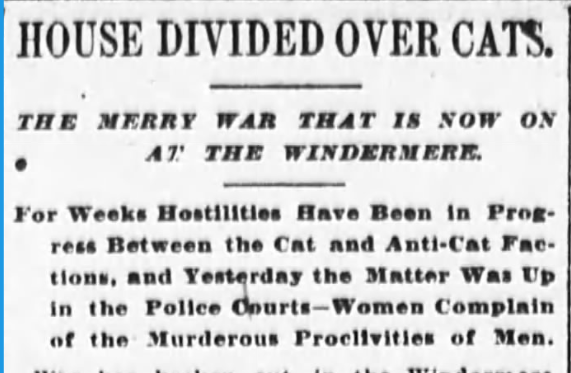

In the spring of 1899, 18 years after the Windermere opened at 400 West 57th Street, a war broke out between the cat-loving and cat-hating tenants. The war began when someone shot and killed about 13 pet cats. That someone was allegedly Charles Beard, the Windermere’s resident carpenter and a member of the building’s Anti-Cat Club.

I must warn you that this true story involves gun violence against cats, but it also provides a unique insight into life at the Windermere (one of the city’s oldest apartment buildings) and life in Old New York. Before I tell the story, a little history about the Windermere–one of New York City’s oldest known apartment buildings–is warranted to set the stage.

A Brief History of the Windermere

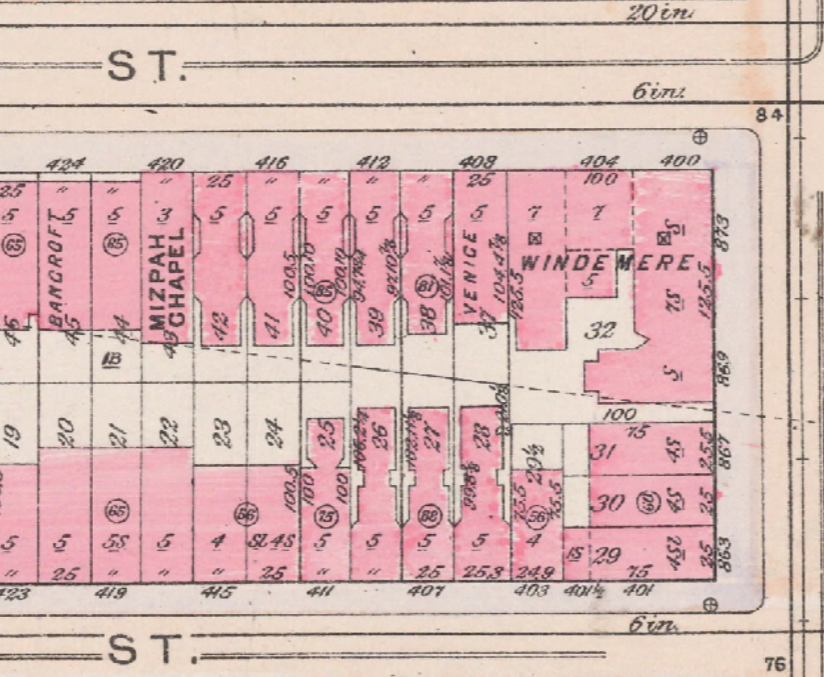

The story of the Windermere begins in 1879, when a young clerk, a builder, and a lawyer joined forces to purchase a plot of land on the southwest corner of 57th Street and Ninth Avenue. The land had once been part of the 200-acre Cornelius Cosine farm at Bloomingdale, which spanned from present-day 53rd to 57th Streets between the North River (Hudson) and the “common lands” near Sixth Avenue.

The men–William E. Stewart, William F. Burroughs, and Nathaniel A. McBride–hired architect Theophilus G. Smith to construct a luxury apartment building featuring 39 apartments of seven to nine rooms each. The seven-story, three-winged building had state-of-the-art features such as hydraulic elevators, telephone service, communal kitchens in the basement (for those who did not wish to cook in their own apartment), electric fire indicators, marble fireplaces, parquet floors, mirrored parlor walls, dumbwaiters, and steam heat. There were also hall boys on duty day and night and a private passageway on Ninth Avenue for use by bakers’ and grocers’ wagons.

The going rent was $600 to $1,100 — a year.

The building first attracted wealthy families, but as newer and nicer apartments such as the Dakota and the Osborne opened, the Windemere began emptying out. Around 1884, under the ownership of James R. Keene (who purchased the building in 1882), a newly divorced teacher and school principal named Henry Sterling Goodale (1836-1906) took over as the building superintendent and made some dramatic changes.

Goodale, who had three daughters and a son with his former wife, Dora Hill Read, came up with the idea to market the apartments to single and financially independent women who did not wish to live with their parents. The New York Times referred to these women as “the new woman,” and noted that thirty years earlier, these women “with a latch key and no chaperone” would have been called “a poor little old maid.”

Two of his daughters, Elaine and Dora, were independent poets, so he was familiar with how difficult it was for single women to find acceptable living arrangements other than in the old and dangerous boarding and lodging houses. When women began asking him for just one or two rooms, he agreed to making arrangements to accommodate their needs.

Under Goodale’s plan, the women–many of whom were described as “Bohemian” artists, painters, actresses, and writers–rented one to three rooms within each original apartment. In that way, Goodale did not have to spend a fortune reconfiguring the building.

The tenants of each flat lived independently of one another, but they shared the kitchen at the end of the hall and the one bathroom (a few woman had their own small suite with a small gas stove). A former eight-room apartment could accommodate five women, for example, or seven women could share a former ten-room apartment. As the New York Times noted, it was sort of an experiment to see if so many women could live under one room in peace. (Maybe not.)

One lucky female artist shared a three-room studio with her mother on the top floor; they even had a skylight. There was also a duplex on the top floor with a tiny kitchen and stairs that led to a small room built on the roof. One well-known literary woman had her own separate “house” on the roof where she lived on her own for some time.

The grandest of apartments in the Windermere was Goodale’s suite of about three small rooms on the top floor. In addition to these rooms, several steep, carpeted stairs led to a one-room study that Goodale built by himself on the roof using second-hand materials. Goodale called this study “Sky Parlor,” in honor of his family’s farm in Massachusetts, Sky Farm.

The study had windows on all sides, and held two tables, a couch, and several chairs. There was also a small alcove featuring stained glass windows and a pair of andirons with a gas log that Goodale could use when the steam heat was not enough to keep him warm. (This was perhaps not such a great idea.)

Just outside the windows of this little roof conservatory was a henhouse and a garden with evergreens and pink morning glories. From the roof, one could see the Statue of Liberty and Hudson River, and as far as the Long Island and New Jersey shores.

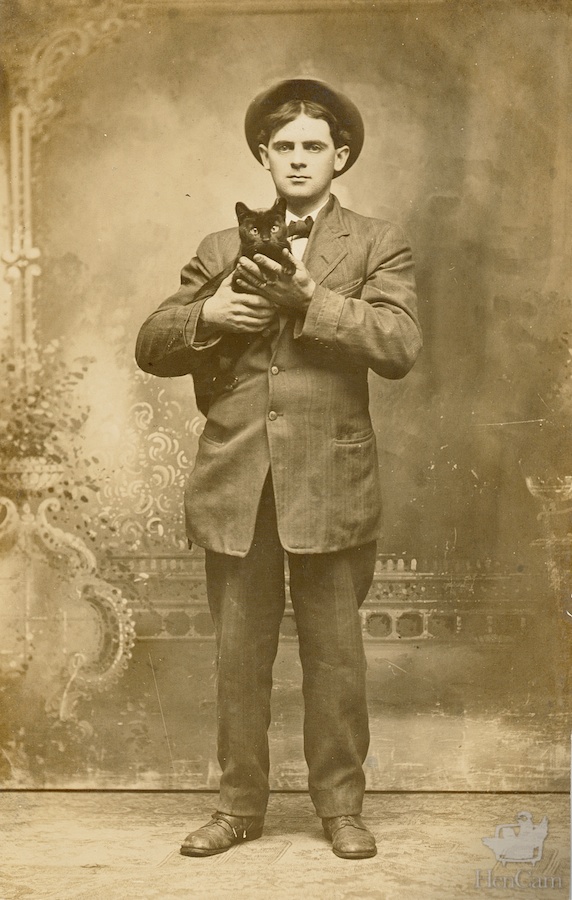

Not only did Goodale keep chickens and pigeons on the roof, but he also allowed the residents to own cats and dogs and birds. By the late 1890s, about 80% of the building’s 200 residents were women, many of whom loved and owned cats.

Unfortunately, a few dog owners who disliked cats also lived in the building, including a few male tenants who made up the minority of the population. One of the female residents who owned a trouble-making Willoughby pug named Puggy also had an aversion to cats.

The Fight Begins

One of the features of the Windermere was a large, 30-foot-square inner courtyard for the residents and their pets. Puggy would amuse himself by chasing the cats around the court, despite multiple protests from the cats’ owners.

When his owner refused to remove Puggy from the courtyard, the cat owners sought revenge by introducing “a large, well-trained, meat-fed cat from a neighboring butcher shop” into the volatile mix. The New York Sun gives a vivid account in May 1899:

When Puggy saw the new arrival he undertook to give it a little exercise. Exercise was what the meat-fed cat was there for. It met Puggy with a few well-chosen swings, jabs and uppercuts, and the rest of the performance consisted in his tearing around the courtyard uttering horrid shrieks, while the cat leisurely removed the cuticle from his back in parallel streaks.

When the show was over, and his mourning mistress had got Puggy away, he looked like a rag doll that had been struck by lightening. Thereafter the cats had it all their own way, and used to come out nights and sing paeans of victory on the field of battle.”

From that point on, the cats ruled the courtyard, and no dog dared intrude on their territory. For weeks on end, the felines held nightly concerts. Despite protests from several male tenants, the residents consented to suffer in (the lack of) silence and do nothing to stop the courtyard concertos.

According to the New York Press, pet cats with names such as Mousie, Sweetheart, Angeline, and Toddlekins “lifted up their voices in song often, alas, too often. Modesty might have saved them. But, no. Nothing but ‘Casta Diva,’ with trills, roulades, a toccata, sforzato and never a trace of decent pianissimo in the lot.”

In response to the courtyard jam sessions, one first-floor tenant began cursing out his window every night. This greatly offended a woman whom a reporter referred to as a “literary lady,” and she chastised him one morning at the communal breakfast table. The man darkly hinted at killing the cats, which caused two other women to take the literary lady’s side. A few men took the cursing man’s side.

The next morning, residents found a dead tabby in the courtyard. In his stiff paws was a card that said, “Riddle: Why is a Cat Like a Swan?” The inference–that this was the feline’s swan song–was not missed on anyone.

The cat-loving women formed a committee to keep watch of the men who wanted to harm the nocturnal singers. They poked holes in their window shades and spent hours at night peering into the courtyard with hopes of catching the cat killer in action. A few days later, however, a dead brindle tabby cat was discovered in the courtyard next to a broken pitcher.

At the breakfast table, a newspaper artist who lived on the third floor admitted the pitcher was his, but he claimed he had left it on a window ledge filled with milk. He said the cat must have gotten her head stuck in the pitcher and fell out the window. He then asked the owner of the dead cat to reimburse him 18 cents for the broken pitcher.

When the cat’s owner refused to reimburse the artist for his pitcher, he announced he was forming an Anti-Cat Club. Two lawyers, a bicycle agent, and an accountant swore allegiance to the club. The women swore at the men.

Things got nasty from this point on. Some of the men began bragging about striking the cats and lofting them over the roof with their golf clubs.

Someone hung a cloth cat stuffed with sawdust outside one of the women’s windows, which sent her into a full-blown panic when she peered from her peep hole that night. (The cloth cat had a placard that read, “Presented for autopsy by the Anti-Cat Club.”)

Another night, someone tossed firecrackers into the courtyard, sending all the cats scurrying for cover with their tails between their legs.

Over the next few days, 13 cats–with names like Margherita, Arline, and Santo Espiritu–were found dead by gunshot in the courtyard.

Then one day someone made the mistake of taking a shot at Black Paul, a large cat owned by Gus Johnson, the building’s elevator boy. One of the woman heard the crack of the rifle and was able to track the weapon to the basement. The Windermere’s carpenter was hanging a Flobert rifle on the wall when the cat-loving detective squad walked in on him.

Charles Beard told the women that while he was not, in fact, a member of the Anti-Cat Club, he now had every intention of joining it. The women summoned the police and Agent Evans of the Bergh Society (Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals), who charged Charles and sent him to the West 54th Street Police Court.

Unfortunately, the elevator boy refused to press charges, as Black Paul was beginning to recover from his injuries. The women had no proof that Charles had shot and killed the other cats, and so the magistrate had no other choice but to dismiss the charges.

Due to his injuries, Black Paul was no longer able to swell up his tail when confronted by other cats. The women said he would probably die of a broken heart, and that when his end came, they would “bury him with full honors and an inscription declaring him the victim of a murder plot of the Anti-Cat Club.”

The Hammock Races

When the residents weren’t fighting over cats, they were fighting over hammocks on the roof.

According to the press, men and women often gathered on the roof to watch the sun set over the Palisades and smoke cigars. The members of the “Roof Club” would hang hammocks on the roof during the summer months, only to find them taken by others when it was time to retire for the evening.

After-dinner scrambles to the roof to claim the hammocks were quite common (I imagine these were similar to the way cruise ship passengers rush to the pool deck every morning to snag a coveted lounge chair by the pool).

Goodale wrote a poem about the hammock races:

A hammock swings light in the breeze of the night

‘Tis yours, Judge, you ought to be in it;

But alas! Yes, the loveliest Windermere lass

Lies a-dream in its meshes this minute.

The Windermere Fires

Cats and hammocks may have led to residential scuffles, but a series of fires in the building may have very well led to the Windermere’s decline and demise.

Even before the Windermere was completed, a fire in what was then Austin P. Gibbins’ five-story apartment building at 402 West 57th Street spread to the unfinished Windermere in the early-morning hours of February 6, 1881. With the flames growing in intensity and spreading through the Windermere’s unfinished doors and windows, the firemen were forced to focus on the existing building and let the Windermere burn.

The fire’s glow lit up the west-side neighborhoods, from 42nd to 72nd Streets. The rear wall of the Windermere fell down during the fire, and police deemed the front wall unsafe. Party walls saved the entire building from destruction, but McBride and Smith reportedly lost $30,000 and had to basically start over again.

An early-morning fire of mysterious origin in 1893 sent residents scurrying to the streets with their pets and night robes and Mackintosh jackets. The fire caused little damage, but the press had a field day detailing the fleeing residents’ “scarcity of wearing apparel.”

In 1896 and 1897, several fires took place, including one on April 19, 1897, which caused more excitement than damage. The fire originated in a common bathroom on the second floor, perhaps from an overheated steam pipe. Goodale was able to keep the flames in check using a pail of water while Thomas Wright, the night watchman, warned the occupants.

One woman who lived on the top floor ran into the hallway barefooted and in her nightgown, screaming at the top of her lungs. Another woman ran from her apartment on the sixth floor with a parrot under her arm. The woman shouted, “Fire!” The parrot shouted, “Shut up!” The parrot’s command silenced everyone’s screams.

Two years later, in July 1899, another fire created much drama at the Windermere. This fire started in Goodale’s rooftop study (probably caused by the gas log).

According to the New York Press, an engineer on the Ninth Avenue elevated railroad saw the flames first, and sounded an alarm by tooting the whistle of his engine. A patrolman who heard the whistle sounded the fire alarm and rang the electric bells in the building to awaken the residents.

As the Windermere residents began running through the halls and pounding on doors, Charles Beard (the alleged cat killer) took command of the elevator and made about 20 trips to get all the tenants safely to the street.

Although the fire never reached the main building, it did destroy Goodale’s apartment. The hens and roosters on the roof also died in the blaze.

Shortly after this fire, the Windermere was overhauled and its name was changed for a few years to the Winchester. Goodale also left his position about this time (perhaps because his apartment burned down.)

The Windermere made the news again in February 1907 when a fire started in a trunk room in the basement. Abraham Quinn, who worked in a decorator’s store in the basement, alerted elevator boy Edward Merley (aka Scrappy) of the blaze, who sent someone to sound an alarm while he and Quinn attempted to put out the fire with a hand fire extinguisher.

The fire spread into an elevator shaft, where it burned from the third floor to the roof. Merley ran the elevator up to the third floor to rescue several residents, including Mrs. Dorothy Dean and her maid, Laura Kinson. Also rescued were Dorothy’s dog, Dan, her gray cat, Bum, and her unnamed fur coat. Reverend Clinton Eddy, a male cat lover, carried out his two cats in a bag.

Due to deep snow and frozen hydrants, the firemen were delayed in extinguishing the blaze. The fire caused extensive damage to the sixth and seventh floors; a young man found carrying a hammer in the building was arrested and charged with arson.

As for the pets, Dan the dog escaped and was not seen again. The cats survived.

The Fall of the Windermere

In the 1970s, as the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood headed into a downward spiral, the Windermere was reduced to low-income housing with more than 160 single-room-occupancy (SRO) units (in other words, single rooms with shared kitchens and bathrooms). These rooms were often a magnet for drug dealers and prostitutes.

In the 1980s, owner Alan B. Weissman began trying to evict tenants by way of extreme harassment. Residents charged the managers with ransacking their rooms, blocking doors shut with cement, and even issuing death threats.

Building manager Jerome Garland was arrested and sent to jail for threatening to kill tenants if they didn’t vacate. Weissman was also jailed for mistreatment.

In 1986, a Japanese company, Toa, bought the Windemere. The building sat empty for years until it was designated a Landmark by the Landmarks Preservation Commission on June 28, 2005.

Toa never redeveloped the property; in 2008 the company was charged for willfully failing to maintain the building. The final tenants moved out in 2009 after the fire department deemed the building unsafe: city inspectors had issued 649 violations.

In 2009, developer Mark Tress acquired the Windermere for $13 million. Tress said he would turn the Windermere into a boutique hotel with 175 rooms and a rooftop restaurant (a second option was to convert the building into office space). The storefront on Ninth Avenue is currently undergoing renovations, but the final fate of the Windermere is still to be determined.