On September 23, 1962, Philharmonic Hall (now David Geffen Hall) opened with an inaugural concert featuring Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic. The concert hall was the first building of Lincoln Center to be completed as part of the Lincoln Square Renewal Project (1955-1969).

About 40 years earlier, this exact location on the Lincoln Center campus was the site of another type of concert: a canine concert of barks and howls from dogs of all breeds and sizes. The dogs were all guests of the Grisdale Hotel for Dogs at 132 West 65th Street. Today this is the address for the David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center.

The hotel was run by Thomas Grisdale, aka The Dean of Gotham, a prominent dog dealer and award-winning exhibitor who specialized in bulldogs.

Born in Temple Sowerby in northern England in about 1865, Grisdale moved to Cleveland in 1885 and began showing dogs in 1888. After moving to New York, he worked for about 25 years as a breeder and exhibitor for William H. Newman, president of the New York Central Railroad. He apparently did such a good job watching Newman’s dogs, that the man rewarded the young Grisdale with an all-expense trip to London.

In 1912, Grisdale broke out on his own to start Gotham Kennels at 540 West 42nd Street (now a parking lot). The kennels were described as “the oldest established bulldog kennel in America,” where Grisdale sold “aristocratic dogs for aristocratic people.”

Grisdale began his hotel for dogs at the Gotham Kennels sometime around 1915. In 1918, he leased a three-story and basement building at 132 West 65th Street from the owner, Janette Ida Luqueer Hurlbut. (Incidentally, it was in this same building that James H. Anderson founded the Amsterdam News on December 4, 1909.)

The hotel featured a reception room and lobby (decorated with paintings of dogs), as well as tiers of “rooms” made up daily by a maid. Canine guests with a day pass could retire to these rooms for afternoon naps and overnight guests would sleep in them at night.

During the day, when they weren’t playing or being walked, pups could relax in the lounging room or sun parlor.

At the Grisdale Hotel, there was also a beauty parlor of sorts for the lady dogs and a barber shop for the male dogs. A tea room where dainties were served in the afternoon, a hospital room for sick guests, and a dental hygiene room provided even the most pampered pooches with everything they could need during their stays.

According to Grisdale, the manicuring department was the busiest department in the hotel. The dental room, where a dog dentist cleaned the dogs’ teeth or pulled teeth as needed if the puppy had too many teeth, was also in demand. Grisdale explained, “In promising bull pups, as in children, the teeth are often too crowded, and it’s better to pull out one or two so as to make a good-looking mouth for shows.”

When it came to food at the dog hotel, Grisdale said, it was “nothing but the best.”

Grisdale told a reporter that many of the dogs, whose mothers would leave them for a few days to “motor down to Long Island or Newport,” received too many sweets at home. These dogs were placed on a diet of eggs beaten in milk until some pounds came off. Then they were given the finest meat chopped finely, the best vegetables, and the most delectable and nourishing biscuits.

In addition to playtime, the dogs were walked every day. The hotel even had its own cab service with a cab specially built with a long bench on each side that was “just high enough for a gentlemanly canine to sit at his ease and look interestedly out of a plate glass window.”

For all these services, canine guests paid $1 a day for room, board, and attendance (the charge was $2 if the dog required additional grooming). Some smaller dogs could stay at the hotel all week for only $3. As the New York Evening World reporter observed, it was the only hotel in New York City with prices not affected by Prohibition.

When he wasn’t working at his kennels or the hotel, Thomas and his wife Emma (nee Martin) kept busy judging or showing their champion bulldogs at the various dog shows in America, Canada, and England. Thomas died in May 1937 at the age of 73. Emma, who was about 26 years younger, continued living in the city and showing dogs. She passed in 1980.

A Brief History of West 65th Street and Lincoln Center

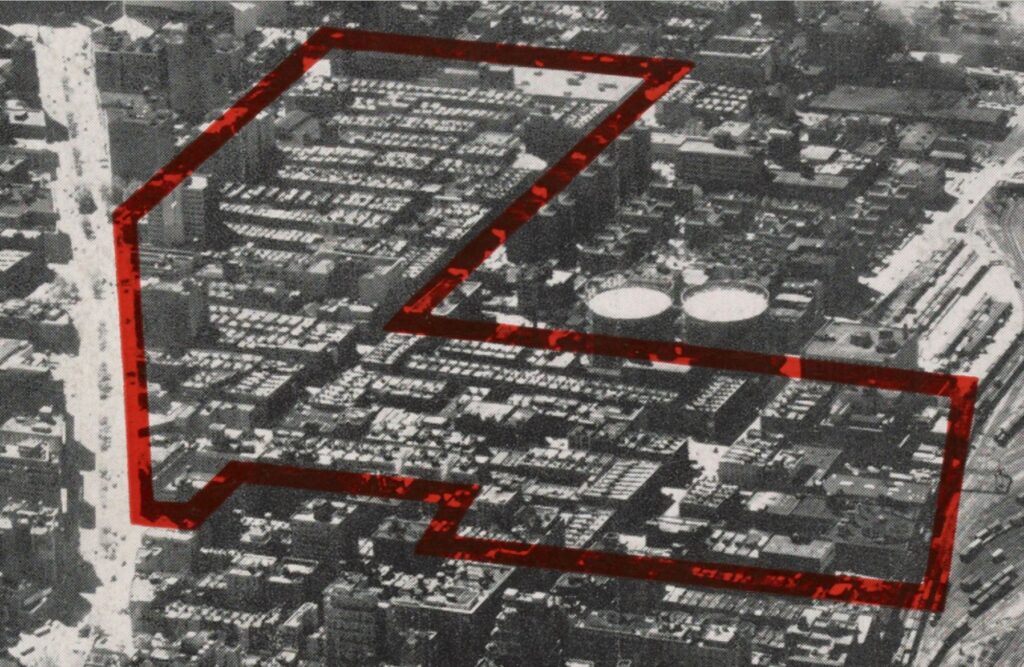

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts was the culmination of the Lincoln Square Renewal Project, which displaced more than 7,000 families and 800 businesses within 18 blocks of a neighborhood called Lincoln Square, aka, San Juan Hill. This neighborhood was bounded by Amsterdam and West End Avenues between 59th and 65th Streets.

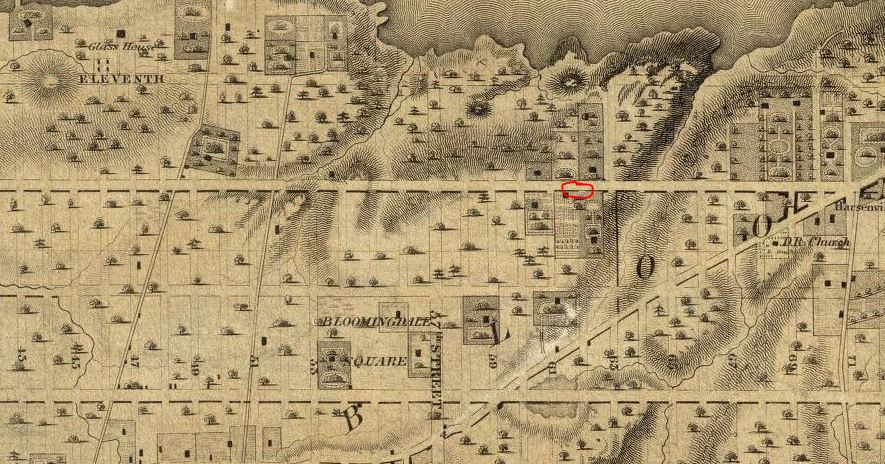

The recorded history of this part of New York City goes back to 1667, when Sir Richard Nicholls granted a patent for a vast amount of land on the west side of Manhattan to Johannes Van Brugh, Thomas Hall, John Vigne, Egbert Wouters, and Jacob Leanders. In the late 1700s, this area was known as Bloemendaal or Blooming Dale–the valley of flowers.

One hundred years later, in 1785, the Van Brugh land (318 acres) was conveyed to John Somerindike for $2,500 by the Commissioners of Forfeiture. From that point it was called the Somerindike (or Somarindyck) Farm. To the immediate north was the small hamlet of Harsenville.

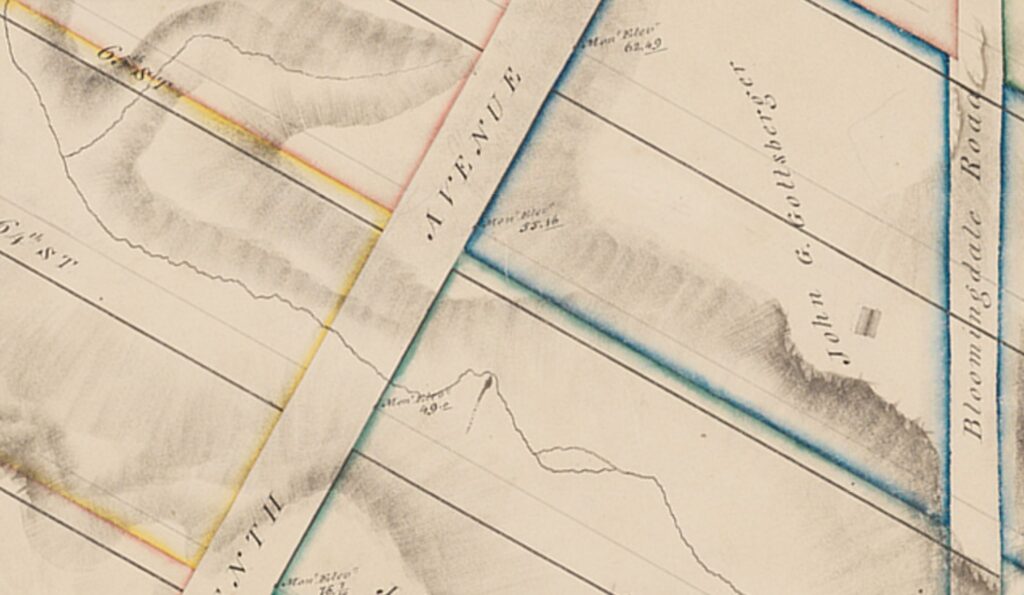

By 1817, the parcel of land where Lincoln Center now stands was owned by John George Gottsberger, an Austrian businessman who had arrived in America in 1811. In fact, the building that may have been Gottsberger’s country home (see below) would have literally been across the street from the Grisdale Hotel for dogs.

The last farm of record in this area was the John Low farm, bounded by 59th and 62nd Streets, the west side of Tenth Avenue, and the Hudson River. Due to its rocky topography, this area did not experience development until the mid-19th century.

Over the years, from the 1880s to the 1950s, the building at 132 West 65th Street was occupied by immigrants from many countries, including Germany, England, Switzerland, Turkey, Ireland, Russia, and the Philippines. The building was last occupied by one household with 12 boarders from Norway, Ireland, and Puerto Rico.

In 1940, the New York City Housing Authority called the San Juan Hill neighborhood “the worst slum section in the City of New York” and made plans to demolish all the old tenements. Nine years later, the Housing Act of 1949 was passed by President Truman under his Fair Deal. Title I, “Slum Clearance and Community Development and Redevelopment,” allowed local governments to take land considered to be slums under eminent domain and sell it to private investors to redevelop.

The act created a perfect opportunity for Robert Moses, who was able to frame San Juan Hill as a slum neighborhood in order to secure sponsors and approval for the Lincoln Center project. City officials called it “the greatest cultural development of our time.”

Fun Fact:

On May 24, 1962, a tuning test took place at Philharmonic Hall to test the acoustics and vibrations. The 2,612 auditorium seats were filled with ragdolls, some which were wired to see if there were any dead spots in the auditorium. A series of cannon shots were fired from the stage.

Prior to this test, before the buildings on West 65th Street were even demolished, vibration measurements were taken in the cellar of Harvey’s Bar at Broadway and West 65th. Those measurements were compared with similar measurements in the basement of the new hall. This test was conduced to see if subway rumblings would be heard in the hall. The results showed that the vibrations were less in the hall than they had been in the bar; the results showed that sounds of the subway would not be heard in the Philharmonic Hall.