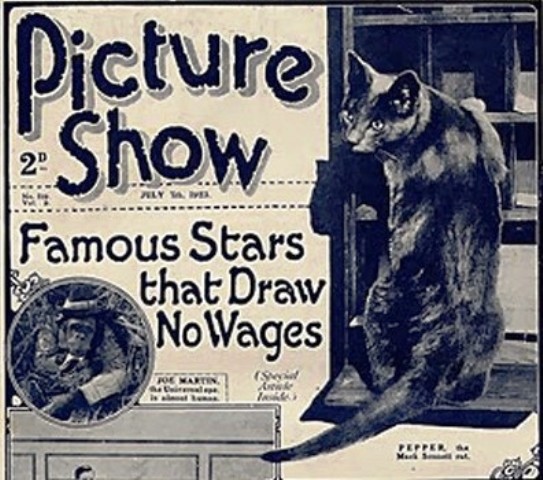

“A Corner in Cats” Was Filmed at the Gaumont Company Studios in Flushing, Queens

When Edwin Middleton, director of the Gaumont Company studio’s comedic moving picture “A Corner in Cats” needed dozens of feline extras for the film, he turned to the streets of Flushing and the Bideawee home for animals in Manhattan. He had already hired every professional “movie cat” available at the rate of five cents a day (perhaps he rented these cats from Miss Elizabeth Kingston, who ran a cattery called “Kingston Kattery” in Richmond Hill from which she rented trained cats to film studios).

But the director was still about 100 cats short.

Although vaudeville dancer and silent comic film actress Cissy Fitzgerald received top billing, the real stars of “A Corner in Cats” were, well, the cats. Without adequate felines, the film would have been a flop.

In the film, two enterprising crooks (played by Fitzgerald and comedic actor Bud Ross) go to a town called Boomopolis, where they rent a large public hall. There, they place a sign stating they will pay 50 cents for cats. Then, they order 600 rats to be delivered to the town.

The townsfolk become so desperate to rid the city of rats that they agree to pay the crooked couple $15 for “choice mousers” and $10 for “ordinary cats.” Even those who sold a cat for 50 cents are willing to pay the exorbitant prices to buy them back. As the couple is leaving Boomopolis with their earnings, they pick up a stray cat that they adopt and name him Cash.

In order to meet their demand for movie cats, Middleton and the other studio managers placed notices in Flushing advising the public that the studio was in need of all kinds of kitties and was willing to pay and care for them during film production. After the moving picture was made, the Gaumont Company studio would return the cats to their rightful owners.

No surprise, as soon as the neighborhood children learned that the studio was prepared to pay for cats, a large procession of boys carrying all kinds of stray felines made its way to the Gaumont Company studio on Congress Avenue (today’s 137th Street) in Flushing, Queens.

Even with the influx of Flushing street tabbies, Edwin Middleton still needed about 45 more cats for the picture. So, he telephoned Mrs. Harry Ulysses Kibbe (nee Flora D’Auby Jenkins), founder and president of the Bideawee home at 410 East 38th Street in Manhattan. Mrs. Kibbe offered to supply the cats to the studio at no charge, provided the cats were returned to her in the same good condition.

And so “forty-five cats, black, white, yellow, gray, slim and fat, old and young, left their happy home at Bideawee…and went out in a big automobile to the Gaumont studio.”

I cannot begin to imagine the scene on the set with more than 100 stray and shelter cats–my house is chaotic with only three domestic cats. So one can only hope they all returned home in good condition with no bites and scratches, and every whisker still in place.

This concludes the cat story, but if you’re interested in New York City history, please read on. The location of this sweet cat tale has ties to secret tunnels in College Point that may have once served as a stop on the Underground Railroad.

The Gaumont Studios at Flushing and College Park

The Gaumont Company established its American studio for processing moving picture films in Flushing, Queens, in 1909. That was the year French inventor Leon Gaumont applied for his first patent for what was called a Gaumont machine.

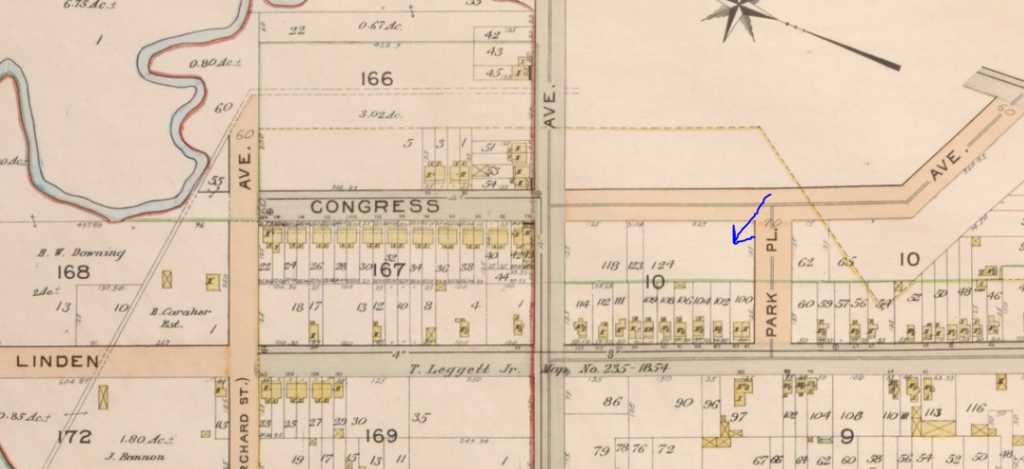

In April 1909, the Gaumont Company purchased 14 lots on the west side of Congress Avenue (137th Street), north of Park Place (today’s Latimer Place, named for inventor Lewis Latimer). The company erected a rudimentary summer studio with frontage on Park Place (a winter studio was established in Florida).

In 1915, the Gaumont Company purchased several additional large tracts bounded by Linden Avenue (Linden Place), Myrtle Avenue (32nd Ave), Congress Avenue, and Park Place. With the goal of creating the largest moving picture plant in the East, they tore down all the old buildings, including an open-air stage and staff houses, and replaced them with several new buildings.

The new facilities, which included an all-year studio on Linden Avenue (where several companies could work at the same time under glass and artificial light), allowed Gaumont to produce frequent releases of five-reel features known as Mutual Masterpieces.

Now, here’s where the historical part of this story gets interesting.

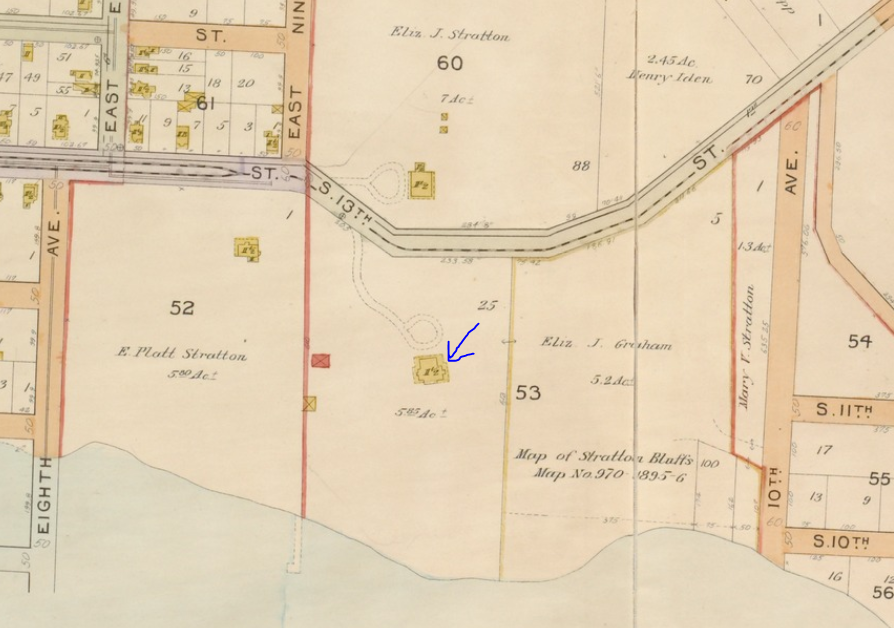

According to a one-paragraph article published in The Billboard on May 23, 1914, the Gaumont Company acquired a 10-acre plot between Flushing and College Point, in an area called Stratton Bluffs, where they erected a large stage for outside work. There was a 24-room mansion on the property, which the company used as a background in the moving pictures and also for dressing rooms, offices, etc.

Perhaps it was here that “A Corner in Cats” was filmed, but I can’t prove that. However, the nondescript mansion intrigued me, so I did some digging and came up with some fascinating historical information about Stratton Bluffs and the mansion itself.

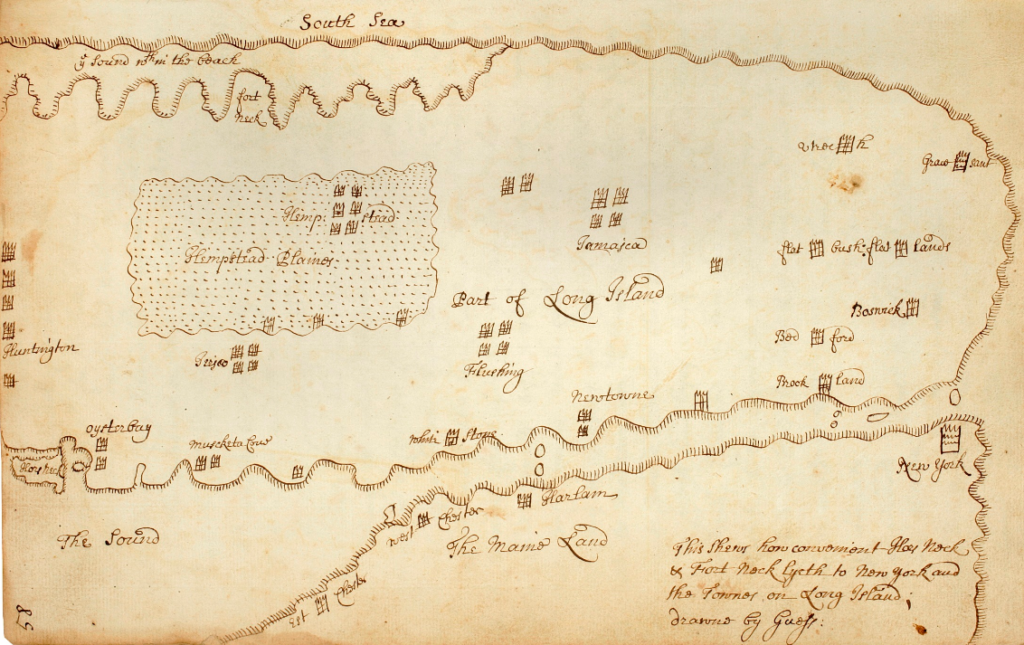

The story begins with the Lawrence family, who, along with the Parsons, Willets, and Bownes, were Flushing’s most prominent settlers during the Colonial period. These settlers, who were religious dissenters from New England, were granted a patent from New Netherland Director William Kieft for the town of Flushing in 1645.

The Lawrences served the American cause during the Revolutionary War, so when the British captured New York City in 1776, the troops destroyed much of their property. Following the Revolutionary War, the Lawrences began selling off their land to pay off their debts. The Strattons were the first family to begin purchasing this land.

One of Flushing’s first settlers and patentees was Captain William Lawrence, a ship captain who received about 900 acres of land from the 17,000 acres previously owned by the natives (the Matinecock Tribe) in 1645. He settled on a piece of land called Tew’s Neck, which he renamed Lawrence’s Neck. Tew’s Neck encompassed all of today’s College Point.

According to the New-York Historical Society, William Lawrence owned one indentured servant–an English boy named Bishop–and 10 African slaves who had likely arrived in Flushing through trade with the West Indies. Lawrence was not the only slave owner in Flushing: a 1698 Flushing census notes that there were 113 enslaved Africans in a town of only 530 Europeans.

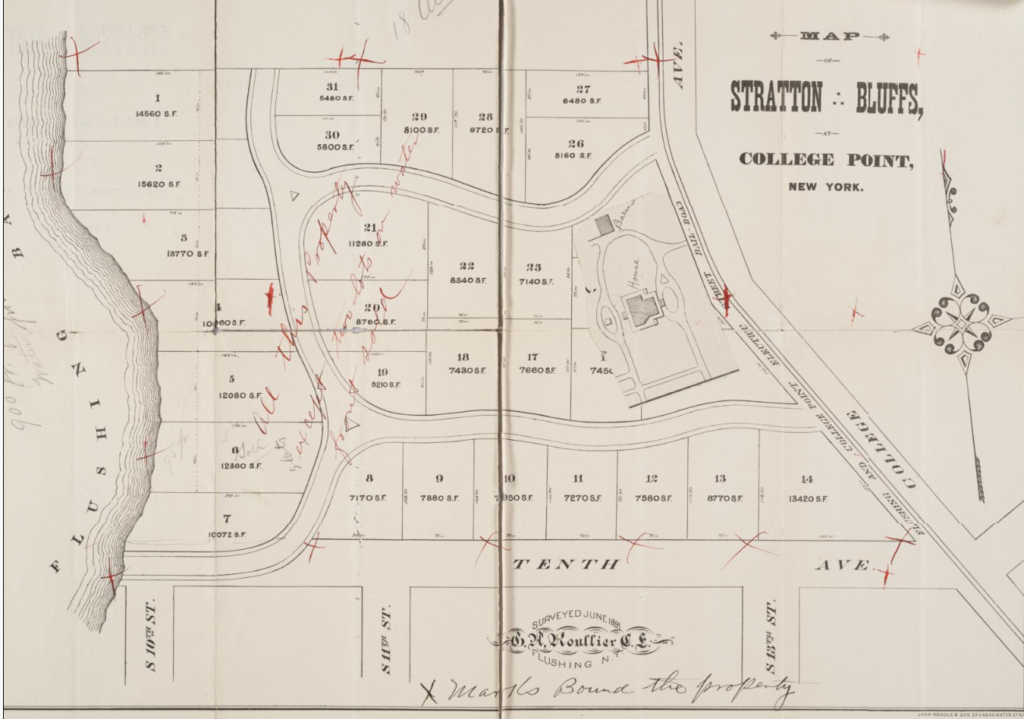

Fast-forward 100 years to about 1787, when Eliphalet Stratton and his wife Mary Valentine moved from their home in Huntington, Long Island, to Lawrence’s Neck. There, they purchased the the Lawrence farm from Abraham Lawrence. The farm was thereafter called Strattonport. (A large part of the farm was laid out into village lots and incorporated as College Point sometime around 1857.)

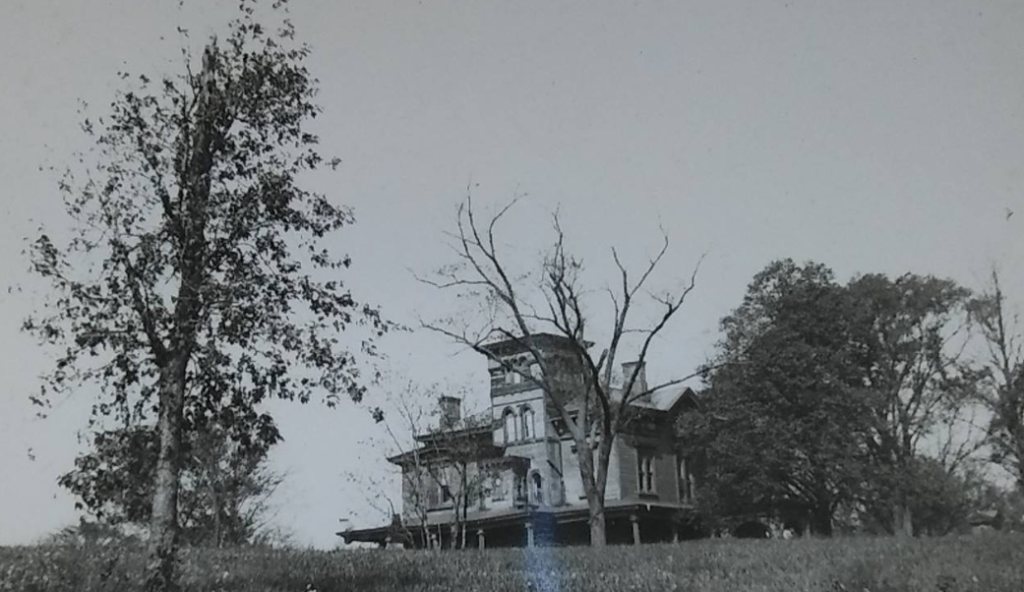

Eliphalet and Mary lived in the home pictured below, which they built on Stratton Bluffs in 1792 near present-day College Point Boulevard and Graham Court.

The Strattons had eight children, including a son name Platt, who inherited the entire estate when Eliphalet passed in 1831. Platt, a shipping magnate, and his wife, Elizabeth Hewlett Jones, had four children. Their daughter Elizabeth married a wealthy English ship master named Captain John Graham.

The mansion that the Gaumont Company purchased to make moving pictures was in fact the old Captain Graham mansion.

According to news reports and a 1989 architectural/historical report prepared for the Landmarks Preservation Commission, Captain Graham came to America in 1832 and built the mansion sometime around 1861. The mansion was located on 14 acres of land bounded by present-day 26th Avenue and Graham Court between 121st Street and College Point Boulevard. The estate also included 15 acres of land under water.

Graham reportedly established a farm on his land. According to the 1870 enumeration, he had four horses, two milk cows, four pigs, and four other cattle on his property.

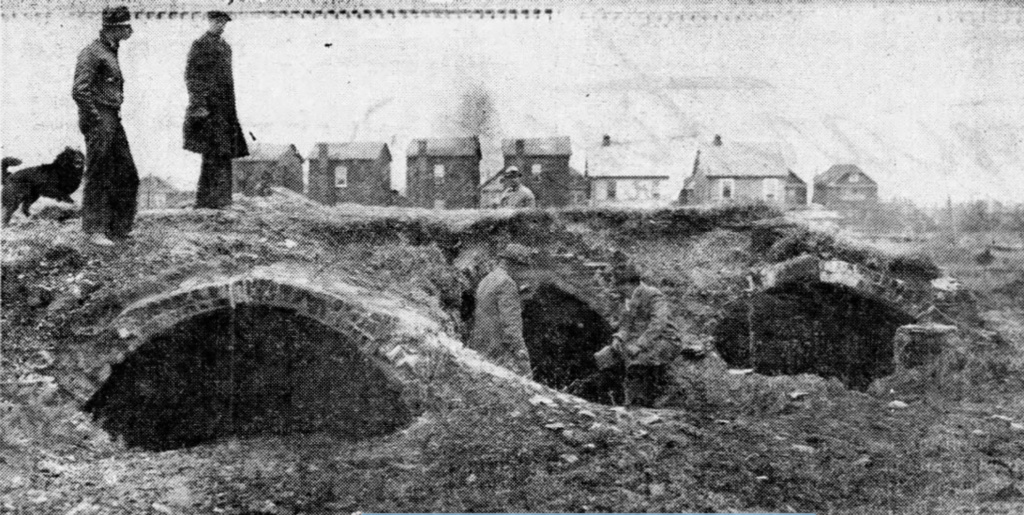

One of the features of the estate was a series of brick vaulted caves and tunnels that led from the house to the waterfront. It is reported that there may have been a fireplace in the mansion’s basement which swung open to reveal a manhole leading to these tunnels.

Graham was now a farmer, so perhaps he used the caves for storing produce before shipping it out. Or maybe the tunnels served as a vast wine and spirits cellar.

Interestingly, one rumor suggests the tunnels were used by smugglers to avoid British taxes during the Revolutionary War. If that were true, the tunnels would have pre-existed the mansion by about 90 years.

Other rumors accused Graham of participating in the slave trade; however, according to an article published in the Brooklyn Times Union in 1927, Graham did not trade slaves but rather helped them escape to Canada. This article and other reports suggest that the tunnels may have been a stop on the Underground Railroad. The theory was never proven, but it’s quite feasible given the timeline.

Whatever the tunnels’ intended purpose, local boys reportedly used them as a shortcut to get to the beach on Flushing Bay.

Captain Graham resided at the mansion for about twenty years until his death on March 30, 1882. Manhattan banker Bernard J. Burk lived in the home next, followed by Dr. Paul Kyle, who used the mansion as a boarding school for boys called the Fuerst Institute after his first institute burned to the ground in 1891.

In 1901, the mansion became a private sanitarium, Knickerbocker Hall, operated by Drs. Sylvester and Smith. Seven years later, a Manhattan and Philadelphia realty syndicate purchased the property from Elizabeth J. Graham for $100,000. Plans included a high-class residential park with a wharf and casino. These plans obviously never came to fruition, because in 1914 the Gaumont Company was using the mansion for its moving pictures.

Sometime around 1917 the mansion was razed. Then in 1927, an auction took place to sell the property, which had been cut up into about 150 building lots.

The auction block was set up on the flagstones that once formed the doorsteps of the mansion. In addition to these flagstones, the four gate posts that marked the entrance to the estate, as well as a hand-wrought iron gate, were still standing. The old barn was also still standing, albeit its roof had been lost in a fire.

It was while men were laying out the building sites and cutting through streets that the old secret tunnels were discovered. If I lived in one the houses now on the site, I’d start digging…