Mrs. Mary Hall lived in the large, 5-story brick tenement at 59 East 41st Street. Mrs. Anna Staubstaudt lived next door, in a 3-story brick building with stables at 57 East 41st Street.

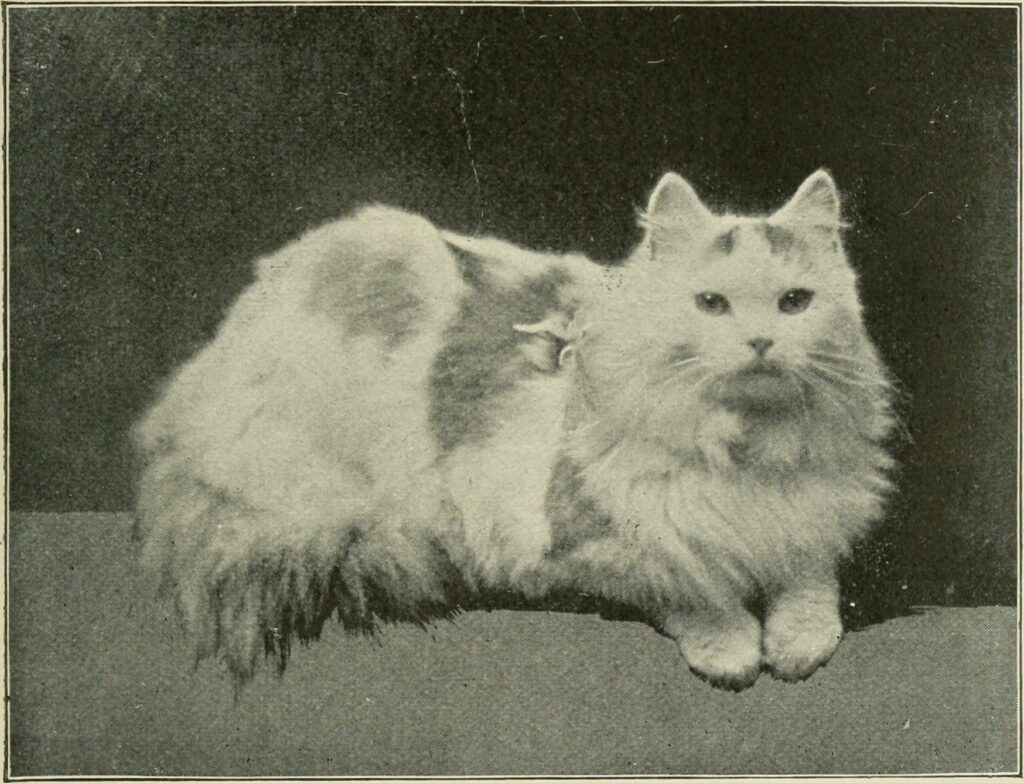

Mrs. Hall had a large Angora cat named Tommy. Mrs. Staubstaudt had a male cat and female cat “of the plain backyard variety.” The three cats fought often, with the plain male cat, Benny, taking most of the hits and scratches from the Angora.

Tommy was a cat of remarkable beauty, but he also had strong lungs and fighting qualities. Mrs. Hall acquired the cat in 1887, and though he often wandered the neighborhood looking to stir things up, he always returned home. That is, until the summer of 1895.

On June 16, 1895, Tommy disappeared. Mrs. Hall searched all over the house for him. She also asked all the neighborhood boys to search for him on the streets.

With a long summer trip to her country home already planned, Mrs. Hall could do nothing but leave a couple of windows open so Tommy could get back inside. She also kept one door unlocked, and asked two friends to ship him to her country house as soon as he returned to the East 41st Street home.

For four months, Mrs. Hall waited to hear news of her cat back in the city. When she returned in mid-October, she learned that Mrs. Staubstadt had Tommy “imprisoned” in her house. Mrs. Staubstadt refused to give the cat back, and even had the gall to charge Mrs. Hall for boarding the cat for the four months that she was away, the woman alleged.

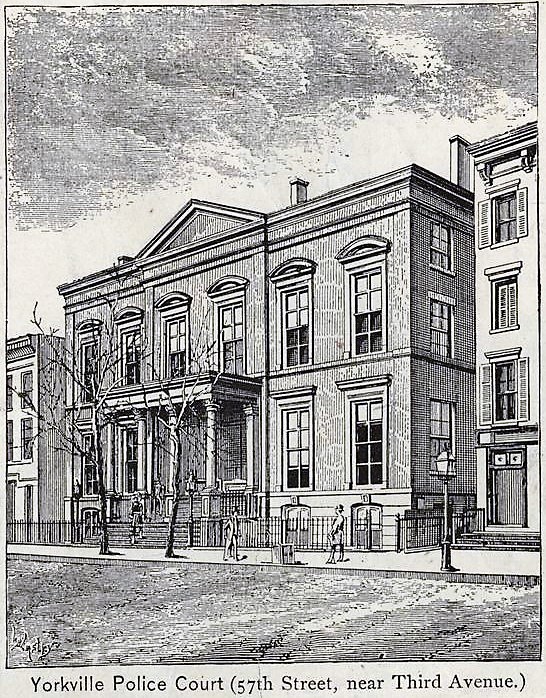

Mrs. Hall filed a criminal lawsuit against her neighbor to get the cat back. The hearing took place at the Yorkville Police Court before Magistrate Henry A. Brann.

“Have you that woman’s cat?” Magistrate Brann asked the cat-napper.

“Yes, I have,” Mrs. Staubstaudt firmly replied, according to The New York Times.

Then the judge made the mistake of asking her why she had not returned the cat to Mrs. Hall.

“This cat came to my house almost starved ten days after Mrs. Hall went to the country. The cat never had enough to eat.”

“What!?” shrieked Mrs. Hall. “How dare you! You stole that cat. You were always jealous of my cat.”

“I took your cat in and fed him as an act of charity, and he repaid it by clawing the fur of my dear Benny. If you think so much of Tommy, why don’t you pay for his board?”

For the next few minutes, the two women argued back and forth until Magistrate Brann jumped out of his seat and cried, “Stop!”

He told Mrs. Staubstaudt to return the cat to Mrs. Hall, but her attorney, John H. Whitney, protested. “This woman has a lien on the cat for board, the same as in the case of a stray horse picked up and boarded,” the lawyer said.

“Pshaw! Pshaw!” the magistrate retorted. “If you want to collect for the board of this cat, bring action in the civil court. Go home and get your cat, Mrs. Hall,” he said.

Then addressing Mrs. Staubstaudt, he said, “You return this woman’s cat. You have no right to it.” Cat case dismissed.

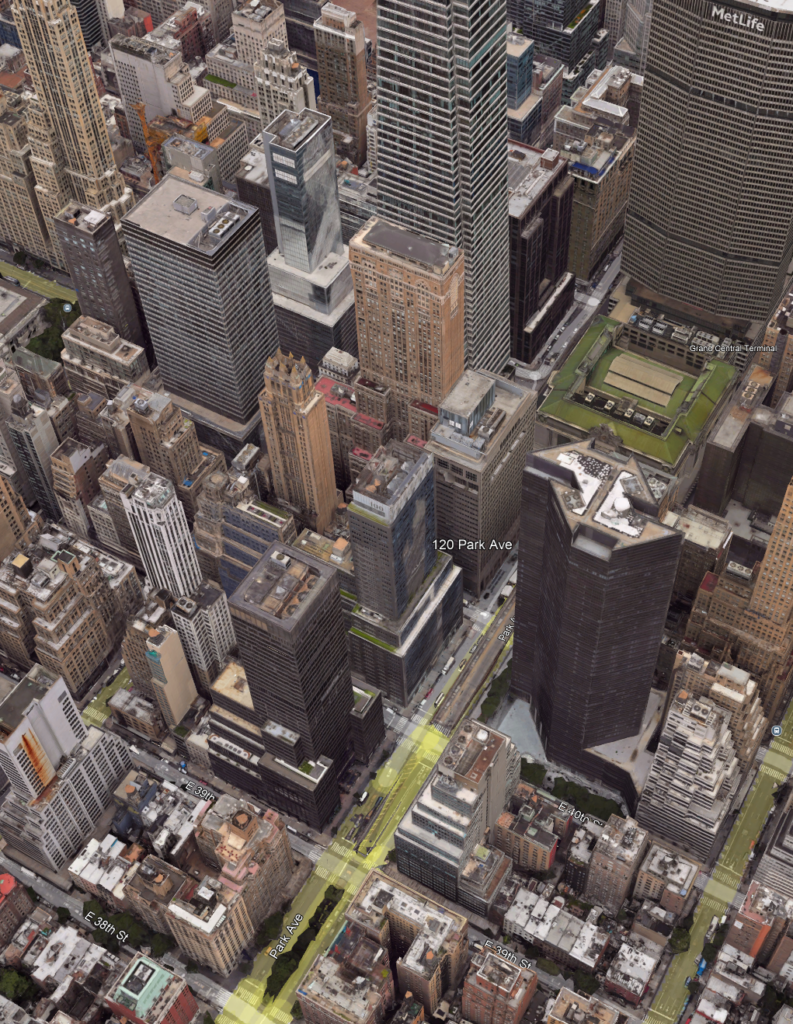

A Brief History of Park and 41st Street

The apartment buildings where Mrs. Hall and Mrs. Staubstaudt lived on East 41st Street occupied the northern edge of the former 19th-century farm of James Quackinbush (aka Jacobus Quackenbos) in the Murray Hill neighborhood.

Born in 1758, James Quackinbush grew up in Tappan, New York, and served as a sergeant during the Revolutionary War. Immediately following the war, he married Leah (Lea) Demarest and got into the family business. James owned and operated a dry goods store on William Street, and he and his growing family lived in lower Manhattan.

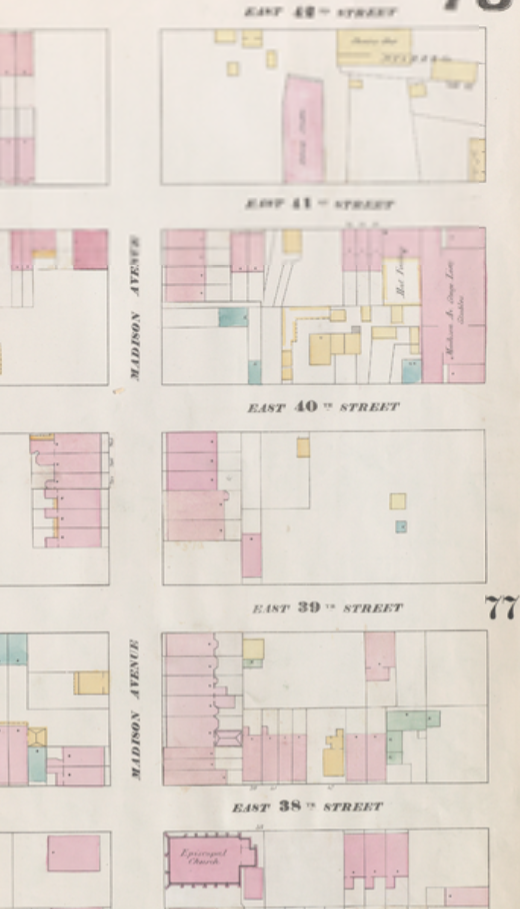

On August 5, 1803, James acquired the title for a 15-acre farm from Thomas Cooper, Daniel McCormick, and Charles Smith for $12,700. The farm was bounded by today’s Lexington and Madison Avenues, 38th Street and 41st Street.

The Quackinbush homestead was near the intersection of present-day Park Avenue and 40th Street. Their nearest neighbor was Robert Murray, whose country seat at what he called Inclenberg (Fire Beacon Hill) was at Park Avenue and 36th Street.

By the time James purchased the farm, the family had 10 children: 8 boys and 2 girls ranging in age from 19 to 3. The younger sons–Benjamin, Andrew, and Abraham–enjoyed digging for potatoes on their farm, right about where Grand Central Station is today. Sadly, two years after they moved to the farm, Leah Quackinbush passed away at the young age of 41.

Beginning in 1832, the construction of the New York and Harlem Railroad streetcar line along Fourth Avenue (Park Avenue) accelerated development of Murray Hill. Although Fourth Avenue north of 34th Street was still an unpaved road leading through farmland and shantytowns, it began to open up northward. By 1848, it had opened all the way through the Murray’s land to 38th Street.

Sometime after Leah passed away, James married Margaret Fake (they did not have any children). Despite all the development taking place around his farm, James continued to live at his Murray Hill home until his death on January 17, 1842.

Following his passing, the farm was divided into lots and sold at $150 per lot. New Yorkers were still not quite ready to head so far north, so sales were slow at first.

Shortly after James passed away, the family home burned down. But by 1857, as shown on this map at left, much of the old Quackinbush farm was still undeveloped.

The apartment buildings on East 41st Street where the two feuding cat ladies were living in 1895 had not yet been built either, although the Quackinbush home had been replaced by the large stables of the Madison Avenue Stage Line. This popular stage line ran between the South Ferry and 42nd Street.

In 1884, the Murray Hill Hotel was built on Fourth (Park) Avenue, right atop the site of the stage line stables and former Quackinbush homestead between 40th and 41st Street.

Less than 20 years later, the Murray Hill Hotel had competition from the much taller Hotel Belmont, which was constructed on Park Avenue between 41st Street and 42nd Street. It was one of the city’s tallest hotels at 23 stories.

On August 30, 1930, the newspapers reported that the city’s tallest office building–60 stories–would replace the Hotel Belmont. Although demolition began in 1931, the hotel sat vacant until 1934, when it was replaced by the Airlines Terminal building.

The older and shorter Murray Hill Hotel was razed in 1947 to make way for another modern office building. More than 100 people who had been living in the old hotel were forcefully evicted from the building in April 1947.