In Old New York, canine mascots were forbidden in all the social clubs. Cats were not. Thus, clubs like The Lambs Club, the Lotus Club, and the New York Yacht Club had one or more feline mascots.

The following tale is about three of the many cat mascots of the New York Yacht Club.

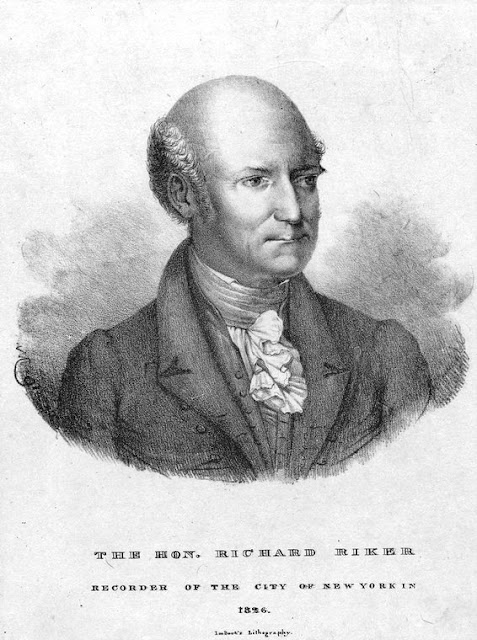

The New York Yacht Club was founded on July 30, 1844, when John Cox Stevens invited eight of his friends–including John Clarkson Jay, George L. Schuyler, and Hamilton Wilkes–to join him on his yacht, Gimcrack, in the New York Harbor.

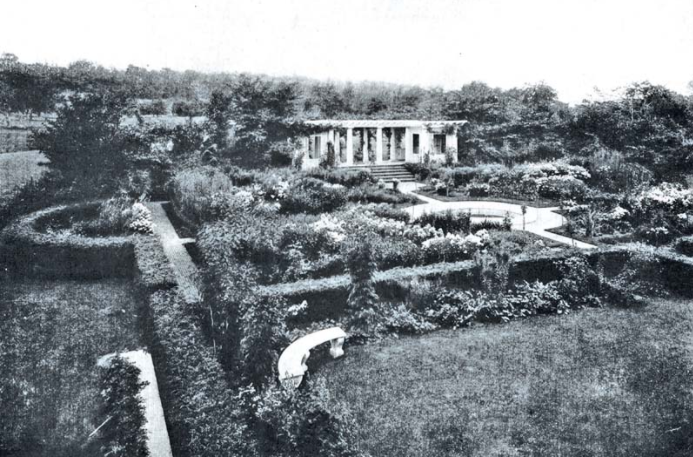

The club’s first clubhouse was established at Elysian Fields, in Hoboken, New Jersey, on land donated by Commodore Stevens (now the site of the Stevens Institute of Technology). Over the years, the club moved to several other locations, including Staten Island, Glen Cove, and Mystic, Connecticut.

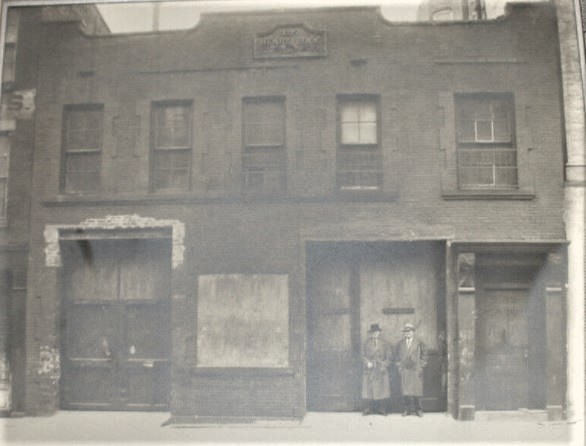

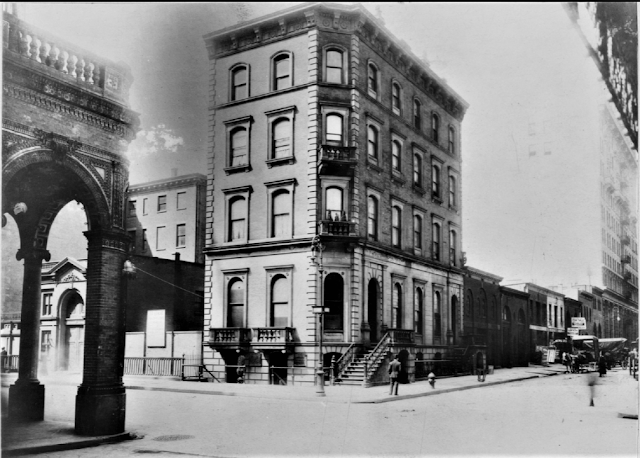

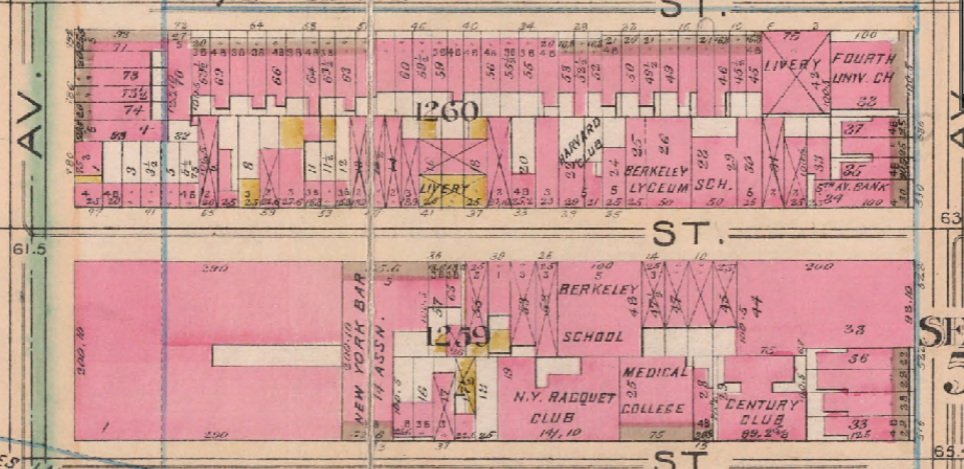

In 1872, the New York Yacht Club took over three rooms on the second floor of the American Jockey Club headquarters. This four-story brick and stone building was constructed in 1867 on the southwest corner of Madison Avenue and 27th Street for Leonard Jerome, August Belmont, and other founding members of the American Jockey Club who raced their horses at the Jerome Park Racetrack.

According to Wood’s Illustrated Hand-Book to New York (1873), “These rooms are beautifully fitted up, and contain a perfect museum of nautical curiosities, comprising some handsome pictures, and a complete set of models of all the yachts that have belonged to the club.” There was a reading room overlooking Madison Avenue that featured reading materials and more than 120 yacht models, a second room furnished with sofas and writing tables, and a bar in the third room.

Sam the Mascot Cat

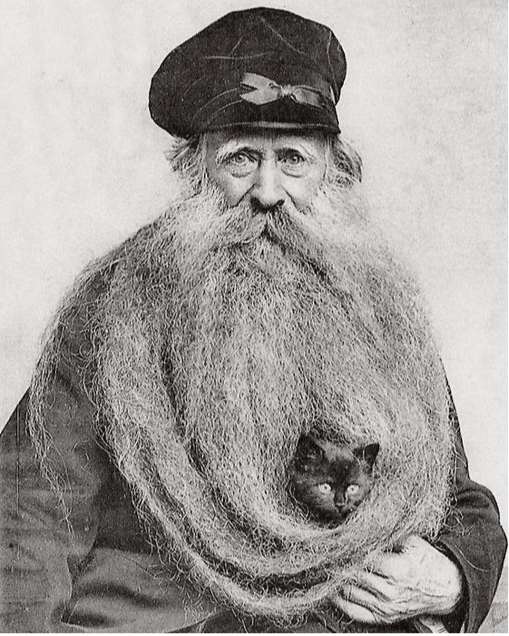

Sometime around 1883, a young, all-black kitten bypassed the Jockey Club on the first floor and wandered into the second-floor rooms of the New York Yacht Club (perhaps he could smell the of odors of fish lingering in the members’ clothes and hair).

As The New York Times noted a few years later, “In accordance with a popular superstition his advent under the circumstances was considered ‘good luck,’ and he was consequently made quite at home, and he remained there. Sam soon became a general pet of the habitués, and never sought fresh pastures excepting, indeed, for a nocturnal gambol on the roof once in a while.”

Sam was a well-fed feline, but he earned his keep by being “an industrious ratter” and keeping “the building free from the ravages of the destructive rodent.” Although Sam enjoyed partaking in the neighborhood backyard concerts for felines, he never once hosted a concert on the clubhouse premises. Most important, he never allowed any four-legged intruders into the club.

Sam was very sociable and friendly with each member of club. He would welcome them by by “gracefully passing around their legs or sitting under their chairs.” He would sit up all night with the old salts, refusing to sleep until the last of the members had left, no matter how late.

In 1884, the New York Yacht Club moved into its own quarters one block north in a three-story townhouse at 67 Madison Avenue. Along with the yacht paintings, models, and reading materials, the members took along Sam the cat to their new, more modest home.

Relocating Sam was no easy task, even though he only had to travel one block. The poor cat had to be trapped and placed in a bag.

Like most cats, Sam was traumatized in his new surroundings at first, and made a quick escape back to the old clubhouse. Fortunately, “not finding his household gods there, [he] meekly returned to the place, and soon made himself at home.”

Two years later, on June 6, 1886, The New York Times reported that the members of the New York Yacht Club were mourning the loss of their well known and esteemed black cat mascot. According to the newspaper, the members were heartsick when club member Niels Olsen found Sam dead in his tiny bed.

Dobbins the Manx Mascot Cat

Six years after the passing of Sam, another kitten arrived at the New York Yacht Club headquarters on Madison Avenue. She was a quiet cat that didn’t attract much attention, but she could jump like a rabbit.

In 1893, the members of the club named her Tobbins, after Tobin bronze, a type of expensive metal plating that covered the bottom of a victorious yacht called Vigilant. They soon changed her name to Dobbins, perhaps because it’s a bit easier to pronounce.

Dobbins had full run of the clubhouse, which explains why she was constantly caressed by the members whenever she was nearby. She became so famous that yachtsmen from all over the country would call at the New York Yacht Club just to visit their cat. (The only visitor she didn’t like was the Irish Earl of Dunraven, who had tried to argue that an Irish yacht had beaten an American yacht.)

On January 5, 1897, Dobbins was seen sitting on the front stoop of the clubhouse with a big Maltese (gray) Tom cat. It was raining heavily, but the two cats seemed perfectly content with each other’s company. It was the last time the members saw their cat alive.

Sometime after midnight, a policeman saw a dead cat in front of 69 Madison Avenue and recognized it as Dobbins. He made a note of the location so that he could report that a dead cat was on his post (reporting all dead animals was part of police officers’ duties back then.) When he returned to the site about a half hour later, the large gray cat was standing guard over Dobbins.

The policeman tried to get the cat to move, but the gray cat glared at him and arched his back in defense. The cat began to howl in anguish, only stopping from time to time to lick Dobbins’ lifeless body.

An hour later, the policemen came back to the scene after still hearing the crying cat. As The Sun reported on January 8, the cries were “more mournful than the policemen had ever heard before.” Touched by the cat’s mourning, he stood and watched the cats for several minutes without disturbing the male cat.

When Niels Olsen (then the club’s superintendent) learned of Dobbins’ death, he examined the cat’s body. He told reporters that there appeared to be a deep ridge across the neck, as if she had been run over or kicked. He contacted the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and placed a sign in the clubhouse that read: We Mourn Our Loss. Dobbins. Died Jan. 6, 1897.

All day long on that Tuesday, the male cat continued guarding the body of Dobbins. Several dogs sent him scurrying for shelter inside the iron railing, but he refused to eat or leave the area until the following afternoon, when the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals removed poor Dobbins.

Although the Tom cat did not try to stop the men from taking Dobbins away, he did watch the wagon intently as it started down the street. He followed the wagon for half a block, took one more look at it, and disappeared around the corner of 27th Street, heading toward Fourth Avenue.

According to The Sun, no one knew who owned the Tom cat, but he frequently came calling for Dobbins, and she always answered his call. Perhaps he is the reason she had so many kittens, many of which were adopted by club members over the years. (In 1893 she gave birth to 18 kittens; 10 in 1894; 8 in 1895; and 9 in 1896. She was pregnant at the time of her death.)

Captain, the Son of Dobbins

Following Dobbins’ passing, the members adorned her kitten Captain in black mourning crape. The one-year-old kitten would take his mother’s place as the club’s mascot cat.

The club men told The Sun reporter that they wished they had captured the guardian Tom cat before he disappeared down the street. They said they would have welcomed him into the clubhouse as another daily reminder of their beloved Dobbins.

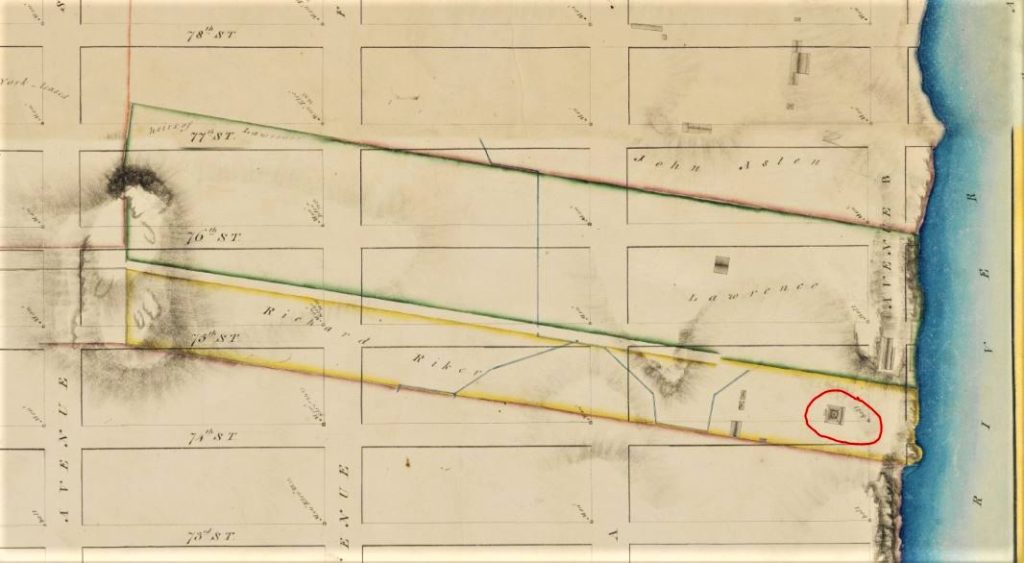

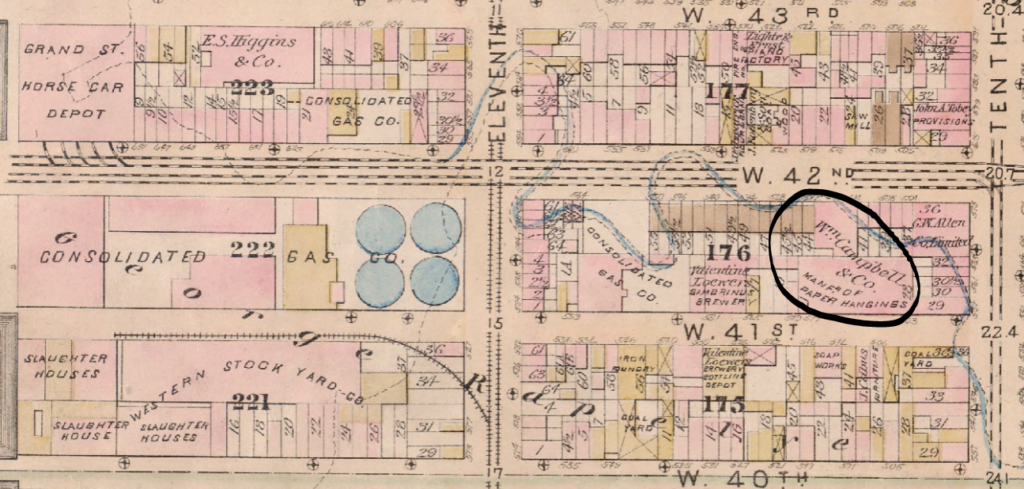

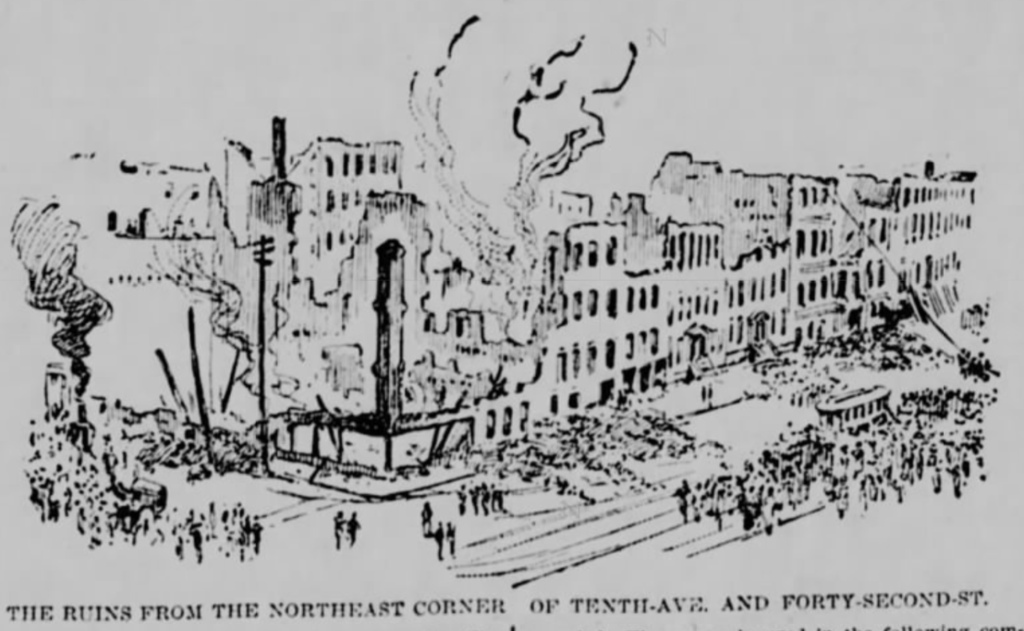

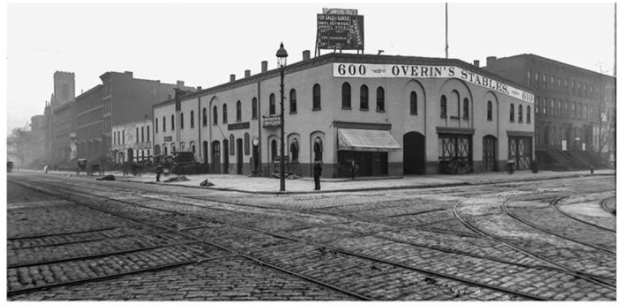

Right around the time of Dobbins’ death, New York Yacht Club Commodore J. Pierpont Morgan began looking for a new location for the club. In October 1898, he announced that he would donate three lots on West 44th Street between 5th and 6th Avenues (then a block of horse stables) for the new building. In return, he would be allowed to select the winning design.

Morgan stipulated that the new clubhouse must have a model room adequate to exhibit their extensive collection as well as serve as a meeting room for 300 people. He also called for a library that could accommodate 15,000 books, a chart room where members could map out their cruises, and 20 sleeping apartments.

The result was a circa 1901 clubhouse designed by Whitney Warren in the Beaux-Arts style. Hopefully, the club members brought Captain or any other mascot cats to their new home (and let’s hope the cat had a more dignified trip uptown on this move than poor Sam had inside a bag!).

In 1908, retiring Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt gifted the Yacht Club with a $100,000, three-story stable adjoining the clubhouse at 35 West 44th Street. The club converted the old stables into an annex to accommodate its growing membership.

The annex was eventually sold to the Harvard Club of New York City in 1930, and is still occupied by that organization today. The New York Yacht Club is still next door in its 1901 clubhouse.