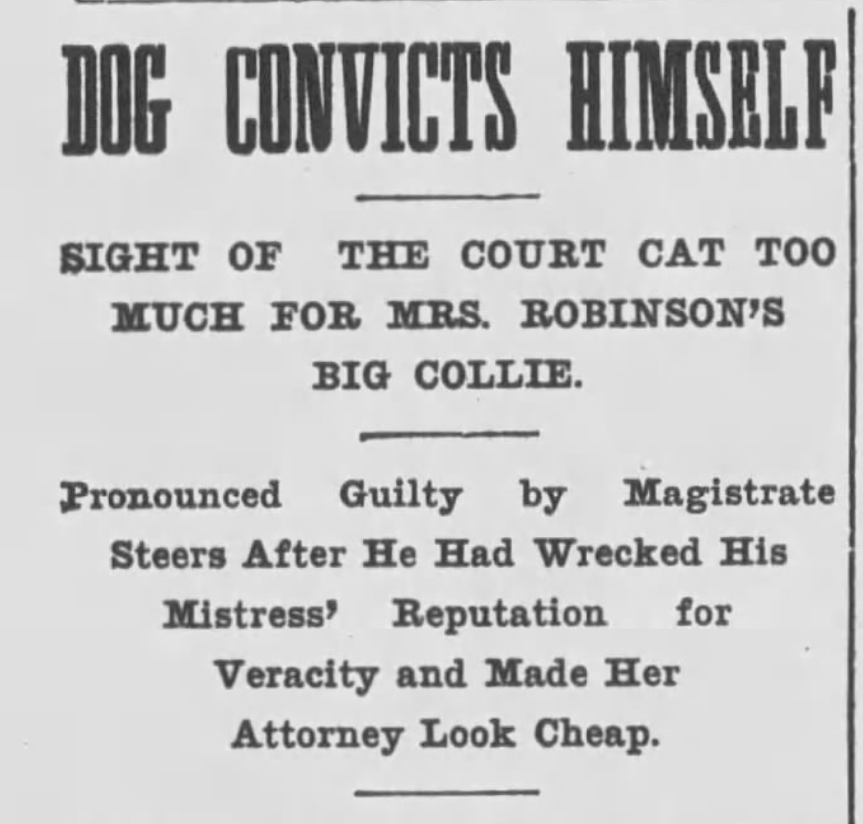

In December 1902, a large collie dog who was a defendant in the Grant Street Court convicted himself by his behavior. His poor behavior was in response to the appearance of Judy, the vigilant court police cat.

According to the Brooklyn Daily Times, the dog had been charged with “viciousness” by Mrs. Charles A. Rohmann of 471 East 27th Street. Mrs. Robinson told the court that the dog had bitten her little boy and four other children in the neighborhood. She presented the court with a doctor’s certificate showing that her child had been treated for a severe dog bite.

The bad dog was owned by Mrs. Mary Robinson, who lived at 459 East 26th Street. She insisted that the dog was “lamblike” and that he was too young to bite people.

“Your honor, I’m all alone my house, my children are away at boarding school, and I must have protection,” Mrs. Robinson told Magistrate Alfred E. Steers. Her lawyer concurred, stating the three-month old pup was a quiet little fellow who would do no harm. (I’m not sure how a lamblike, harmless dog would be a good guard dog…)

Immediately following these opening statements, the Grant Street police court cat made her appearance.

Judy began her career as a court cat in April 1900, when she surprised a sergeant by jumping on his shoulders just as he was telling a prisoner that he had to be searched. The doorman put her outside, but Judy came right back in.

The sergeant, who was superstitious, did not want the cat to come back a third time; he thought it would be bad luck, so he let her stay. And so two times was a charm and stay she did.

When Captain William Knipe of the Grant Street police station (then the 67th Police Precinct) inquired about the cat, Judy jumped on his shoulders, too. She refused to jump off until she was good and ready. Judy was a strong-willed cat who was not to be messed with.

From that point on, Judy had full run of the Grant Street police court. She would walk all over the judge’s desk and the sergeant’s books regardless of whether the court was in session or not, and whenever someone removed her from the court she would promptly return to her chosen spot in the room.

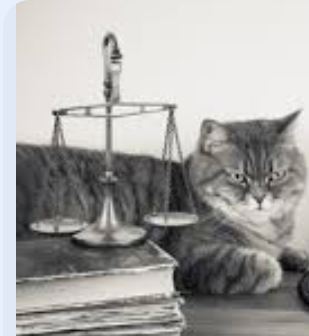

No one knew were Judy came from, but the gray and black tabby was considered a lucky cat on account of her eyes: she reportedly had one black eye and one green eye. She tended to close her green eye when looking at humans, which the judge and police officers took to be a sign of good luck. Despite her shenanigans, the magistrate never called her out of order.

Over time, Judy became a mascot of the Grant Street police court and police station, “and woe would be to the man who harm(ed) a hair of her body”! She became “an invariable attendant upon sessions of the court whenever weighty issues (were) under consideration.” As a court cat, she was “treated with profound respect.”

On the day that Mrs. Rogers appeared in court with her dog, Judy had been conducting her business in another part of the building. Something or someone must have tipped her off that a “weighty issue” was at hand, so she sauntered into the court to investigate the situation.

Seeing the cat, the collie pulled at his chain and sprang at the feline. Judy quickly retreated to the magistrate’s office. The powerful dog was no match for his mistress, who stumbled as he dragged her toward the cat. Mrs. Robinson finally had to let go of the chain, which sent the court into an uproar.

The dog chased the cat all around the office and back into the courtroom. Judy, being much nimbler and more familiar with the layout of the court, easily evaded the collie. She tore down the stairs and took refuge in a jail cell. Court Officer Fox grabbed the dog and chained him to a railing in the courtroom.

Mrs. Mary Robinson promised the magistrate to keep the dog chained or to find a more suitable owner. The court was adjourned for a month, on the grounds that the collie would not be allowed to roam at large during this time. Mrs. Rohmann said she doubted that either Mrs. Robinson or the dog would comply with this order. The final verdict was not published.

A Brief History of the Grant Street Police Court of Flatbush

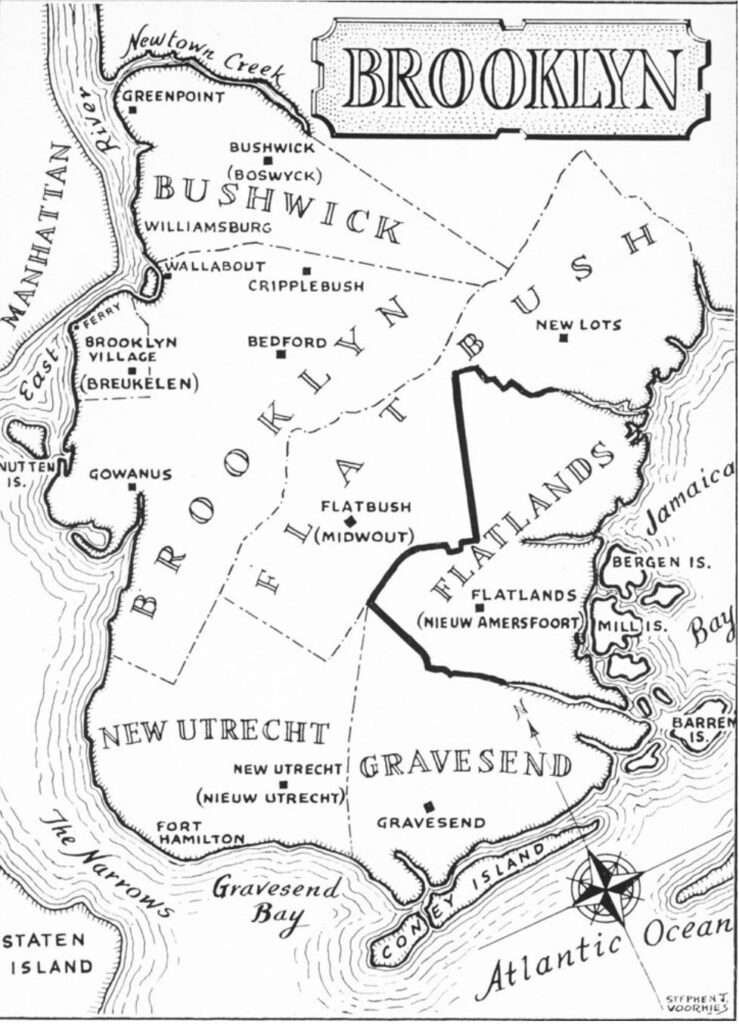

Settlement in the Dutch Village of Midwout, or Middle Woods (today’s Flatbush), began around 1652, although some of the original farms in the area dated back to the 1630s.

Midwout was one of the six towns of Kings County founded under Dutch rule. The others were Breuckelen (Brooklyn), Boswijk (Bushwick), Amersfoort (later, Flatlands), New Utrecht, and Gravesend (an English-speaking settlement and the first in America established by a woman).

The farms of Midwout were originally laid out erratically, and thus, they were not easy to defend. So in 1665, Governor Peter Stuyvesant accepted a plan for a new village with plots set aside for a church, a school, a courthouse, and a tavern. The center of the village was located where today’s Church and Flatbush Avenues now intersect.

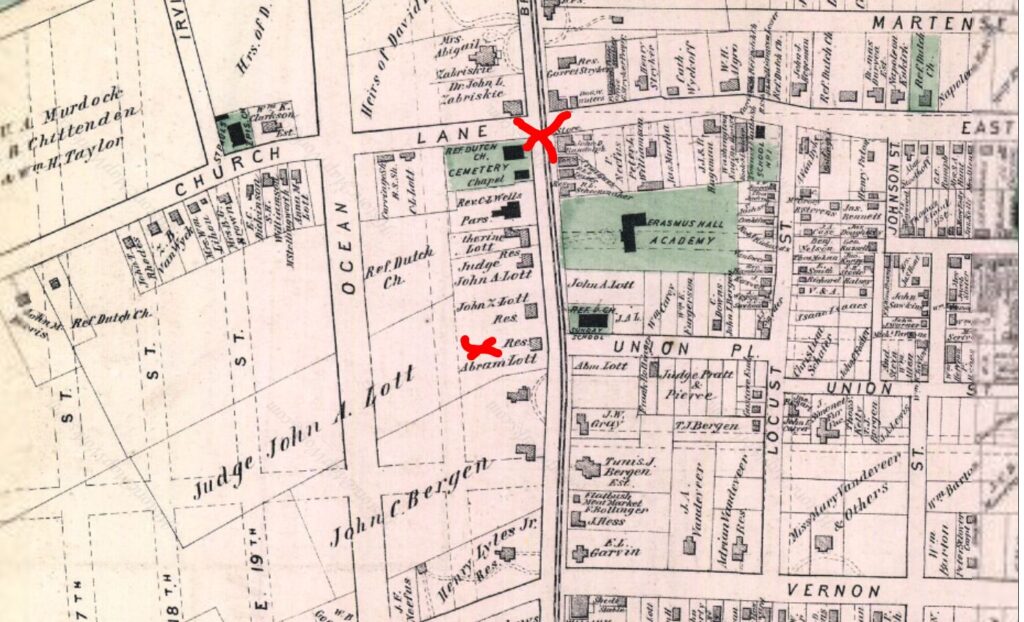

Although the plan approved by Stuyvesant called for a courthouse, the first courthouse constructed in Kings County was actually in Gravesend in 1683, the year the county was formed. It wasn’t until two years later, in 1685, that court services moved to Flatbush on what was called the Court House Lot (later the property of John A. Lott). This lot comprised two buildings housing a court and a separate jail.

In November 1692, the Court of Sessions for Kings County ordered that each town have “a good pair of stocks and a good pound.” The Flatbush stocks and a whipping post stood in front of the jail.

In the winter of 1757, the jail burned down (there is no record whether the stocks and whipping post also burned). The court would have also been destroyed had it not been for some ingenuity: residents threw snowballs on the building, which prevented the fire from spreading.

Following the fire, a two-story structure was built on the site, which had a jail downstairs and a court upstairs. During the Revolutionary War, British soldiers used the court as a ballroom.

In 1792, the court building was sold at auction to Michael Van Cleef, who in turn tore it down and sold the timbers to Reverend Martimus Schoonmaker. Schoonmaker used the timber to build a house on Flatbush Avenue that was later occupied by his son, Stephen.

A larger courthouse and jail was erected on this same site, but this building burned down in November 1832. All of the Kings County court services were transferred to the new City of Brooklyn at this time.

For many years, Flatbush held its elections at hotels and the justices held their courts in either their own homes or in the parlors of hotels. After the public schoolhouse was erected in 1842, elections and court sessions took place on its second floor.

By 1861, the growing town needed the second floor of the school for the children, and so elections, court sessions, and other community events took place at Schoonmaker Hall (893 Flatbush Avenue) for the next ten years.

On February 19, 1874, a group of prominent landowners–including John Lefferts, Gilbert Hicks, Jonas Lott, John Vanderbilt, Dr. J.L. Zabriskie, J.V.B. Martense, John J. Snyder, and Abraham Ditmas–met at Schoonmaker Hall to propose a formal town hall.

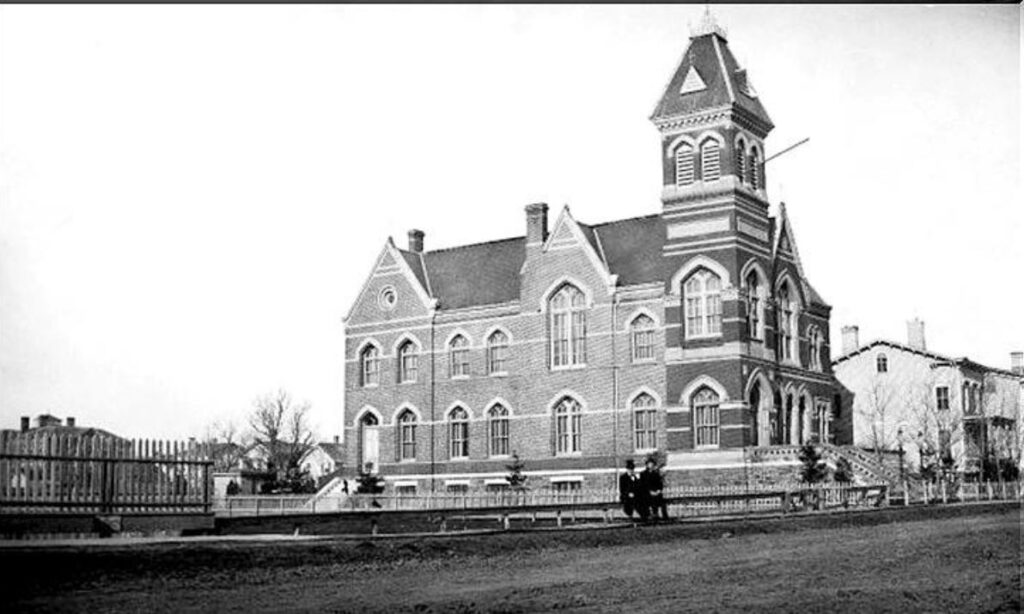

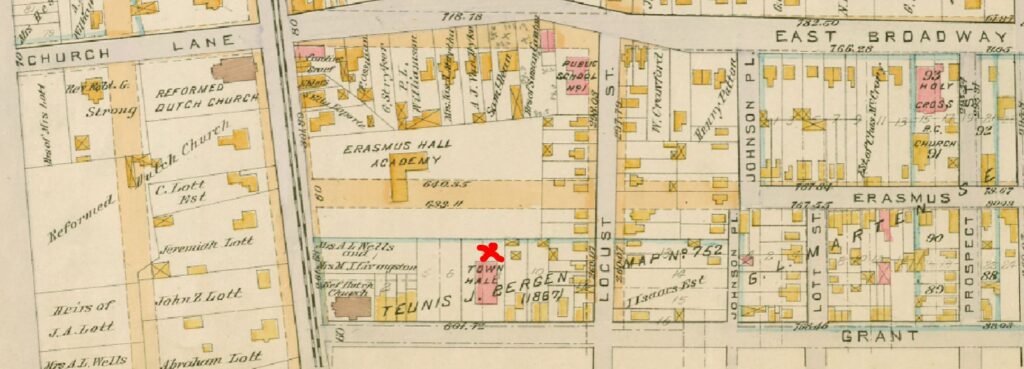

The men formed a Board of Improvement and hired architect Colonel John Y. Culyer to design the Gothic Revival building. The new Flatbush Town Hall was constructed in 1874-75 on a yet-unpaved portion of Union Place (later, Grant Street, and today’s Snyder Avenue).

The Flatbush Town Hall contained offices for local officials and the police force on the ground floor. An auditorium on the second floor was used for public meetings and events and also served as a ballroom.

Down in the basement was what was described as “a repulsive” lockup (which the men hoped would never be occupied by a Flatbush resident). The bell in the tower alerted volunteer firemen of fires using a special code that designated its location.

After Flatbush was annexed into the City of Brooklyn in 1894, the Grant Street building served as a community center, magistrate’s court, and the 67th Police Precinct. It was during this era that Judy reigned as the court cat.

The building was mostly vacant from 1924 to 1926, but in 1926 the old town hall was renovated to house the new 82nd Police Precinct. The police force moved out in 1972, which is the year the old building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Today the former Grant Street court and police station serves as a public school focused on special education needs.

Thank you for this wonderful story! What a captivating blend of rich historical detail and engaging storytelling. It really drew me in, transforming it into more than just a tale—but an immersive journey through time. A truly impressive and enjoyable read! I always learn so much from your work.