One of my favorite fire-cat stories of Old New York is about Peter and Chops, the beloved firefighter felines of Engine Company No. 14 in New York City’s Flatiron District.

When I wrote the story about Peter and Chops for my book, The Cat Men of Gotham, I didn’t realize that they had a canine predecessor. I recently discovered the wonderful story of Chappie, a pedigree bull terrier* coach dog who also called the Engine 14 firehouse his home.

According to The Sun, (and as Virginia knows, if you see it in The Sun it’s so), Chappie came of the best blue blood in England, having been imported to America by William Waldorf Astor, the son of John Jacob Astor III. Astor, who at one time lived in a mansion on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 33rd Street (which he razed to build the original Waldorf Hotel), reportedly presented the dog to the fire company on East 18th Street in 1889.

Everybody in the Flatiron District–or what was then called the Eighteenth Ward–knew Chappie, described as a 45-pound white bull terrier whose “ferocious looks utterly belied him.”

Chappie was especially attached to anyone wearing a fireman’s uniform, but he was also friendly with civilians. He also loved all the children in the neighborhood, who were his playmates.

The only time Chappie lost his temper was when a policeman was in sight. He could not tolerate that uniform and could tell at a glance that it did not belong to a fireman (apparently, a policeman once used his stick on Chappie, so the police were not his friends).

Chappie was very loyal to his firemen friends, though, whether he was with them at fires or guarding the firehouse. While strangers were permitted to make friendly advances outside the door, “a snarl and a gleam of ugly teeth warned against trespassing inside.”

One time, when Chappie was alone in the firehouse, Police Commissioner James J. Martin dared to come inside. Chappie did not allow Commissioner Martin to leave until the firemen returned.

According to The Sun, Chappie was “a faithful attendant” at all fires. As soon as the gongs started ringing, he would cock his ears and wait to see if he was wanted. He reportedly understood the signals and would not stir if the alarm denoted a fire outside the company’s boundaries in the Flatiron District.

When the gongs sounded a fire for Engine Company No. 14, Chappie would race around with “an absurd energy” as soon as the doors were thrown open, playfully snapping at everyone, tumbling over himself, and incessantly barking as if he were saying, “Come now, get a move on you; no time to be lost; rush her along.”

Chappie was always in his glory on his way to a fire. He would bound ahead of the galloping team, furiously barking and springing up between the horses’ legs.

Spectators would close their eyes, expecting to see him get trampled or crushed. But on most occasions, he would come racing out from under the flying hoofs and lead the procession once again, biting and barking and urging the horses on.

Once on the scene of the fire, Chappie would calm down and sit on the driver’s seat, comfortably wagging his stub of a tail as he watched his friends work. Sometimes he would bark a few times to encourage them.

During his three short years with Engine Company No. 14, Chappie sustained several injuries. He lost a piece of his tail while leading the horses, his leg was broken, and he was often bruised. But none of those injuries could stop him from doing what he loved most.

One time when Chappie was sick, the men tied him to the oaken staircase in the firehouse and rushed to the fire, thinking he was secure at home. As they rounded a corner, they heard children shouting. There was Chappie, running alongside the horses with a rope still around his neck. (The other part of the rope was still tied to the staircase.)

But then one fateful night, as the engine was responding to a box alarm at Twenty-third Street and Third Avenue, Chappie broke his paw in two places. The firemen bandaged him up and placed him on the sick list.

Determined to respond to every call even when injured, he joined the engine the following night when it responded to a fire on Broadway between Ninth and Tenth Avenues. Chappie reportedly ran to the scene on three legs.

On that call, Chappie got underneath the horses’ feet and went down. As he tried to right himself, either the pan of the engine or the pumps caught him in the back and crushed him to the pavement. The firemen cried as they carried their maimed Chappie back to the station.

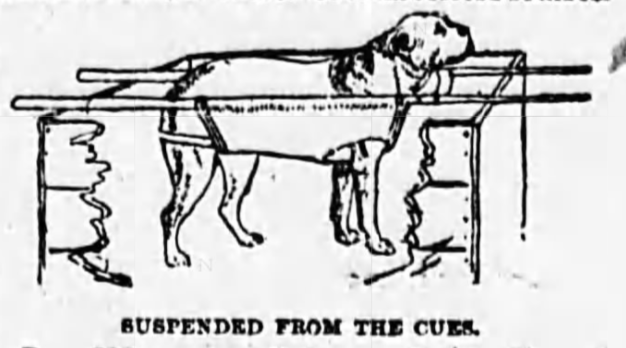

Dr. Thomas D. Sherwood, a veterinary surgeon (who was also the vet for General Daniel E. Sickles’ dog, Bo-Bo), examined Chappie and found a fractured spine, a broken leg, and several internal injuries. At first the firemen wanted to shoot the dog to put him out of his misery, but they later decided to try to save him. They rigged a canvas bandage on two billiard cues above an open dry goods box to suspend their injured fire dog.

Dr. Sherwood took great interest in the case, calling several times that day. There was a bit of hope at first, but then Chappie gave evidence that he was suffering even more in his suspended position. The men tried to make him as comfortable as possible in a pile of the horses’ straw. They also gave him some opiates to help ease the pain.

Chappie died in his firehouse home at 2 a.m. on March 23, 1892. Shortly after his death, Peter and Chops took over as mascots of Engine Company Number 14.

A Brief History of the Flatiron District and Engine Company No. 14

The Flatiron district, which is roughly bounded by Seventh Avenue and Park Avenue from 14th to 30th streets, is named for the iconic Flatiron Building, constructed in 1902 on the wedge-shaped intersection of Fifth Avenue and Broadway. In the early 19th century, before there was a Flatiron Building (and the narrow buildings that preceded it), the district was mostly open pastures owned by farmers such as Isaac Varian, Casper Samler, and John Horn.

Isaac Varian was born in New York City on September 8, 1740. He was a butcher for a long period, residing and doing business at 176-180 Bowery from 1806 to 1818. He was married three times and had 16 children. In his spare time, Varian established a farm and homestead on a 25-acre plot he purchased from John Horne sometime during the 1780s.

The homestead stood on 26th Street just west of the Bloomingdale Road (Broadway), and was home to at least two generations of Varians until it was demolished in 1850 to make way for new townhouses. Ten years after Varian’s death on May 29, 1820, the many heirs to his estate began selling off their allotted parcels to individual buyers and speculators. One of those parcels on 18th Street was eventually conveyed to a man named John L. Gross.

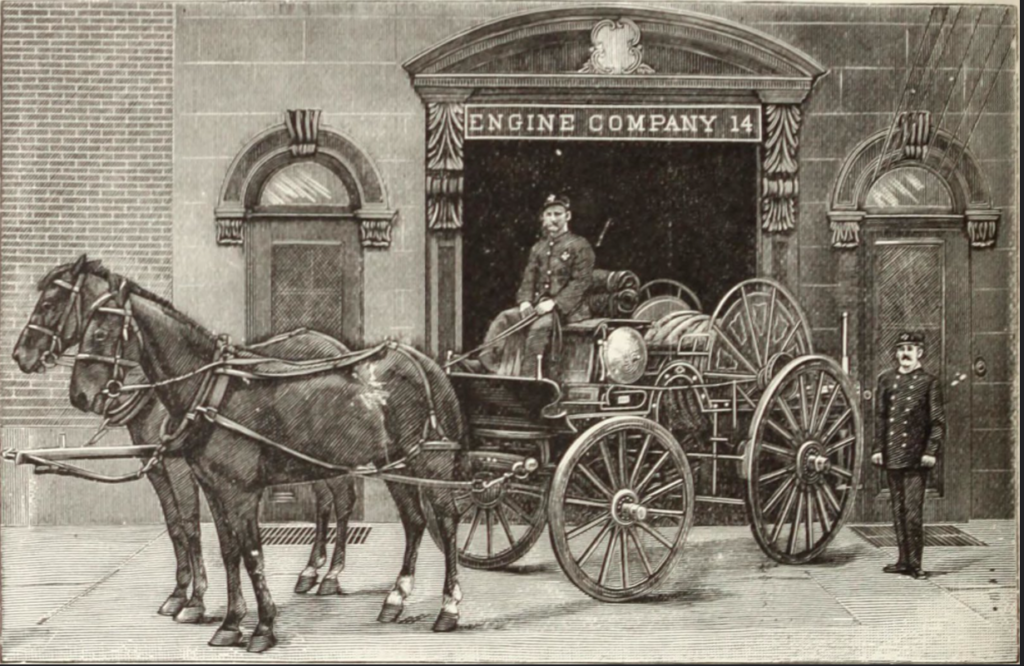

On December 30, 1861, Gross sold his house at 14 East 18th Street to the city for $7,825. Two years later, the Metamora Hose Company No. 29 (organized in 1854) relocated from 21st Street and Broadway to their new firehouse on East 18th Street. Four years later, on October 6, 1865, a new engine company called the Metropolitan Steam-Engine Company No. 14 was created to replace the old volunteer hose company.

In 1894, two years after the passing of Chappie, Napoleon LeBrun & Son was tasked with designing a new firehouse at 14 East 18th Street.

Featuring Corinthian columns on the third floor that support decorative arches over the windows and large terra cotta medallions that pronounce the date of construction, the firehouse is what the AIA Guide to New York City describes as “A delicate Italian Renaissance town house for fire engines.”

The structure is still as beautiful today as it was during the days of Chappie, Chops, and Peter, albeit the still-active firehouse is no longer home to horses, coach dogs, or fire cats.

*The Sun said Chappie was a bull terrier, and The Evening World called him a bulldog, but the illustration looks more like a pit bull.

Poor Chappie! I’m glad he was at least very much loved in his life, and very happy. My grandfather was a firefighter in nearby Newark and one of the stories that’s been handed down is that when rushing to a fire, his company’s truck hit and killed the fire station’s dalmation. So it seems like maybe accidents like these were fairly common for firehouse dogs. Poor things….