Over the River and Through the Woods to Gabe Case’s Place on Jerome Avenue

As I sit here writing this story on the third day of January 2022, we still have not had any snow in the Hudson Valley. Well, we had a dusting of snow on Christmas Eve, but that was certainly not enough snow to go sleigh riding on a plastic toboggan let alone a horse-drawn sleigh.

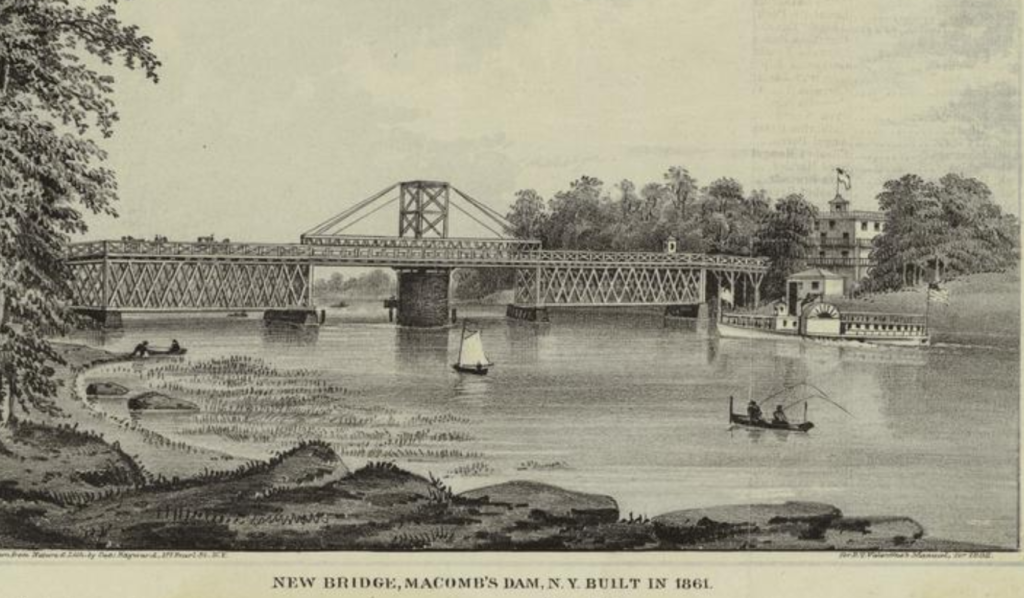

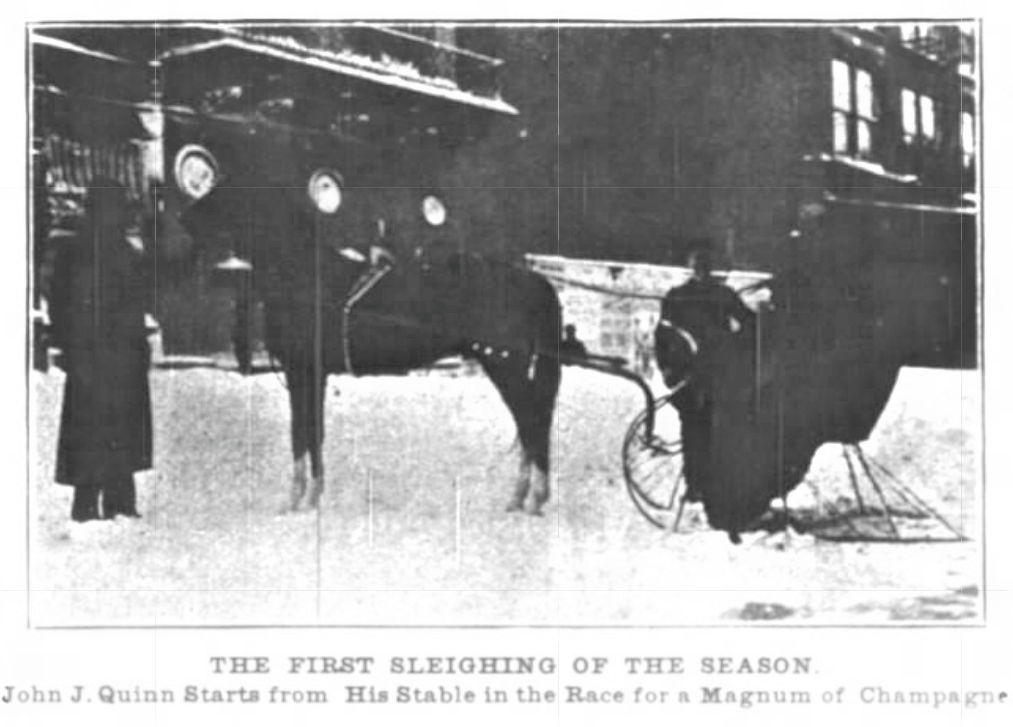

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the first snowfall of the season in New York City was marked by a race in horse-drawn sleighs. Trotters of wealthy railroad men, bankers, merchants, and stablemen would race through Central Park, down Seventh Avenue, over the Central Bridge (Macombs Dam Bridge), and along Central Avenue (Jerome Avenue) to Johnny D. Barry’s, Gabe Case’s, or Judge Smith’s roadhouses in what was then the West Morrisania neighborhood of the Bronx.

The prize to the horseman who arrived first on runners without scraping the macadam was a magnum of wine or champagne, plus plenty of bragging rights. It was expected that the winner would share the magnum’s contents with his fellow horsemen at the roadhouse.

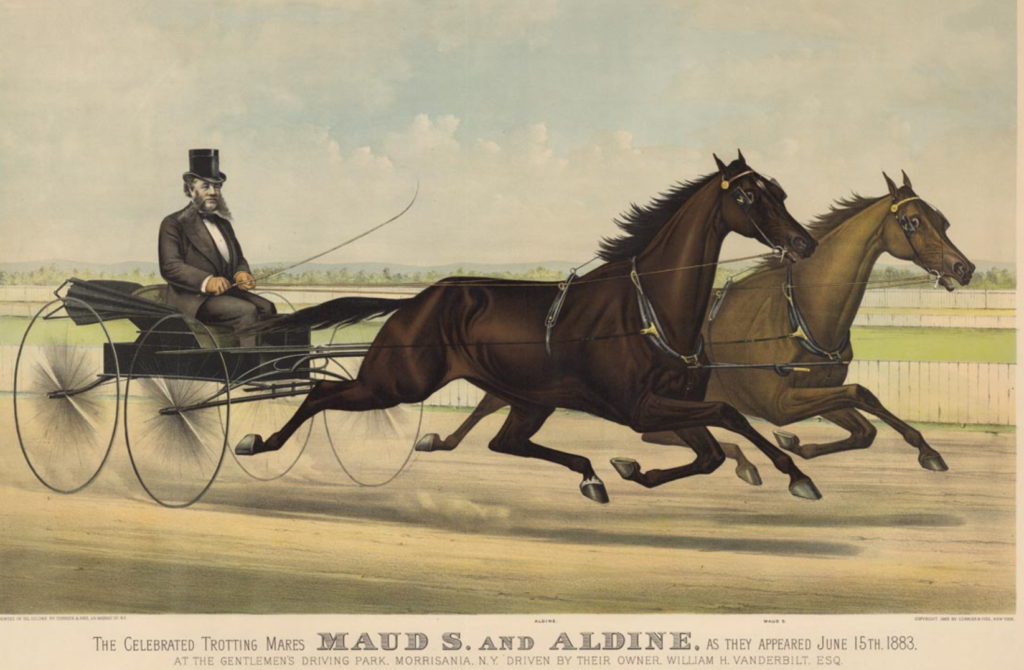

This era was the heyday of road racing in Harlem and the Bronx, when high-society men like William K. Vanderbilt, Jay Gould, William Rockefeller, William C. Whitney, Leonard Jerome, and Robert Bonner would put on a spectacular show by racing their trotters on snowy days and on every spring and summer afternoon.

Thousands of spectators would gather on the grassy banks of the streets to watch and cheer on their favorite trotters as they headed down Seventh Avenue in Harlem and Jerome Avenue in the Bronx.

No doubt the men had great fun racing down the street, but their real goal was Fleetwood Park racetrack, where gentlemen could trot their horses against time on a one-mile oval track.

One of the favorite features of these daily equine displays were the social gatherings and suppers at the various roadhouses scattered along Jerome Avenue, on the east side of Macombs Dam Bridge.

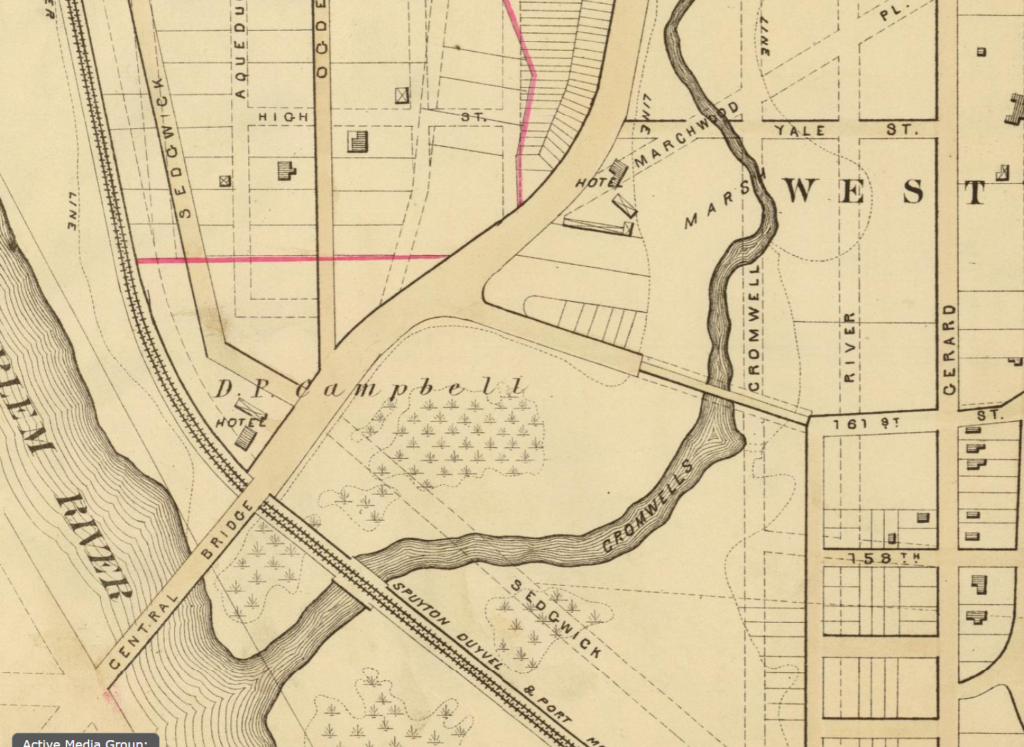

Johnny D. Barry’s, aka The Romantic House, was the first roadhouse as one crossed over the old wooden bridge (see illustration below). Next there was Gabe Case’s place along Cromwell’s Creek, where one could get the finest fish supper. Beyond Gabe’s, about a mile farther up Jerome Avenue, was Judge Smith’s roadhouse at East 167th Street, which was just a few blocks west of Fleetwood Park.

One of the most famous customers of these popular roadhouses was William K. Vanderbilt, who ruled the horse-racing world with his trotters Aldine, Early Rose, Maud S, Lysander, and Leander. Vanderbilt, whose father (Cornelius Vanderbilt) was also a frequent customer, never missed a stopover at the three main roadhouses on a winter sleigh ride or while on his way to Fleetwood Park. At Gabe Case’s, he would rest for a while on the piazza or join his fellow horsemen in the conservatory, aka lookout tower.

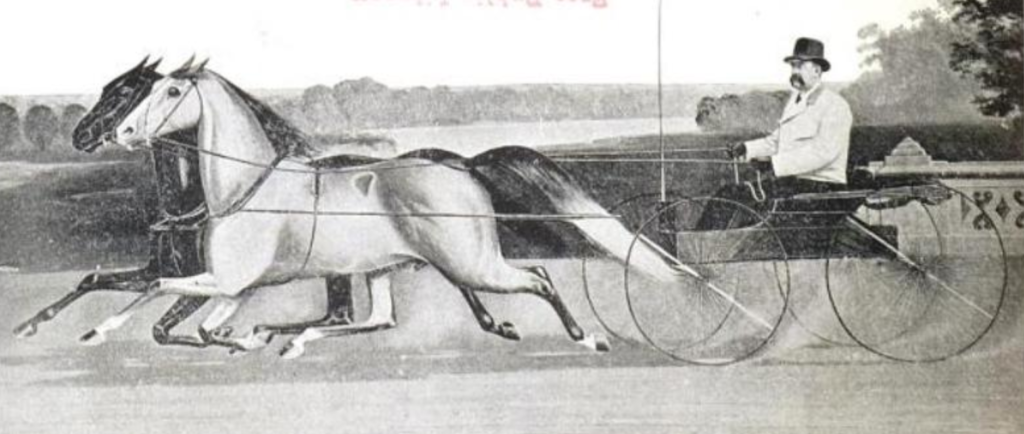

Although Vanderbilt was the king of the racetrack, when it came to sleigh riding, no one could beat stableman and Harlem River Speedway superintendent John J. Quinn. Every year for almost 25 years in a row, Quinn won the coveted magnum of wine at Gabe Case’s roadhouse with his many trotters, including Wildwood, Lutegard, and Dexter K.

Quinn owned the Eureka boarding stables in Harlem on 124th Street just off Seventh Avenue. As the stableman once told the press, “three snowflakes meant sleighing.” He had a standing order with the stable foreman to have the fastest horse in the stable ready at the stable door at the first sign of snowfall.

Sometimes Quinn would cheat by jumping the gun too fast and dragging his sled’s runners on the bare macadam. Gabe Case would have to send him home without the magnum; a new race would take place the day after the first snowfall was adequate for proper sleigh riding along Jerome Avenue.

A Brief History of Gabe Case and His Jerome Avenue Roadhouse

Although all of the roadhouse owners reportedly awarded a magnum of wine or champagne to the fastest sleigh riders, Gabe Case’s place had a great reputation for several reasons.

Gabe Case was born on Clinton Street in the Lower East Side of Manhattan in 1830. He was married for a short time, but his wife reportedly died at a young age, sometime prior to 1880. The couple never had children.

Gabe’s first business venture was a hotel called The Fulton, which was at 18th Street and Fourth Avenue. When the Fleetwood Park racetrack opened in 1871, he took a job managing the clubhouse there. Like the other men who raced at Fleetwood, Gabe was also a horseman who enjoyed racing his chestnut trotters Tom and Jerry at the track or taking longer rides with his reliable distance horse, Decoration.

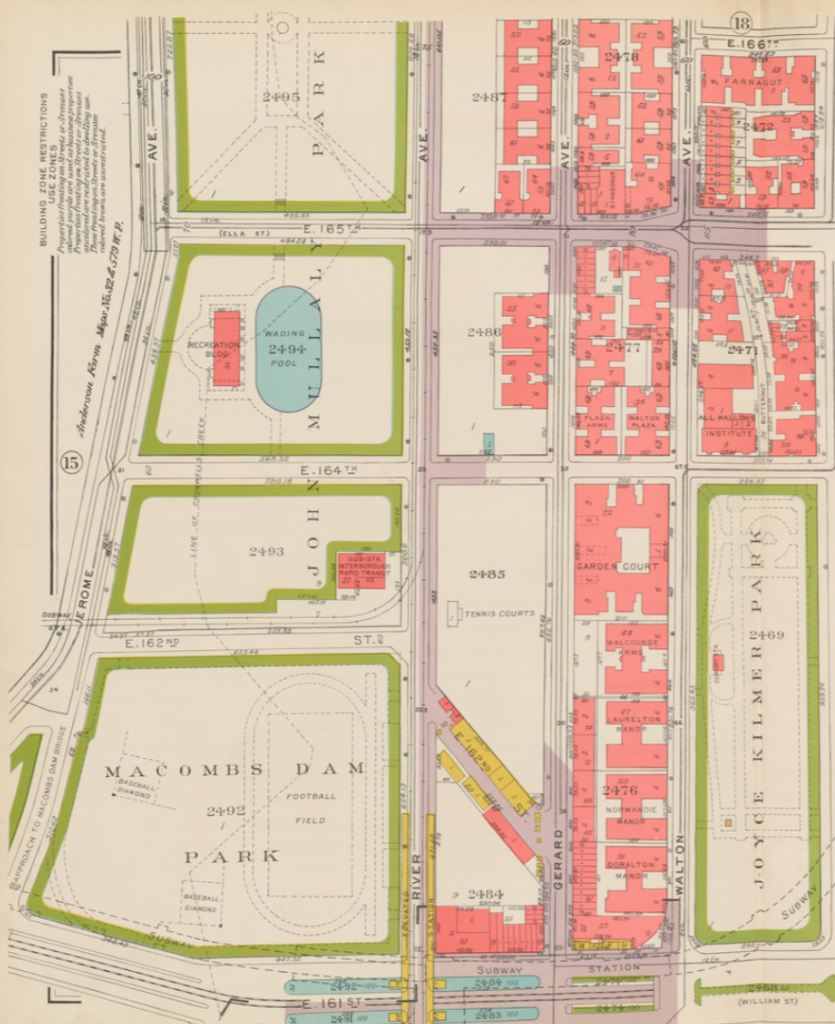

Sometime prior to 1875, a hotelier named William H. Florence built a roadhouse on Jerome Avenue, just north of present-day 162nd Street. The roadhouse property backed onto Cromwell’s Creek, named for the descendants of John Cromwell, a nephew of Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell. In the late 1700s, James Cromwell used the waters of the creek to propel his mill.

William Florence had owned a large hotel on 154th Street and Eighth Avenue, just west of Macomb’s Dam bridge in Manhattan. He lost the property in 1873 after allowing ex-Assemblyman Tomas C. Fields to use the hotel as collateral in lieu of a $5000 bond. Fields skipped town, and Florence’s hotel was seized.

Florence’s new building had a commanding view of Jerome Avenue and the bridge, and was surrounded by a beautiful forest along Cromwell’s Creek, which was a popular place for swimming, fishing for striped bass, and ice skating.

Gabe Case took over the lease from William Florence and named it Gabe Case’s Hotel.

In addition to the renowned sleigh-riding contests, Gabe Case hosted many events at his roadhouse, including a popular quail-eating contest and a hog-guessing contest (guess how many pounds it weighs). Gabe Case’s was also headquarters for the Hoboken Turtle Club, whose members would host annual clambakes and turtle soup dinners at the hotel. News reporters liked to point out that Gabe’s large size (at one point he reportedly weighed 285 pounds) was probably a good advertisement for his food business.

In addition to his horses, which lived in stables attached to the roadhouse, Gabe Case kept a green parrot, several canaries, and a few bull terriers at the roadhouse. During the winter months, Gabe reportedly loved to sit in the hall close to his beloved talking parrot as he greeted all the sleigh riders.

The Final Days of Gabe Case and His Roadhouse

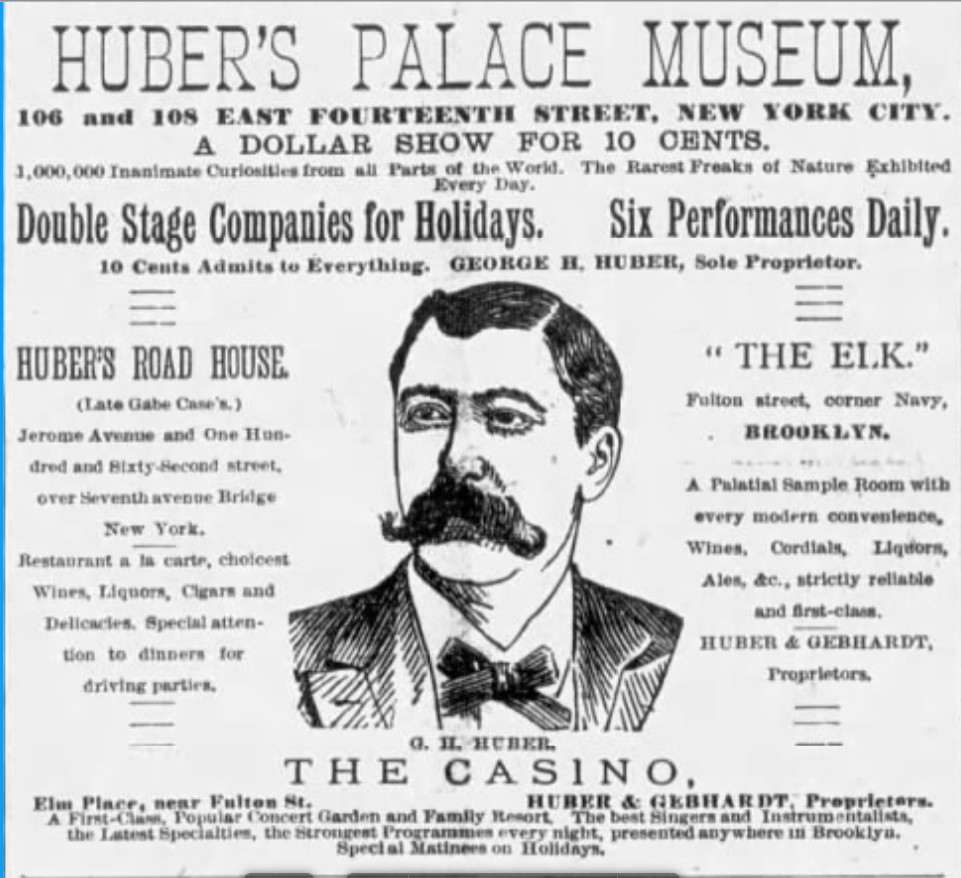

In 1886, a museum man named George H. Huber purchased Gabe Case’s place for $25,000. The deal allowed Gabe to continue running the roadhoase–where he also lived with his nephew, Charlie Russell–until his lease expired in 1890.

On March 30, 1890, just two days before Gabe was scheduled to take over the lease at the old Mount Saint Vincent House in Central Park (which later became McGown’s Pass Tavern under Case’s proprietorship), his horse Decoration died of complications from colic. The horse, whom Gabe had purchased from Robert Bonner for $215 in 1879, was buried near the old Fleetwood Park; a monument was erected there in his honor.

Gabe postponed his move to Mount Saint Vincent, possibly due in part to his horse’s passing.

Much has been written about Gabe Case’s years at McGown’s Pass Tavern, so I’m skipping that part for another story at a later time. So we’ll fast-forward to July 1901, when Huber expanded Gabe’s old Jerome Avenue roadhouse to accommodate vaudeville performances.

By this time, the interest in racing trotters along Jerome Avenue was waning, especially since Fleetwood Park had shut down a few years earlier. Gabe was still awarding the magnum of wine to sleigh riders, but now the horsemen were racing only as far as McGown’s Pass Tavern in Central Park.

On June 1, 1904, Gabe Case died in his residence at the tavern at the age of 74. A large funeral procession led from his tavern to Calvary Methodist Episcopal Church at Seventh Avenue and 129th Street–this was the first ever funeral procession through Central Park. Case was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery.

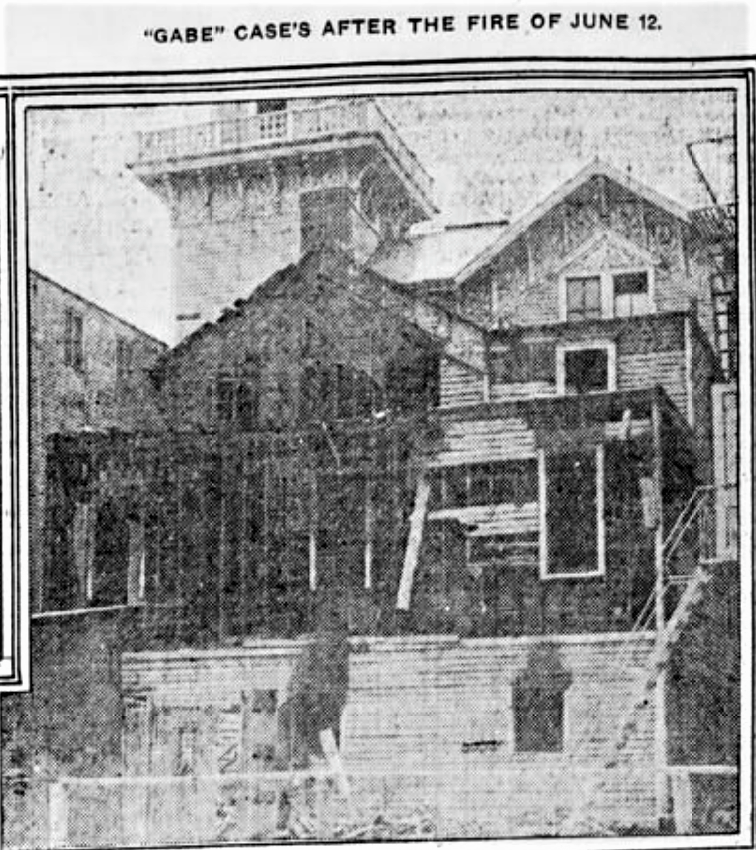

Eight years after Gabe Case’s death, on June 12, 1912, a fire caused considerable damage to a wing that had been added to his old roadhouse on Jerome Avenue. This building was occupied by a fight club where boxers could train and compete. The main building, including the lookout tower, was not damaged in the fire.

Three years later, Huber decided to sell all of his vast holdings on Jerome Avenue, which included 56 lots between 162nd and 170th Streets. Apparently the old roadhouse had been repaired by this time; New York State Senator George Thompson reportedly purchased it for his wife as a Christmas gift.

I’m not sure what Mrs. Thompson did with her gift, but I do know that by 1924, the old Jerome Avenue roadhouse was on its way out.

In 1924, the City of New York acquired land for a park on seven blocks to the east and west of Cromwell Avenue.

Then in 1929, the Bronx County Park Association extended Macombs Dam Park above 162nd Street along Jerome Avenue, atop the old Cromwell’s Creek. They named the park in honor of John Mullaly, a news editor and secretary of the Parks Commission.

Mullaly was a strong advocate of setting aside parkland in the Bronx. His efforts culminated in the 1884 New Parks Act and the city’s 1888-90 purchase of lands for Van Cortlandt, Claremont, Crotona, Bronx, St. Mary’s, and Pelham Bay Parks, as well as the Mosholu, Pelham, and Crotona Parkways.

John Mullaly park opened on August 24, 1932.

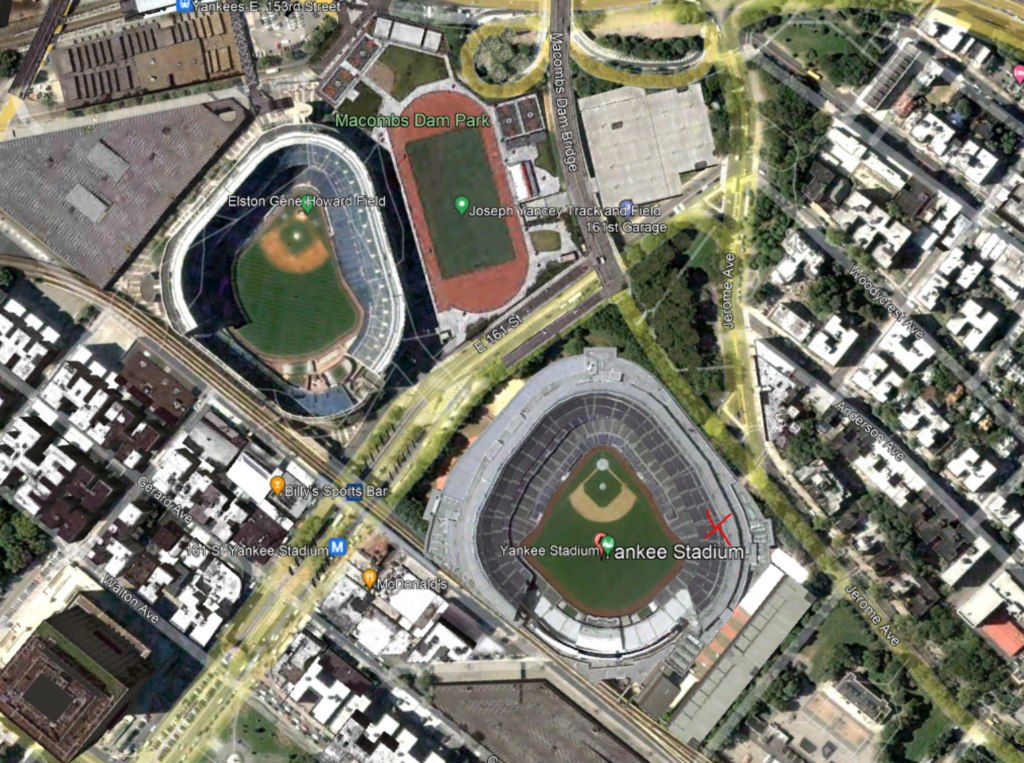

Groundbreaking for the new Yankee Stadium–which replaced the old 1923 stadium just south of East 161st Street–began in August 2006. The first ground was broken on a running track at Macombs Dam Park and at the southern end of John Mullaly Park.

Today, if you’re sitting way out in left field at the stadium, you can think about Gabe Case’s roadhouse and the famous horsemen who raced their trotters to that very location on summer afternoons or whenever it snowed in Old New York.

All that equine history took place right under your seat.

Wow, that’s a lot of history packed into that article, Peggy! I really enjoyed it. I have an article from the NY Times in 1926 about the area around the Fleetwood track having a neighborhood where horseshoeing forges lined the street, but were closing as the horses disappeared from the streets. One farrier interviewed lamented that his shoeing supplies were delivered to him in a truck instead of by wagon. I’m really looking forward to the new HBO series, “Gilded Age” to see how it represents pets and horses of New York City. I hope they used you as a consultant for authentic history! Keep up the great work, Peggy, and happy new year!

Fran, I’m so glad you enjoyed this story. I put a lot of time and heart into these tales, so it’s always much appreciated when people enjoy them. I don’t get HBO, so I won’t be able to tune into Gilded Age. But it sounds like it could be interesting. I really loved The Alienist on TNT, which was not shot in NYC, but which did incorporate many horse scenes and even an intense scene with a cat. I would have loved to have been a consultant for the animal scenes!