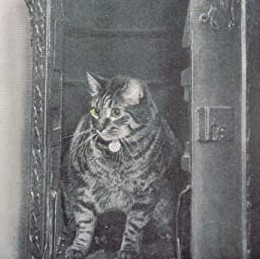

For fifteen years, Morris served as the ever-watchful feline mascot and mouser of the Sheepshead Bay police station, which was located in the Homecrest neighborhood of Sheepshead Bay. As official police cat of the 68th Precinct, it was his job to nab the rats and other vermin with which the rural district was infested.

Morris, described as a “husky gray-striped guardian of the law,” was donated to the Sheepshead Bay station in 1903 by members of the Sheepshead Bay Racing Association. The men christened him Morris in honor of his godfather, John Albert Morris, who conceived and built the Morris Park Racetrack in the Bronx in 1889.

If in fact Morris arrived at the Sheepshead Bay station in 1903, he would have spent his first three years in the old police station of what was then the 28th Precinct , which was located on Voorhies Avenue, just west of Sheepshead Bay Road (next to Mrs. Josephine Mason’s St. Elmo Village boarding house).

This station would have been problematic for Morris, because the basement of the old, two-story frame building would always flood at high tide. However, the old frame station also had a one-story barn, so that would have been a perfect place for Morris to do his mousing duties.

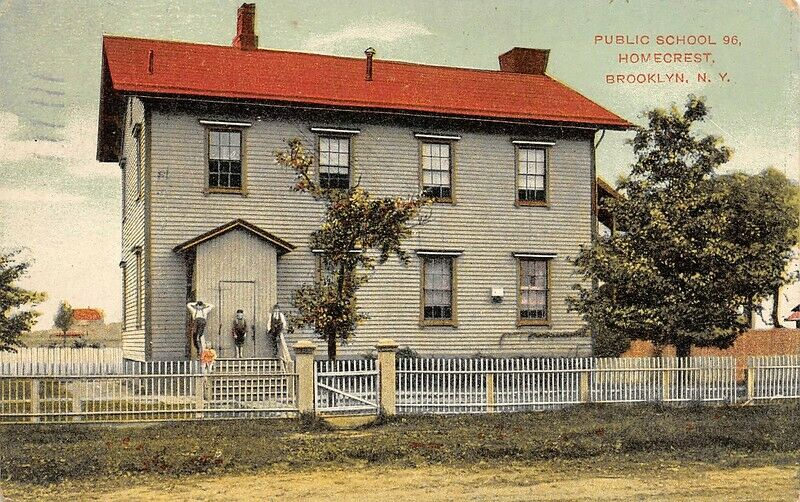

In July 1904, construction commenced on a new Sheepshead Bay station adjacent to the tracks of the Brighton Beach Railroad, on the northwest corner of Avenue U and East 15th Street. The large, Renaissance Revival-style station could accommodate 100 men, and featured electric lights and steam heat (a luxury for the suburbs). The station also had a two-story stable in the rear, where the Sheepshead Bay mounted squad kept their ten horses.

The new station was completed and furnished in May 1906.

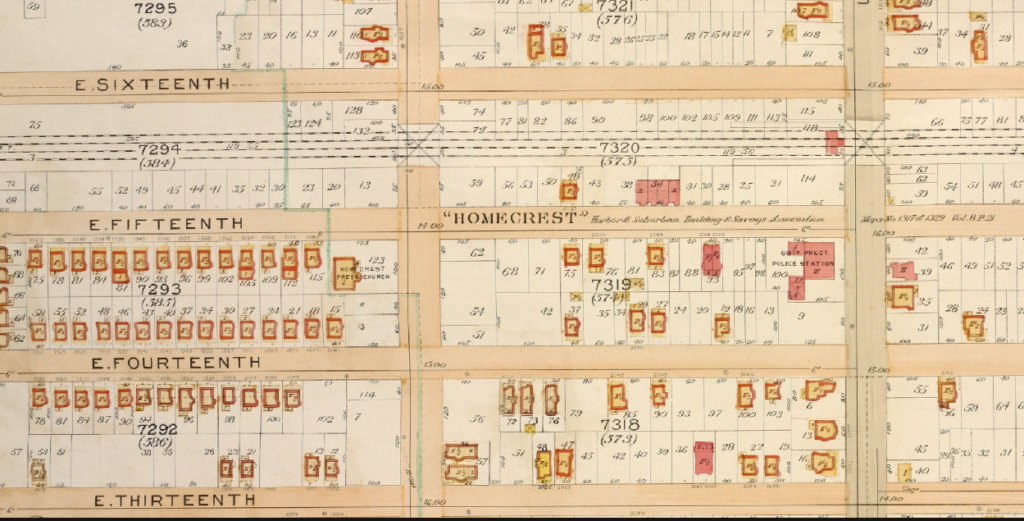

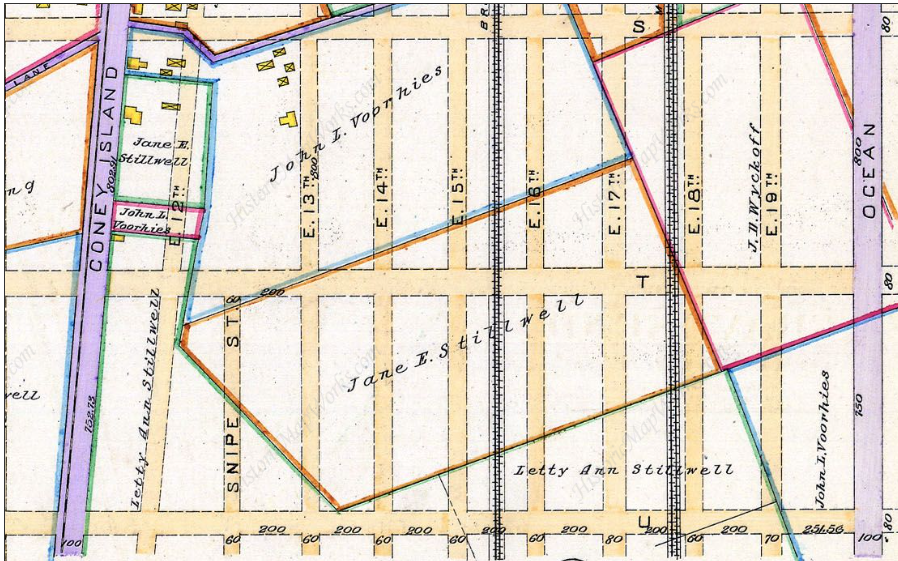

During this era, no doubt, there was plenty of work to keep Morris busy for fifteen years. As this 1907 map below shows, the police station was surrounded by many vacant lots, even while new homes of Homecrest continued to rise atop the old farmland. As the Brooklyn Standard Union noted in 1918, “Always on the job, he was never on trial before the Commissioner, charged with violations.”

On September 6, 1918, Morris was seated at his usual post, alongside Sergeant Ira Ferris at the desk, when he spotted a large rat trying to break into the precinct. With a “tremendous spring he landed on the intruder, but the exertion was too great, and the grim reaper claimed him for his own.”

Captain John Falconer, Sergeant Ferris, and the entire force of the precinct held “appropriate services.” Morris was buried in the front yard of the police station, his grab marked by a handsome marble slab, “suitable inscribed.”

The police station was demolished in 1979. Today the site of Morris the police cat’s grave is covered by a Duane Reade pharmacy.

A Brief History of the Superb of Homecrest

The Sheepshead Bay police station was located in a brand-new superb called Homecrest. Following is a brief history of this community.

In 1898, a new suburb of Gravesend proper began to rise from the grounds once occupied by potato patches and tomato vines. The development was three-quarters of a mile long a half mile wide, and was bounded by Coney Island and Ocean Avenues and Avenues V and S.

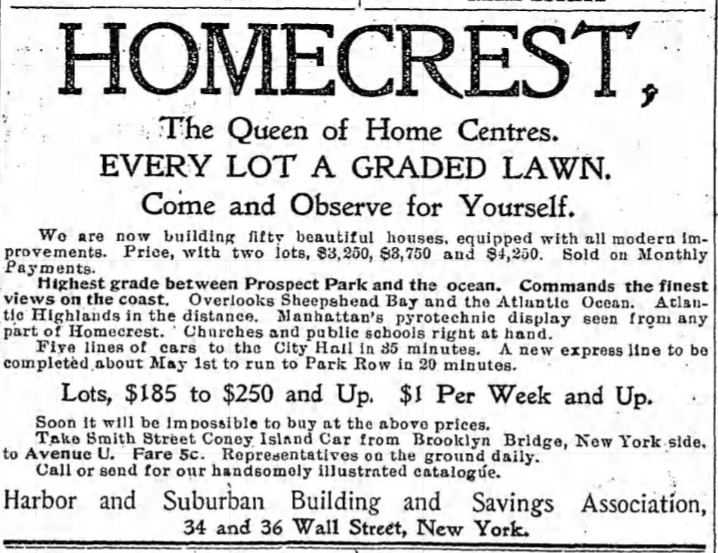

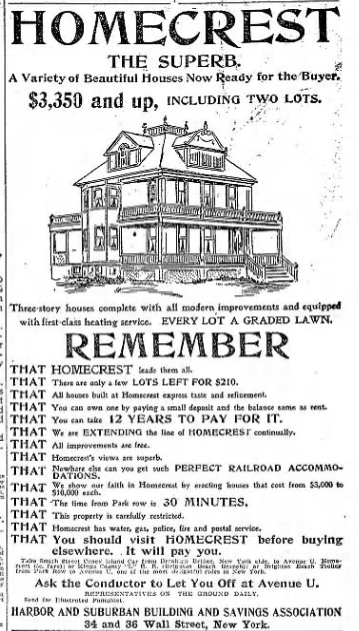

This tract formerly comprised the farms of Jane E. Stillwell, Letty Ann Stillwell, and John J. Voorhies—all descendants of the founding families of Gravesend. The first large parcel of land was purchased in November 1897 by the Harbor and Suburban Building and Savings Association, who had offices at 34-36 Wall Street. According to the 1890 map below, the police station was located on the former farm of Letty Ann Stillwell.

By 1899, about 50 houses—each costing $3,000 to $5,000—were occupied, and another 50 were nearing completion (the plans called for nearly 1,000 homes in total). Original residents included William Bennett, a Manhattan caterer; G.L. Smith, a Manhattan insurance broker; H.C. Hasselbrook, a Brooklyn Police Department official; and George A. Woods, a Brooklyn Fire Department official. Click here for a complete list of original residents, published in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

By 1903, eight miles of graded roads, concrete sidewalks, gas mains, and sewers were in place. The neighborhood also had electric lights in the streets and 2,000 silver maple trees to create “a shady retreat.” Advertisements like this one at left and below promoted the new community as a place to get a breath of fresh air after a hard day in the city.

In the beginning, developers had strict rules for the Homecrest community. No house could stand on less than two lots, and no house could cost less than $1,800. Buyers did not have to put much money down, and they had a whopping twelve years to pay for their new home.

A typical Homecrest home had ten rooms. On the first floor, arranged on either side of a spacious hall, were a parlor, foyer, reception room, dining room, and kitchen. A broad stairway led to the upper floors.

On the second floor, there were typically three rooms and a bathroom. The third floor had an additional three large sleeping rooms (not sure if the bathroom on the second floor was all for the entire house.)

Most of the homes in Homecrest had a hot air furnace, and all the homes had gas. Every house had terraced, graded lawn and a full view of the Lower Bay and Atlantic Highlands. According to the ads, it was a thirty-minute, five-cent trolley ride to Manhattan.

All in all, not a bad place for a faithful, hard-working police cat to spend his life and career.