“Somewhere in New York there is wandering in a dark alley or a secluded street, perhaps in a starving condition, an heiress to part of a small fortune.”—Baltimore Sun, August 3, 1925

Mrs. Elizabeth W. Berhm, a kindly widow of about 61 years old, had always devoted herself to animals. She was known in her Carnegie Hill neighborhood as the “cat woman” because her home was always open to stray cats. In her small, two-room apartment at the rear of 172 East 85th Street, milk and kindness were always waiting for any cat that needed it.

No doubt, then, the neighbors must have been shocked to learn that Elizabeth had almost taken the life of her own pet cat, Dunder, while she committed suicide.

Born in Germany in 1864, Elizabeth Berhm came to America in 1880. She and her husband, Eugene, married late in life, following the death of Eugene’s first wife, Pauline, in 1914.

Ten years Elizabeth’s senior, Eugene owned a cigar store and had one grown son, also named Eugene. According to census reports, Elizabeth and Eugene had been living in the Carnegie Hill apartment on East 85th Street since at least 1920.

Sometime during the spring of 1925, Eugene was killed by an automobile (I don’t know if he was in the car or if the car struck him while he was walking). Alone in the world, Elizabeth focused all her time and affection to stray animals.

Although she already had Dunder, a house cat who was about seven years old, the number of Carnegie Hill stray cats that visited her home increased every week. Even the stray dogs considered her a friend.

But despite all the attention she got from her animal friends, the grieving widow could no longer go on without her husband.

On Saturday night, August 1, 1925, George Hess, the janitor for the five-story tenement building, smelled gas. After tracing it to Elizabeth’s apartment, he summoned Policeman Christian Kiel of the East 67th Street Station. Officer Kiel smashed a window and found Elizabeth lying on the floor next to her bed.

Apparently, she had struggled while the gas came to her through a tube attached to a chandelier. When she fell off the bed, she tore the lighting fixture from the ceiling. The gas quickly filled the room.

After instructing Hess to call for medical help, Officer Kiel found Dunder squirming in a corner, trying to fight off the effects of the gas. The policeman tossed the cat out the window so she could get some fresh air.

Physicians attempted to revive Elizabeth with a Pulmotor, but they eventually had to give up and pronounce her dead. As Officer Kiel was jotting down the outcome in his notebook, Dunder came back into the room. Completely revived by the fresh air, he meowed loudly as he watched over his dead mistress.

While searching through the apartment, police found a photograph of Eugene. On the back of the photo was printed, “Please bury this with me.”

Upon further investigation, they found a will and a note stating she could no longer live without her husband. In her will, she had directed that part of her $4,000 estate go towards providing a comfortable home for Dunder for the rest of the cat’s life. The rest was to be divided among the city’s homes for cats and dogs.

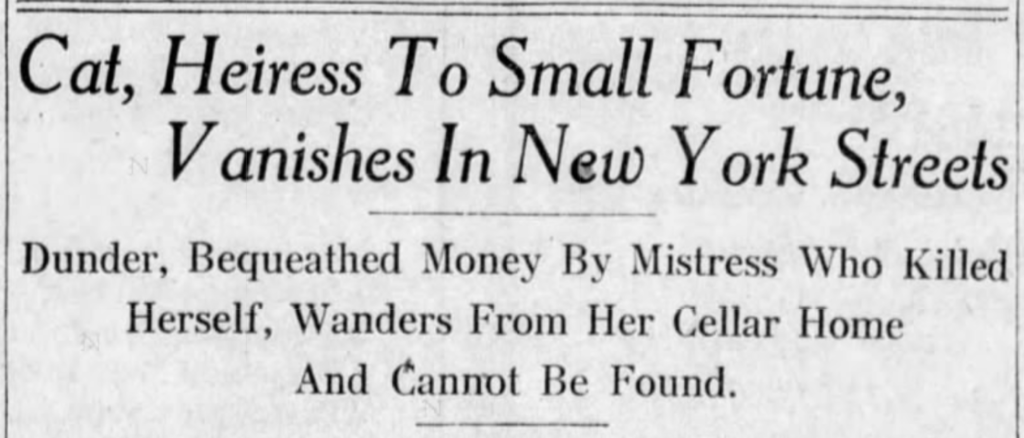

Hess agreed to take care of the cat temporarily, so he brought the cat to the cellar (you’d think he would have taken the $4,000 and promised to care for the cat forever). When he went to look for her the next morning, she was gone. Hess searched the apartment building from cellar to roof, with no success.

She evidently had wandered away, still dazed and confused by her experience, and obviously not loving her new living conditions. As the Daily News wrote, “Today the former pampered apartment pet is trying to scrape a precarious living out of the alleys and gutters of New York, in competition with cats who have been doing it all their lives.”

A story about Dunder in the Muncie Evening Press said, “She knew little of the ways of alley cats in New York. She had no education in the finesses of snitching fish from fish markets or getting into secluded back yards and helping herself to spilt milk and bits of food. Like all other cultured cats thrown suddenly upon their own resources, she may starve to death, while a fortune, as reckoned when the standards and needs of cats are considered, await her.”

When asked how the cat would be found, Hess said he didn’t have a clue as there was no one alive who could positively identify the cat. At first it was reported that Dunder was an Angora, but Hess disputed that. He said she was just a plain, large black cat, “respectable without having been necessarily aristocratic.”

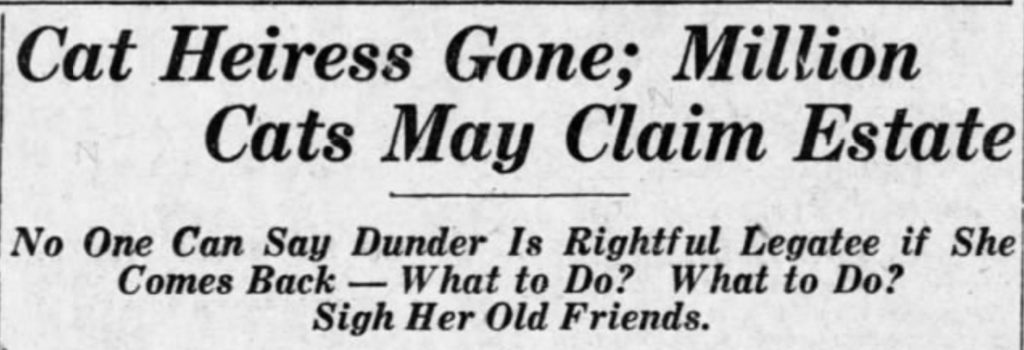

As one New Jersey newspaper observed, “Any one of a million alley cats can claim part of a $4,000 bequest because there is no human being who can positively identify Dunder, the rightly legatee.”

Several fictional cats responded to the story, including Thermy, the weather cat for the Evansville Press in Indiana. Thermy theorized that poor Dunder had drowned and gave thought to traveling to New York to claim he was Dunder and collect the money. The cat “wrote” the following:

“With milk selling at seven cents a pint, I could have cream for the rest of my life! And believe me, if I get that $4000, no more forecasting for me. The only predictions I’ll make then will be for three round bowls of rich cream per diem. The forecast? Oh, guess at it!”

If you enjoyed this story, you may want to read about the cats and dogs that saved 37 lives during a gas leak on the Upper East Side in 1889.

172 East 85th Street and Carnegie Hill

Incidentally, Elizabeth’s suicide was not the first horrific event that had taken place in the tenement building at 172 East 85th Street.

In 1890, Henry Colwell stabbed his wife, Louisa, seven times in the hallway of the building during a drunken assault. Henry was arrested but he tried committing suicide by cutting the veins of his legs. Louisa was taken to the hospital, but she was not expected to live.

And in 1895, John Hill, a 32-year-old man living in the building, attempted to kill himself by cutting his throat. He was severely wounded and taken to Harlem Hospital. A year later, John Haggerty suddenly died in the apartment of unknown causes.

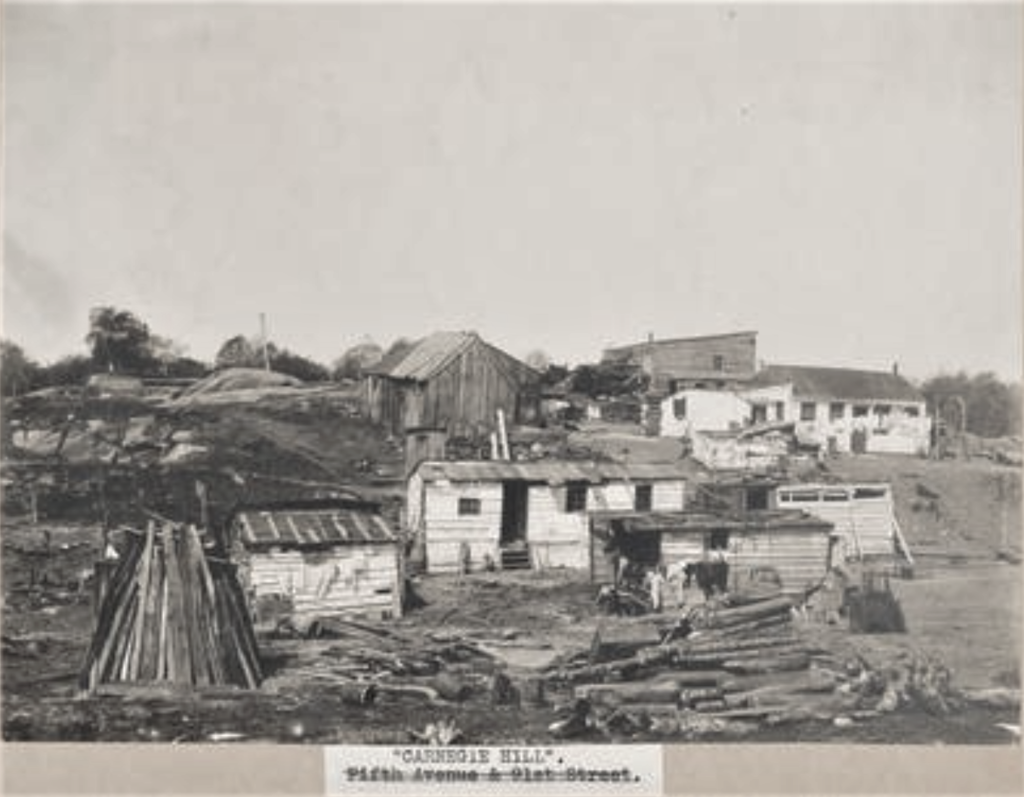

Whether the late 19th-century tenement building on East 85th Street was jinxed or not, we do know that it was constructed on the southern-most edge of what would become known as Carnegie Hill, named for the mansion that Andrew Carnegie built on Fifth Avenue and 91st Street in 1902.

The earliest known history of this part of Manhattan goes back to a seasonal village for the Algonquian Nation Konaande Kongh, which was located on a hillside stretching between present-day 93rd and 98th Streets along Park Avenue. The village was surrounded by dense woods of maple trees and berry bushes to the west and a cultivated fertile plain to the east for growing vegetables and herbs.

In October 1667, Governor Richard Nicolls granted large tracts of land in New Haerlem (which encompassed from about 74th Street to 129th Street) to Thomas Delavall, John Verveelen, Daniel Tourneur, Joost Oblinus, and Resolveert Willliam Waldron. The patent included all houses, buildings, barns, stables, orchards, gardens, mills, ponds, fencing, and other natural and man-made structures on the land.

Waldron’s allotment was known as Hellgate or Horne’s Hook, and primarily encompassed the land from 75th to 94th Streets between Third Avenue and the East River. The family home, Waldron Hall, was located north of 86th street and east of Avenue A. Built in 1685, It was demolished in 1870 following a fire.

Following Resolveert’s death in 1690, the Waldron Farm passed through several generations of Waldrons, including Samuel, Johannes, William, and Adolph. At one point, the farm comprised 156 acres, which included the original patent plus additional lands acquired throughout the years.

Just prior to the Revolutionary War, Abraham Durye, a New York merchant, purchased the farm at auction. Although Durye’s heirs retained a small tract near 93rd Street, most of the irregular, triangular tracts were conveyed through the early 1800s to John G. Bogert, Nathaniel Sandford, Xaviero Gautro, Natianiel Prime, Edward Douglas, and William Rhinelander.

Land speculation in the Carnegie Hill area did not go into full swing until the late 1870s, with the opening of the IRT Third Avenue Elevated Railroad in 1878.

never got the pay i deserved. weather looks pretty good today, though.

65 and sunny here in indiana. rip dunder rip justice