For many years, my husband and I volunteered with Puppies Behind Bars, helping to socialize puppies in training to become bomb detection dogs or companion dogs for those in the military suffering from PTSD. We could take these dogs almost everywhere and travel with them on all forms of public transportation. So, I was surprised to find out that service dogs, such as Seeing Eye dogs, were once banned from the NYC subways.

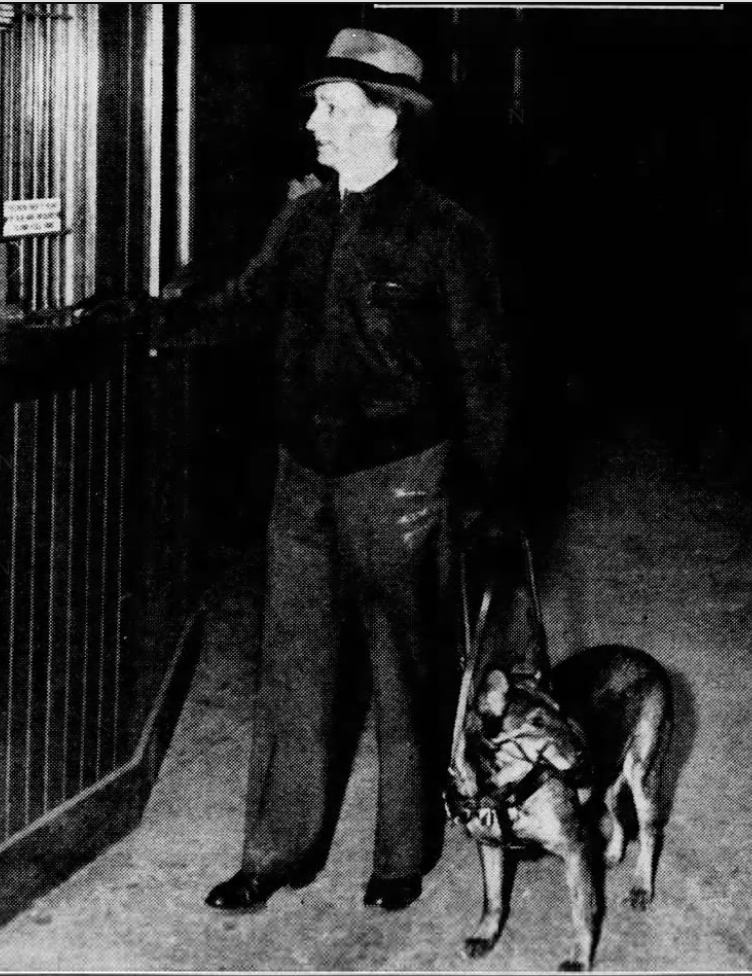

Below is the true story of Robert J. Losch and his dog, Sally, who fought to overturn the ban on Seeing Eye dogs in the subways. I discovered their story after finding the photo at left of Thomas F. Gilmartin, Jr. and his dog, Rascal.

Whenever I come across a great vintage photo like this one, I can’t resist doing some research to find out who the people and animals were. Where and when did they live? What was their story? It was while researching Thomas and Rascal that I discovered Robert and Sally and their crusade to give dogs access to the subways.

Thomas and Rascal Gilmartin

On December 5, 1940, Rascal Gilmartin, a four-legged graduate of The Seeing Eye guide dog school in Morristown, NJ, celebrated his fifth birthday. That day, a reporter from the Daily News visited the Gilmartin home at 89-17 118th Street (aka Church Street) in Richmond Hill, Queens, to meet Rascal and his human master.

For three years, Rascal had been helping Thomas attend classes at Queens College. Not only did he lead Thomas on the bus and trolley, but he also escorted him to all his classes on campus.

Thomas, a graduate of P.S. 90 and Richmond Hill High School, was studying to earn a B.S. in social service work. “I think that’s a good job for the blind, helping handicapped people,” he told the reporter. He thought Rascal would also be eligible for a diploma when he graduated in June 1941 because the dog had attended as many classes as he had.

I’ve got 100 percent confidence in him,” Thomas said about Rascal. “He’s never failed me. He practically knows my school program. When I go into a building, he knows which classroom to go to and always takes me to my seat.”

According to Thomas, Rascal remained quiet all day, and he oftentimes fell asleep during boring lectures or had the nerve to snore under the professor’s nose. The only the only time he made any noise was during assemblies, when he would bark whenever the students clapped.

Thomas, the son of Thomas and Emma Gilmartin, had been blind in one eye since early childhood. He lost sight in his other eye when he was teenager. For seven years, he could do very little without the help of others and he could only travel by himself within a three-block radius of his home.

The 25-year-old college junior told the news reporter he originally wanted to attend Brooklyn College after he graduated from high school, but he could not handle the transportation. So he had to wait a few years until he was paired with Rascal at The Seeing Eye.

Thomas had learned about The Seeing Eye on a radio broadcast. He and Rascal bonded instantly and just “clicked” from the moment Rascal walked into the reception room. “We had no trouble getting on together from the start,” he said. After a month of training he was able to bring Rascal home.

With Rascal at his side, Thomas said he felt as independent as any sighted person. “Blindness, I consider, is an affliction that was once mine, but is no more.”

To illustrate how well he and Rascal bonded, Thomas told the reporter about the time he was walking with his dog when he heard one woman say to another, “Isn’t he a nice man to lead that blind dog.”

Seeing Eye Dogs Gain Access to the Subway

To travel from his home in Richmond Hill to Queens College in Flushing, Thomas took a bus and trolley. He also relied on the bus to get into Manhattan, which could take him two hours. Thomas could not use the subway, because service dogs were banned.

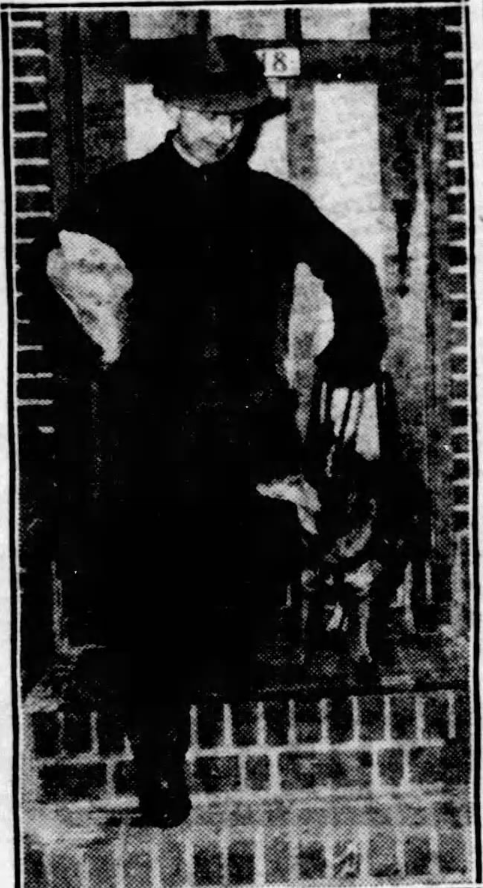

Robert J. Losch, a 40-year-old mechanical engineer who lost his sight during an auto accident in 1934, was not aware that service dogs were banned from the subways. For almost a year, Robert and his miniature German shepherd, whom he acquired from The Seeing Eye in 1939, had often traveled by subway without any objections. Then one day in February 1941, a guard stopped Robert and Sally as they were entering the 63rd Drive station in Rego Park.

“I didn’t know I was breaking an ordinance,” Robert told a reporter from the Daily News. “No one ever stopped me.”

Robert explained that Sally loved riding on the subways. She always lead him to the door once the train stopped on the platform and she never left his side, sitting on the floor next to him without making a sound. “With Sally I was safer than even a sighted person in the subway.”

Robert, who lived with his wife and 10-year-old son at 21-18 147th Street in Whitestone, Queens, was a member of the Whitestone South Community Association. When the members found out that Robert and Sally had been booted from the subway, they offered to drive him to the City Council office in Manhattan and help him get permission for Seeing Eye dogs to use the subway.

After demonstrating how indispensable Sally was to him, Robert told the council members and Acting Mayor Newbold Morris that he was not fighting for only himself. “I think there are about a dozen blind people living in the metropolitan area using Seeing Eye dogs to get around,” he said. “A change in the ordinance that forbids dogs in the subways would benefit them all.”

Two months after Robert and Sally were stopped from entering the subway, New York Governor Herbert H. Lehman signed a bill (an amendment to the Railroad Law) permitting Seeing Eye dogs on the subways and other transportation systems. On April 29, 1941, Philip E. Pfeifer, general superintendent of the subway system, issued an order stating that the dogs were permitted to ride the subways provided they were muzzled and accompanied by a blind person carrying a certificate from The Seeing Eye.

As soon as the law passed, Robert and Sally took a trip from Flushing to Manhattan, where Robert shopped for materials to make some leather handicrafts. “I put a nickel in the turnstile and went through just like everybody else,” Robert said, adding he had just as much a right to use the subways as anyone else.

Several other sight-impaired men also looked forward to using the subway with their Seeing Eye dogs. In addition to Thomas Gilmartin, who was excited about using the subway to and from school, Joseph Caronia, a Brooklyn musician who had traveled all over the country with his dog, was also looking forward to using the subways with his dog, Kion.

“It should have been done years ago,” said Lewis Smith, a well-known figure in Brooklyn Heights, where he often walked with his Labrador retriever, another graduate of The Seeing Eye. “It’s been a hardship not to be able to travel in the subway.”

One year after Robert convinced New York lawmakers to allow Seeing Eye dogs in the subway, he shattered an old hospital rule by getting permission to keep Sally by his side at Bellevue Hospital. The Daily News reported that Sally, now 5 years old, would make dog history by becoming the first dog ever permitted in the hospital wards.

According to the story, Robert suffered an attack of appendicitis on June 8, 1942. After he went to the hospital, Sally remained near Robert’s empty bed all day long and refused to eat. She began losing weight.

Robert’s wife, Madeline, took Sally to the hospital and explained the situation. As soon as the orderlies saw how intelligent Sally was, they dismissed the rules forbidding dogs. Sally gained all her weight back and then some–by the time Robert was released from the hospital, her harness was snugger than before.

“Now I hope that someday I will be called for jury duty and they’ll let Sally sit with me in the jury box,” Robert said from his hospital bed.

Robert, who had retired to Florida in 1967, passed away in May 1973 at the age of 71.

Thomas, according to the census reports, married Eleanor Habas in 1943 and was working as a supervisory trainer at the New York Association for the Blind (aka The Lighthouse) in 1950. By 1965, he was administrator of home teaching and coordinator of the Training Division of The Lighthouse and by 1971, he was the director of The Lighthouse Queens Center on Woodhaven Boulevard.

Thomas died in October 2010 at the age of 94.

Today, under the Americans with Disabilities Act, a person with a disability may be accompanied by a service dog in most public places, including courthouses. As for riding the subways, they are of course permitted (thanks in part to Robert and Sally), but there are a few subway rules for both service and emotional support animals.

If you enjoyed this story, you may also want to read about Pinky Panky Poo, the tiny dog who paved the way for the Plaza Hotel’s open door policy for small pets.