless he never goes out nights to howl and break the rest of hardworking citizens. He simply eats, drinks, sleeps, kills rats and makes signs.

Gustave first took Tom under his wing when he observed some of the other clerks cursing at the cat (as the newspaper noted, he couldn’t hear them cursing, but he could tell they were yelling by their facial expressions.)

As it turns out, the men were actually trying to protect Tom. While the other cats would leap and run away from the trucks bearing mail, Tom couldn’t hear the vehicles. When the men realized Tom was deaf, they resorted to tapping him or gently nudging him out of the way.

Delighted to find that Tom was a kindred spirit, Gustave adopted Tom by bringing the cat to his desk and feeding him beef. Soon, Tom followed Gustave everywhere as if he were a pet dog.

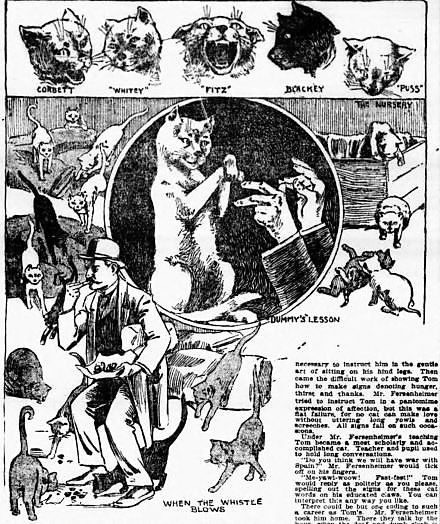

Gustave began educating Tom by first teaching him to sit up on his hind legs. Then he taught the cat how to make signs for hunger, thirst, and thanks.

Under Gustave’s tutelage, Tom became “a most scholarly and learned cat.” Eventually, man and cat began having long conversations.

“Do you think we will have war with Spain?” Gustave would ask Tom using his fingers. “Me-yawl-woo!” Tom would reply, spelling out the signs for these cat words on his “educated paw.” As the news reporter noted, you can interpret these words any way you want.

Gustave decided that Tom much preferred polite conversation to killing rats, so he took him home with him, where Tom shared the Fersenheim home with a trained parrot and dog.

The Fersenheim Parrot and Dog

Gustave and his wives were often mentioned in the Deaf-Mutes Journal, which was published in Mexico, New York, from 1874 to 1939. Not only was Gustave a trustee of the Church Mission to Deaf-Mutes and an honorary president of the German Society, he and his wives entertained often, holding parties at their home every year for their anniversaries and birthdays.

Several of the articles published in the journal referred to the Fersenheim’s parrot and dog.

The parrot, Polly, would reportedly greet Gus every night by walking up and down her perch and doing whatever she could to get his attention. The parrot could also lift one leg and twirl its claws in imitation of the deaf whenever the bell rang, which proved to be of great amusement to their guests.

According to The New York Times, one of the couple’s friends taught Polly how to say “Come in” when anyone knocked at the door. She would also fly toward the door to let Gustave and his wife know when a visitor was arriving.

In addition to the parrot, Gustave and his first wife also had a dog described as a black and tan watch dog. The dog, who spent 12 years with the couple, was able to inform his deaf master and mistress when the doorbell rang or when someone was advancing toward their apartment.

On the day of Elizabeth’s death, Gus could not find her when he returned home from the Post Office. The dog led him to the bedroom, where he found his wife lying lifeless on the floor. Her right side was paralyzed, she was blind in her right eye, and she couldn’t speak.

A doctor told Gustave that she had experienced a paralytic stroke and advised him to take her to a hospital. The first hospital refused to admit her—even though Gus offered to pay in cash—but Bellevue accepted her. According to the article, Elizabeth probably had the attack soon after Gus left for work that morning, and had lain on the floor without help all day long.

The dog, who had adored Elizabeth, refused to eat and did nothing but moan and groan in agony. Elizabeth lived for only a few weeks longer before passing away in her sleep at the hospital at the age of 74. At the time of her death, Gustave was 72, but the Deaf-Mutes Journal said he looked 15 years younger.

The Passing of Gustave Fersenheim

“There is sorrow and gloom in the hearts of the forty cats which are employed by Uncle Sam to keep rats out of the post office building.”—Pittsburgh Dispatch, August 1901

On Friday evening, August 16, 1901, Gustave became very ill. He died of gastritis two days later at his “neat and comfortable little house” on East 148th Street. Just before he died, he muttered one of the few phrases he had learned to speak: “I am done.”

Funeral services were held at his home, with Rev. Dr. Chamberlain officiating. He was buried alongside his first wife in Woodlawn Cemetery.

Following Gustave’s death, Sarah tried to give Polly to her sister, who had a pet dog named Fly. Polly and Fly became fast friends. Sadly, Polly only lived two more days after her master’s death.

Sarah’s sister put Polly in a box, which she then placed on a windowsill. When Elizabeth came to take the box, it was empty. The women found Polly in the Fly’s bed, with the dog trying to warm the dead bird.

As for the postal cats, they were also sad to lose their friend. The Pittsburgh Dispatch reported: “There is sorrow and gloom in the hearts of the forty cats which are employed by Uncle Sam to keep rats out of the post office building. Now [Gustave] is gone, and the cats, every one of which loved him, refuse to be comforted.”

Did You Know?

Gustave and Sarah Fersenheim met at St. Ann’s Church for the Deaf-Mutes on West 148th Street at Amsterdam Avenue. This church dates back to September 1850, when Rev. Thomas Gallaudet began a Bible class for deaf people in the vestry room of St. Stephen’s Church, then at the corner of Chrystie and Broome Streets.

When the congregation outgrew this facility, it was moved to 59 Bond Street. Dr. Gallaudet eventually decided to establish a new church dedicated to the deaf, leasing the chapel of New-York University on Washington Square.

St. Ann’s was incorporated into the Episcopal Church in 1854. In July 1859, the society purchased the former Christ Church and rectory, located on West 18th Street near Fifth Avenue.

In 1897, St. Ann’s Church was consolidated with St. Matthew’s Church; Dr. Gallaudet was made Rector Emeritus of the new congregation. A new chapel was constructed—the first in the country to be erected solely for the use of deaf congregants.

The Romanesque-style structure, designed by Clarence True, had a cream-colored brick exterior and could accommodate 300 people. The interior featured an inclined floor, as in a theater, so the congregation could have an unobstructed view of the altar as the clergymen prayed and preached using sign language. The church’s many windows provided extra light for those who depended on sight alone.

Today, this building houses the Manhattan Holy Tabernacle Church. Deaf services still take place at St. Ann’s Church for the Deaf, now located at 209 East 16th Street.

Incidentally, Gallaudet University in Washington, DC, the only college in the world where students live and learn using American Sign Language, was named for the Reverend’s father, Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet. His mother, Sophia Fowler Gallaudet, was a founding matron of the school.

Thank you for another moving lesson on the old New York and its cats. This was extra special for me, with the historical information on St. Ann’s Church for the Deaf.

What an amazing man and extraordinary cat (not to mention other pets)!