Cats in the Mews: May 14, 1892

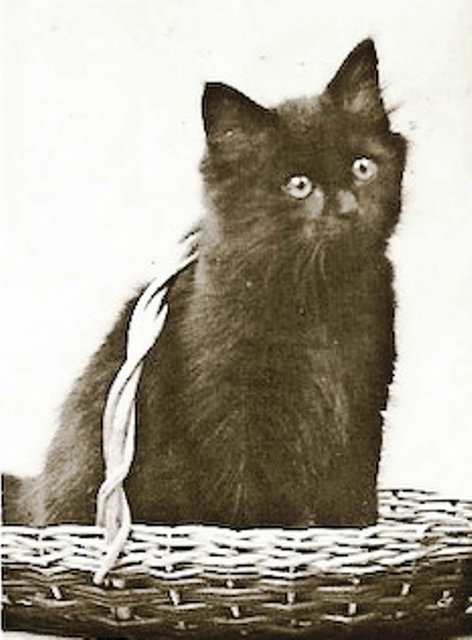

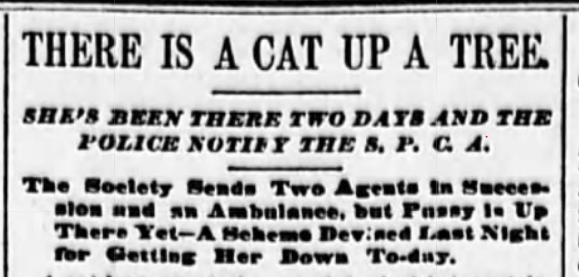

On May 14, 1892, The New York Sun reported a cat stuck in a tree in the yard of Mrs. King’s three-story brick row house at 227 West 11th Street. According to the newspaper, the black-and-white cat had entered a boarding house at 226 West 11th Street and insisted on occupying some of the residents’ chairs. A dog named Carmencita chased the cat from the house and into the street, where another dog and a boy joined in the chase.

The cat escaped up a large walnut street that shaded Mrs. King’s yard.

Cat vs Clothes Pole

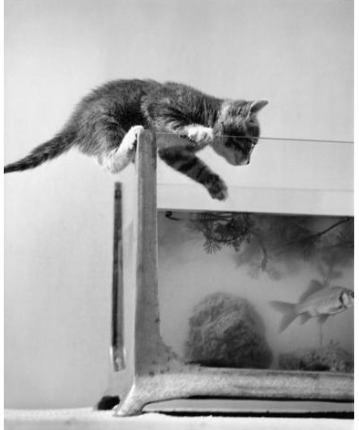

The cat made her way to a branch that was level with the third floor of Mrs. King’s house. For two days, she refused to budge. Mrs. King tried coaxing the cat with a long clothes pole that she stuck out her small window, and several neighbors tried to climb the tree, but the cat didn’t make a move. She just sunk deeper into a hollow in the tree trunk.

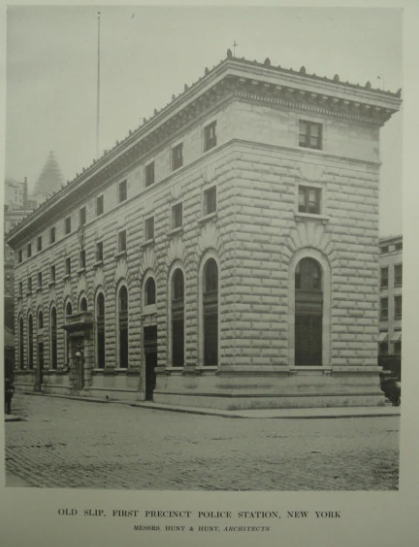

Finally, Roundsman Eugene D. Collins of the Charles Street police station (then located at 94 Charles Street) came along and saw some children looking up at the tree. He contacted the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

SPCA Superintendent Charles H. Hankinson sent an agent to the scene. The agent tried to find the cat, but when he didn’t see her, he just left.

The next night, upon notification that the cat was still stuck, SPCA Agent Daniel Seymour went to investigate further. By the light of the electric lamps on West 11th Street, Agent Seymour could see the poor kitty. He could also hear her cries for help.

Mrs. King told him that she was able to feed the cat by tying two clothes poles together and putting a piece of boiled meat on one end; the cat seized the meat and ate it. Although the woman left the pole between the tree and the window, the cat refused to cross it.

Stay with me, it gets better.

Agent Seymour thought he could get a long, wide plank (at least 20 feet in order to reach the window from the tree) and use that to lure the cat indoors. However, the only window wide enough to accommodate the plank was occupied by a boarder who had tonsillitis. Seymour told Mrs. King that the SPCA would move her boarder to another room and build a bridge for the cat.

On May 14, a parade of SPCA agents, police officers (including a police van) and three news reporters made their way to the walnut tree on West 11th Street. According to the New York World newspaper, the policeman formed a cordon around the tree to keep spectators away.

Agent Seymour than went into the now unoccupied room in Mrs. King’s house and placed a piece of fish on the plank. Cautiously, he pushed the plank toward the tree branch where the cat was crouching.

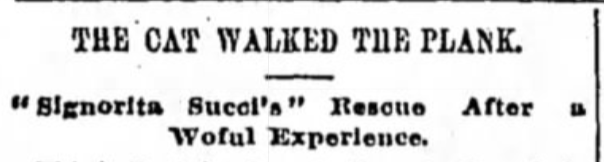

No sooner did the cat see the fish than she literally walked the plank. As soon as she grabbed for the fish, Agent Seymour carefully pulled the plank inside with the cat on it and, as The World noted, ” thus added another laurel to the refulgent wreath which adorns the rooms of the SPCA.”

Following the ordeal, a clergyman from Dr. B.F. De Costa’s church (Church of St. John the Evangelist) on the corner of Waverly Place and West 11th Street christened the cat Signorita Succi “for obvious reasons.” (Succi, being the plural of succus, which is an expressed fruit or juice.)

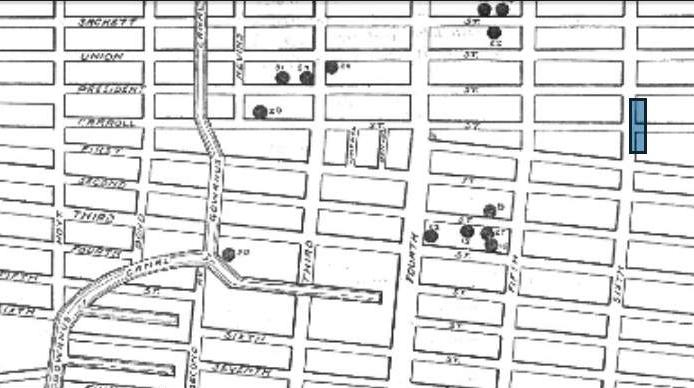

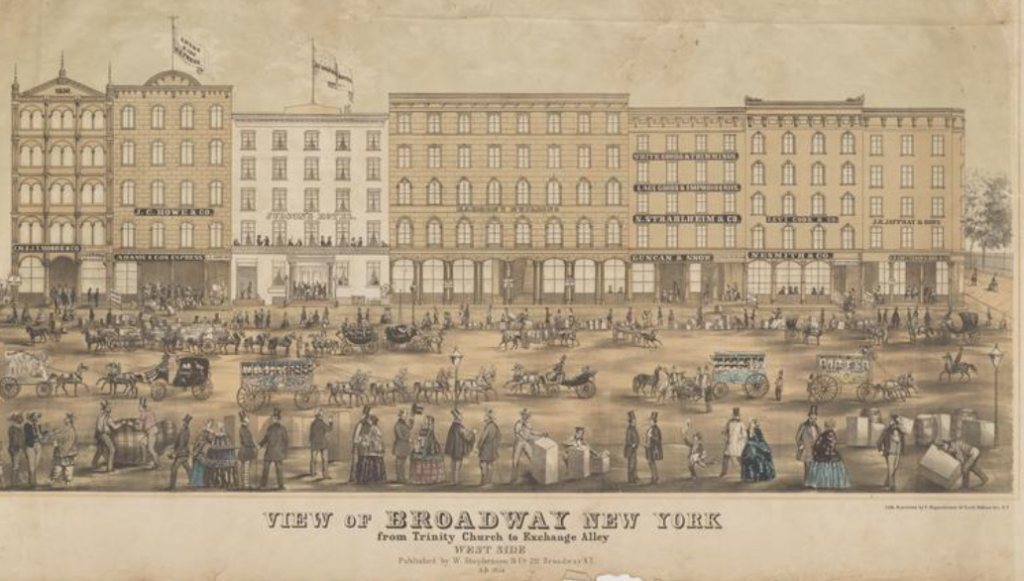

Sir Peter Warren

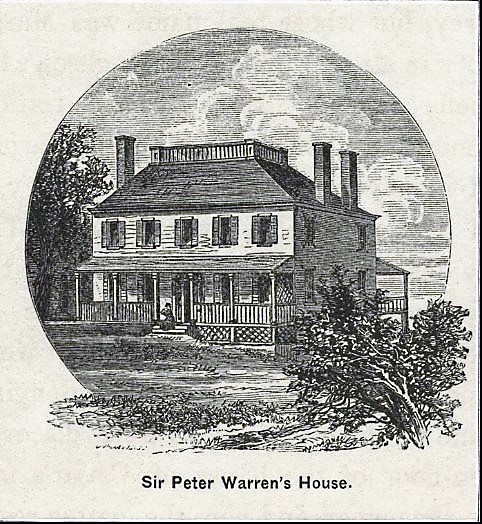

The land upon which this cat-up-a-tree incident occurred was once part of a large 300-acre farm along the Hudson River waterfront owned by Sir Peter Warren, a Royal Navy officer of Irish descent. The Warren Farm stretched from the Hudson River to the Bowery and from Charles to West 21st Streets.

Warren acquired the five distinct parcels of land comprising the large farm between 1731 (the year he married Susannah De Lancey) and 1744.

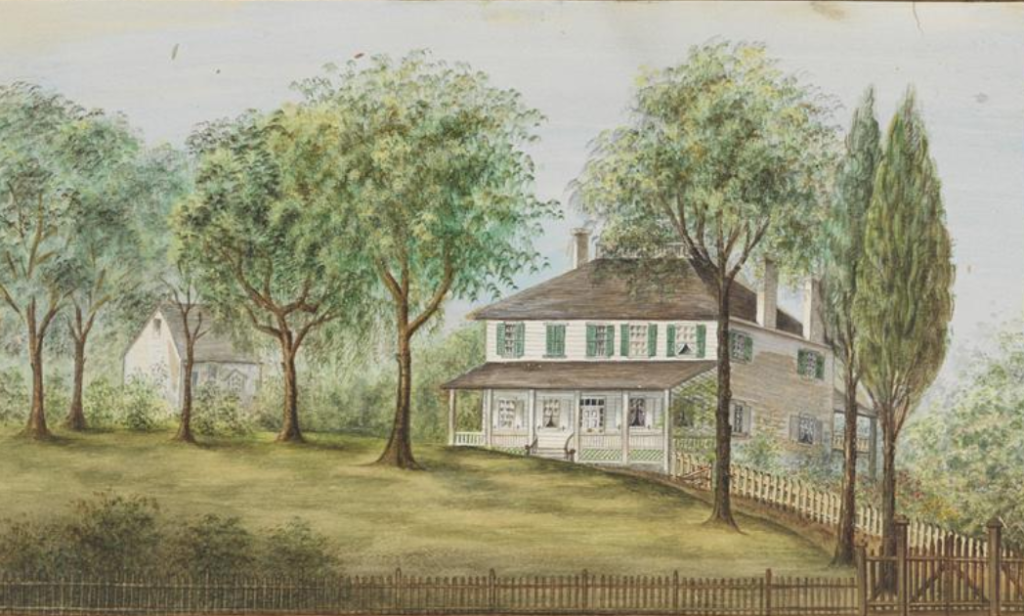

In the early 1740s, Warren moved into a stately home overlooking the river on the block of land bounded by today’s Bleecker, Charles, Perry, and West 4th Streets. The house had been constructed around 1726 for James Henderson, its first occupant.

Here is how the Greenwich Village Historic District described the home:

“[T]he Van Nest mansion resembled ‘Hamilton Grange.’ It was a rectangular, two-story clapboard house, five windows wide, and at each side there were two tall chimneys flanked by windows. Covered porches extended along both front and rear and were connected by a central hall. The paneled front door, crowned by a transom of simple glass panes, was reached by four steps from the drive, which led to the avenue of buttonwood trees extending to the Hudson River.

The rear porch, approached by a flight of fourteen steps, overlooked the terraced flower garden that stretched across the block. The house, near Charles Street, was set in the midst of shade trees. Entered from Perry Street was the two-story brick stable and carriage house. Fruit trees, a large vegetable garden, a cow and a picket fence surrounding the block completed the picture of the attractive Van Nest home, which was finally razed in 1865, giving way to the solid block of City residences we see today.”

Following his death in 1752, Peter Warren’s estate was divided among three of his daughters; the land was further divided into lots and sold in the 1830s. Jeremiah Pangburn, a real estate developer and mortgage broker, was the chief developer of this land (his home, which is still standing, was at 78 Perry Street).

The last person to occupy Warren’s mansion was Abraham Van Nest, a prominent New York City merchant who purchased the land in 1821. The home was demolished in 1865, one year after Van Nest passed away.

227 West 11th Street

Although Mrs. King’s row house at 227 West 11th Street was demolished in the early 1900s, there is still a rather large tree in front of the existing building. I have no way of knowing if this is the tree that Signoria Succi got stuck in, but the next time I’m in the neighborhood, I’m going to walk by and look up at the tree just for the nostalgia.