When Mrs. Harry Ulysses Kibbe and several other visionary society women organized the Bideawee home for animals in 1903, the women relied on paid subscriptions from generous New Yorkers to achieve their mission to care for friendless animals.

In its first year, the organization owned eight acres in Yonkers, but the women did not yet have a real home in the city for sheltering cats and dogs. One of their first fundraisers was a Christmas tea at the Hotel Savoy on Fifth Avenue, where raffle tickets raised $1,000 toward a permanent shelter.

By December 1905, Bideawee had a new city home in a former two-story brick stable at 145 West 38th Street, for which they paid $1,800 a year. That Christmas, the 20 dogs, 3 cats, and 1 tiny kitten living there were treated to turkey and chicken donated by the Waldorf-Astoria. The dogs also received bones and dog biscuits and shiny collars, while the cats found milk and catnip and brilliant ribbons in their stockings.

Over the years, the Christmas feast for animals became a tradition at the Bideawee home. Neighborhood children who had shown kindness during the year by bringing stray cats and dogs to the home were also invited to partake in the festivities.

In 1921, Bideawee had been in its permanent home at 410 East 38th Street for about 10 years. That year, a little boy named Johnny Anderson invited a new stray cat to the Christmas celebration.

Clutching a squirming, scrawny, angry little kitten, Johnny pushed open the door and handed the friendless cat to Mrs. Kibbe. “Take it,” he said. “I found it in the street and I wanted it to have a Merry Christmas, so I brought it to your party.”

Johnny’s face was scratched and his hands were bloody, but he was determined to bring the kitten to the holiday feast.

Johnny was a small patron of the charity organization, and he brought every stray animal he found wandering the streets to the Bideawee home. The women would either keep the strays at the home, place them with deserving families in the city, or send them to their farm in Wantagh, Long Island.

In addition to the kitten, Johnny also brought his dog, Flora, to the party. Mrs. Kibbe had given the dog to Johnny to thank him for all his kindness to homeless and friendless animals.

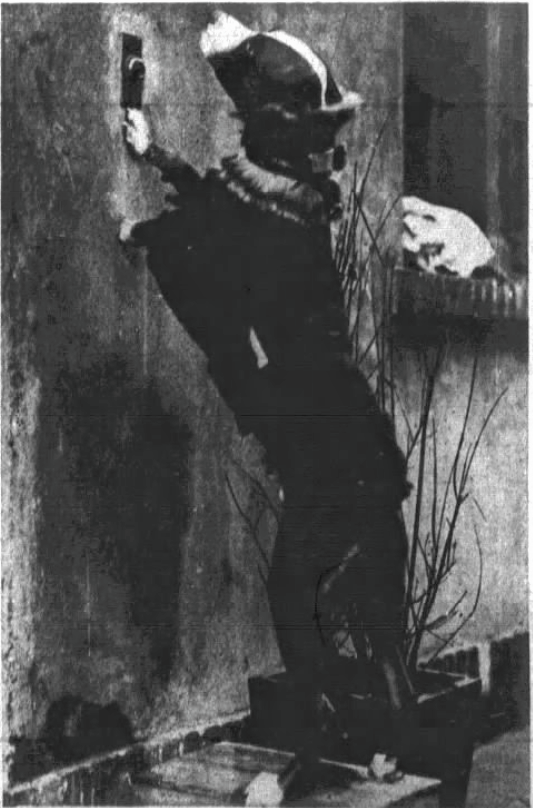

One of the resident star dogs of Bideawee during this time was Taxi, the “dog policeman” of New York. Taxi would go out on the streets looking specifically for stray dogs.

Finding a pet that had wandered far from its home and mother, Taxi would pick it up by the nape of the neck and carry it straight to the Bideawee home. There, he would step up on a box set up just for him and ring the doorbell.

Another star dog was Army, described as a “fat, black, good-natured army pet.” Army had served with the Army Expeditionary Forces in France, and he walked with “an honorable limp” due to a bullet-shattered front leg. He lived at the home, having arrived there in 1919.

On December 26, 1921, Johnny’s stray kitten and the other animal guests enjoyed a Christmas dinner of chopped meat, salmon, biscuits, and warm milk. Then they all settled down, cozy, fed, and warm, for a long winter’s nap.

The Quest for a Permanent Bideawee Home

Bideawee is the Scottish term for “stay a while.” Although Mrs. Kibbe and the other founders chose this name to evoke compassion, love, and warmth for animals in need of shelter, it was also an appropriate name for the organization during its first eight years, when the women were forced to move from home to home in their quest for a permanent “no kill” shelter.

In 1911, Bideawee moved three times. The third move was the charm.

The quest began in 1903, the year Bideawee placed more than 400 dogs and 75 cats in good forever homes. Their own home at this time was a temporary place in a five-story building at 118 West 43rd Street.

One of the women’s biggest opponents at this time was the ASPCA, which insisted that unwanted animals be turned over to the society to be put to death. This opposition often made it difficult for the ladies to win over supporters of their cause and raise enough funds. But they were persistent.

Following a few years in their next home on West 38th Street, the ladies move to 36 Lexington Avenue, where they stayed until March 1910. The prior year, the Board of Health had ordered the women to remove all the dogs from Lexington Avenue (they were sent to a 10-acre farm in River Vale, New Jersey); the building was also too small to accommodate the cats.

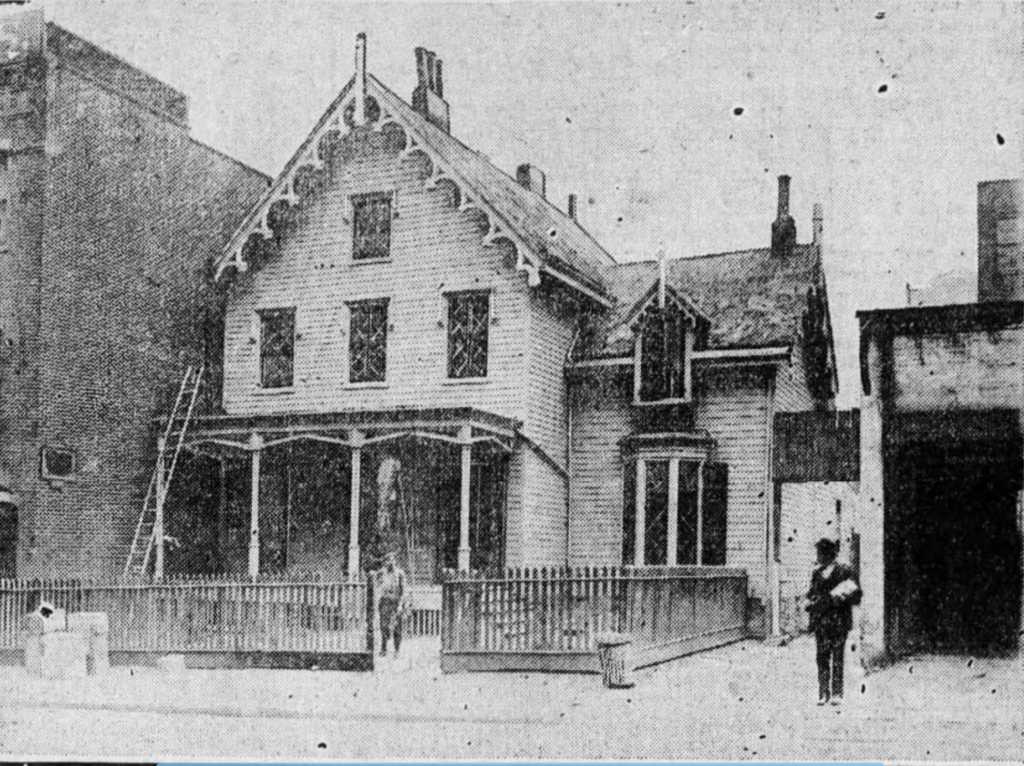

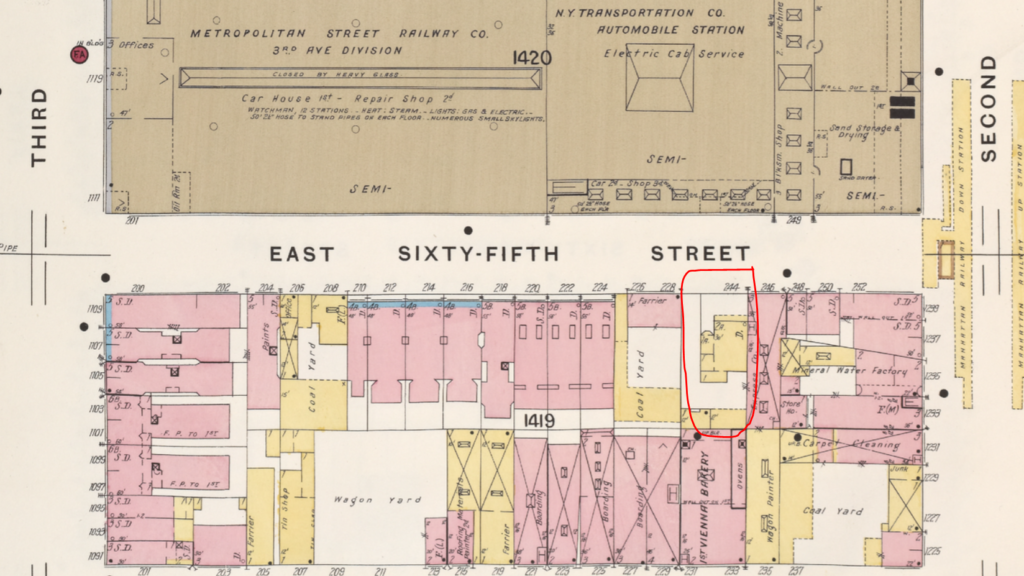

In March 1910, Bideawee purchased from Thomas Lownden a long-term lease on a two-story and attic frame house and stables at 244 East 65th Street. The 100-year-old, 13-room house had once been a mansion, but was now surrounded by an express office, blacksmith shop, and coal yard; the Third Avenue Elevated Railroad power house was across the street.

Mrs. Kibbe said the environment was ideal, as there were no close neighbors to complain about the barking dogs and howling cats. As the New York Times noted, “Even the strongest-lunged tomcat or the most obstreperous wolfhound will be able to make as much noise as it likes without a protest in any direction.”

In addition to the large house, which Mrs. Kibbe said would be able accommodate twice as many animals as the building on Lexington Avenue, there was a large stable in the rear yard, which would provide shelter for the larger dogs. Mr. Lownden, a coal dealer and amateur dog fancier, had also gone the extra mile to erect a new fence around the front yard so the animals could go outdoors for exercise.

Inside the home, Mr. Lownden repaired some of the rooms to make the animals as comfortable as possible. New wire cages were installed and an outdoor wooden staircase was built from the upper floor to the yard for the dogs.

Ironically, only one block away from the new Bideawee home, at the foot of East 66th Street, was the Rockefeller Institute, which used animals for experiments in vivisection. The institute paid children 25 cents a head for stray dogs and half that much for stray cats.

When asked if Bideawee planned on competing with the institute by paying children more money for stray animals, Mrs. Kibbe told a New York Times reporter that there were no such plans to compete.

However, she said, Bideawee did plan on establishing clubs in which the neighborhood boys would be given lessons on how to be kind to animals. Buttons and medals would be awarded to those children who helped save the animals rather than sell them for cruel experiments.

By November 1910, the women were in trouble again. Although they had paid off their mortgage on their farm in River Vale, they were still short $5,000 needed for other expenses. Their workhorse, Dandy, who did a lot of work on the farm, had also taken ill. Then their automobile ambulance was run down by an ash cart and wrecked.

The situation became even more dire when the women learned that they had to vacate their new home on April 10, 1911. Mrs. Kibbe told a reporter that they thought they had secured a 30-year lease for the property. However, Mr. Lownden had to release his property rights to an express company that wanted to put another express office on the site.

Although an adjacent home was available, the Board of Health would not allow Bideawee to move into that building because it was within 100 feet of a tenement building.

At the time that the women received this bad news, they were housing 250 dogs and cats and one horse named Diamond.

“We have tried in vain so far to find a new city home for the animals,” Mrs. Kibbe told a New-York Tribune reporter on April 3. “Everyone objects to them being near private houses and tenements.”

On April 8, two days before they had to leave, Bideawee secured a temporary lease from real estate tycoon Felix Isman in a building at Broadway and 47th Street. About 100 dogs were sent to the New Jersey farm, and a receiving station was put in place on East 65th Street so the society could continue receiving animals from the boys in that neighborhood.

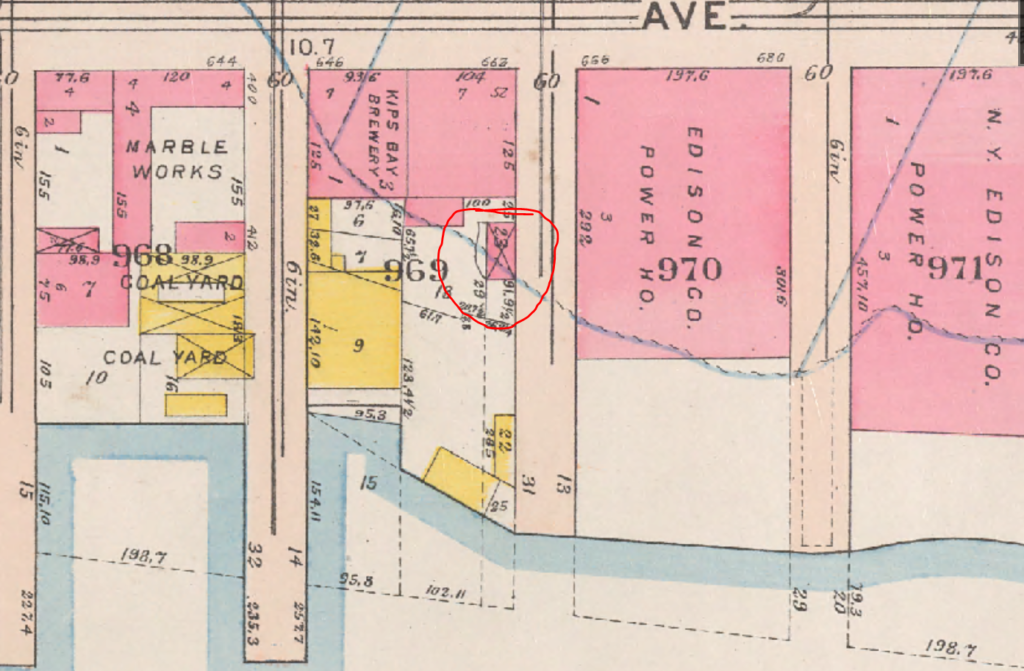

Finally, in October 1911, the women found the perfect “furever” home where there were no neighbors to complain of barking dogs and yowling cats. The two-story building at 410 East 38th Street, which had once been the site of stables for the Kips Bay Malt Company, was surrounded by the Edison Power Company, Kips Bay Brewing Company, razor factory, and coal yard.

Bideawee leased the large building and property from the estate of Mary Jones, a descendant of brewer David Jones, who had purchased the former brewery property for $80,000 in 1872.

The two-year lease included an option to buy, which Bideawee exercised, resulting in a $50,000 mortgage. The final pay-out of $8,000 was due January 1, 1922, just one week after little Johnny Anderson brought a stray kitten to the Christmas party.

If you enjoyed this Christmas animal tale of Old New York, you may like reading about Paddy Reilly, the Irish terrier host of New York’s annual Christmas party.