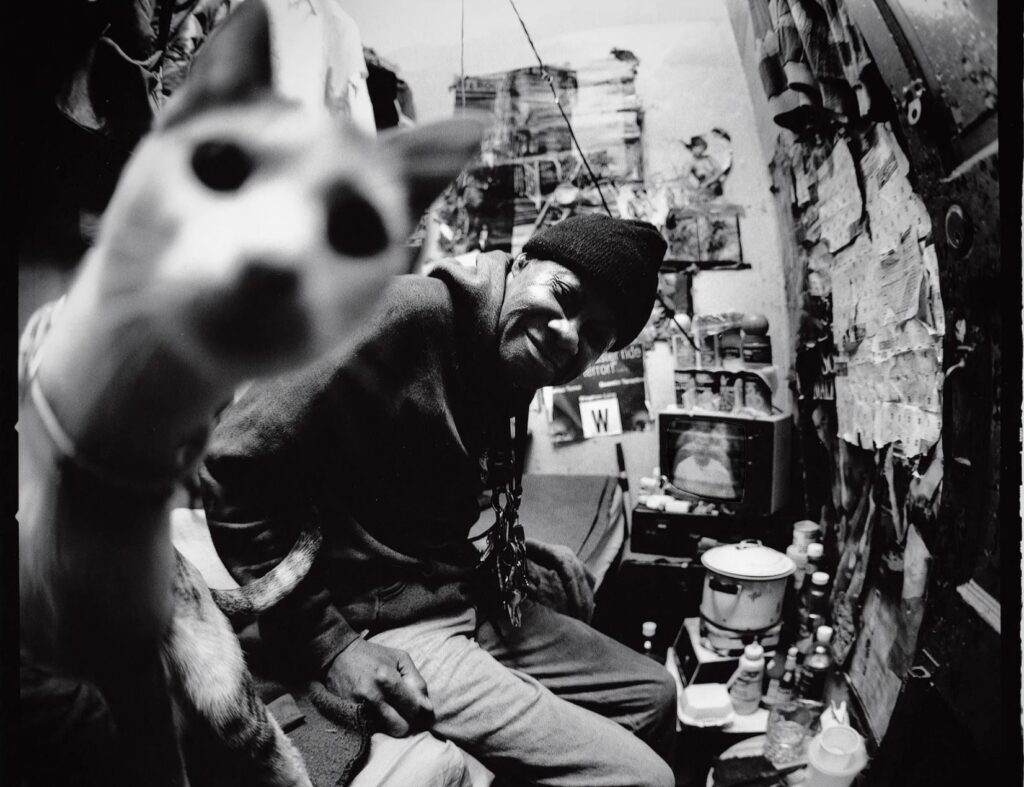

This photo of the Sunshine Hotel cat doing a photo bomb in the flophouse at 241 Bowery has stopping power. I can’t take my eyes off it. Can you blame me?

The photo was taken by Harvey Wang in 1998 and published in the book Flophouse: Life on the Bowery by David Isay and Stacey Abramson. In other words, this is not a cat of Old New York. But the building where this resident mouser made his home has an interesting history with ties to much larger animals: elephants and horses.

The Sunshine Hotel occupied the upper floors of 241, 243, and 245 Bowery, called Sunshine, Lakewood, and Annex, respectively. The lobby on the second floor of 241 Bowery was accessed via a steep set of narrow stairs; the three buildings were internally connected on the upper floors.

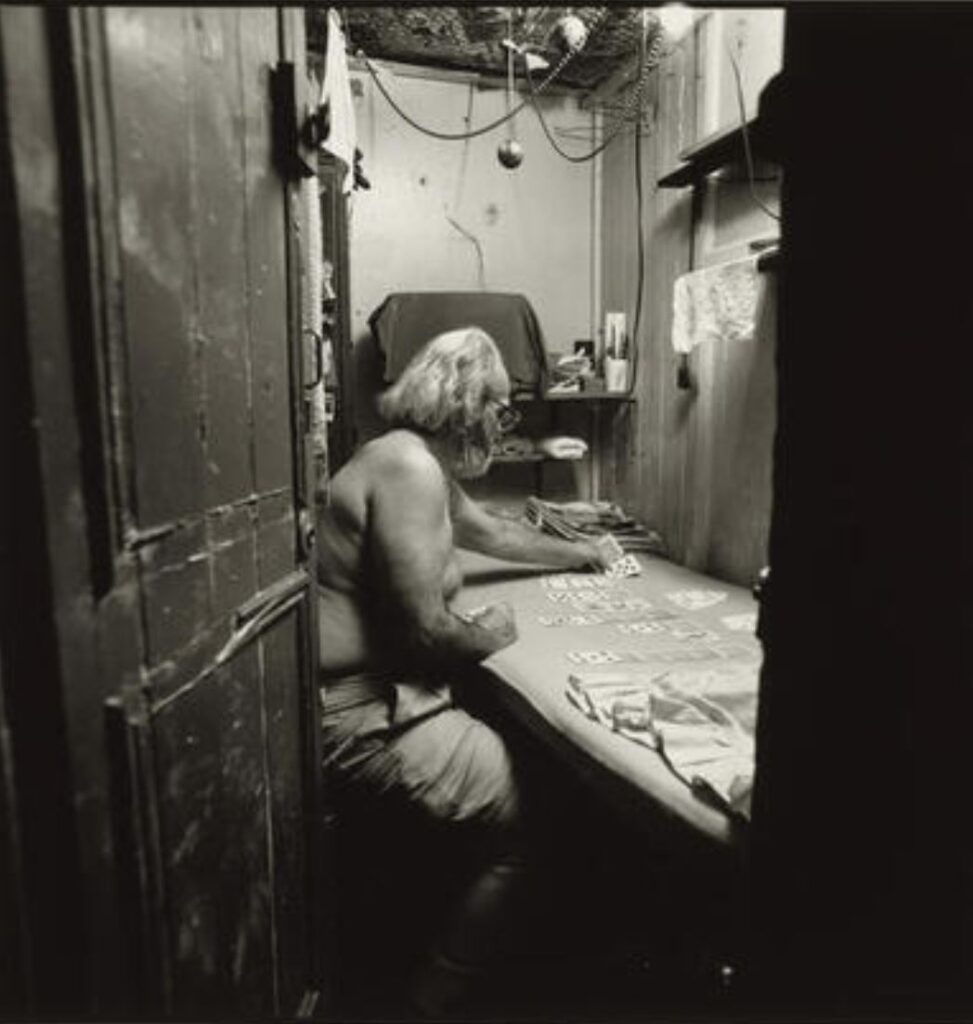

The hotel provided cheap housing in the form of tiny cubicles (4×6 feet) with chicken-wire ceilings and barracks-like dormitories. (The cubicles could not be considered actual rooms because they did not have real ceilings.) Talk about a fire trap.

When the hotel opened in the 1920s, guests could stay for 10 cents a night. By 1998, when the book was written and the photographer captured the cat doing a photo bomb, the rates were $8 to $10 a night.

Much has been written about the Sunshine Hotel. In addition to the book and numerous website articles, it was also featured in an award-winning documentary by Michael Dominic, which you can watch online or on Amazon Prime.

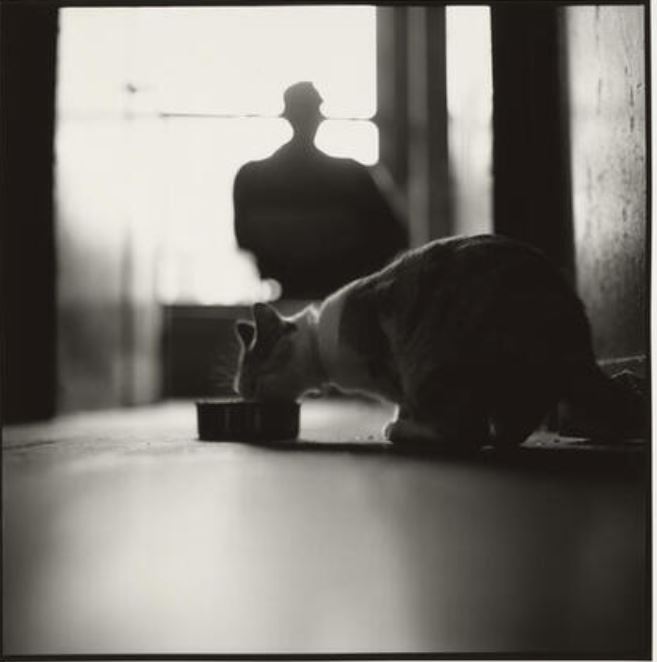

Nothing is known about the cat, but here is another picture of him in the flophouse:

The First Street Rail Road in America

As my website focuses on animals of Old New York, I’m going to tell you an interesting story about the history of 241 Bowery. There are no other cats involved from this point on.

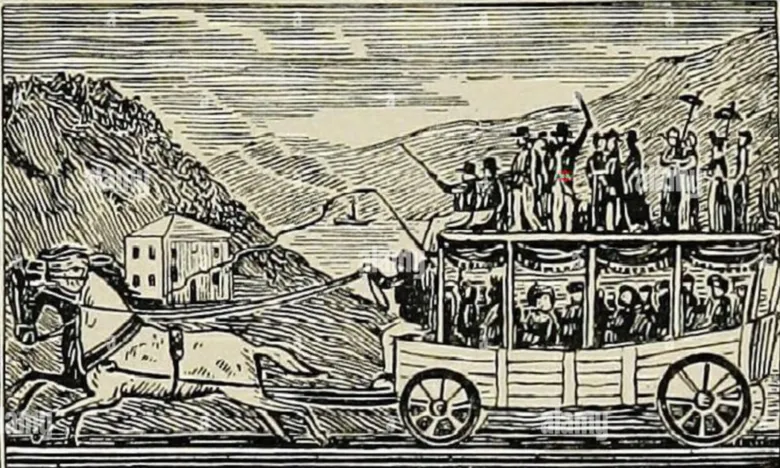

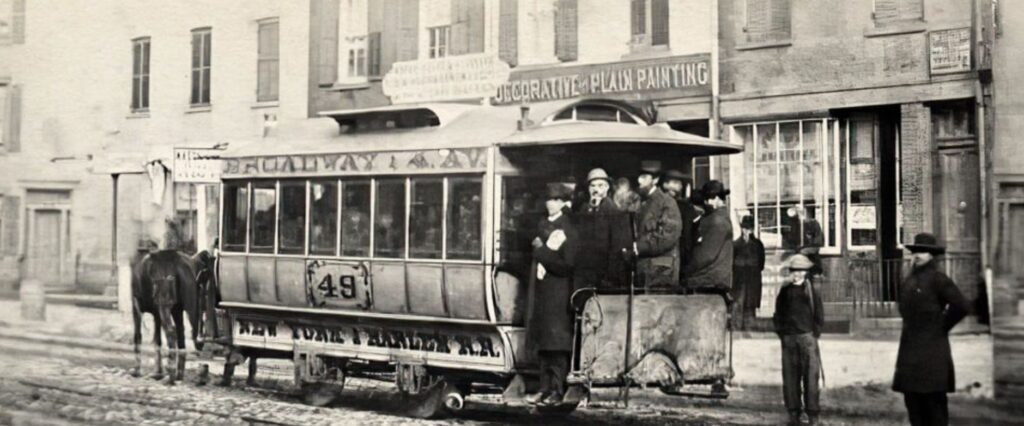

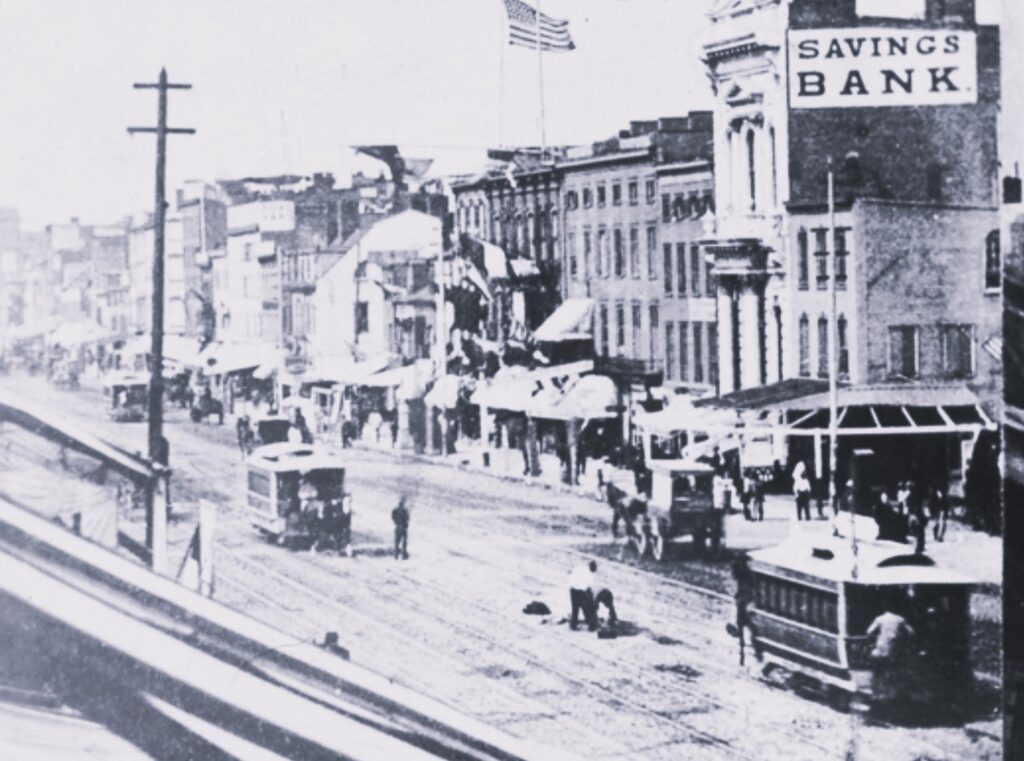

In 1832, the horse car was introduced to New Yorkers for the first time. The horse cars provided “rapid transit” of 10 to 12 miles an hour, which was much faster than the omnibus could go. The service was provided by the New York & Harlem Rail Road.

The New York & Harlem Rail Road was incorporated in 1831. A special act of the legislature allowed the company to build a street railroad from 23rd Street to the Harlem River. The company filed a map of the road along the center line of Fourth Avenue (now Park Avenue), and ground was broken on February 23, 1832. It would be the first street railroad to be built in the United States.

People were hesitant at first, because they didn’t want rails laid in the middle of the street. But the railroad company promoted the potential benefits, and promised that the street rail road would “make Harlem the suburbs of New York.”

The rail road, it was believed, would bring fuel and marble to Harlem for development, and there would be “cottages and villas with ample gardens and grounds belonging to city merchants where they can breathe the fresh air and have several acres for the price of a single lot of ground in the compact part of the city.”

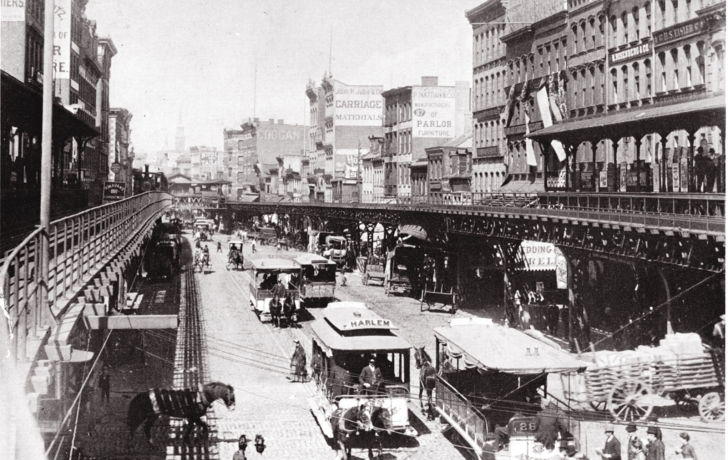

Recognizing that there was a need to help those living south of Prince Street who “wanted to venture to the unexplored country about 14th Street,” the company was granted permission to construct the road south of 23rd Street. The one caveat was that nothing but horse power could ever be used south of 14th Street.

The first experimental ride from Prince Street to 14th Street took place on November 14, 1832, on a car called the John Mason (named for the president of the rail road company). A week later, the company advertised the service: “The cars will run upon the rails from Prince Street to Fourteenth Street, in the Bowery…for the purpose of affording evidence to the public of the expediency of using rail-roads within the city.”

The horse-drawn street cars were a big hit with the public–who mostly used the service for pleasure or out of curiosity–albeit, they were quite noisy. According to one news report, the sound could be heard up to 3 blocks away from the Bowery, on account of the granite ties on which the rails were laid. (Two years later, the granite was replaced with ties made of Georgia pine; the granite was cut up and used as gutter stones.)

So what does this story have to do with 241 Bowery? It turns out, the ticket office for the New York & Harlem Rail Road was in “a prim little two-story building” at 241 Bowery. The office was on the ground floor, and John S. Whigham, the superintendent, lived upstairs.

The NY&HRR line was extended to 32nd Street in 1833, to Yorkville by 1834, and to the Harlem River (Harlem Bridge on 4th Avenue) in 1837. In 1839, the company moved out of 241 Bowery and into a larger ticket office on Wall Street.

In the 1840s, the rail road company expanded the line through the counties of Westchester, Putnam, Dutchess, Columbia, and Rensselaer to the City of Albany. The first passenger train from New York to Albany took place on January 19, 1853. The New York and Harlem Railroad eventually became the New York Central Railroad and then the Metro North Harlem line service that we have today.

Incidentally, it was the construction of the Third Avenue elevated line in 1878 that coincided with the next era of 241 Bowery. Once the El train was in operation, most middle-class New Yorkers stayed away from the Bowery, and the neighborhood took a downward turn toward cheap entertainment in the form of dime museums, brothels, and saloons.

That year, a man by the name of Frank Hughes opened a sleazy saloon and brothel at 241 Bowery called the Sultan Divan. The male-oriented saloon advertised its beautiful barmaids and featured a Grand Barmaid’s Show every evening. The saloon also advertised that people could “see the elephant” at the Sultan Divan; whether this was an actual elephant or not, I cannot tell, but I have a feeling it was real.

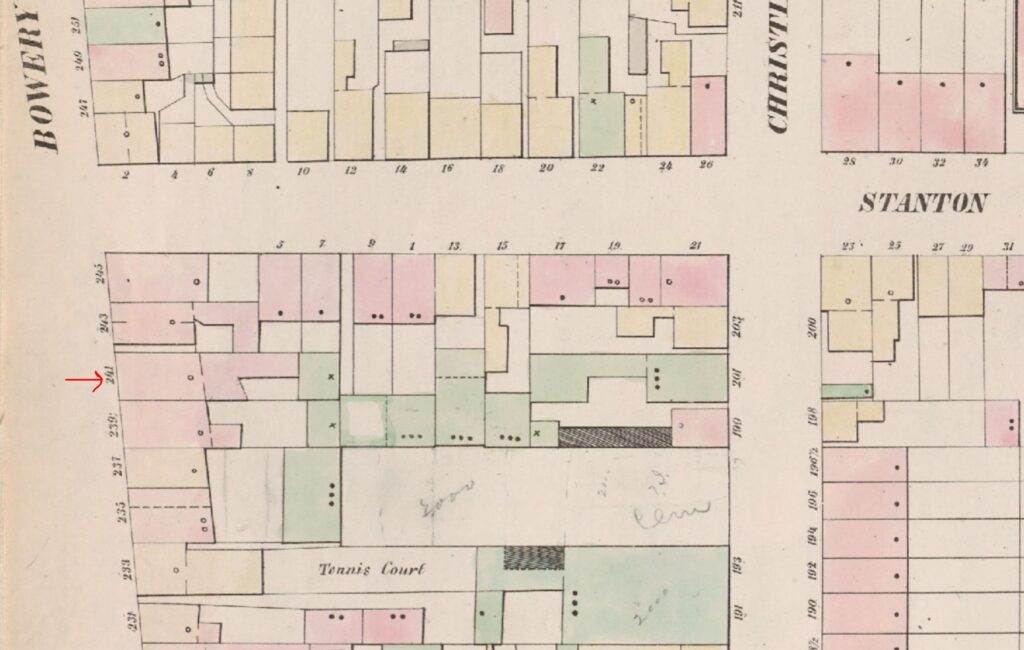

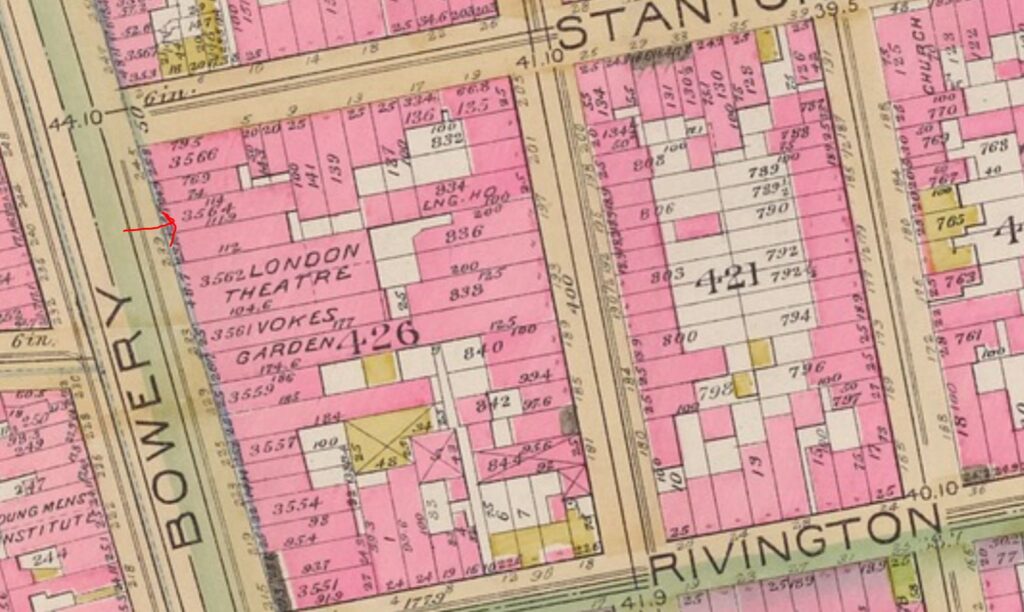

As an aside, note the tennis court at the bottom of this 1853 map above. I just had to find out what this was, and by typing in “233 Bowery” in the newspaper archives, I learned quite a lot.

The court behind the frame building at 233 Bowery was actually a “bat ball alley” owned by a man named H. Woolly. Woolly opened the court in 1846, advertising that “a four-handed match of ball for One Hundred Dollars” would be played there (the game was supposedly a cross between cricket and squash).

The “tennis court” was a 120-foot alley with a gallery for spectators, and Woolly would serve liquor and cigars to the patrons. In the 1850s, a large building on this site was called The Bowery Racket (sic) Court, which was actually a bowling saloon operated by Harmon C. Swift. In the 1860s, a professional cricket player named Harry Wright opened a cricket batting cage on the site.

The former tennis court was next the site of the Volks Garten Music Hall, managed by George J. Kraus until 1893. The building was then occupied by Conkling’s Museum of the Late War, but the museum didn’t last long. A few days after it opened, on November 23, 1895, a gas company meter inspector named James Hagan tried to read a meter with the help of a lit candle while investigating a gas leak in the basement. Boom.

Getting back to 241 Bowery:

In 1883, a man by the name of Beefsteak John (John Rudolph Haefler or Hoeffler) established an eating place in the now three-story brick building at 241 Bowery (his former eatery, which he established around 1869, was located in a basement on the corner of Houston Street and the Bowery). John’s sister Gertrude and her husband, Thomas Ehler, lived on the floor above, and John and his family lived on third floor. Several servants lived on a top floor, which was more like an attic.

Beefsteak John, who founded the city’s Beefsteak Club, kept a large drum stove in the center of a large room, and he served nothing but beefsteak and potatoes. Men would sit around the stove and drink beer with their steak and potatoes.

In October 1884, a fire broke out in a vat of hot fat (with pigs’ feet) in the adjacent one-story extension, which served as a kitchen. The fire spread and destroyed the rear of 241 Bowery, burning through the roof (perhaps this is why the building is only three stories today). The residents, especially the servants on the top floor, barely escaped with their lives via the roof, smoke-filled stairwells, fire ladders, and windows.

In later years, 241 Bowery would be occupied by a gambling house and saloon operated by Dennis “Dinny” J. Sullivan (the police raided the saloon in 1900); another dive bar operated by James J. McDermott; and a “putrid dive” owned by a notorious gang leader named Frank “Chick” Tricker, who called his place the Flea Bag.

By the 1920s, the Bowery had more than 100 flophouses in a 16-block stretch. One of those flophouses was the Sunshine Hotel at 241 Bowery, which Frank Mazzara, a broom maker, opened in 1922.

In 2014, hotel owner Roseann Carone converted the second and third floors of 241 Bowery into commercial loft space (the 30 to 40 remaining hotel residents were relocated to the neighboring building at 239 Bowery). A Greek eatery is on the ground floor.