Missing Kitten Creates a “Cat Line” Down Lexington Avenue in Kips Bay

Two days after the pet kitten of Dr. Charles Neal Leigh and his wife Mollie Carpenter disappeared from their Kips Bay apartment at the Wareham on Lexington Avenue, Charles placed an ad in the newspaper. The ad was supposed to say that he was offering a $5 reward “for a tortoiseshell long haired kitten.”

Imagine his surprise when he opened his newspaper the following day to find that he was offering a $500 reward! That’s some expensive typo.

Several reporters went to see Charles about the grand reward. Not only did he refuse to answer questions, but he also wanted to know “who in thunder could believe that any cat was worth $500.” (Charles was obviously not a true cat man.)

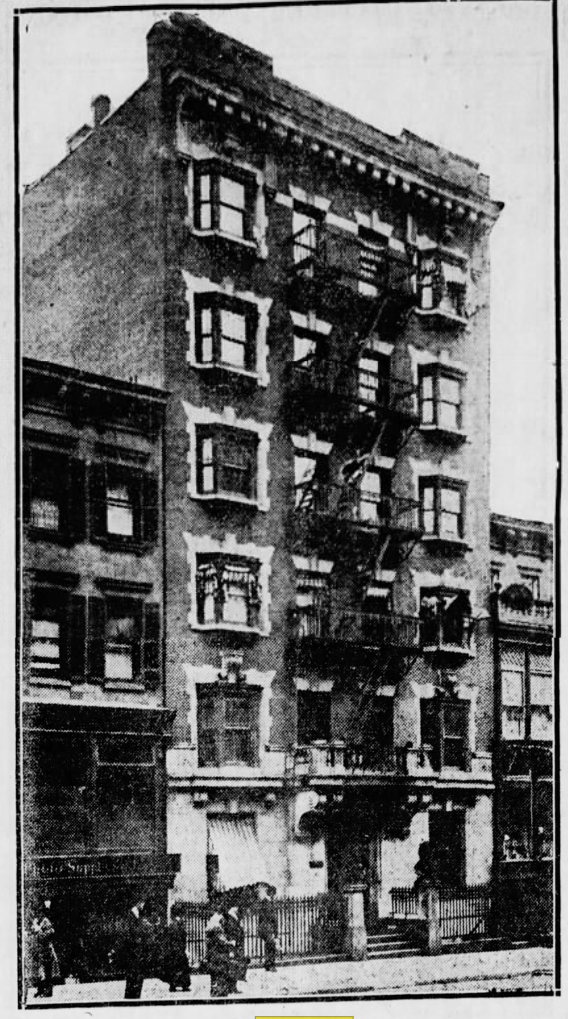

The kitten may not have been worth $500, but in 1907, but she was living in middle-class style at the new Wareham apartments at 231-233 Lexington Avenue, on the northern edge of Manhattan’s Kips Bay neighborhood.

Designed by architect James E. Ware and built in 1905, the Wareham attracted the professional upper middle class who were priced out of the more luxury buildings rising up in mid-town Manhattan. The $40,000, six-story, red brick building featured an elevator and three flats per floor, for which residents could pay about $600 to $900 a year for three, four, or five rooms.

Charles Leigh was a druggist and chemist who specialized in perfumes and women’s toiletries. In 1890, he founded his own company, Leigh’s Cosmetics, which was acquired by the Shulton Company around 1943. According to Cosmetics and Skin, Charles’ company may have developed the fragrances used in Shulton’s Early American Old Spice, Early American Friendship’s Garden and Desert Flower lines.

Aside from his perfume company, Charles’ other “claim to fame” was losing a lawsuit in 1902, when Poland Spring Water charged him with re-filling their bottles with tap water and re-selling them in his Park Avenue Hotel drug store. He received a $250 fine and lot of publicity for this incident, which is perhaps why he shunned the reporters who tried to interview him about his missing kitten.

The Angora kitten, described as a chestnut-brown cat with kinky fur, shared the family’s apartment with a fox terrier named Jimmy (the Leighs, who married in 1891, did not have any human children).

According to the New York Sun, “The gossip of the Wareham was that the dog…was treated with more consideration than most children. He wore a coat of Persian lamb’s wool and little boots to keep his feet dry and warm in inclement weather.”

The Angora kitty was reportedly the smartest cat on Lexington Avenue. And Jimmy was also famous throughout the neighborhood. One of the pets’ biggest fans was the family’s West Indian housemaid.

The Leighs’ kitten disappeared on a Thursday, after failing to respond to her dinner bell. The next day, family and friends searched high and low for the cat throughout the neighborhood. They checked every stray cat and looked in every hiding place from where they had ever heard a cat yowl.

With all hope of finding the cat on their own, Charles placed the ad on Saturday. (He may have gotten the idea to place an idea by reading an old story about Snooperkatz, a shop cat whose owner had offered a $1 reward for the cat’s safe return.)

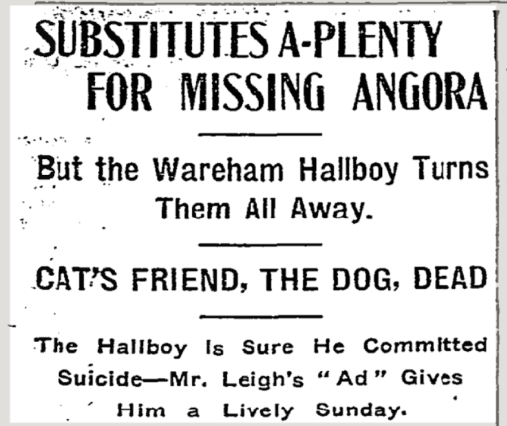

The first of the many gold diggers seeking $500 arrived at the apartment house carrying a cat in a bag. The New York Sun described it this way: “It was a long haired cat that looked as if it had seen better days and many of them. It was about as far from kittenhood as it could get and be alive.”

“That ain’t our cat,” the Warham’s janitor told the young reward seeker. “That’s just a common everyday tramp cat. Ours was a regular diamond turtle-back Angora goat cat.”

The dejected boy let the cat out of the bag and walked away without any reward money.

Two older woman, described by the New York Sun as “spinsters,” tried to pawn off two long-haired cats as the missing Angora. The janitor told them that the Leigh kitten was not twins, so they would have to take their cats away. The women commented that any man who could pay $500 for a kitten could pay $100 “for the fine specimens they had.”

Many more people tried to claim the reward throughout the day, creating a “cat line” down Lexington Avenue. As one newspaper noted, everyone simply left their dejected cats in front of the Wareham, “and the Sunday night concert in the neighborhood was unusually strong.”

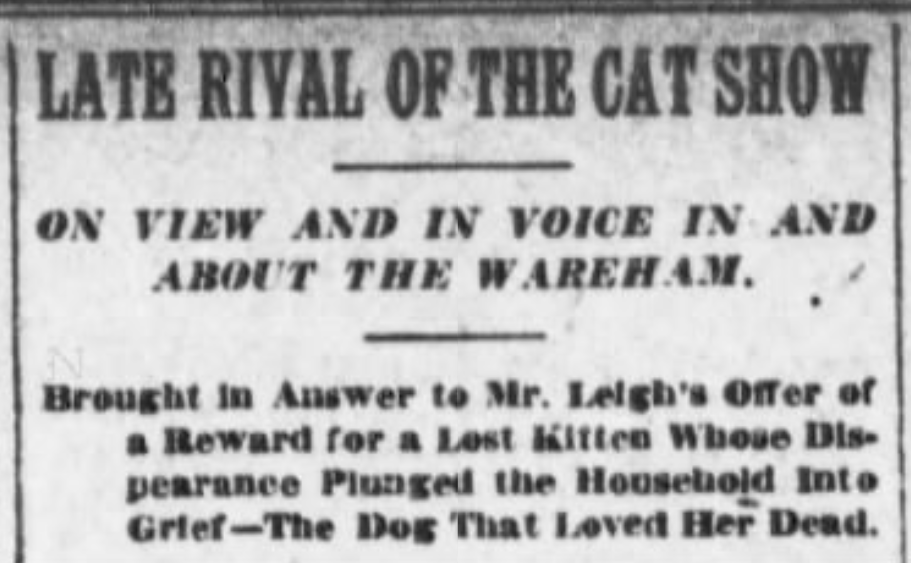

While everyone’s attention was focused on finding the missing kitten, poor Jimmy moped about the apartment in dismay over losing his feline friend. He was so distraught, he wouldn’t even touch his food.

On Sunday evening, Jimmy died in a bathtub in the apartment. The Wareham elevator men surmise that Charles had given the dog a bit too much medicine in the hope of reviving his spirits.

Ironically, if true, the druggist’s dog died of an overdose. The press did not report on the outcome of the missing Angora kitten.

Charles died only 9 years later, at the age of 49, on April 10, 1916. The cause of death was listed as a brain hemorrhage.

Apparently, Charles had eaten a large dinner the night before, and then returned to his shop at 158 Madison Avenue to review some paperwork. His associate and fellow chemist, Patrick A. Fox, found him dead at his desk when he opened the shop the following morning.

Funeral services for Charles Leigh were held at his residence at 122 East 34th Street. He was buried at the Pine Hill Cemetery in Middletown, New York.

Incidentally, one year later, Patrick was issued a restraining order to prevent him from using the Leigh name on his products.

According to a 1920 article in the Middletown Daily Herald, Patrick, who was now the company’s secretary, was the only other person who had access to all the company’s product formulas. After Charles died and Mollie had taken over the company, Patrick copied the formulas and used the “Leigh” label without the family’s permission.

Makes you wonder about Charles’ death…

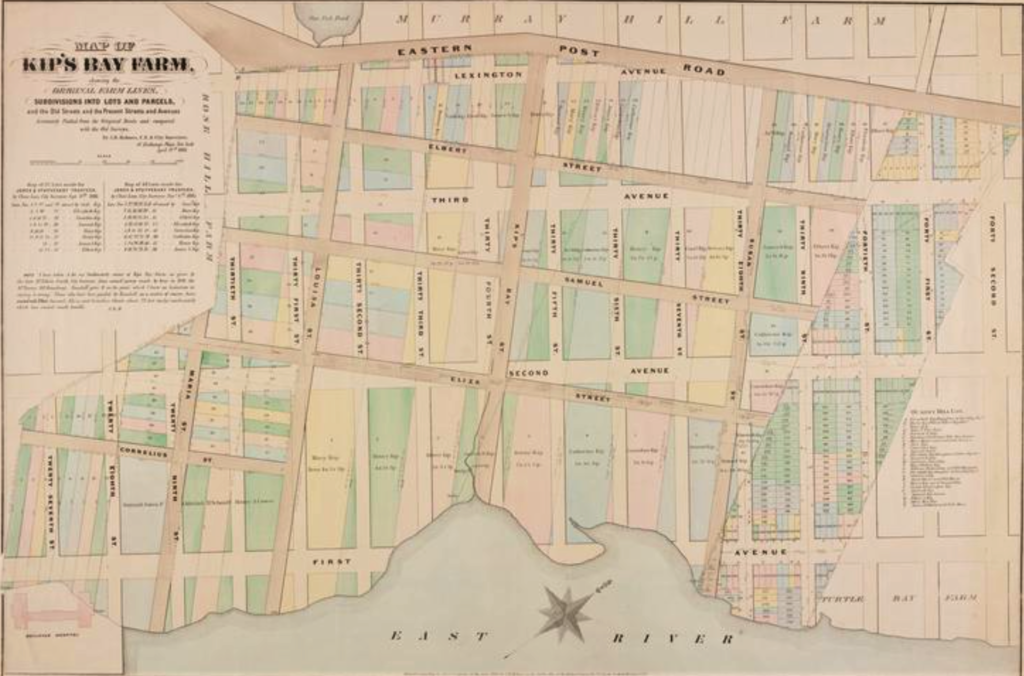

A Brief History of Kip’s Bay

The story of the Leigh family and their Angora kitten took place in the Wareham apartment building, which was constructed on the east side of Lexington Avenue at East 34th Street. This land was once part of the large Kip family farm, in what is now called Kips Bay (or Kip’s Bay).

John Randel map, 1818-1820.

The history of the Kip (aka Kuype, de Kype, Kipp) family in New York begins with Ruloff Ruloffzsen de Kuype, a French knight from Bretagne, France, who removed with his father into Holland in 1562.

In 1576, Ruloff’s son, Hendrick Rullofzen, was born. Hendrick married Margaret De Marneil, the the couple had three sons: Hendrick, Jacob, and Isaac. (It gets confusing because the family had a lot of boys with the same names.)

Hendrick and Margaret’s son Hendrick was born in 1600 in Nieuwenhuishoek (Netherlands). This third Hendrick married Tryntie (anglicized Catherine) Lubberts in 1624. The couple had six children: Cornelia, Isaac, Baertje, Jacobus, Hendrick, and Tryntje.

Sometime around 1637, the de Kype family came to New Amsterdam. Hendrick (the third) worked as a tailor and also served as one of the nine members of Governor Peter Stuyvesant’s Council.

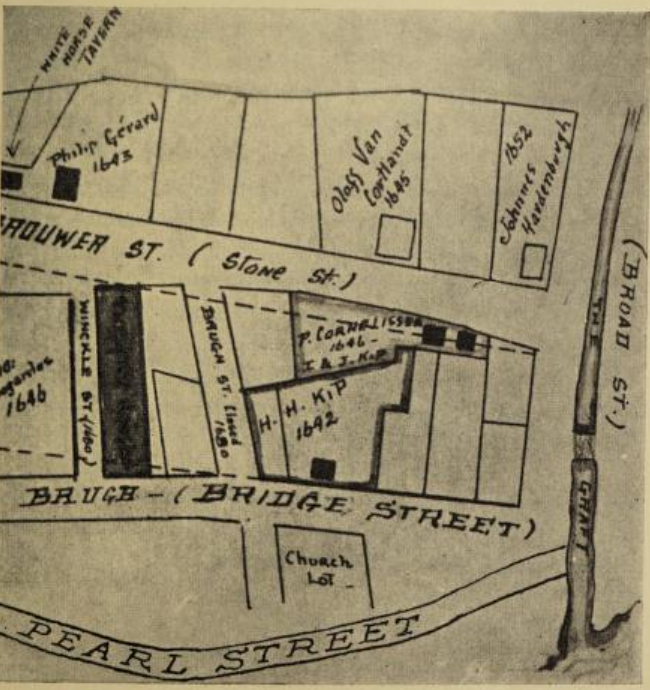

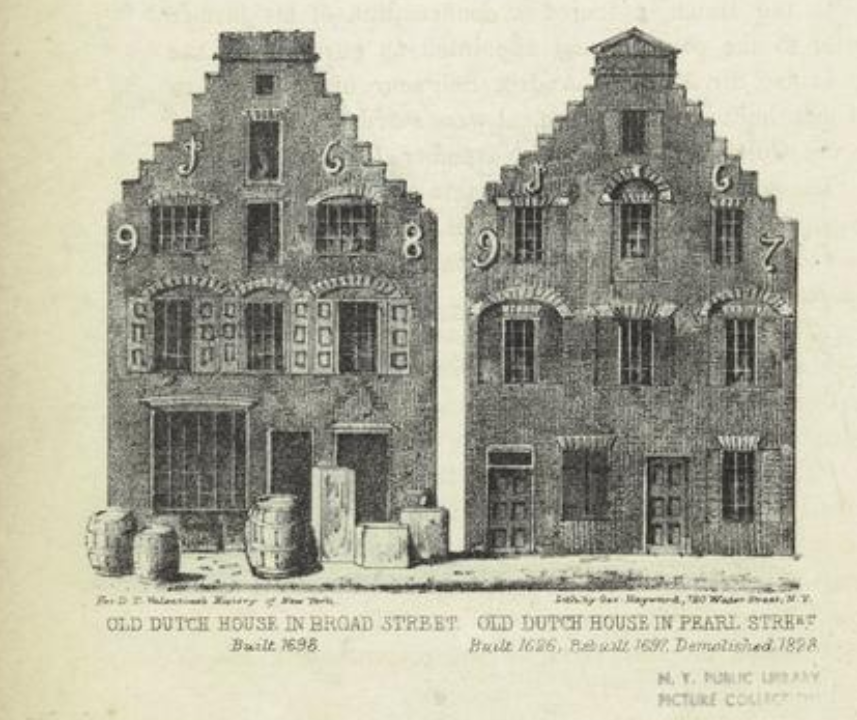

He established a home with a large garden on Bridge Street (at left). In later years, his sons Isaac and Jacobus (aka Jacob) would build their own homes on adjoining land on Stone Street.

Jacob Hendricks Kip was born in Amsterdam in 1631, just four years before the family came to America. As a teenager, he worked as a clerk in the New Amsterdam Provincial Secretary’s office; in 1653 he became the first secretary to the Court of Burgomasters and Schepens of New Amsterdam.

Jacob married Maria De La Montagne on March 8, 1654. They lived in the Stone Street house until 1660, when Jacob purchased a larger residence on Broad Street. The couple had 11 children over the next 27 years. (You guessed it, one of his sons was named Hendrick.)

In addition to their city home, Jacob and Maria established a summer estate along the road to Kingsbridge and East River a year after their marriage. The 150-acre estate, which Jacob called Kipsberry (it was also known as Kip’s Farm and Kipsborough), abutted the Murray Hill estate of Robert Murray to the west and the Beekman estate to the north (about present-day 26th to 44th Streets).

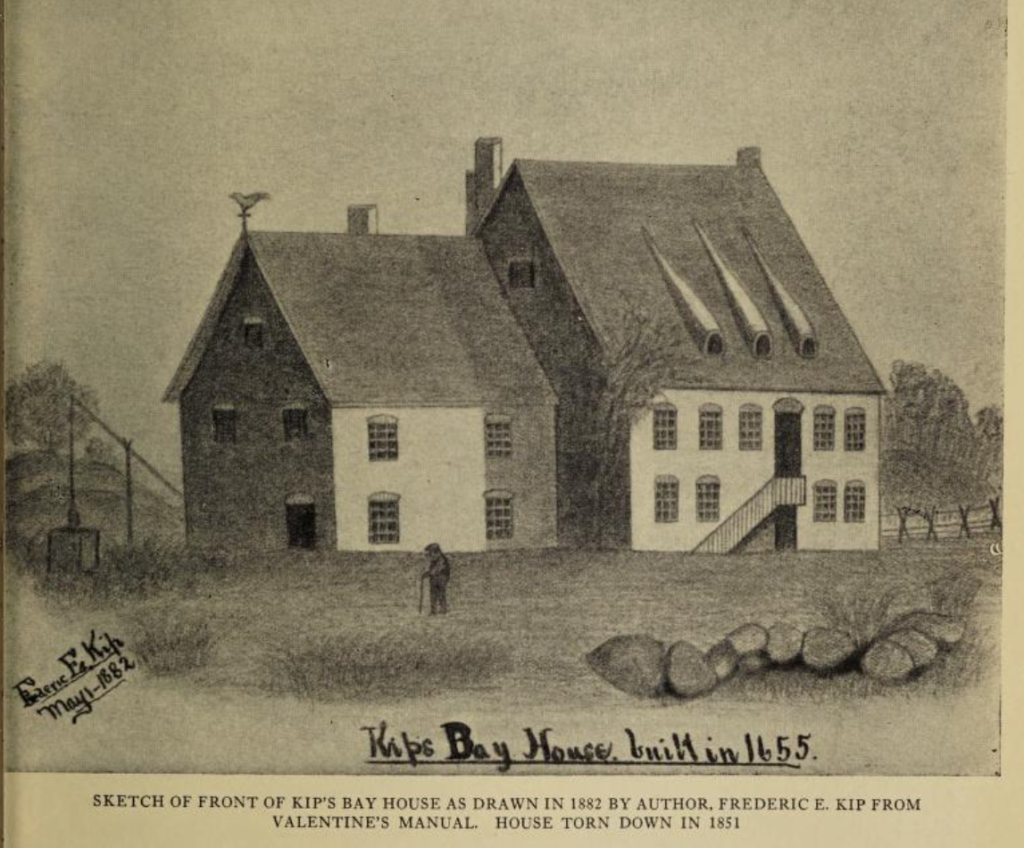

By 1655, Jacob had completed a mansion house on the property at what is now Second Avenue and 35th Street. It faced the bay on the East River, called Kip’s Bay. The farm became famous for its plum, peach, pear, and apple trees, as well as its fine rose gardens.

According to Frederick Ellsworth Kip, the Kip mansion was “a double house built of small yellow bricks imported from Holland, with a wing almost as large as the main building, and a steep peaked roof surmounted by a weathercock. Over the door was the Kip arms sculptured in stone, and on the gable the date of its erection.” Parts of the house were rebuilt in 1696.

Over the years, the Kips Bay house passed to Solomon (aka Samuel) Kip and then to his son, Jacobus, born in 1706. Jacobus was in his 70s during the Revolutionary War and too feeble to take up arms. So when the British used the house as their headquarters during the Battle of Kips Bay, he and his wife Catharina and their daughters took refuge in the cellar.

The next owner was another Samuel Kip, born at Kips Bay in 1731. Samuel was the one occupying the house when George Washington paid the family a visit following the war.

The Kips would continue to occupy the old house until 1851. That year, the city planned the extension of 35th Street, which prior to this time was a winding lane leading from the home to the river. To accommodate this progress, the city tore down what was then the oldest house in the city.

From 1878 to 1942, the Second Avenue elevated train ran over the site of the old house. Today, the el train is gone, but 35th Street still runs over the actual spot where the mansion stood. The Wareham apartment building still stands in all its red brick glory.