Forget the light bulb. Let’s talk about Thomas Edison’s short film starring Professor Henry Welton and his famous Boxing Cats, Sullivan and Corbett! It may very well be the first ever funny cat video (albeit, it was a film.)

In the 1890s, the renowned inventor began experimenting with a new technology–the kinetoscope–by creating a series of odd short films in his Black Maria film production studio in West Orange, New Jersey (the first in the country). The kinetoscope reproduced photographs taken at the rate of 46-per-second and preserved them in their order in a long film. Almost every major city in America had at least one theater with an Edison kinetoscope.

One of Edison’s bizarre short films was Boxing Cats, featuring the main attraction of Professor Welton’s traveling Cat Circus. Click here to watch the film.

(Edison’s studio also produced a film about the electrocution of Topsy the elephant, which was incredibly disturbing and inhumane. The cat video was not humane under today’s standards, but the elephant film would receive an R rating today for its graphic violence.)

To be honest, it wasn’t Edison who created the Boxing Cats film, but it was produced in his studio. The film was directed by William K. L. Dickson and cameraman William Heise. Reportedly, it took the men only one, interrupted try to capture the pugilist felines in their battle of the paws.

This is how Edison Films marketed the Boxing Cats film :

“A glove contest between trained cats. A very comical and amusing subject, and is sure to create a great laugh.” (by Edison Films)

Sullivan and Corbett, the cats that starred in this film, were part of Professor Welton’s Cat Circus, a troupe of up to 40 cats that rode bikes, jumped through double hoops of fire (Pasha was the calico cat who did this), stood on their heads, walked across a tight rope, rode a see-saw, shook hands, did somersaults, and pulled a fire engine to a “fire” that they put out with a hose.

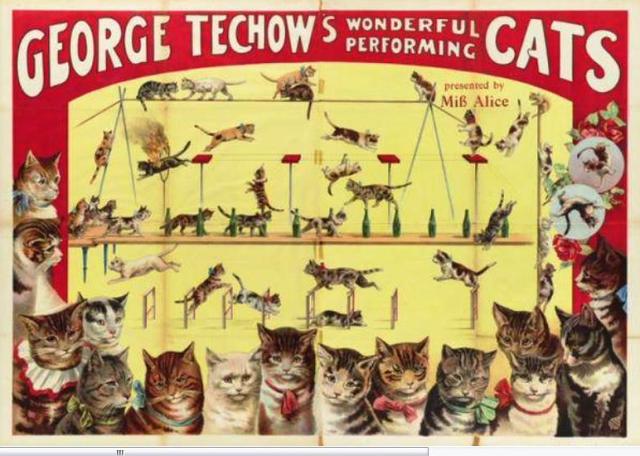

Like the cats of Professor Leonidas Arniotis’ Great Dog and Cat Circus and the performing cats of George Techow, Welton’s cats also performed at various vaudeville venues throughout the country during the late 1800s and possibly early 1900s.

The King of Cats

Henry Welton was known as the “King of Cats.” He thought that cats had a language of their own–all those cats that howled at night on back fences were in fact just having loud conversations with each other. One of his cats reportedly cost him $1000. She was so intelligent, she was able to learn every new trick right off the bat in one lesson.

Welton came from an animal-training family–all of his near relatives had trained one animal or another. In 1891, he told the press that it took him about two years to train his cats before he went public with them.

Welton explained that while the Maltese cat was the easiest to train, this breed was not strong enough to stand for all the travel and live performances. The trick, he said, was finding one very intelligent cat that would take the lead. Because many of the cats had short lives–owing to all the travel on the rail cars–he had to have a constant supply of new cats that he could train.

The most intelligent cat in Welton’s troupe in 1891 was a large gray female who could leap 10 feet and then jump through a paper hoop. The best hurdle jumper was a kitten who was Welton’s own pet–and thus was born into the business. She adored all the cats in the troupe and treated them all as if they were her own kittens.

In addition to playing the “referee” in the Boxing Cats film, Welton also made an appearance in “Cockfight, No 2” as one of the betting men, and went on to make film appearances in several other Edison films.

Huber’s Palace Museum

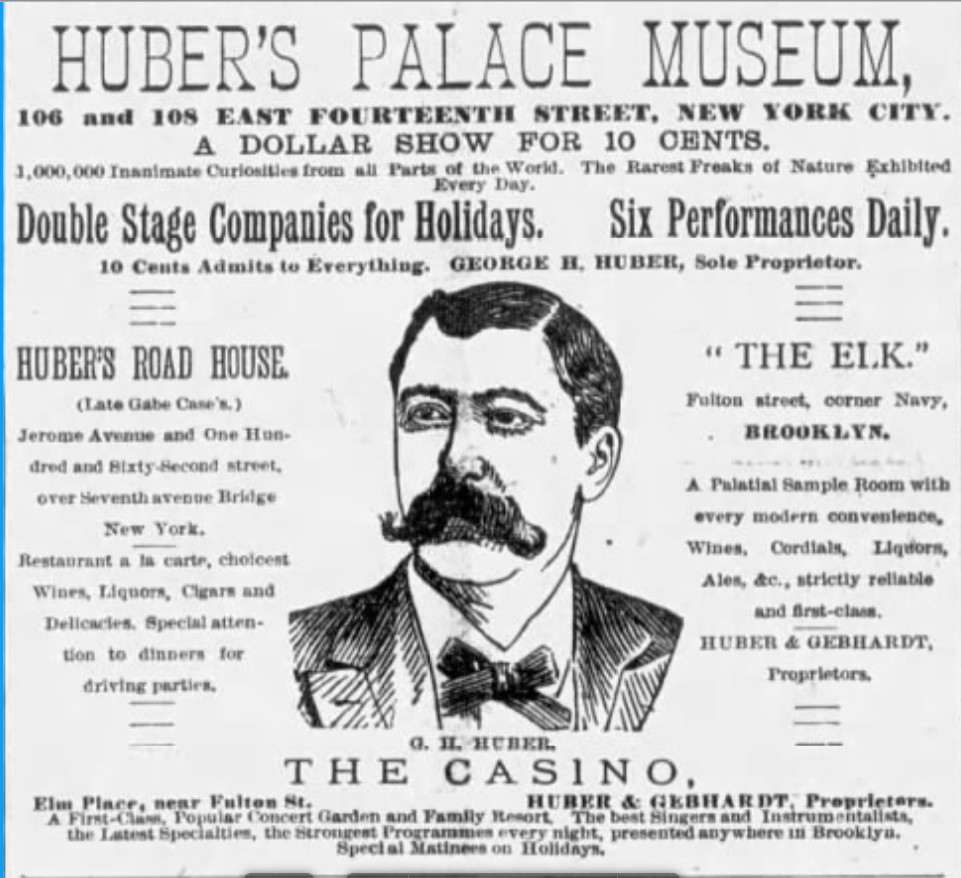

One of the venues where Welton’s Boxing Cats and cat circus performed during their American tour was George H. Huber’s Palace Museum on East 14th Street (prior to this time, Welton toured in London).

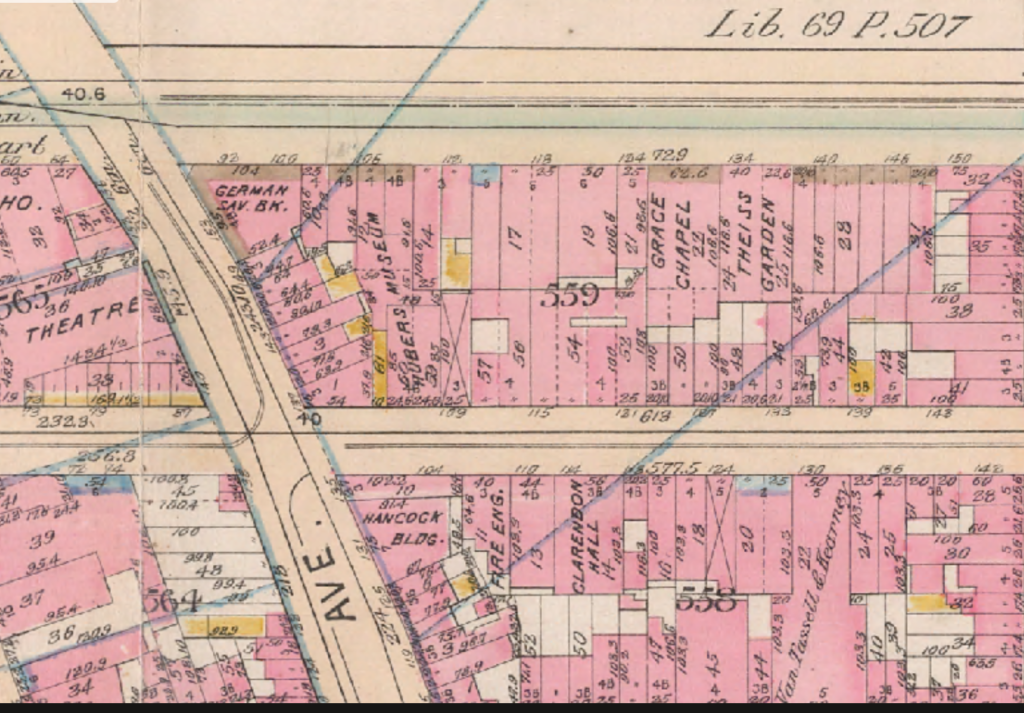

The theater had its beginnings in 1888, when Huber, a museum man from Lockport, Ohio, and his partner, E.M. Worth, a longtime showman, purchased the lease for three adjacent buildings on East 13th Street that ran through East 14th Street. The buildings, owned by the estate of Jacob A. Geisenhainer, housed boarding rooms and what was called Prospect Hall, a music hall and restaurant.

Huber and Worth knocked down the connecting walls and created a five-story, L-shaped theater that took up five city lots. The new museum featured 5,000 square feet of glass cases in eight rooms known as the Curio Hall. Most of the articles, which included old uniforms and bullets, stuffed birds, strength-testing devices, and more, had been collected by Huber during his eleven years as a museum proprietor.

The museum, which was first called Worth’s Museum, opened on August 13, 1888. The men advertised it as a museum for ladies and children looking for wholesome entertainment, and it featured a million rare curiosities and continuous stage performances from 1 p.m. to 10 p.m. Admission was a dime (hence, the term dime museum).

Some of the features during the early months included Jo-Jo the Dog-Faced Boy; Baby Bunting, the Smallest Living Horse; and Ajeeb, a mechanical chess player. On the top floors, Huber and Worth provided rooms where the performers could live with their spouses, children, and servants.

On April 12, 1890, the men dissolved their partnership, and the venue was renamed Huber’s Palace Museum (or just Huber’s Museum). Huber remodeled the museum and reopened on August 17, 1891.

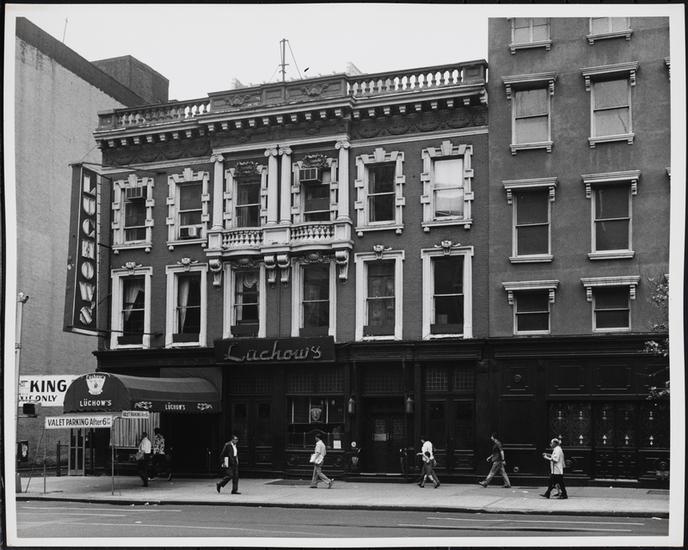

Following the 1910 season–a season which saw the death of leopard trainer Pauline Russell, who was attacked by one of her three leopards at Huber’s in January of that year–Huber sold the lease for the museum to Albert Luchow, who used the property to expand his popular restaurant, which was at 110-112 East 14th Street. As the New York Times noted in July 1910, the bottled snakes, stuffed lizards, and fat women were replaced by German food and beer.

Luchow told the press he was going to tear down the old buildings, but that does not appear to have happened. In later years, the buildings were leased to various and sundry retail establishments.

Following the sale, Huber told the press he did not know what would become of his collections, noting he would probably try to auction the items. After 33 years in the business, he said he was finally ready to retire.

The Palace Museum was not Huber’s only venture. In 1886, he purchased Gabe Case’s Roadhouse on Jerome Avenue in the Bronx for $25,000. In 1901, after having dissolved his partnership with Worth, he then expanded the roadhouse to accommodate vaudeville performances and a casino. I’m not sure if the Boxing Cats performed in the Bronx; by that time, the feline circus act may have already been a thing of the past.

On June 12, 1912, a fire caused considerable damage to a wing that had been added to the old roadhouse on Jerome Avenue. Ironically, the building was occupied at this time by a fight club where human boxers could train and compete. The main building, including the lookout tower, was not damaged in the fire.

Three years later, Huber decided to sell all of his vast holdings on Jerome Avenue, which included 56 lots between 162nd and 170th Streets. He died on June 24, 1916, at his home at 1919 Seventh Avenue. He was 73 years old.

Huber was survived by his second wife, Emma Matilda Huber (his much younger adopted daughter and niece of his first wife, Wilhelmina Schultz), and George Huber Thomson, a foster son. His estate was valued at more than $1 million. The will was hotly contested.

Thanks for another great read! Years ago (more than I’d like to say), I lived at 110 East 14th Street, now the NYU dorm University Hall. How cool to see what the area was like in the past…although I am sooooo disappointed that I never got to see the performing cats!

Oh, how cool indeed!

[…] Kar-mi. In 1894 Thomas Edison took some film of a pair of boxing cats at Huber’s, which you will find showcased on this fun website The Hatching Cat of Gotham, which has lots more details about the layout of the […]

[…] In the early 20th century, Swain’s Rat and Cat Circus featured trained cats and rats performing together. This act was part of the vaudeville scene and showcased in venues like Huber’s Palace Museum on East 14th Street. (Source: The Hatching Cat of Gotham) […]