“The barking of two dogs, answering each other on the wind and sleet swept East River saved the lives of more than 80 men, women and children asleep in the cabins of a line of 40 coal barges, torn from their moorings, at the foot of East 96th Street.”–New York Daily News, December 27, 1926

The Winter Refugees of New York

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, a city-full of people formed close-knit communities along New York City’s waterfront in wintertime. They did not live in the city proper, but rather in small cabins on coal barges moored at various docks in Manhattan and Brooklyn.

Throughout the spring, summer, and fall, these coal barges dotted the Great Lakes and large rivers. But at the first signs of winter, the boat captains would go in search of a safe haven for their boats and their families who lived on board with them.

The hundreds of men, women, and children who spent the winters on their coal boats in Brooklyn and Manhattan were called the winter refugees of New York.

The Makings of a Disaster on East 96th Street

In the winter of 1926-27, a fleet of 30 to 40 coal barges laden with 50,000 tons of coal were moored together and anchored for the season at the foot of East 96th Street. The docks at 96th Street were the landing place for all barges with coal or merchandise destined for upper Manhattan and the Bronx.

Approximately 60 or more men, women, and children made up this small community of winter refugees. They spent the first day in their new home for the winter on Christmas Eve.

That winter the fleet comprised two lead boats: the J.J. Reynolds, led by Captain Jim MacLennon, and the R.T. Davies, with Captain Fred Graves at the helm. Behind them, lashed together three abreast, were the other barges.

On Christmas day, the families dressed in their best and gathered for holiday celebrations. Several dogs, including Fanny of the R.T. Davies, Sandy of the barge J.J. Reynolds, and Peggy of the New York City fireboat George B. McClennan (docked at East 99th Street), shared friendly back-and-forth banter throughout the festive day.

But that night there was a sleet storm accompanied by 50-mile-an-hour gale winds. While the winter refugees were sleeping in their cabins, the moorings that tied the fleet together and held the clump of canal boats to the shore slipped. As on newspaper noted, “So suddenly and without sudden motion did this occur, that not a soul on board of any of the barges was awakened.”

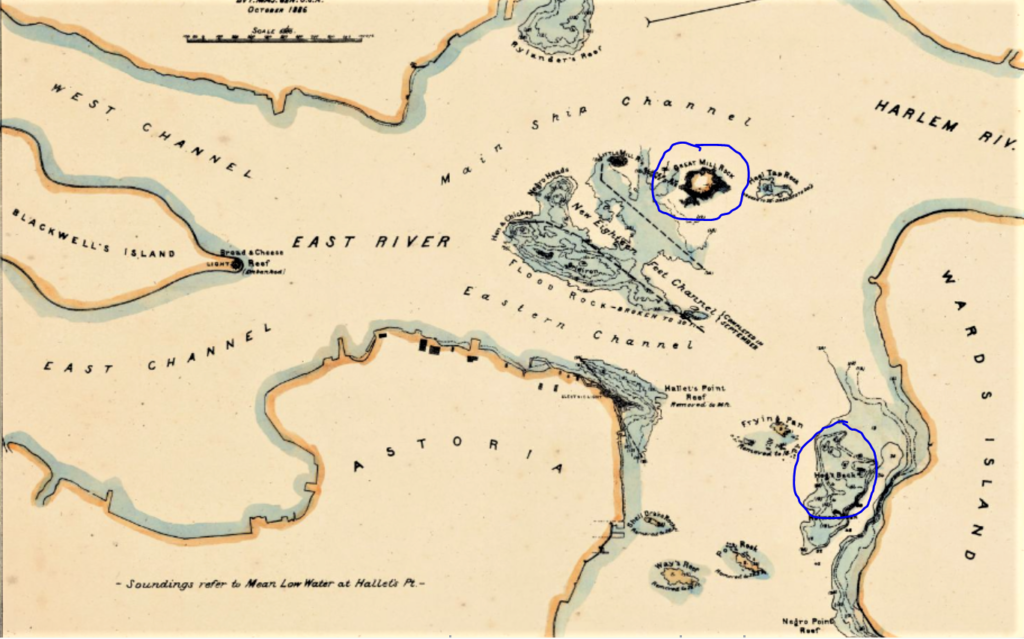

The tide and cross-currents at this point in the East River are perilously strong and tricky–that’s why sailors have called it Hell Gate. With the detached fleet of barges caught up in the surge, a tragedy was in the making. One ounce of bad luck could have meant sudden death for the sleeping families.

Only a week earlier, the wreck of the motor launch Linseed King, which happened in the icy waters of the East River only moments after the boat left the 96th Street pier, killed 33 men. The tragedy was still on the minds of the canal men wintering on the pier…

Fortunately for the winter refugees on late Christmas night, there were two occupants in the colony who were wide awake: Fanny, a cross-breed Airdale and shepherd, and Sandy, a cross between an Airdale and an Alaskan husky dog.

When the boats broke loose, Sandy sank his teeth into the bedclothes of Captain MacLennon, who was sleeping on his bunk. The large husky showed his fangs and growled. Fanny went onto the boat deck and started barking and growling as the barges began heading east toward the nearby Hogsback Reef and the rocks of Hell Gate.

A Miracle on East 99th Street

Three blocks away, the city fireboat George B. McClellan was tied up at the foot of 99th Street. Fire Lieutenant John Hughes and his crew of 16 men were below deck. All cuddled up on an old coat on a bench in the McClellan’s cabin was Peggy, a fluffy white spitz dog who served as mascot–not watchdog–of the fireboat.

Hearing Fanny’s barks for help, Peggy awoke from her snooze and sprang from her comfy bed. She leaped through a partly open hatch and landed on the boat’s icy deck.

Looking out through the darkness, the little dog began to answer Fanny’s staccato yelps for help on the R.T. Davies. Barking at the top of her lungs, Peggy aroused Lt. Hughes and the other sleeping men. They knew that something must have been very wrong for their mascot to be barking as if she were being murdered.

Lt. Hughes was the first to respond to Peggy’s barks. At the sight of him, Peggy doubled her efforts, changing her barks to deafening howls as she made sure she faced in the direction of the danger.

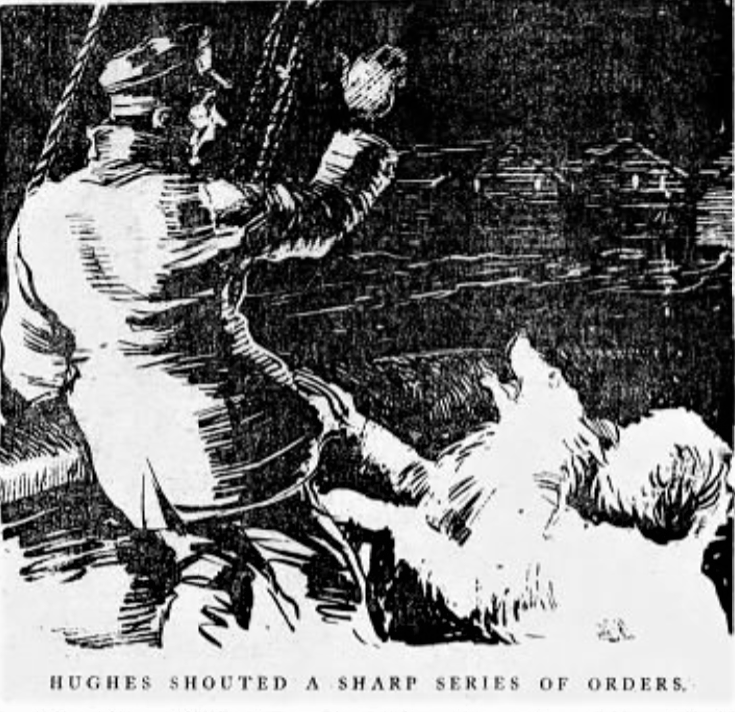

Lt. Hughes leaned over the gunwale and aimed his light at a ghostlike fleet of barges drifting toward the treacherous rocks and currents of Hell Gate.

On the canal barge R.T. Davies, Captain Frederick Graves began shouting along with Fanny’s howls for help. Half dressed, the members of the coal barge families ran from their cabins and joined in the barking and shouting. Soon, the winter refugees heard the long shrill blast of the fireboat, followed by many short blasts summoning other ships for help.

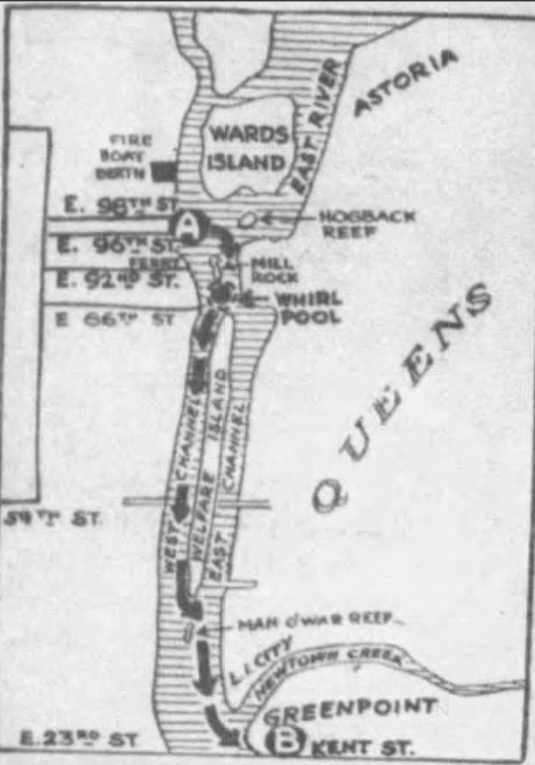

Back on the McClellan fireboat, two pilots were posted at the wheel and ready for action. A line was thrown to the foremost barge just as the cluster of boats moved swiftly toward Hogsback Reef and the piers of Hell Gate Bridge.

Using clever maneuvering and full power, Lt. Hughes attempted to herd the boats and head them off Mill Rock into the center of the stream. But the fireboat was no match for coal-laden barges.

Within minutes, the tugboat Frank A. Furst, under the command of Captain John Jones, responded to the fireboat’s distress signal. The tug and the fireboat put their noses against the J.J. Reynolds and, through combined effort, were able to push the large, heavy mass away from Mill Rock, the whirlpool, and the upper end of Welfare Island (previously called Blackwell’s Island and now known as Roosevelt Island).

Despite the gale winds, Lt. Hughes managed to fasten a line to the Reynolds. The tugboat steamed down river toward the end of the runaway barges and tossed a line onto another barge to secure that end.

Through the western channel between Welfare Island and Man-of-War reef, the fireboat and tug maneuvered the heavy boats in the wind-freshened currents. It was not until the coal barges reached the lower end of Welfare Island that the heavy mass was under control.

Once the caravan reached the Brooklyn shore, a U.S. dredge with a crew of three men was added to the rescue party. At approximately 8 a.m., the barges were finally tied down to the American Export line’s pier at the foot of Kent Street, Greenpoint, as well as along the Newtown Creek.

Once they were safely tied up, the fireboat and tug were ready to take the women and children ashore. But the families didn’t want to leave the barges. They put on warm clothes and drank coffee in the cabins while offering Peggy “choice dainties from their galley cupboards.”

Many of the barge captains thanked their human rescuers for saving them in the nick of time. Some folk offered a prayer of gratitude for Peggy for responding to Fanny’s howls for help.

Fanny and Sandy were rewarded by their barge families with juicy chunks of steak, but it was Peggy who received the most praise in all of New York. She had proven that a mascot can truly deliver good luck.

Did You Know?

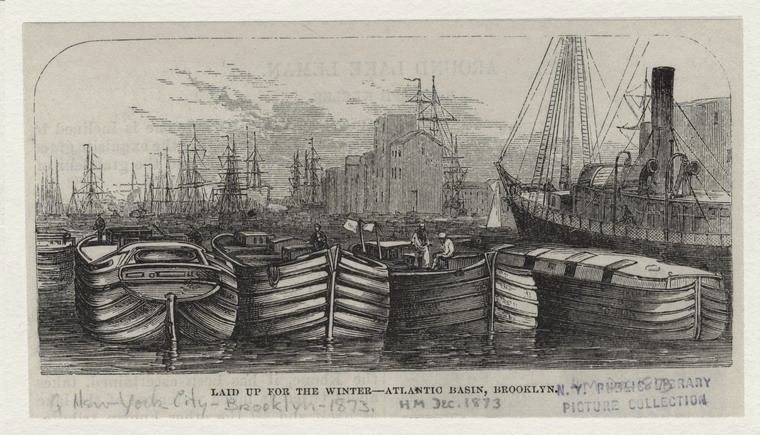

Some of the largest colonies of winter refugees were located in Brooklyn’s Erie Basin and Atlantic Basin, but there were also several communities in Manhattan.

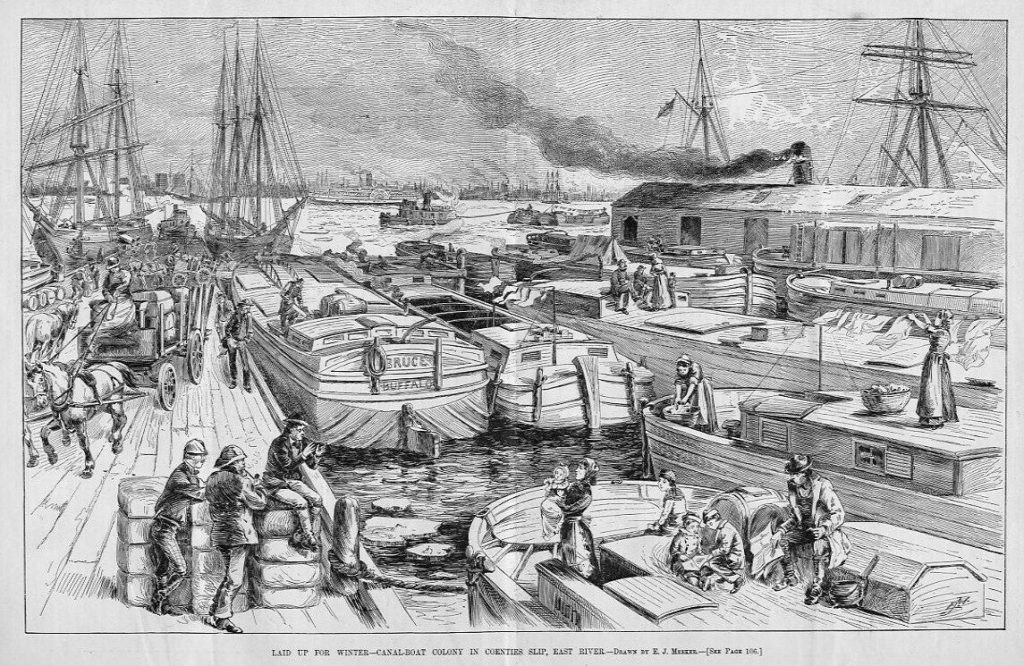

In addition to the colony at 96th Street, there was also a small barge community at the foot of 33rd Street on the Hudson River and at Coenties Slip, an artificially created berth in lower Manhattan for ships and other vessels.

As one newspaper noted in 1905, “A merrier, happier colony is not to be found in New York than the tenants of the cabins of the canal boats.” The cabins were tiny but tidy; most were divided into two rooms: a kitchen with a cooking range and a general living room that served as parlor, sitting room, library, and bedroom.

The piers were their Main Street, where the canalers would stroll and catch up on the latest news and gossip with their neighbors. The barge decks served as yards for the children and dogs, and for hanging the clothes out to dry on wash day.

The winter refugees made the most of their unique living conditions, and in fact may have had more of a social life than those living ashore in traditional homes.

The adults enjoyed nightly dances, card parties, live theater, and poetry readings, oftentimes dedicating an empty canal boat for use as a community center for social activities. During the day, the women could go shopping at the department stores and have purchases delivered to their cabin door. The butcher, iceman, and baker called for morning orders, and the children attended public schools.

The Trinity Church Corporation even provided a reading room and library for the winter refugees at Coenties Slip.

One big drawback: There was no running water, so the men would have to haul five or six pails of water a day from distant faucets for cooking and washing. (The barge residents only took baths in the summer, when they could bathe in the rivers.) They also had to rely on oil lamps for light and large coal stoves for heat.

In addition to those who lived on coal barges, there were two other distinct groups of winter refugees who sought shelter in the New York Harbor. Those who hauled grain along the Erie Canal were called Westerners. Those who hauled agricultural products from New England and Canada were Northerners.

The Westerners had a raised cabin in the bow of the boat to keep their horses, which were used when the boats were “walked” from Albany to Buffalo (note the horse in the illustration above). In the winter, they would loan their horses to New York State farmers. The Northern men wintered their horses at their headquarter stables in Troy, New York.

The Last of the Winter Refugees

By the 1940s, there were only a few dozen or so winter refugees who hunkered down in the New York Harbor when the New York State Barge Canal shut down for the season. The men were now leaving their wives and children at home during the winter months, returning home themselves on weekends and holidays.

For those families who stayed together in the winter, poverty was often the reason for living in the small floating communities (they could not afford to rent a home on shore). But these families tended to keep to themselves–gone were the glory days of community centers and gatherings and children romping on boat decks with their pet dogs.

Very interesting, as always. Thank you!

Good dogs, very good dogs, probably a cat cut the barges loose. LoL