Once upon a time, a renowned employee for the Southern Railway lost a battle to a cat that had broken into his home on West 44th Street. Before I tell you about this battle, allow me to introduce you to Alexander Stephens Thweatt, a Southern gentleman who dedicated his life to the railway.

Alexander Thweatt was born in Milledgeville, Georgia, in 1862. He was the son of Peterson Thweatt, Confederate Comptroller General for Georgia during the Civil War.

Alex started working at the age of 12 as a clerk in the ticket office of the Richmond and Danville Railroad in Atlanta. By the age of 20, he was a district passenger agent for this railway.

In 1885, Alex married Nannie Neill Hays of Louisville. Nannie’s father was Major Thomas H. Hays, another Confederate veteran and a former State Senator of Kentucky. Her grandfather was John L. Helm, governor of Kentucky in 1850 and 1867.

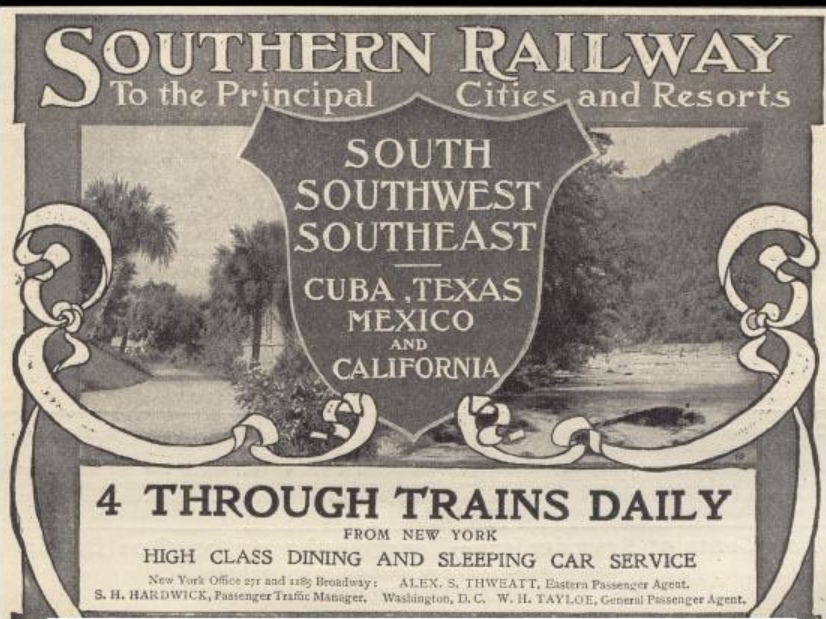

The couple moved to New York City around 1894, when Alex was promoted to Eastern passenger agent for the newly reorganized Southern Railway. At this time, the railway, which offered passenger service to the Carolinas, Georgia, Florida, Mexico, and California, had offices in the National Shoe and Leather Bank Building at 271 Broadway.

Alexander actively marketed the Southern Railway, placing national ads promoting events such as Mardi Gras and Atlanta conventions, which would attract numerous rail passengers from New York, Baltimore, and other eastern cities on the rail line. He also promoted himself by sharing work stories or little snippets of conversations that he overheard during his day, like this snipped below.

The Great Possum Escape at the Southern Railway Office

By December 1904, when this next story took place, the Southern Railway had a second New York City office at 1185 Broadway, on the northwest corner of West 28th Street, in a building attached to the Fifth Avenue Theatre.

According to the New York World, Alexander “gave an impromptu exhibition of how to handle a possum” on New Year’s Eve that year. “His appearance in the role of an animal trainer was in the railway office at 28th Street and Broadway, in the presence of an awe-stricken crowd of clerks, policemen, citizens, and Sam, the porter.”

Apparently, Alexander had received a Christmas present of four large persimmon-fed possums from friends in North Carolina. The possums reached his office late, were fed, and left in their crate for the night. When Alexander came downtown the next day, he found the sidewalk in front of his office blocked by young boys with their noses glued to the big plate glass windows.

“What’s the trouble, Sam?” he asked the porter, who was running excitedly from one door to another.

“Good Lawdy, don’t you see. Eem blamed possums has done got loose and I can’t ketch ‘em.”

Alexander laughed at Sam. “What, you can’t catch a possum?” Sam explained that he was born and raised in New York and had never ever seen a possum before let alone tried to catch one.

Seeing that something had to be done as the crowd grew larger, Alexander threw off his overcoat and went inside. He gently kicked the first possum, which then played dead. Then he reached down and put his forefinger under its tail.

The possum curled its tail curled around his finger, allowing Alex to lift it back into the crate. He did the same with the other three possums.

“You see, I was raised in the South,” he told the crowd. “I’ve been possum hunting many times. When a boy I learned that all you had to do was to touch a possum’s tail. The possum will play ‘dead’ immediately and you can do anything you want to with him.”

Alex said he would send three of the possums to Southern friends living in New York City. The other he reportedly had killed and later served with candied yams—yuck (possum was a very popular Southern dish at this time).

Now, Alexander may have been a good possum wrangler, but when it came to other animals, he was apparently a bit challenged.

The Cat Burglar of West 44th Street

One night in March 1900, after retiring to the bedroom in his ground-floor apartment at 257 West 44th Street, he was awakened by his wife Nannie. She whispered to him, “There must be burglars in the house. I’ve heard them.”

Alex got his revolver and crept out of bed. He was groping around in the darkness when he heard a loud yell. Somehow, he managed to jump and land on top of his dining room table (I’d be very impressed if he did indeed pull off this cat-like maneuver, especially since the press once called him “a somewhat corpulent gentleman”).

He turned on a light and searched the room, but there was no burglar in sight. However, the front window was partly open.

While continuing to search the room, Alex spied a large black cat trying to get out the window. He dropped his revolver, picked up a broom, and chased the midnight cat burglar.

During the battle, the poor man sprained his right ankle, broke two window panes, smashed all the crockery on a sideboard, and upset a parlor lamp. Luckily, the lamp—if powered by kerosene–was not lit at the time.

The cat escaped without harm. Maybe, just perhaps, this cat was an ancestor of Abe Lincoln, the brave kitten who took up residence at the Hotel Lincoln, the large hotel that was constructed in 1927 on the site where Alexander and his family lived in 1900.

The Final Days of Alexander S. Thweatt and the Southern Railway

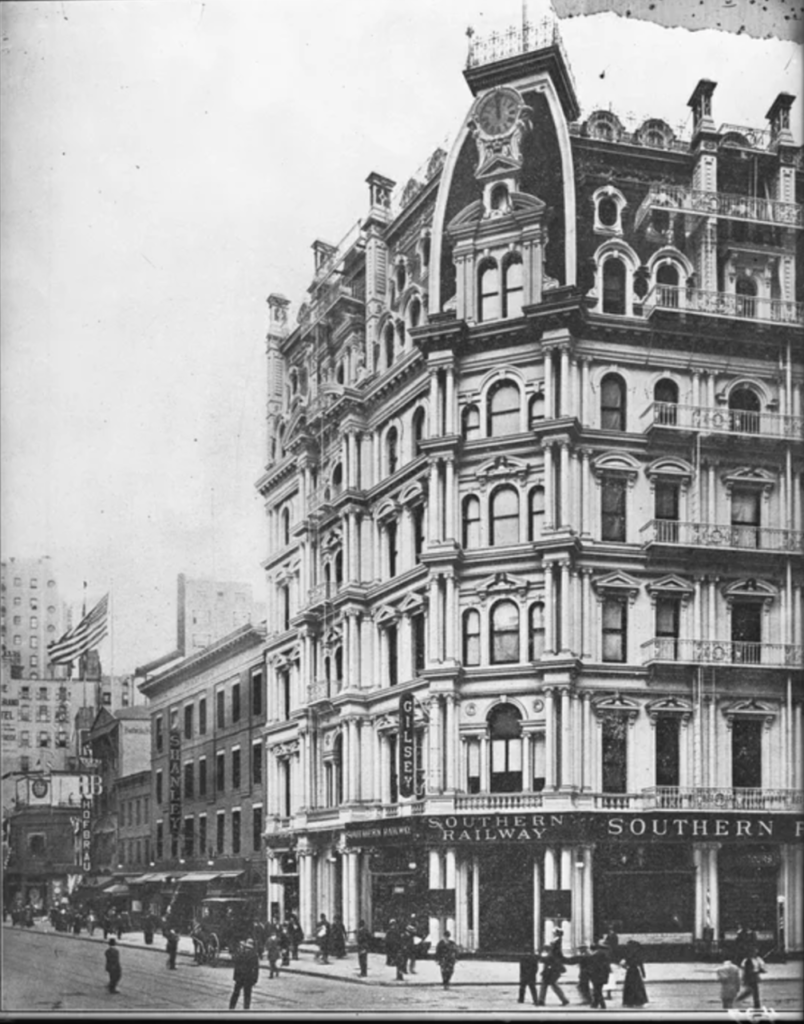

During the 1900s, the Southern Railway moved its New York City offices several times. In 1906, they moved to the ground floor of the Gilsey House at 1200 Broadway, on the northeast corner of East 29th. (Maybe the owners of the Fifth Avenue Theatre didn’t want to take any more chances with escaped possums?)

By 1914, the offices of the Southern Railway had taken over the retail space once occupied by upscale jewelry store Howard & Co. at 264 Fifth Avenue, a former mansion that had been the home of New York City merchant A.T. Stewart.

Alexander died in his home at 600 West 150th Street following a brief illness on December 4, 1917. He was survived by his wife, four married daughters, a son, and four grandchildren. He was buried in Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York.

Following Alexander’s death, there were no more newspaper ads promoting the railway offices at 264 Fifth Avenue. Perhaps Southern Railway moved its offices in 1917, but the ads stopped, never to run again, when the old ticket agent died.

From the mid-1920s to 1930, the offices for Southern Railway were located at 152 West 42nd Street. A man by the whimsical name of R.H. De Butts was the Eastern passenger agent.

In 1971, Amtrak took over most intercity rail service. Southern Railway initially opted out of turning over its passenger routes to the new organization; however, it shared with Amtrak operation of its flagship train, the New Orleans-New York Southern Crescent. Under a longstanding haulage agreement, Amtrak carried the flagship train to all stops north of Washington.

By the late 1970s, growing revenue losses and expenses forced Southern to exit the passenger rail business. It handed full control of its passenger routes to Amtrak in 1979.

Today, the Crescent runs a daily train from New York City to New Orleans. I’m a big fan of trains, so this trip is on my bucket list. I’ll raise a toast for Alexander while we’re rolling through Georgia.