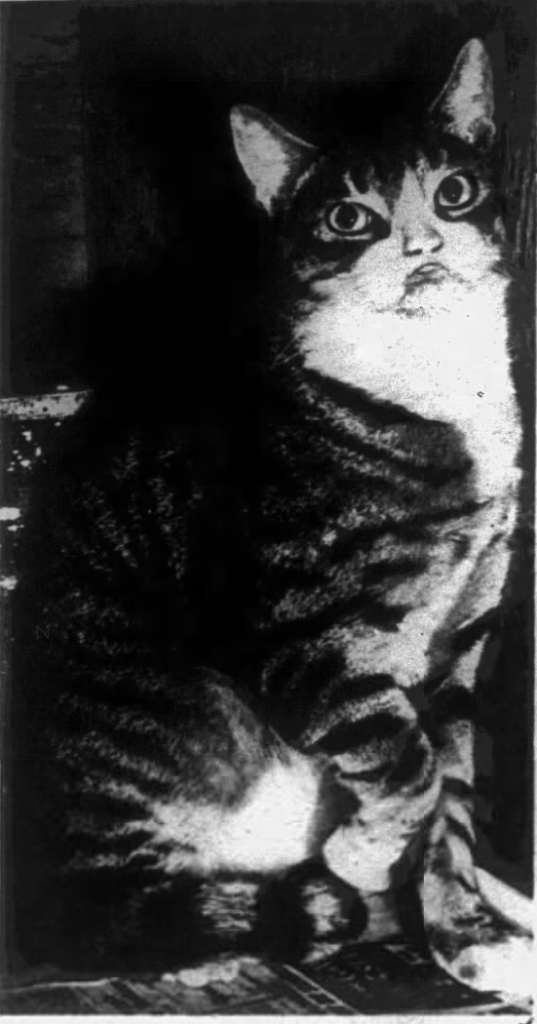

Tommy Tucker was just an ordinary (and perhaps ornery from the looks of this photo) tabby cat who lived in a large frame home at 1384 Riverside Drive in Washington Heights. His owner, Louise Baier, was an animal-loving woman who shared her home with Tommy and a widowed housekeeper named Katherine Schultz.

Although Ms. Baier was not employed, she did have a wealthy brother, Dr. Victor Baier, who was one time the choir master for Trinity Church. When he died in 1921, Louise inherited one half of his estate and all his jewelry and household items.

When Miss Baier died at the age of 75 on March 6, 1939, she left the bulk of her estate–estimated at about $300,000–to the ASPCA, the Ellin Prince Speyer Hospital for Animals, the New York Women’s League for Animals, and the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. She also bequeathed $15,000 to Miss Schultz and $5,000 to her four-year-old tomcat, Tommy.

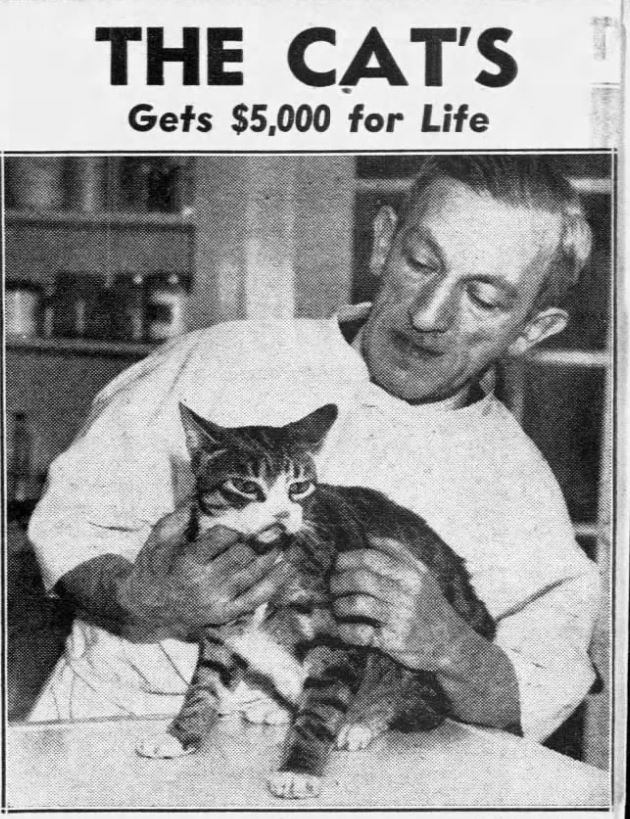

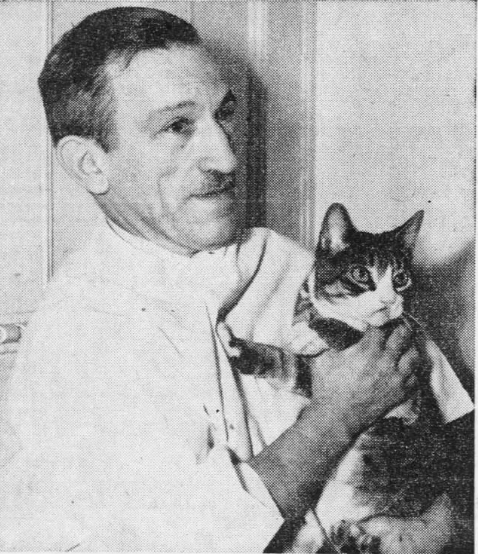

Because Tommy couldn’t take care of himself, Miss Baier assigned Dr. Henry L. Hirscher, a veterinarian who operated the Cat and Dog Hospital at 4351 Broadway, as guardian of the cat. Dr. Hischer had always attended to all of Ms. Baier’s cats at her residence (Tommy was the last cat to survive), so he was quite familiar with the grey tiger cat.

The will also stipulated that should anything happen to Dr. Hirscher, the cat would be sent to the Ellin Prince Speyer Hospital for Animals. The income from the trust would be paid monthly to Dr. Hirscher for Tommy’s care and eventual burial costs. Upon Tommy’s death, any remaining funds would revert to the estate.

Unfortunately for Tommy and Dr. Hirscher, New York County Surrogate Court Judge James A. Delehanty did not find it appropriate for a cat to get an inheritance. The mean judge declared that the disputed trust fund was illegal and that Tommy could no longer collect on it.

According to reporter Eleanor Booth Simmons, Tommy lost his trust fund due to a technicality. According to Simmons, Miss Baier had left the $5,000 to a man named Franklin Hebberd Jr., directing that the sum be held in trust for the cat until Tommy’s death. The weak point was the fact that the trust depended on the cat to keep on living.

K. Courtenany Johnston, a New York lawyer who liked cats, looked into the matter, as he sympathized with people who did not want to leave their pets destitute following their deaths. He thought that establishing an annuity might be a solution, but insurance companies explained that there was not enough longevity information on animals to prepare the necessary actuarial tables. The best plan he found was to charge the estate with the support of pets.

Dr. Hirscher, who had been charging $3 a day for Tommy’s care (because he was a “hospital case”), said he would continue to care for the cat. “He’ll have the run of the house,” the vet told the press. When Ms. Simmons checked on Tommy a year later, he was sprawled across the floor as if he owned the place.

At this time, Tommy weighed 19 pounds. He had his own room, 7×14 feet, and slept in a wicker basket. He also had full access to a yard on the property.

“Paid or not, I’ll be glad to take care of Tommy until he dies,” Dr. Hirscher told the reporter. The vet explained that Ms. Baier had always employed him for her cats and she loved Tommy and wanted the best for him.

According to Dr. Hirscher, Ms. Baier took Tommy in off the streets on a rainy night in 1935 when he was just a kitten. He had always been a sickly cat and suffered from abscesses. When Tommy got a large abscess on his nose, other vets told Dr. Hirscher to put him to sleep. He chose to operate instead, which cured the cat but left a hollow spot on his nose.

In addition, Tommy also suffered from eczema. The vet tried to get him to eat more beef by mixing it with crumbled crackers, but the cat would just eat the crackers and leave the meat. “Queer for a cat,” Dr. Hirscher said, adding he was trying to get Tommy on a good diet even though it was challenging.

Tommy didn’t like dogs and he didn’t like taking his pills. Whenever he didn’t like something, he’d give out a verbal warning and then he’d pull out the claws. Hopefully he lived a happy and healthier life with the vet.

A Brief History of 1384 Riverside Drive

Louise Baier came from a family of talented German musicians. She had several siblings, including a younger brother, Julius W (also a choir singer), from whom she inherited the frame house on Riverside Drive. (Julius had purchased it from George Smith in 1917.) Louise’s other brother, Charles, was also musical; he played the organ at the church.

Louise and Charles lived together in the house at 1384 Riverside Drive in their last years of life (Charles died in 1935). Apparently several cats, in addition to Tommy, lived here also throughout the years.

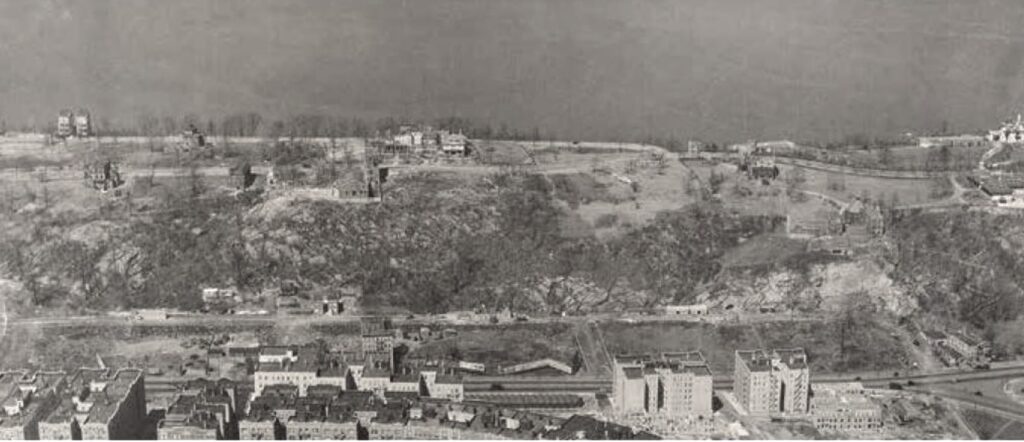

Two hundred years before Tommy Tucker temporarily inherited $5,000, the range of hills on the ridge overlooking the Muscoota (Harlem River) was a hunting place of the Weckquaesgeek tribe, whose largest village was Nipinisicken on the Spuyten Duyvil hill.

In 1673, the first road was cut through this woodland then known as Jochem Pieter’s Hill or the Long Hill, probably following an old hunting trail along the present line of Broadway (the locals called it Breakneck Hill).

Sometime around the late 1690s, a magistrate by the name of Joost Van Oblinus acquired a large tract of cleared land called the Indian Field or Great Maize Land, which extended along the new road from about 165th to 181st Street. In 1769, his grandson Johannes sold about 100 acres of this land to Blazius (Blaze) Moore, a well-known tobacco merchant who had a business at Broadway and John Street.

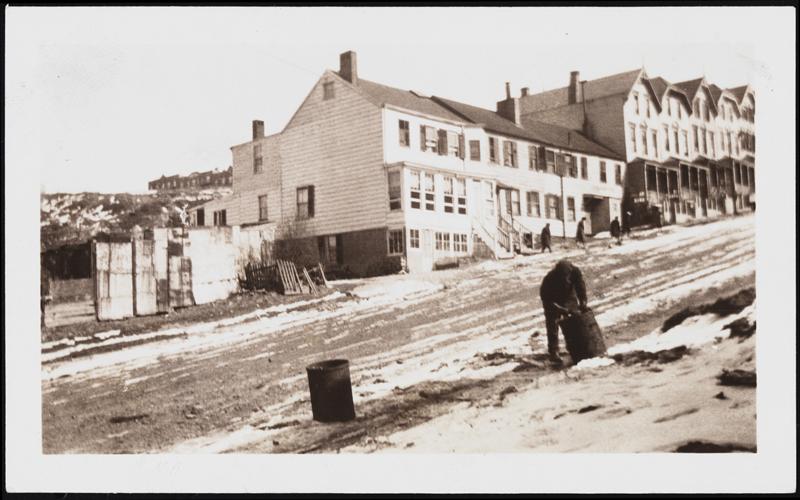

When the Baiers’ house was first constructed on the former lands of Blaze Moore sometime between 1913 and 1917, Washington Heights was still fairly rural. There were a few brick apartment buildings popping up here and there, but as the photo below shows, there were still many frame houses in the area and lots of empty land to develop.

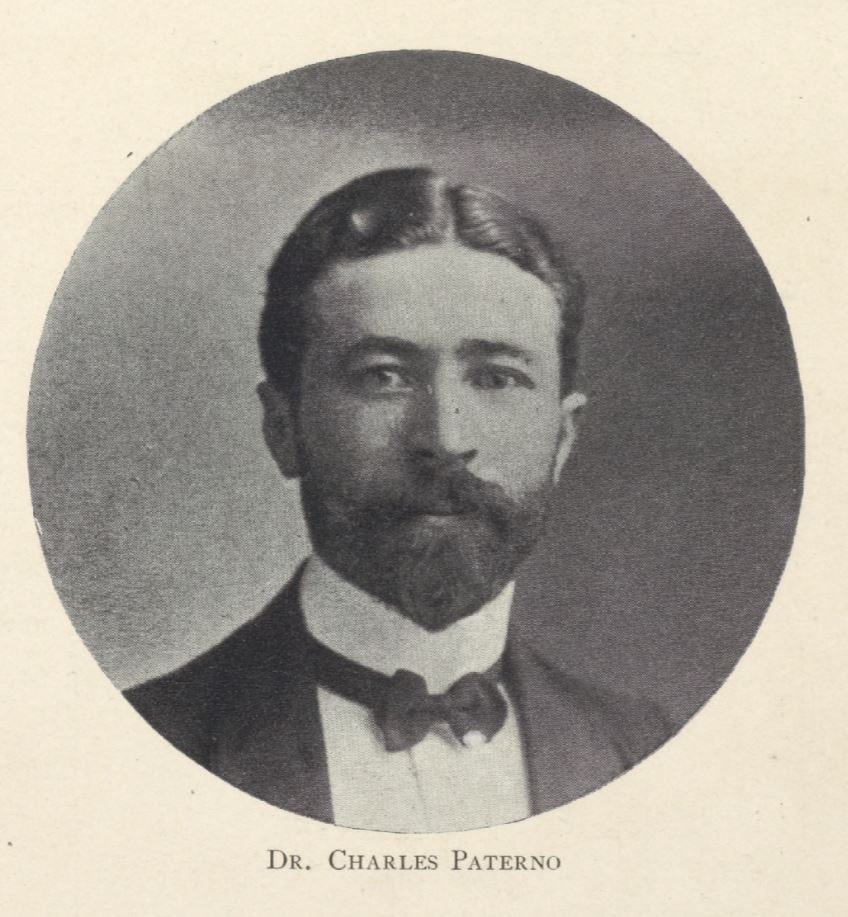

Right about the time the frame house on Riverside was being constructed, a millionaire by the name of Dr. Charles V. Paterno was completing his four-story, 35-room, white marble castle just above Riverside Drive. The stone walls dwarfed the frame house, but at least it didn’t obstruct the Baiers’ view of the river.

Dr. Paterno and his brother Joseph were the sons of John Paterno (d. 1899), a prominent contractor who built numerous apartment buildings on Manhattan’s upper west side. Charles had just received his degree of doctor of medicine from Cornell University, and 18-year-old Joseph was still completing high school, when they were called upon to take over their father’s business and complete those projects he had started before his death.

Over the years, the brothers erected numerous 10- and 12-story apartment buildings in the Morningside Heights neighborhood.

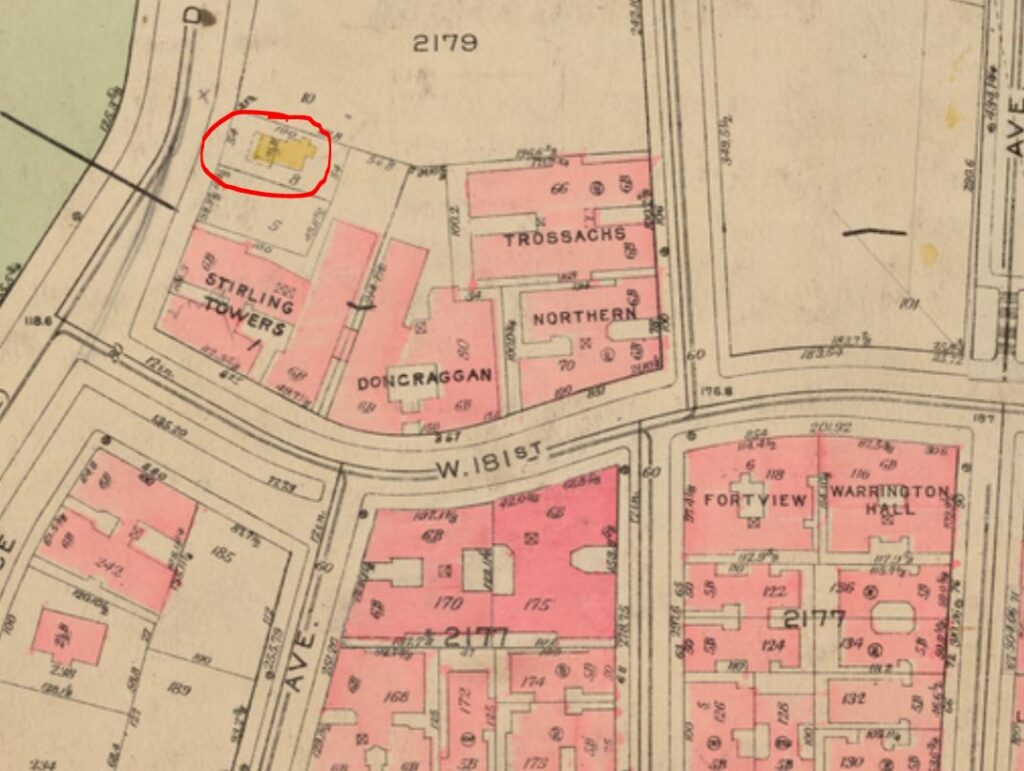

In 1905 Dr. Paterno purchased seven and a half acres of land, about 125 feet above the Hudson River. He commissioned architect John C. Watson to design his new home, or should I say castle. The mansion was between today’s 181st and 185th Streets on what was then called Boulevard Lafayette (an extension of Riverside Drive) and Northern Boulevard (later called Cabrini Boulevard).

The castle did not last long and it did not have a fairy tale ending. Dr. Paterno moved to Greenwich, Connecticut, and in 1938 he razed the castle and most of the rest of the estate to erect Castle Village, a large complex of five 12-story detached apartment houses. How boring.

In 1939, Louise Baier passed away and Tommy moved out of his castle and in with Dr. Hirscher. That same year, Riviera Apartments, of which Morris Halpern was president, purchased 1384 Riverside Drive from the New York Trust Company for $37,000. Plans were filed to construct a six-story apartment house with 49 apartments and 125 rooms on the site at a cost of $125,000.

Dr. Paterno died in 1946, just eight years after he tore down his castle.

If you enjoyed this cat story, you might enjoy reading about Dunder, the Carnegie Hill cat who inherited a fortune in 1925.