I am going to tell this story backwards in order to encourage readers to appreciate the history behind every building, park, and street in New York City. This cat tale of Old New York will start with a look at the Art Wall on the northwest corner of Bowery and Houston Street.

The Art Wall at Bowery and East Houston Street has been a giant blank canvas for numerous artists since 1982, when Keith Haring and Juan Dubose chose this location for a public mural. Much has been written about this ever-changing mural, but does anyone know the real story–the history–of what took place on this site before it became a popular tourist attraction?

The Bowery and the John Dyckman Farm

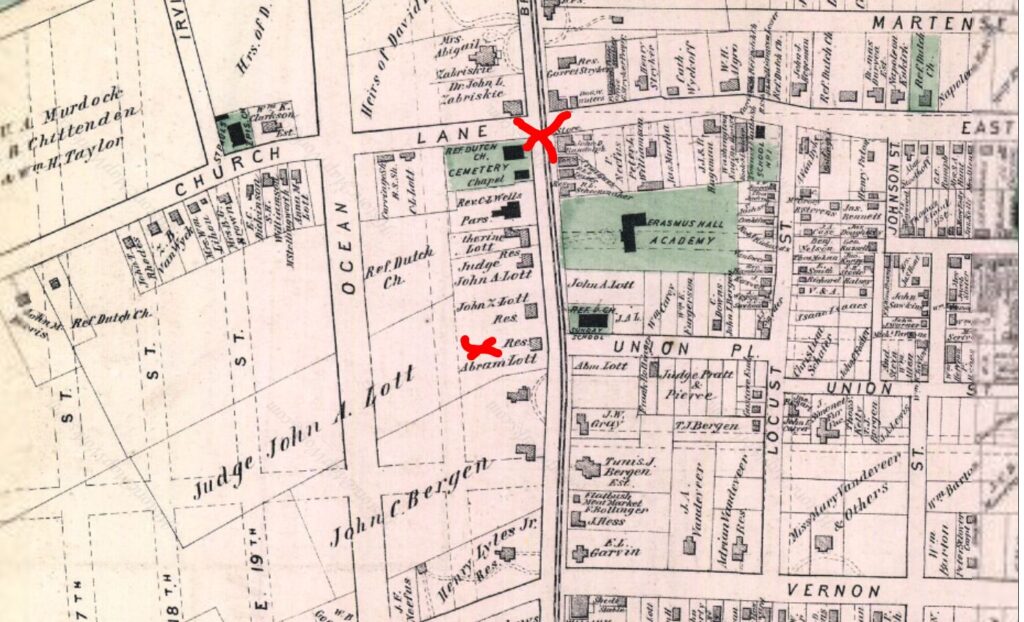

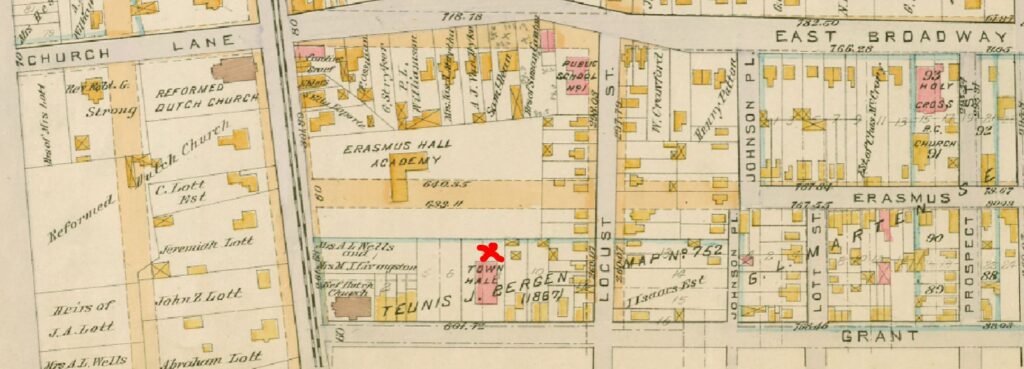

The Bowery was originally a Native American footpath that extended the length of the island through dense woodlands. During the Dutch colonial days, Director Wouter Van Twiller, who served as governor of New Netherland from 1633 to 1637, acquired a 250-acre bowery (a bowery or bouwerie was a complete self-sustained farm, with crops, orchards, and livestock) as part of his compensation package, so to speak. It is on the lands of this bowery that the Houston Bowery Art Wall stands.

Around 1642 or 1643, Director General William Kieft granted parcels of land (about 8 to 20 acres each) along this path to several freed slaves who had served the government from the earliest period of the Dutch settlement. Other parcels were granted to “free negroes” in the 1660s by Governor Richard Nicholls and Peter Stuyvesant.

Over the next 100 years, these lands passed through various hands and were combined to create much larger farms owned by prominent settlers such as John Dyckman, James Delancey, and Nicholas Bayard. The Bouwerie Lane that connected these farms was anglicized to Bowery Lane and later, Bowery Street or the Bowery.

Alderman John Dyckman owned a large estate of irregular boundaries from Prince to Bleecker Streets along the Bowery to Greene Street. The Dyckman house was west of the Bowery Lane about 150 feet north of East Houston Street. When Alderman Dyckman died in the 18th century, his property was bequeathed to his nine children.

The History of 286 Bowery

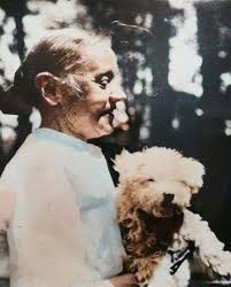

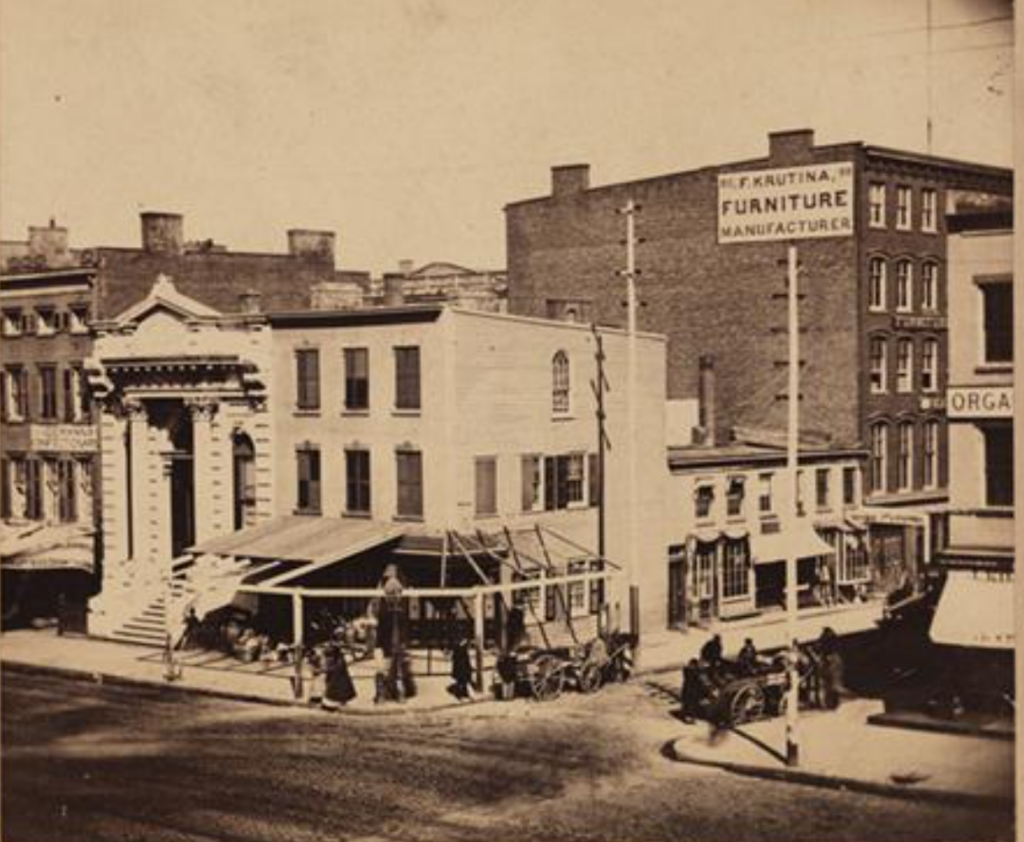

The Capitol Saloon, where the cat in this story resided during the early 1900s, was located at 286 Bowery, on the northwest corner of E. Houston Street. The building was constructed sometime prior to 1830 on the old Dyckman farm, less than one block south of the Dyckman farmhouse.

The history of this building is fascinating: as the saying goes, if these [art] walls could talk…

- In the 1830s and 40s, the ground floor of the building was occupied by a medicine shop that was reportedly the only place in the city where one could buy Dr. Henry’s vegetable rheumatic syrup. In the 1830s, Dr. Stewart also advertised that one could purchase a remedy for “female complaints” at this shop.

- In the 1850s and early 1860s, 286 Bowery was a pianoforte showroom (pianos and organs) owned by Samuel Utter, where a young lady gave piano lessons. Also during the 1850s, the building housed Vosburgh’s teas and groceries and a wine store owned by L. Monzert (in 1853, Henry Beck, a German bartender at this wine store, was killed after falling down the cellar stairs).

- During the 1860s, the building housed a coffin manufacturing shop. Business must have been brisk, because the owner often advertised for two or three “good coffin makers.”

- Mr. and Mrs. Jesse Toothaker also had a dress shop at 286 Bowery in the 1860s. They sold a new patent life-preserver skirt, cheap (I don’t know what this is, but I wouldn’t depend on a cheap life-preserver dress to save my life!).

- By the 1880s, this Bowery building was four stories tall and owned by Emile F. Scharff, who had a bakery and candy store on the ground floor and lived with his family and servants on the upper floors. In 1885, a fire caused by an overheated chimney destroyed the top two floors; all 15 people were able to escape.

- Also during the 1880s, it was a saloon operated by Adam Bischer and then a saloon owned by George H. Werfelman. Brian Hughes, the greatest prankster of New York City who once fooled the judges at the city’s first official cat show, also had a paper box factory in this building during this time.

- In 1893, a bootblack named Frank Deorio, who did a brisk business with the police detectives, set up shop in front of 286 Bowery. One day, Frank went missing and never returned to his spot. It turned out that Frank had deserted his wife and two young children to elope with his 22-year-old house servant, Carmella. The neighborhood was “agog” over the scandalous news.

The Capitol Hotel Mascot Cat

And now to the cat story part of this historical Bowery review!

In the early 20th century, a newspaper reported that stray cats in New York did not have to remain on the street if they didn’t want to. Most New Yorkers who wanted a cat could simply choose one off the street, and as long as they fed it enough, that cat would have a home. But for a mangy cat it was not that easy. Most mangy cats seemed to know that they belonged on the Bowery.

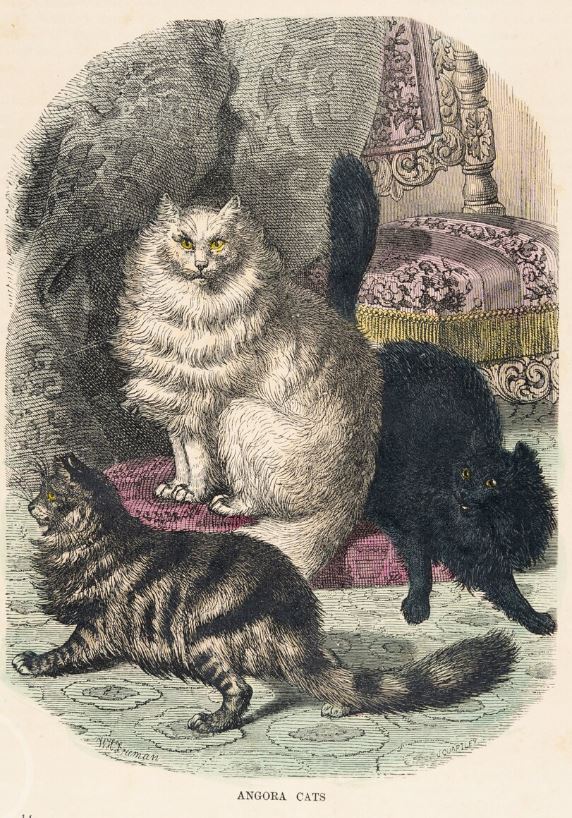

According to the newspaper, there were more mangy cats on the Bowery than in any other part of the city. Apparently, the reporter had not heard about the black Angora and white Persian cats who made their home at the Capitol Hotel on the Bowery.

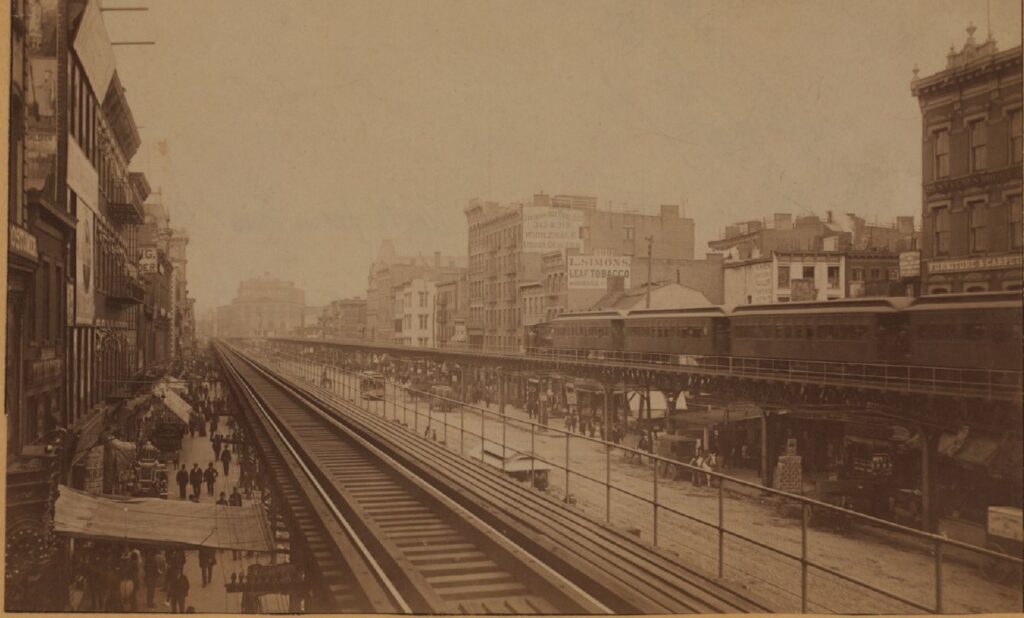

The Capitol Hotel occupied the top three floors of what was now a five-story brick building at 286 Bowery. The hotel had opened in 1897 under the proprietorship of a retired NYPD police captain named William Straus. On the bottom floor was a saloon, and a pool room (not completely legal) occupied the second floor. As police headquarters was only a few blocks away on Mulberry Street, many if not most of the patrons were police officers.

Sometime around 1899, Straus received a black Angora cat to serve as mascot of the hotel and saloon. Straus gave it a derogatory name, so for the purpose of this story I’ll call him Blackie.

Straus thought Blackie might like a girlfriend, so he adopted a white Persian whom he named Tabby. Blackie and Tabby became the best of friends. They were inseparable, and even shared milk and food bowls in the saloon. (The press never reported on how many kittens the couple produced.)

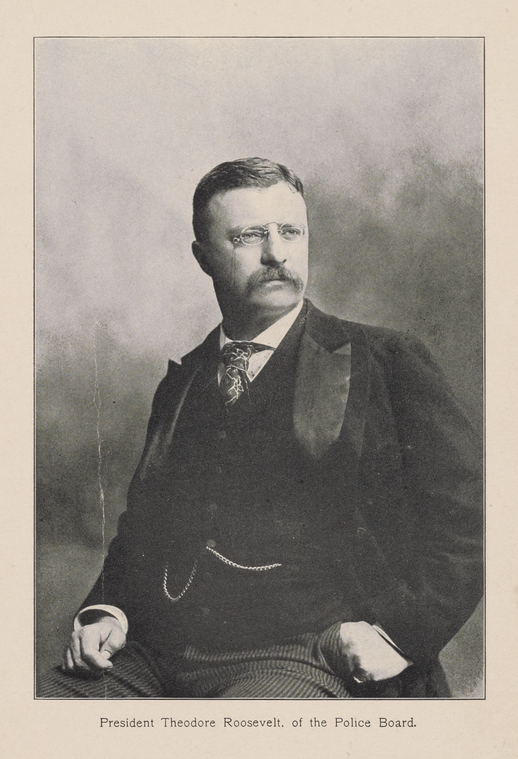

One of Blackie’s other good friends was Teddy Roosevelt. Yes, that Teddy Roosevelt.

When Roosevelt was carrying a big stick as the city’s police commissioner, he would often eat at Michael F. Lyons’ restaurant at 259 Bowery (his favorite dish was a slice of roast beef with vegetables, pie, and a mug of ale). Blackie would saunter out of the Capitol and schmooze with Roosevelt on the street as the future president was making his way to the restaurant.

As chief mouser of the Capitol saloon and hotel, Blackie earned himself the acclaimed reputation as the best ratter of the Bowery. He could charm vermin out of their hidey holes as good as the Pied Piper, collecting a slice of liverwurst or bologna followed by a shot of milk for every rat slaughtered.

In 1904, Straus sold the business to Patrick (or possibly Charlie) Muller. Muller insisted that the two cats be included in the deal–he would not purchase the business unless the cats were included. For the next three years, life went on as usual for the popular feline mascots.

One night in 1907, Muller made the big amateur mistake of letting the night clerk bring another cat into the building. He named the cat Malta.

Tabby was enamored with this new feline beau, and she did everything she could to win the affections of the new cat. Of course, this made Blackie very depressed. With his friend Teddy now in the White House, Blackie probably felt that he had lost his two best pals.

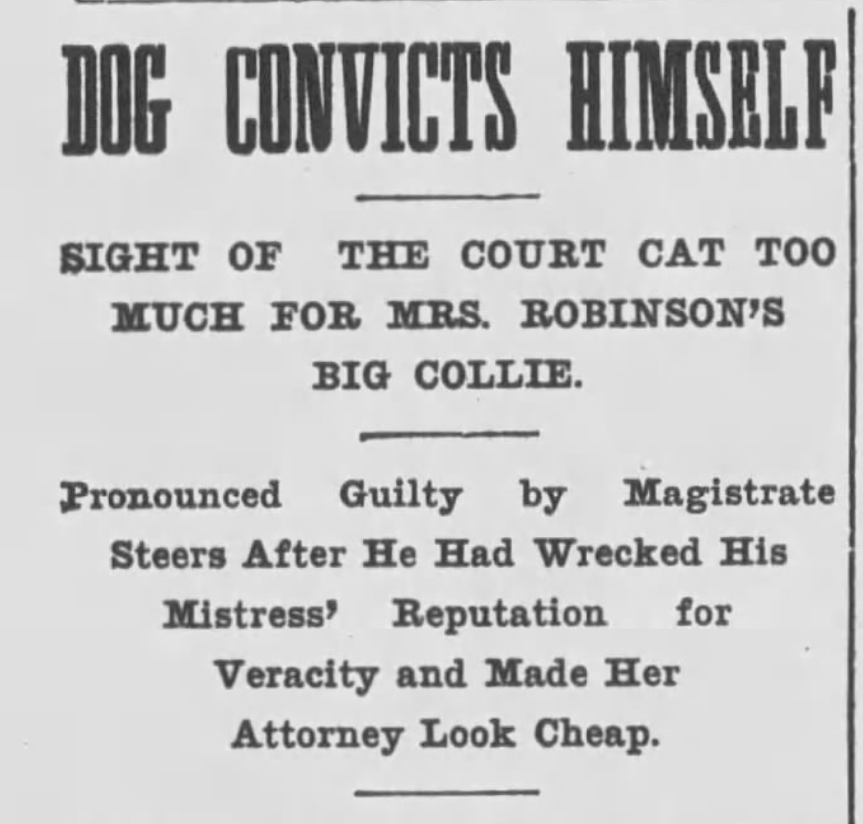

The reports of Blackie’s death greatly differ. One newspaper said he committed suicide, but the Capitol’s bartender told the New York Evening Sun that Blackie had too much common sense to take his own life.

According to one report, in November 1907, Blackie caught Tabby and Malta sharing the milk bowl together in the dining room. He went upstairs to the third floor and perched in the open window until the elevated train approached.

When the City Hall train arrived, he leaped directly in its path and was killed instantly. His body fell onto the Bowery, where a crowd of people witnessed the horrific event. Several men who knew the cat ran into the Capitol to let Muller know that his beloved mascot had died.

However, according to bartender George Washington Watts, it was not jealousy that led Blackie to climb out onto the fire escape and jump onto the train tracks. He said he did not know why the cat did this, but he knew it was not due to jealousy over Malta. “It don’t seem like the same place with [Blackie] gone,” Watts said. “The Bowery will never see his equal again.”

Whether it was by accident or suicide, Muller said he was planning on giving the cat an elaborate funeral; Tabby and her new lover were reportedly evicted from the hotel.

The End of 286 Bowery

In 1929, 286 Bowery and the two adjacent buildings were sold to New York City as part of the city’s Houston Street subway project.

In order to construct the Sixth Avenue subway, the narrow Houston Street was dramatically widened from Sixth Avenue to Essex Street. The street widening involved demolition of buildings on both sides of Houston Street, including 286 Bowery, which resulted in numerous vacant small lots and ugly, windowless bare walls.

Although some of these lots have been redeveloped, many of them are now used by vendors, community gardens, playgrounds, and art murals. And yes, we have now come full circle.