Cats in the Mews: February 20, 1942

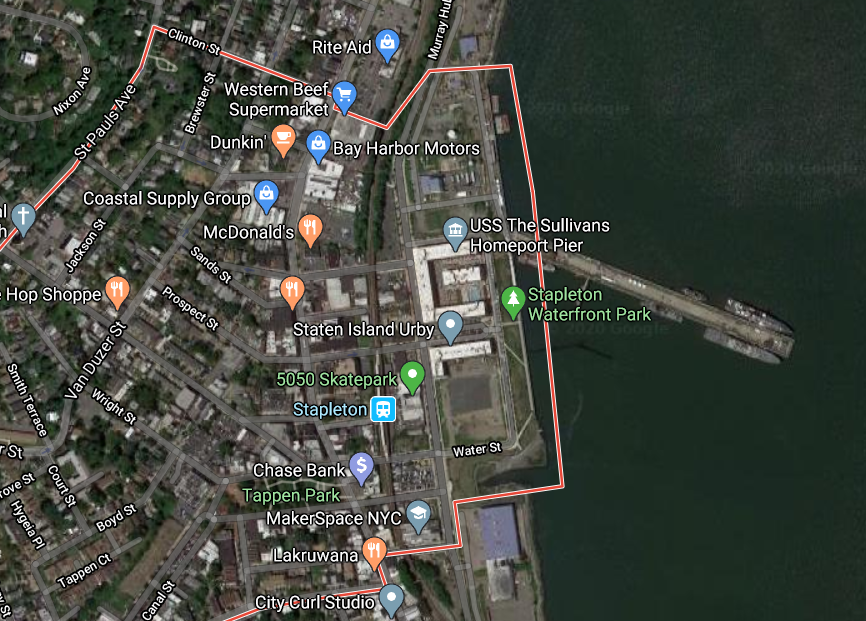

This is about a refugee ship, 396 refugees from Lisbon. It’s the usual stuff–a baby was born, a man died, a princess born in Flint, Michigan, escaped across Spain and a guy had to get a passport for a cat.”–Joseph Martin and Gerald Duncan, ship news reporters at Stapleton, Staten Island, New York Daily News, February 21, 1942

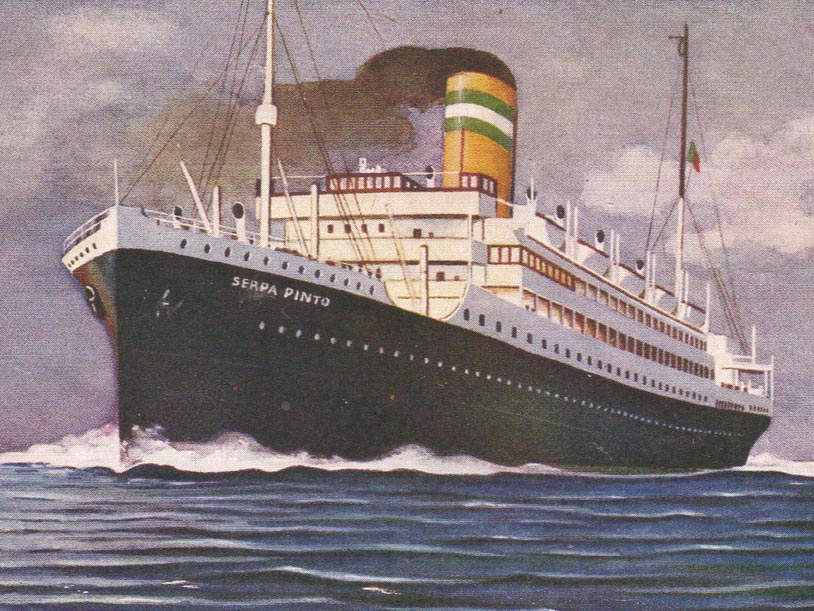

At 3:30 p.m. on February 20, 1942, the Portuguese steamship Serpa Pinto tied up at Stapleton, Staten Island, after a 27-day crossing via Casablanca, Africa, Jamaica, British West Indies, and Cuba. According to the Daily News, the crossing was smooth, with not one sighting of a war-time submarine.

One of the refugees on board the ship was a 39-year-old princess named Jane Lawrence Vatchandze. The Michigan-born princess had married Georgian Prince David Vatchnadze (Russia) a year earlier.

Prince David had been working at an auto plant in Paris when the war forced the couple to slip across the border to Spain at night in secrecy. The prince and princess were separated at Havana because of a visa issue.

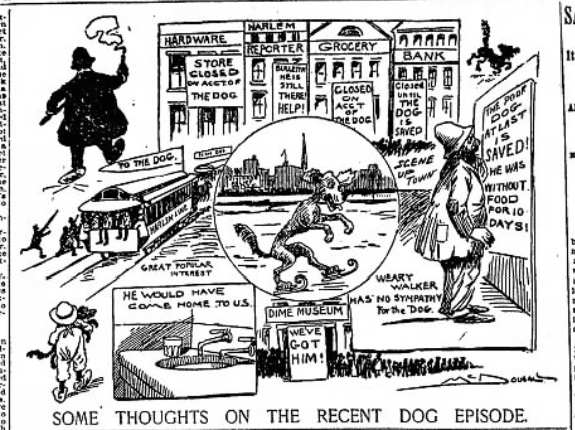

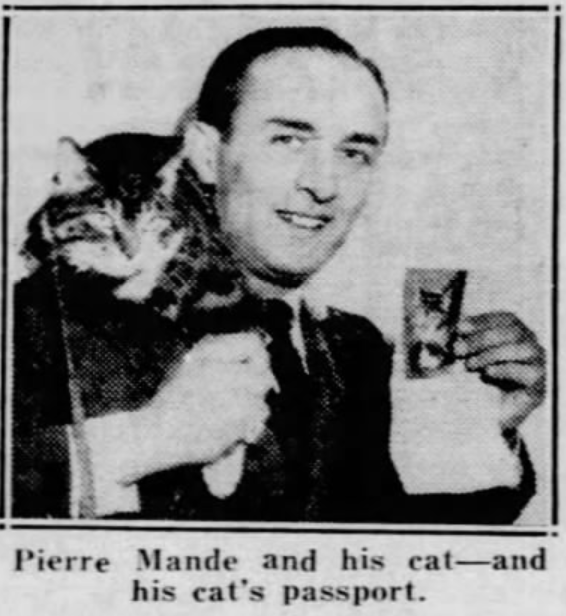

Another passenger was “Pierre Mande,” who was traveling with his cat, whom he called John Pierre Chates (probably should be Jean Pierre Le Chat). This story seems a bit more far-fetched than the princess story, but as one of the ship reporters literally said, “This thing about the cat and the passport smells a little like a publicity stunt, but what the hell.”

According to Pierre, he had been an orchestra leader on several of the large French liners, including the De Grasse and the Paris. He also appeared at the Ritz in Paris before the Germans came in and occupied the city.

In September 1939, Pierre joined the French army. He took part in the attack on Karlsbrunn, Germany, and was captured. Somehow he managed to escape back to Paris, where his cat was still living. The cat had been a gift from a local baker, and Pierre was quite fond of him.

The reporter continued, “He took the cat and escaped to Nice concealed in the bottom of a vinegar wagon. Finally he got to Lisbon and he had to pay 100 francs for a passport for the cat and 50 francs for a visa. That’s what he said. It’s not much of a cat, tiger-striped like any alley cat, but he said it meows the scale when he plays his fiddle.”

The Serpa Pinto and the European Refugees

The refugees were brought to New York by the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), which had by that time helped financed the crossings for 2,200 people leaving stricken Europe following the attack at Pearl Harbor. (First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt became very active with the JDC in 1940 because of her moral conviction that the refugees were not undesirables–as the US State Department had once labeled them–but rather were future patriotic Americans.)

Many of these refugees had made their way to Portugal, which, as a neutral country, had become an unexpected portal to freedom for tens of thousands of Jewish and non-Jewish refugees.

Some well-to-do refugees who made it to Lisbon via the Franco-Spanish border could afford expensive seats aboard Clippers, aka the “flying ships” of Pan American Airways, which made Atlantic crossings twice a week. But the majority of refugees had only one option: to obtain visas and secure passage on board one of the Portuguese liners continuously crossing the Atlantic to destinations including Havana, Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, and Rio de Janeiro. The SS Serpa Pinto became the leading bearer of refugees across the Atlantic.

The JDC maintains a database of passenger lists for the Serpa Pinto journeys between 1941 and 1944. I found the manifest for the January 24, 1942 sailing, which does not list Pierre Mande or his cat. However, I found a third-class passenger named Samuel Mandelbaum from France; the passenger was listed as a 39-year-old musician, which seems to be a good match with Pierre Mande, the orchestra leader.

America’s First Free Port at Stapleton, Staten Island

The municipal piers at Stapleton were built between 1920 and 1920 under the administration of John Francis Hylan. At the time, the project was called “Hylan’s Folly” because the piers were never fully used, and thus, never profitable.

In 1937, Stapleton opened as a free port (Foreign Trade Zone No. 1) under the Foreign Trade-Zones Act (aka Celler Act) of 1934. This act, approved by Franklin D. Roosevelt in June 1934, allowed foreign and domestic merchandise to be brought into the zones without being subject to the customs laws. It was viewed by some as a vital stepping stone to U.S. world trade advances.

The 92-acre fenced-in port at Statelton comprised Piers 12-16, including steamship piers for docking, loading, and unloading ships, as well as warehouses and sheds for packing, inspections, and storage.

During wartime the free trade zone was a lifesaver for the refugees, who were able to store their possessions and then ship them to wherever they finally settled without having to go through customs red tape.

From 1942 to 1945, in addition to serving as a port of entry for refugees, the piers were also utilized as the Staten Island Terminal facility of the Army’s New York Port of Embarkation. After World War II, the piers once again became a foreign trade zone, but their use declined over time.

Most of the Stapleton piers were demolished by the 1970s. One of the last, used for fishing, was removed when the U.S. Navy proposed to build a base in Stapleton in the 1980s. This highly controversial plan never went through, and plans to build the base were canceled in 1993.

Today, the lone Stapleton pier–Homeport Pier–is the headquarters for FDNY Marine Co. 9 barracks and the fire boat “Fire Fighter II.” The site is also used as part of the annual Fleet Week in New York City.