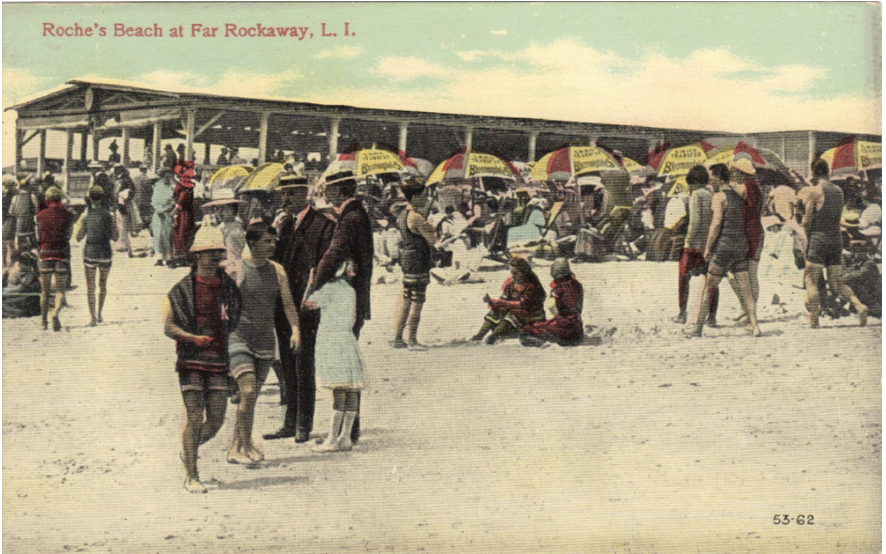

When Martin Ward, the attendant at Roche’s Beach Pavilion in Far Rockaway, Queens, found a tiny monkey in the bathing house, he brought him to the proprietor of the private beach resort. Edward Roche didn’t know what to do with the monkey, so he called the nearby police station for some help.

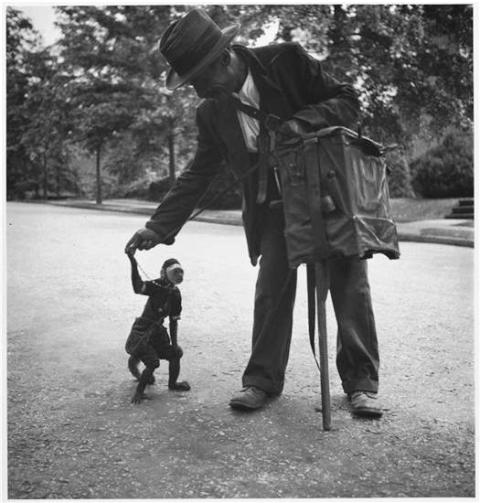

Patrolman Norman King, the largest police officer of what was then the 279th Precinct, responded to the beach resort. When he got to Roche’s, he found about three hundred children surrounding a little monkey of the “organ-grinder type” wearing a life-saving belt and a red bathing suit adorned with rosettes.

Apparently, some Yale undergraduates had spent the day at the Far Rockaway beach resort the previous afternoon, so King believed that a few sophomoric young men may have had something to do with the bathing beauty.

King placed the tiny monkey in his pocket and walked back to the police station, which occupied an old frame building on the south side of Broadway (present-day Cornaga Avenue) opposite Mott Avenue. As he walked up Beach Nineteenth Street toward Broadway, the children followed behind, no doubt delighted by the monkey peeking out from the policeman’s pocket and making faces at them.

Lieutenant Scoville didn’t know how to enter the monkey in the blotter, so he noted the animal as “lost, strayed, or stolen.” Then he tied the little primate to a post on the back porch.

The men told a New York Times reporter that they never had a prisoner that required so much work. It was determined that at least five policemen had to stand guard over the monkey in order to keep him in line.

The fate of the monkey in the red bathing suit was not reported, but for one day, at least, the men of the Far Rockaway police station could claim they had a monkey prisoner.

A Brief History of Roche’s Bathing Pavilion at Far Rockaway

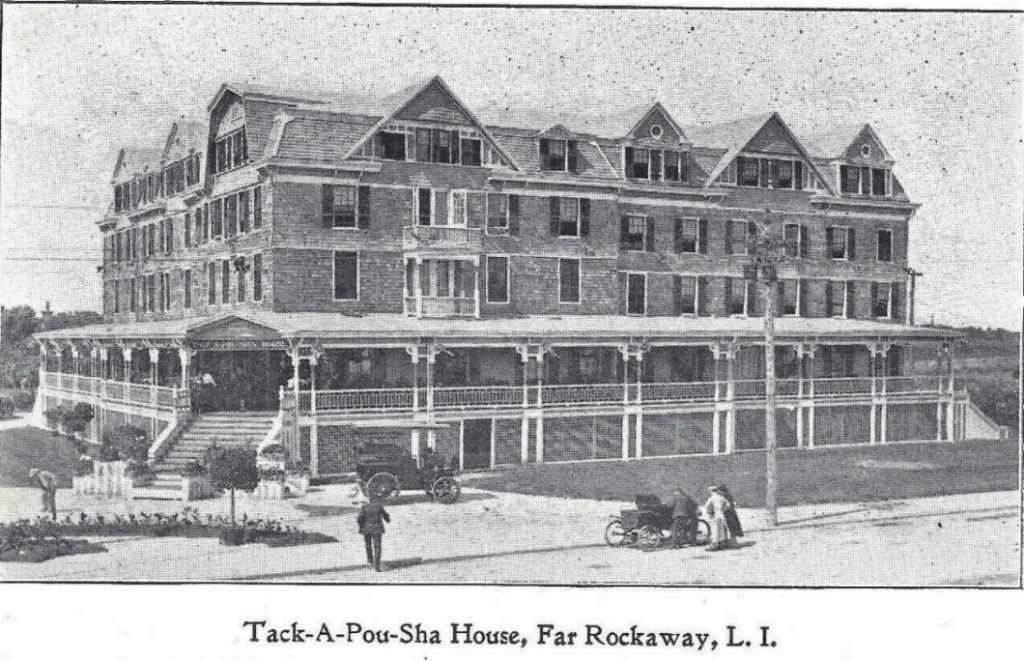

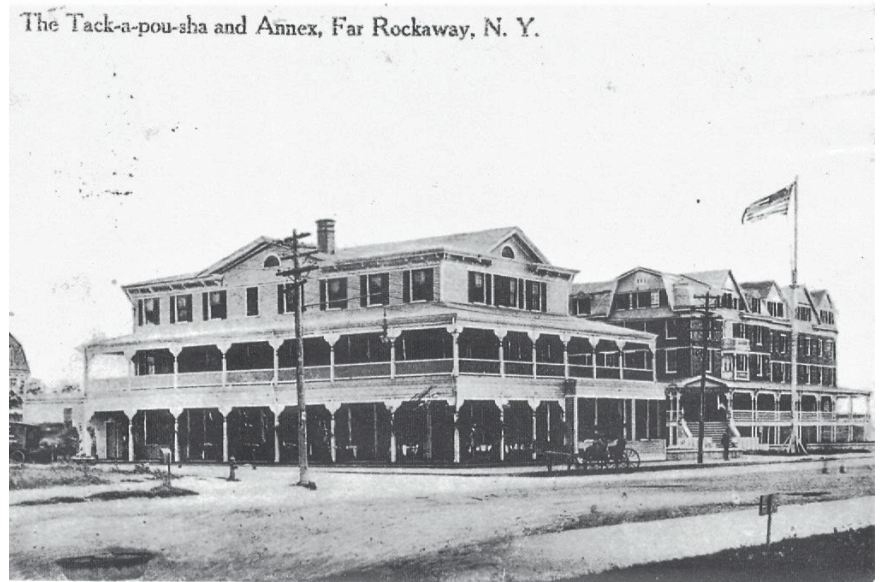

Edward Roche was the son of David Roche, a Far Rockaway pioneer with vast real estate holdings along South Street (Seagirt Boulevard). One of Roche’s largest holdings was the Tack-a-Pou-Sha House at Heyson Road, which had been constructed around 1890. The large hotel replaced the family’s smaller hotel on the same site and was named for Tackapousha, a Lenape native who was the first person to sell land in the Rockaway Peninsula to a European.

The large, four-story hotel could accommodate 300 guests, and offered stables for horses and carriages (and later a garage for motorized vehicles). The hotel was so successful that Roche constructed an annex, which he called the Dolphin Roadhouse and Hotel. Altogether, the two buildings featured a casino, restaurant, bowling alleys, billiard rooms, supper rooms, and a few single rooms for men.

In 1906, Edward purchased the property of the United States Hotel, which for years had stood next to the Tack-a-Pou-Sha House. The large hotel had been torn down during the winter months, and Roche planned on erecting 12 cottages upon the spacious grounds.

In addition to the cottages, Roche was at this time completing 1,000 new bathing houses along his 700 feet of beachfront property, which extended from Beach 17th to Beach 20th Streets. The bathing houses were divided into two sections: one for transient guests and the other for families who paid an annual membership fee ($7.50).

In 1912, Edward inherited his father’s holdings. He modernized the Tack-a-Pou-Sha and converted the Dolphin (which he had moved) to a rooming house. He also built four new hotels between Beach 17th and Beach 19th Streets as well as a large apartment complex.

Over the years, Roche’s Bathing Beach continued to grow in order to meet the demands of beachgoers and keep up with the competition. In addition to the bath houses (now 2,000), the resort offered chair and umbrella rentals, consignments and cigar booths, showers, manicuring services, hot saltwater baths, tennis courts, and handball courts.

For the kids, there was a park that featured slides, chutes, climbing towers, and seesaws. Adults had access to an athletic director, who assisted them with setting up games such as volleyball, ping pong, beach tennis, calisthenics, and baseball (all sports equipment was rented out for free).

In the early 1900s, a small steamboat called the Oysterette took bathers to the new sandbar that was forming where the outer beach, aka Hog Island, had existed before it disappeared during a great storm in the fall of 1893. Prior to that devastating storm, all the main bathing establishments of the Rockaways were located on the island, and two ferries transported people from the mainland (one boat operated along a cable and the other by sail).

When Edward Roche died of a heart attack at the age of 77 in December 1930, he left almost his entire estate, valued at $10 million, to a trust fund called the Edward and Ellen Roche Relief Foundation, the income from which was to be used to aid destitute women and children. Edward had never married, and his sister had died a year earlier, leaving only five cousins as the nearest living relatives. The cousins all contested the will, stating Roche was incompetent when he left his entire will to aid destitute women and children.

By November 1931, all of the cousins had withdrawn their claims and the will was admitted to Probate Court in Jamaica. Mrs. Margaret Rott, the nurse who had cared for Edward during his last 125 days of life, demanded she receive $125 to pay for the cost of two meals a day during that period (50 cents a meal).

Roche’s Beach continued operating through the 1950s. However, since 1937, title to the beachfront from Beach 9th to Beach 149th Street has been vested in the City of New York.

Edward Roche was buried at St. Mary’s Star of the Sea Cemetery in Lawrence, Nassau County. The last remnants of his beach and Ostend Beach were razed in 1963 to create O’Donohue Park, in honor of Mary O’Donohue, who purchased the land in 1868.