When Cheechee disappeared from the Central Court Cigar Store at the corner of Schermerhorn and Smith Streets just a few weeks before Christmas in 1949, everyone in the neighborhood lost some of their holiday cheer. Kids from one to 92 would not have a merry Christmas until Santa brought her back safely.

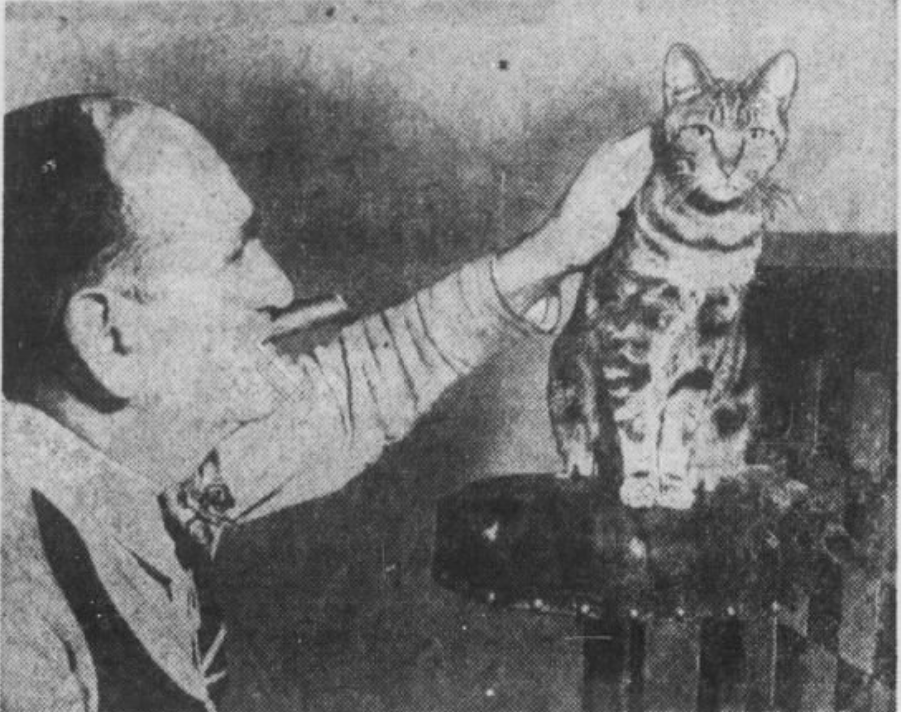

Cheechee was a lovable cat and good friend to all the Central Courts Building judges, lawyers, prosecutors, and court clerks who purchased their cigars at David Karp’s shop. The children who bought candy and chocolate sodas at the store’s ice cream counter also loved the sociable tiger cat.

Cheechee moved into the cigar store at 50 Smith Street and made it her home in 1941. She spent much of her time at the newsstand, but she also had her own stool at the ice cream counter–even when all the stools were occupied, no one ever thought to make Cheechee give up her seat to a paying customer. Everybody knew that this was the cat’s stool, and no one else could sit there. (Perhaps Cheechee was related to Rusty, the Algonquin Hotel cat who also had his own stool, albeit, his was a bar stool.)

Cheechee disappeared at 6 p.m. on December 2, which is when Mr. Kern last saw her go for a walk wearing her fur coat of gray and white tiger stripes. After she didn’t return home the next day, Karp began asking everyone to look out for her and call her name.

One of the people who learned of Cheechee’s disappearance was Mrs. Amber Davis, a telephone operator in the nearby Children’s Court at 111 Schermerhorn Street. Mrs. Davis was quite fond of the cat, who often followed her into the court and sat in on the proceedings, “solemnly listening as if trying to help the judge arrive at a just decision.”

As soon as she heard that Cheechee had not returned home, she contacted the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and requested the newspaper run a story about the missing cat.

“If you see the tiger stripes, call ‘Cheechee!’” Mr. Karp told Mr. Kaufman, the reporter who came to interview the store owner and Mrs. Davis. “If the lady cat thus addressed obviously recognizes her name and answers to it, comes right up to you in a friendly manner, that’s Cheechee.”

One day after the story about Cheechee appeared in the newspaper, the cat returned to the cigar shop and sat down at the counter on her regular stool. It was as if she had never left. The reporter said her reappearance provided “a new, convincing demonstration of the influence, it not the power, of the press.”

“She is well fed and in good condition, as if she had been well treated by someone in the neighborhood, who let her go after reading the story of her disappearance,” Mrs. Davis said. “But you know what? I wouldn’t be surprised if it turned out that Cheechee was just wandering around and that she read the story—on some other newsstand, of course—and decided to come back.”

I wouldn’t be surprised if a child took Cheechee home to be their pet, and when Mom and Dad read the newspaper, they told the child to return her. But maybe Cheechee did read about her own disappearance, or perhaps Santa checked his list twice and performed some of his magic to bring her back… we can all have fun imagining that one of these events happened.

A Brief History of the Children’s Court

The hero of this cat story is Mrs. Amber Smith, who worked as a telephone operator at Brooklyn’s Children’s Court on Schermerhorn Street. If she hadn’t reached out to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Cheechee may have been lost forever.

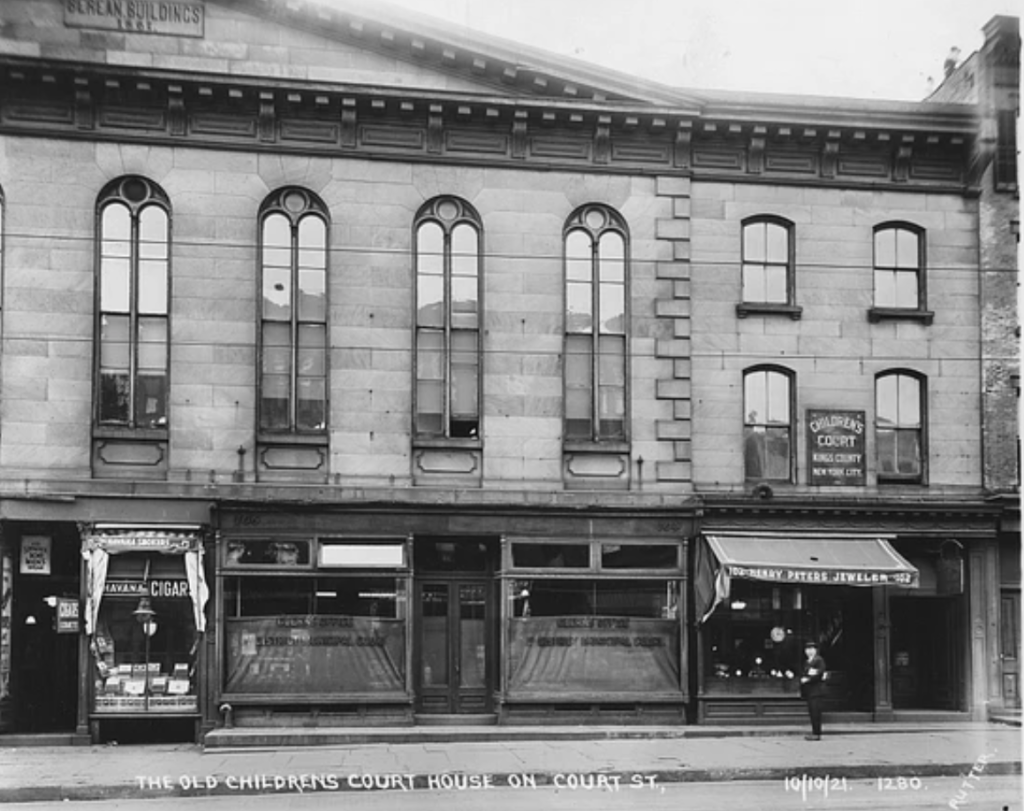

The original Brooklyn Children’s Court opened at 102 Court Street on September 8, 1903. The bill creating the court was signed April 14, 1903, by Governor Benjamin Baker Odell. The next day, Mayor Seth Low appointed Robert J. Wilkin, superintendent of Brooklyn’s Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (SPCC), to serve as a justice presiding in the new Children’s Court.

The official name of the court was the Municipal Court, First Division: Children’s Court. It was located on the second floor of the circa 1867 Berean Building, which once housed Brooklyn’s branch of the New York Conservatory of Music. From the 1890s to 1903, the building was occupied by a theater called Apollo Hall, which was home to acting and dancing schools and political and social clubs.

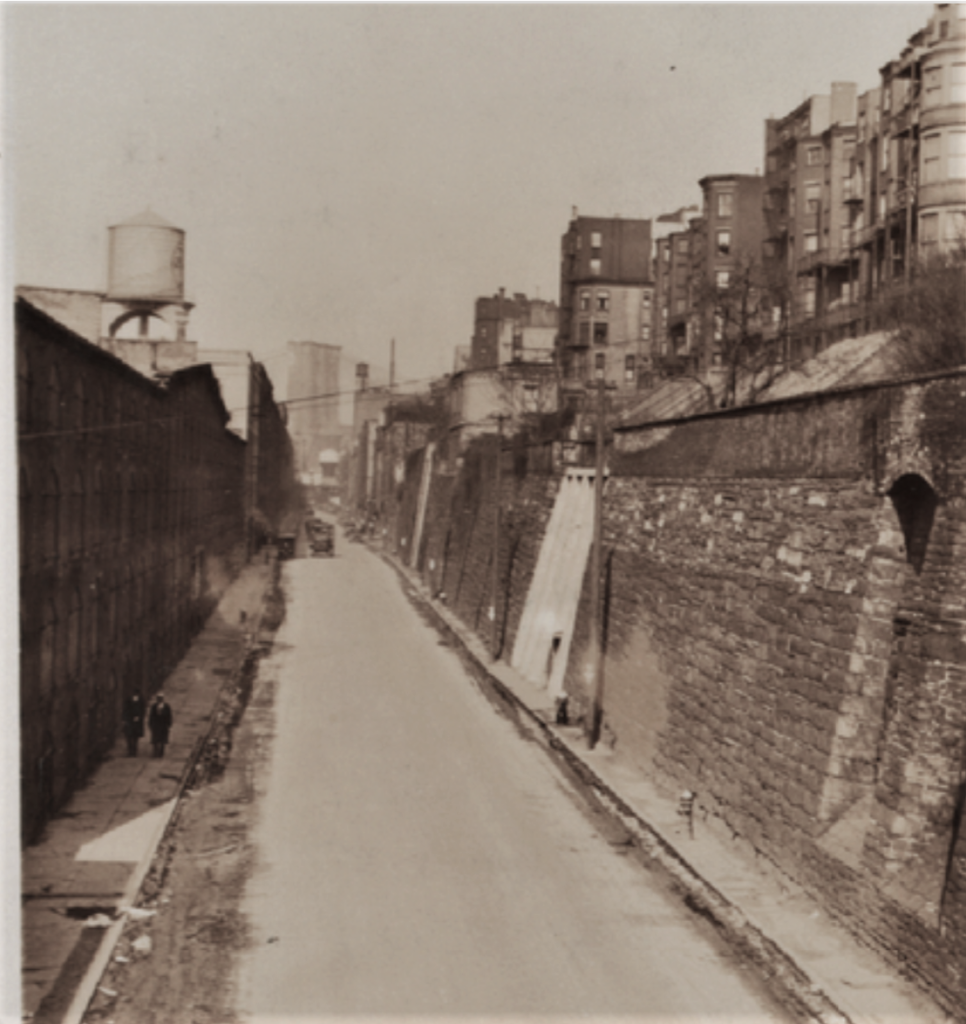

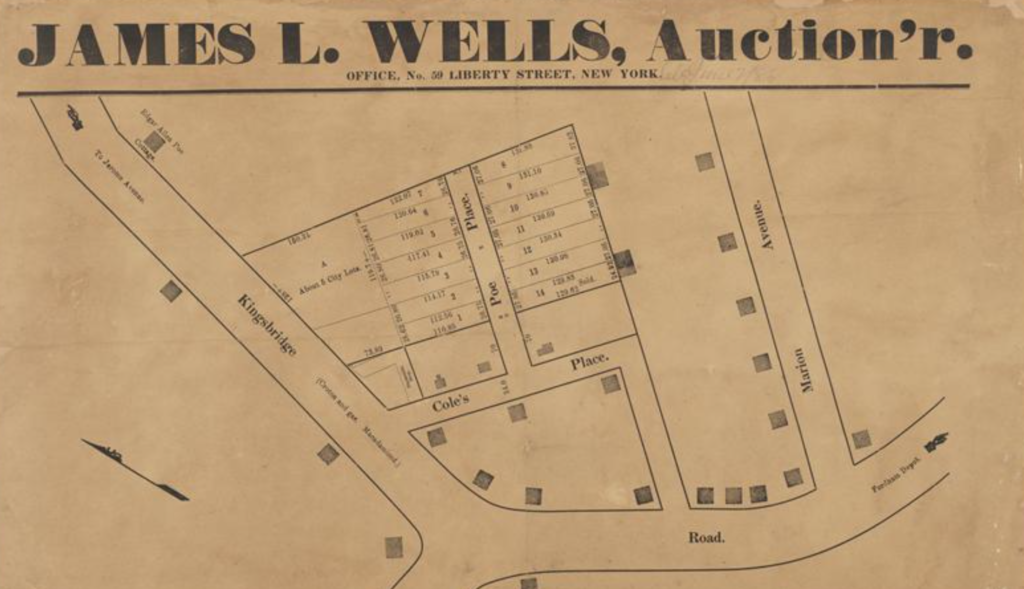

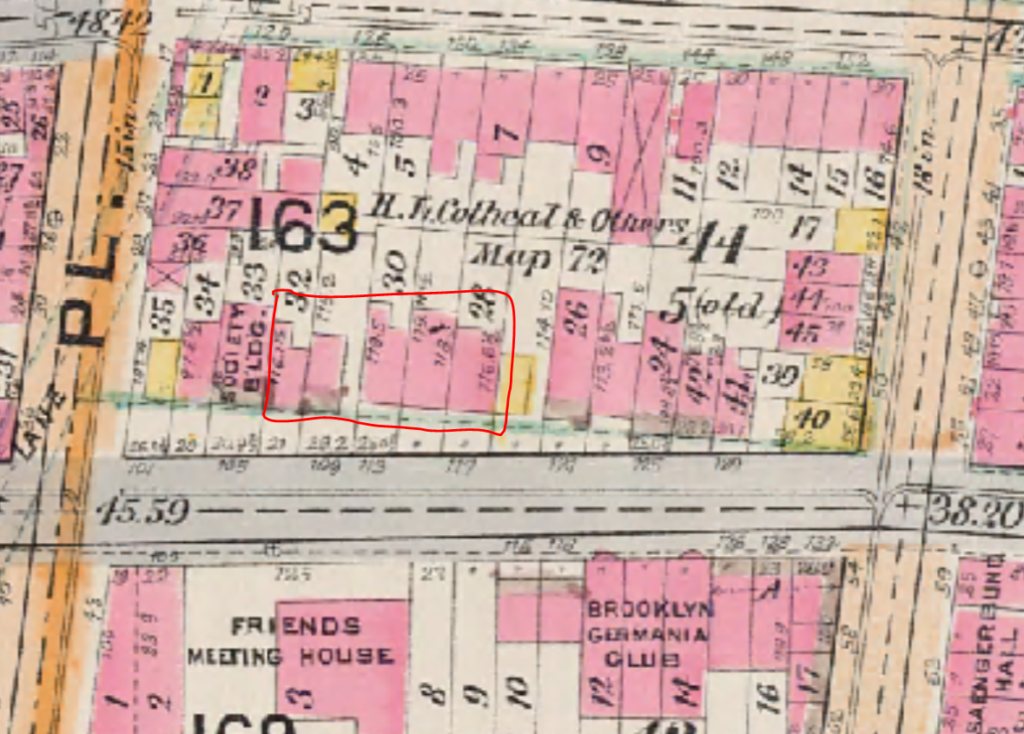

On March 13, 1917, Edmund W. Voorhies, Acting President, Borough of Brooklyn, requested the designation of a plot on Schermerhorn Street, between Boerum Place and Smith Street, as the site for a new Children’s Court building. The site, which adjoined the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (SPCC) headquarters building at 105 Schermerhorn Street, had been chosen a month before.

“It has been deemed best by people interested in the matter that this court should be constructed on the north side of Schermerhorn street, between Boerum Place and Smith Street,” he wrote to the Board of Aldermen. “I am sending you herewith a map that shows the exact location and size of this plot, and would ask that you have the proper steps taken to have this location designated as a site for the Children’s Court, in accordance with section 47 of the City Charter.”

The site selected for the court was occupied by five brick residential homes, numbered 107-117 Schermerhorn Street. The city was able to immediately secure options to purchase three of the five homes; the houses at 115 and 117 Schermerhorn Street presented a challenge.

When asked why there was a delay in starting construction on the court building, Brooklyn Borough President Lewis Humphrey Pounds said, “Two old maiden ladies refuse to sell to the city their property, which comprises part of the site selected for the Children’s Court.”

The two “old maiden ladies” were Mrs. Elizabeth Eaton Carver Whittier, a mother and wife of Thomas Tupper Whittier, and her sister, Miss Alice G. Chase, who was living in Japan at this time (Mrs. Whittier chuckled when she heard that the borough president had referred to her as an “old maiden.”)

The sisters were the daughters of a Maine ship captain, George A. Carver, and his wife, Virginia Eaton Carver. They were also the granddaughters of James C. Eaton, who owned land on Schermerhorn Street in the late 1800s, including the home at 115 Schermerhorn Street. When their mother, Virginia, died in 1913, the sisters inherited the property.

Mrs. Whittier said she had been waiting to get power of attorney from her sister, as she could not sell the property without her sister’s consent.

“Of course to us it is little less than a tragedy to have to part with this house, which was built by my grandfather, seventy-one years ago, and where I and my sister had expected to reside for the remainder of our lives,” Mrs. Whittier said. “But we realize that the city can take the property by condemnation proceedings, and it would be foolish to let it come to that if the matter can be settled privately on an equitable basis.”

According to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Mrs. Whittier and her sister wanted $18,000 for each of the two homes, but the city was only willing to pay them $14,000 each. A deal must have been made, because a few years later, in June 1920, ground was broken for the new building. By that time, Mr. and Mrs. Whittier and their daughters had moved to 30 Sidney Place.

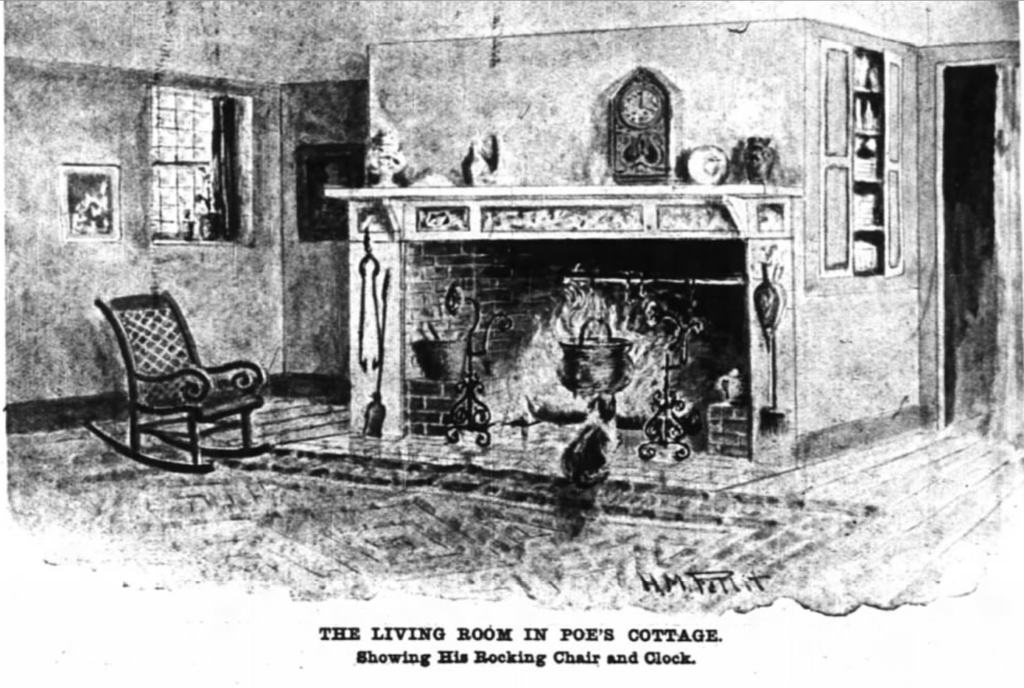

On October 31, 1921, the Children’s Court moved into its new three-story, Federal-style building. Giving a tour of the new court building to a reporter, Justice Wilkin pointed out the offices of the Big Brother Association on the ground floor and the psychiatrist’s office on the second floor.

As Justice Wilkin told the press, no child was considered a criminal by the Children’s Court, and the only law that the court recognized was the law of humanity.

“It is impossible for a child to commit a crime,” Justice Wilkin said. “A child goes wrong only because of his environment. The Children’s Court is a corrective and not a punitive institution.”

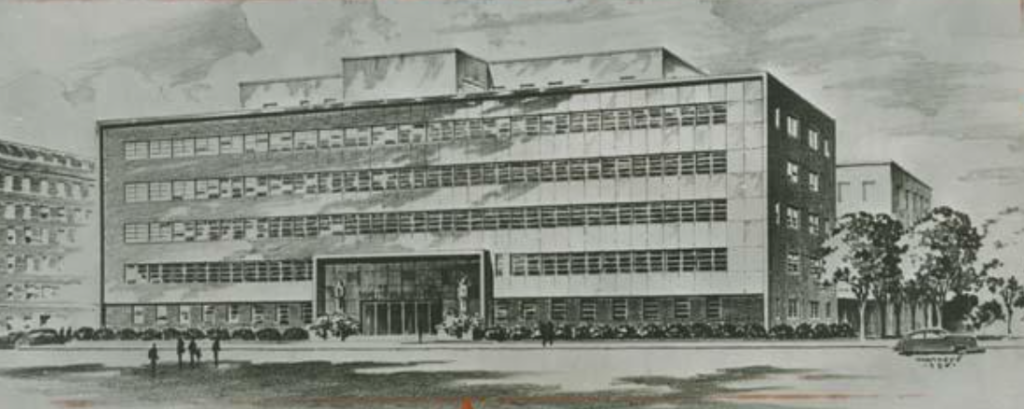

On January 22, 1954, thirty years after the Children’s Court opened on Schermerhorn Street, a cornerstone ceremony for the new Brooklyn Domestic Relations Court Building at 360 Adams Street (Brooklyn Bridge Blvd.) took place. The new six-story building would house the Children’s Court and Family Court, which had become one unit in 1953.

For the next twenty years, the old Children’s Court building was occupied by the Adolescent Court and then the Landlord and Tenant (Housing) Court. The building was demolished in 1974.

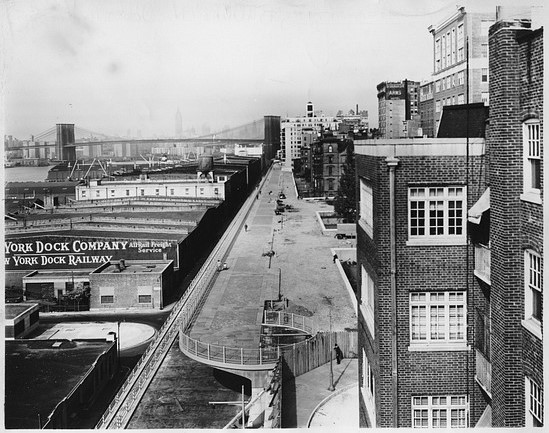

Today, the site of both the old Children’s Court and the Central Court Cigar Shop is occupied by the block-long New York City Transit Authority (aka MTA) headquarters building. The 12-story building was constructed in 1989 and occupies Cheechee’s old stomping grounds–in other words, the entire block bounded by Schermerhorn, Smith, Livingston, and Boerum Place.