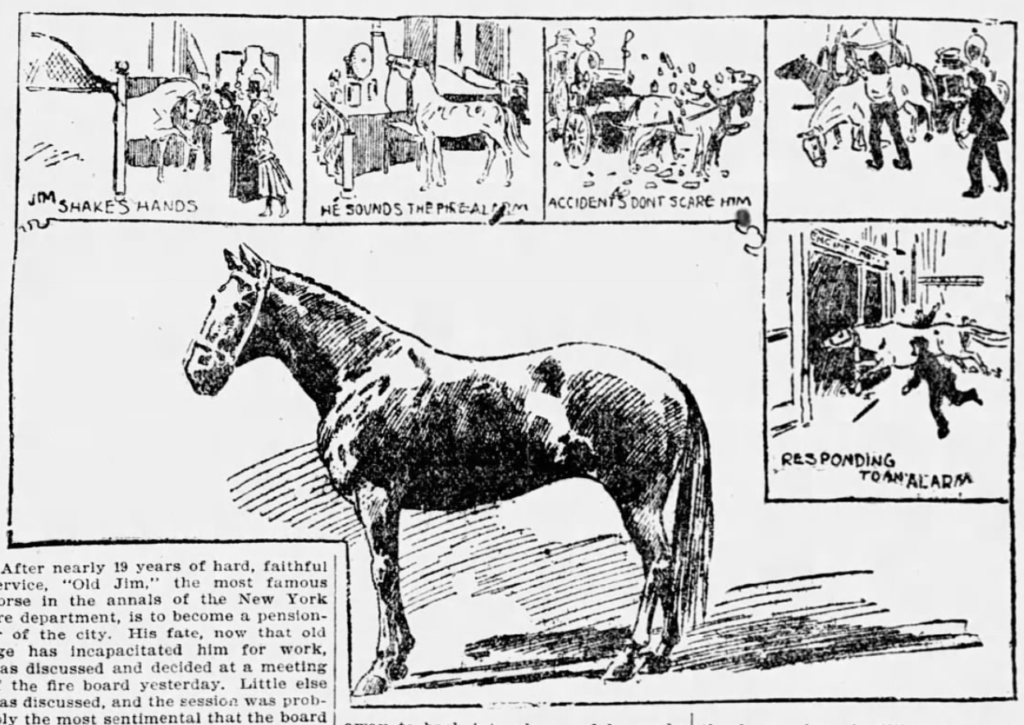

Under the 19th-century rules of the Fire Department of New York (FDNY), when horses were no longer fit for the hard service of pulling engines, hose reels, or ladder trucks, the department would sell them at auction to any huckster that needed an old horse to pull his cart or do his dirty work. But no such fate was to come to Jim—at least not if Chief Hugh Bonner or Engine 33 Captain William H. Nash had any say in the matter.

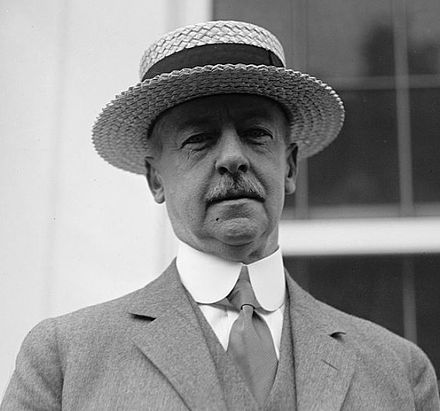

Jim was a large (1,500 pounds) strawberry roan of thoroughbred pedigree, born in Kentucky and thought to be related to Norman, the famous racehorse of American financier August Belmont Jr.

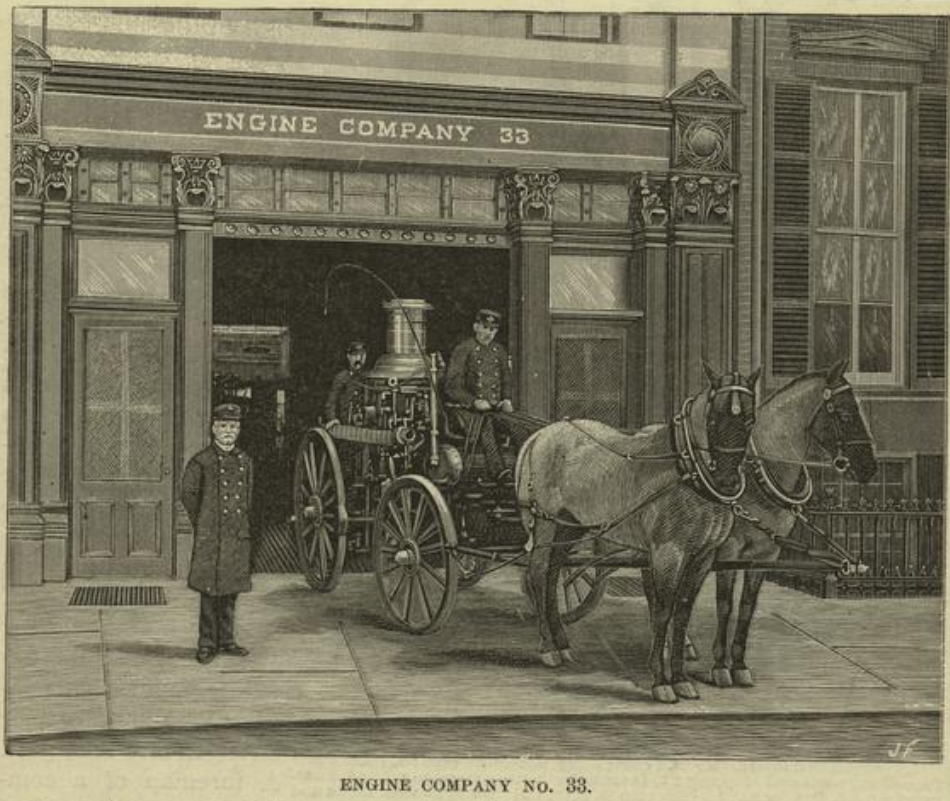

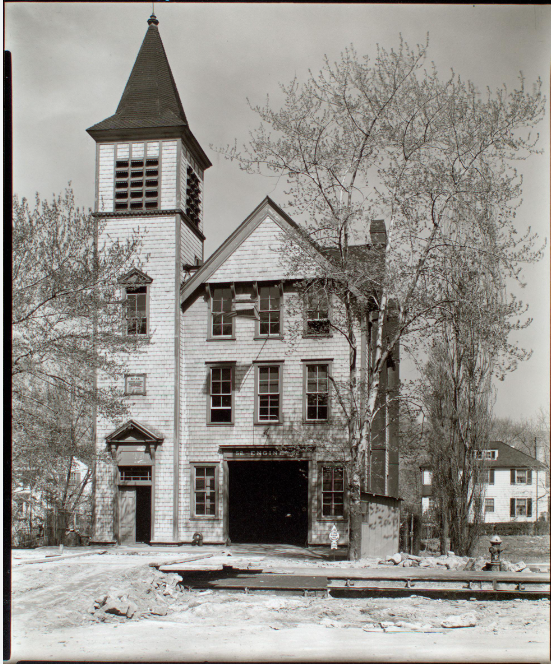

Officially known as registered horse No. 60, Jim began his FDNY career with Engine 33 on Great Jones Street on January 14, 1879, when he was about seven years old. He remained on active and reserve duty for nearly nineteen years until November 4, 1897. For eleven of those years, Jim and his mate drew a heavy first-class engine—the type that in later years was drawn by three horses. Jim was always the off-side horse, meaning he took the right side of the engine.

During his long FDNY tenure, Jim wore out several mates that could not keep up with him. Should the nigh (left) horse loaf around, Jim would turn toward him—even while in full gallop—and nip at the other’s neck to admonish him for goofing off on the job.

One of the few horses that worked well with Jim was another strawberry roan named Jack. Sadly, Jack died while responding to an alarm in May 1881 when the team collided with the Engine 13 tender. A pole plunged twelve inches into the horse’s body, fatally wounding him.

The company replaced this fallen horse with horse No. 350, whom they also named Jack. Jim and his new partner pulled the engine, and a horse named Jerry drew the tender. The men called them “the three Jays.”

Jim and Jack achieved fame and publicity on October 26, 1883, when they took first prize in the hitch-up drill at the inaugural National Horse Show at Madison Square Garden. The pair beat the competition by hitching into a swinging harness in just under two seconds.

During the show, high-society ladies stroked Jim’s arched neck and millionaires pointed to his muscular flanks and powerful legs while commenting on his massive proportions. Following the event, Engine 33 became a popular place for visitors who had read about the horses and wanted to reward them with sugar cubes.

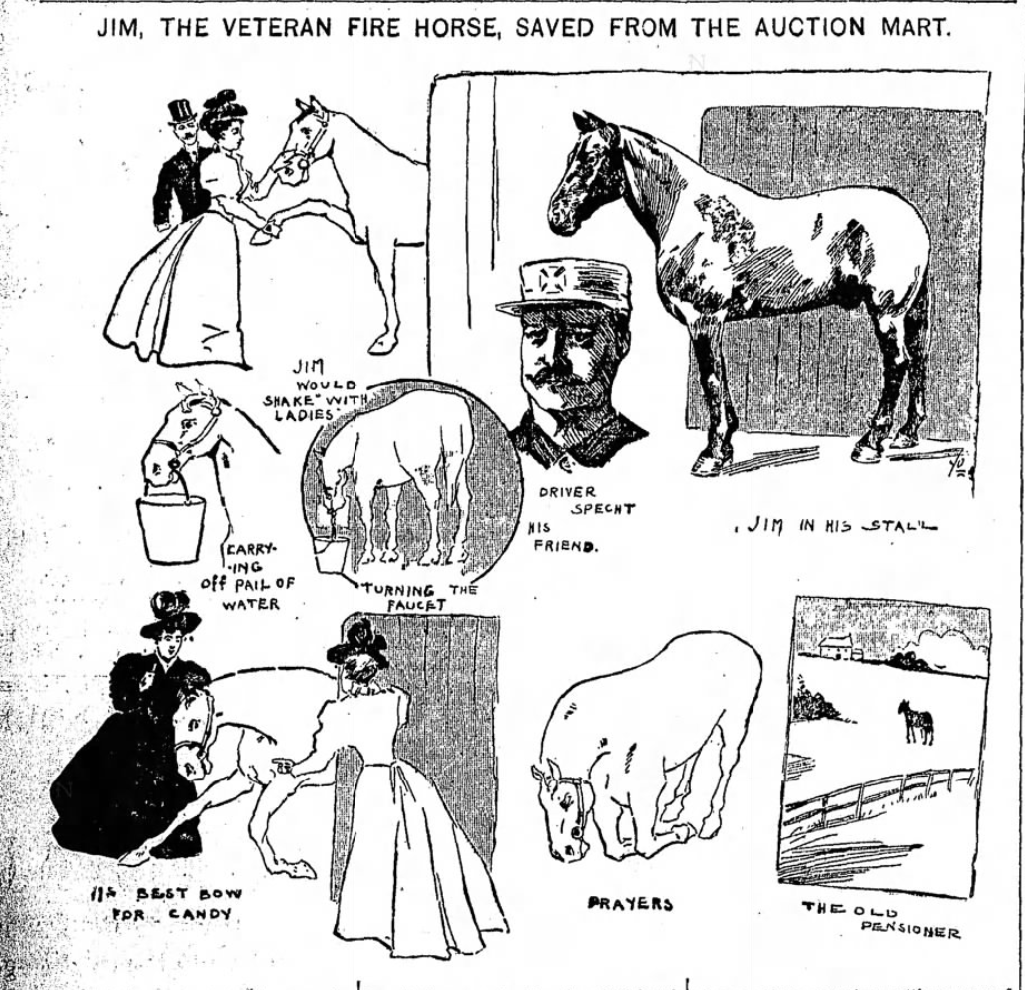

Sometimes Jim would perform some of his tricks for the visitors, such as “shaking hands,” bowing for candy, and kneeling in a prayer position.

Jerry was also a massive horse at 1,700 pounds. The coal-black horse began his FDNY career with Ladder 7 (Truck 7) in 1876, when he was four years old. He transferred to Engine 33 in 1881, where he earned recognition for his “pluck, strength and ambition.”

One of his greatest feats was pulling the tender on the first night of the Great Blizzard of 1888. On that night, he pulled the tender for one and a half miles, keeping up with the two-horse engine and passing four-horse tenders stuck in the snow.

At times during the storm, Jerry pulled the tender through drifts that were higher than his head. When the engine got so far ahead that it was out of his view, he grew frantic and strained every muscle to catch up with Jim and Jack.

In December 1889, Engine 33 was called out to a small fire at the New York Hotel. There was no urging required from Driver William E. Wise as Jerry pulled the 7,200-pound tender with 10 men aboard down Great Jones Street and up Broadway.

But as Jerry reached Fourth Street, Fire Patrol 2 came racing down that street, whereupon the two large pieces of apparatus collided. The iron tip of the patrol wagon’s pole plunged six inches into Jerry’s chest.

The driver for the patrol wagon backed up his team to extract the pole from Jerry, who continued to the fire as the blood streamed from the hole. The tender was the first to reach the fire; Jerry was immediately unhitched and led to the department’s horse hospital at 199 Chrystie Street, where veterinary surgeon Joseph Sheehy dressed the horse in large bandages. Jerry was expected to recover following a two-month respite.

The final fates of Jerry and Jack are not known, but Jim continued his storied career with Engine 33 for several more years, under the care of Driver Charley Specht. Although Jim retired from active duty in 1891, he remained on reserve duty with the dual company’s second section engine until 1897. Calls for the second section were relatively rare, so Jim reportedly acquired a taste for beer and chewing tobacco during this slow period of his career.

Jim’s last day of duty was on November 3, 1897, when he helped pull the engine down to Chambers Street. The horse alongside him was a spare horse known to loaf, and Jim–who was nearly blind at this point–began biting the horse’s neck while galloping in style down the street.

Following this last run, Captain Nash sent Jim to the horse hospital. There, he grew restive and depressed from being away from the action and the sound of the fire gong. When he refused to take his feed, the captain sent Driver Specht to the hospital two or three times a day. Jim would always welcome Specht and eat whatever he placed before him.

In a letter that Captain Nash penned to the Fire Board to request that Jim be allowed to retire with dignity, he wrote extensively of Jim’s intelligence. All the officers and members connected with the company, as well as many distinguished guests who visited the quarters, had expressed the belief that no other horse showed more intelligence than Jim.

At the sound of the gong, Nash wrote, Jim would bound from his stall at full speed and slide along the floor as much as eight feet before stopping directly under his harness. Whenever the men turned him loose on the street for exercise, he would immediately return to his proper place under the harness should the gong sound. He never missed a day of work, and even when showered with broken glass or other falling objects, or deluged with water from a broken hose, he kept on working undisturbed.

“There was never a horse connected with this department who performed so much hard service as faithfully as poor old Jim, to say nothing of the pleasure he gave the many visitors at these quarters by his actions, which showed almost human intelligence,” he concluded.

Chief Bonner also wrote a letter to the board, stating that he fully endorsed the captain’s letter while reiterating the opinion that Jim was one of the most intelligent horses in the department.

“I appeal to the board on behalf of this faithful animal that he be retained in the service of the department and assigned to some company where the duties will be light, and that the Superintendent of Horses be directed to not include in his sale registered No. 60, which is the number assigned to this faithful animal.”

Engineer Hugh Burns, who had been in his position since 1869, did not write a letter about Jim, but he did wax sentimental about the beloved horse at the board’s meeting on November 19, 1897. With “an affection for the horse as deep and great as the friendship which exists between man and man,” Burns bragged about all the tricks Jim could do, noting the horse was “like a little child at school” when he was a youngster.

According to Hughes, Jim could turn the faucet on when he wanted water and pull the alarm gong before the attendant could reach it (before the days of electricity, when the gong was rung by hand). He could also distinguish between the men he worked with that he liked and those he disliked.

The letters and speeches worked. The fate that met almost all of New York’s four-legged firefighters was not to be his. Instead of the auction block, Fire Board President James Rockwell Sheffield ordered that Jim be saved from the milk or grocery wagon.

As the horse was old enough to retire on a pension, Sheffield sent Jim to a firehouse in the Bronx (reportedly Engine 52 on Riverdale Avenue), where he would spend his remaining days in green pastures and his nights in the comfort of the quiet firehouse.

“He will feel strange up there in the country, so far from his old engine-house,” Nash told a reporter from the New York World. “You know, an old horse like that, when he finds himself put away, is like an old man retired from business. He potters around for a while and then breaks down altogether, because he has nothing to keep him interested in life.”

Nash said he was sure the horse would receive good care, but he felt certain Jim’s heart would eventually break if he could not answer any more fire alarms.

As of 1902, Jim was the only FDNY fire horse to receive a pension. According to the New York Sun, he lived at the Bronx firehouse for the rest of his life, nibbling the grass along the country lanes and doing tricks for the firemen.

One day the men found Jim in a heap near the firehouse, stricken with paralysis. An officer from the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) humanely dispatched the old horse to put him out of his physical and mental misery. He would have been about 30 years old.