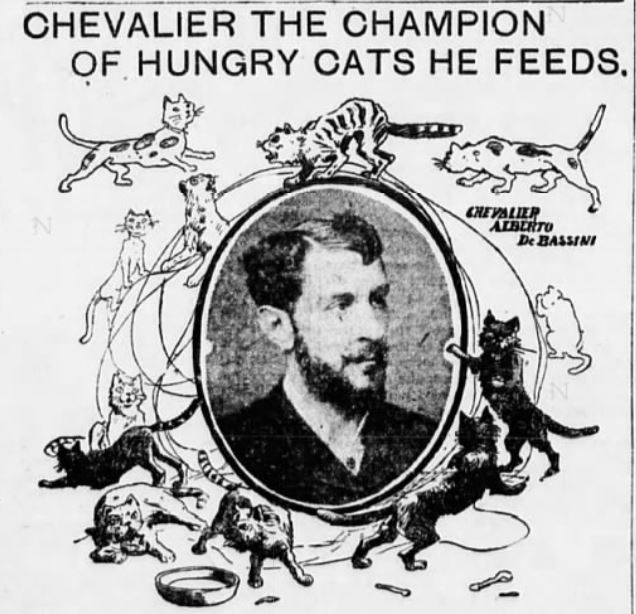

In Part I of this cat-man tale of Old New York, we met Alberto Gaston de Bassini, aka the Chevalier, a kind and generous opera singer who truly loved and cared about cats. The Chevalier rescued cats from the streets of Carnegie Hill, fed them, bathed them, sang arias to them, and named them after heroes and heroines from famous operas.

In June 1902, an inspector from the New York Health Department ordered de Bassini to remove all of the stray cats from his yard and apartment at 171 East 92st Street. One or more of the Chevalier’s Carnegie Hill neighbors had complained that the noisy clowder of more than 20 felines were making their lives miserable in the apartment building.

Alberto complied with the orders by giving away most of his cats to the many women who were seeking a musically educated cat of their very own. However, he did keep a few cats, including two kittens that were too young to be adopted and one other cat that that was too troublesome for any potential mistress to desire.

The Chevalier Continues Collecting Cats on Carnegie Hill

Being given to the artistic temperament, he has dealt unpractically in the matter of housing stray tabbies. No cat ever saw the kindly face of the old tenor, now a teacher, that it did not purr pleadingly at his heels and receive a welcome. In the neighborhood the chevalier was known for his tenderness of heart and for his consideration of stray and hungry and friendless tabbies. –New York Times, October 22, 1908

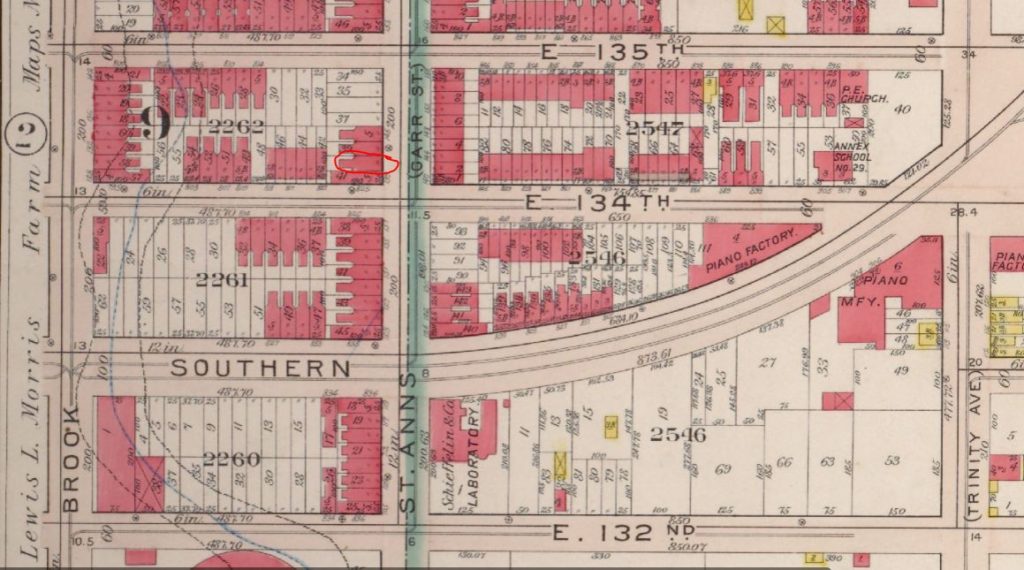

Sometime between 1902 and 1908, de Bassini moved his family to a new flat in the Carnegie Hill neighborhood at 111 East 96th Street. I’m not sure if he brought cats with him, or if he started collecting new tabbies once he moved, but by 1908 he had 28 cats. According to the New York Times, that was about 27 more cats than he could take care of at that time.

One of the cats was a tiny black kitten that the Chevalier had rescued from a barbershop on Lexington Avenue near 96th Street, about a block from his home. The barbershop was run by Tony Savareto, aka the Yorkville Barber, and his apprentice, Club-Foot Frank.

According to a small article in The Sun, Frank was sweeping the floor when he noticed a tiny black kitten caught up in the tufts of cut hair from a man’s beard. The Chevalier, who had just stepped into the shop, scooped up the kitten and took him home.

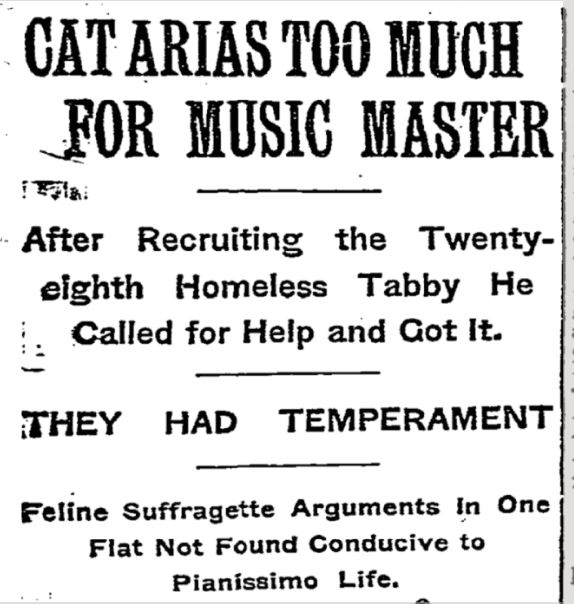

In October 1908, the Chevalier reportedly brought the 28th cat to his apartment in the small, three-story with basement brick and brownstone building on East 96th Street. It was this cat, a reporter for the New York Times said, who was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back. Here’s what the Times reported:

Yesterday the chevalier took in his twenty-eighth cat and found that there was barely room for his most promising pupil. The young lady was prepared to sing Azucena’s ‘Stride la Vampa,’ and was primed and ready for it when the twenty-eighth cat began a suffragette argument with the other twenty-seven, and the music lesson began with an obbligato that would have given ideas in cacophony to Richard Strauss.

‘Mater beatissima!’ moaned the chevalier. ‘It is time to get rid of a few cats.'”

According to the story, a friend of the Chevalier went to a telephone and informed the newspapers that de Bassini would be giving many cats away that afternoon from 2 to 4 p.m. The news was rushed for the early afternoon editions.

Musical Cats for Elegant Homes

Later that day, when he was finished with his music students, de Bassini sat down with a glass of wine and his smokes, and waited for the cat lovers to arrive. He told the press he would choose only those who promised to provide an elegant home for the cats; young boys and any type of shop owner–especially a butcher shop owner–would be turned away if not slapped in the face for even trying to get a cat.

The first customer to arrive was a deaf woman who said she knew all about the history of Egyptian cat worship. She said she wanted a few cats, and that she knew all about cats and their philosophy and yearnings. The woman reportedly left the flat with as many cats as she could carry.

As the New York Times noted, “The deaf woman was followed by a dozen other women with keen ears and large desires to own cats. They swamped the apartment house, all demanding cats, and all wanting to know whether it was true that the Chevalier’s tabbies had become so trained in music that they could howl in key to the music of Verdi and the other Italian masters.”

One woman told de Bassini that she was also an artist, and that she knew for certain that cats “have a musical comprehension” and an “artistic nature.” The Chevalier bowed low and presented her with a cat.

Another woman scorned those who were too snobby to take a mangy cat, noting that these cruel women didn’t love cats for themselves, but only wanted cats of a certain pedigree. She selected three beautiful cats and one mangy white cat whom she said would improve with a little kindness and some cold cream.

Later on in the day, a horde of newspaper reporters descended on de Bassini’s apartment, joining all the curious neighbors and “cat-demanding multitude.” Finding himself cornered, he fell into the arms of a reporter and begged him to end the publicity and lead him away from his almost cat-less home.

“Heaven knows when he’ll be back,” neighbor Miss Lula Baer told the press. “He is a great man and sings divinely. So do his cats. You ought to hear them. They all come in with him from the streets hungry and dirty and he feeds them and washes them, and then those cats get the artistic temperament.”

Miss Baer continued, “Oh, it’s wonderful, but it’s hard to keep as many as twenty-eight cats in a small flat, and he’s married, you know, and wants to go back to Italy soon. It would be a hard job to get a wife and twenty-eight cats to Italy.”

All in all, Alberto gave away about 17 cats and kept the rest for himself. Two of the cats he kept were Carmen, a 12-year-old, blind, jet-black cat, and Bee Ju Gee, a cat with deformed front feet.

The Chevalier of cats eventually did get back to Italy, but not before moving out of the Carnegie Hill neighborhood and living in East Harlem for a while at 1590 Lexington Avenue. By 1915, only his wife and daughter–who had a very successful career as a singer with the vaudeville circuit–were living in Manhattan. (Perhaps Alberto de Bassini chose to return to Italy with his cats rather than his wife and daughter? È possibile!)

The Chevalier passed away in Milan, Italy, at an unknown date.

A Brief History of Carnegie Hill

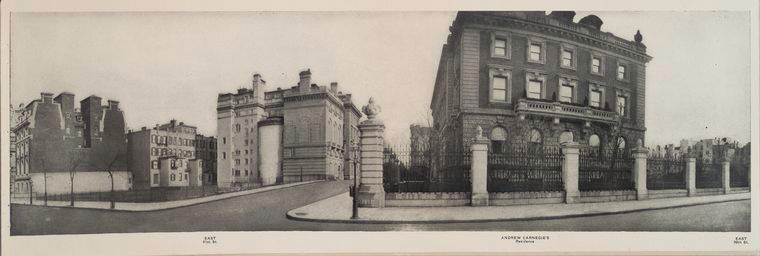

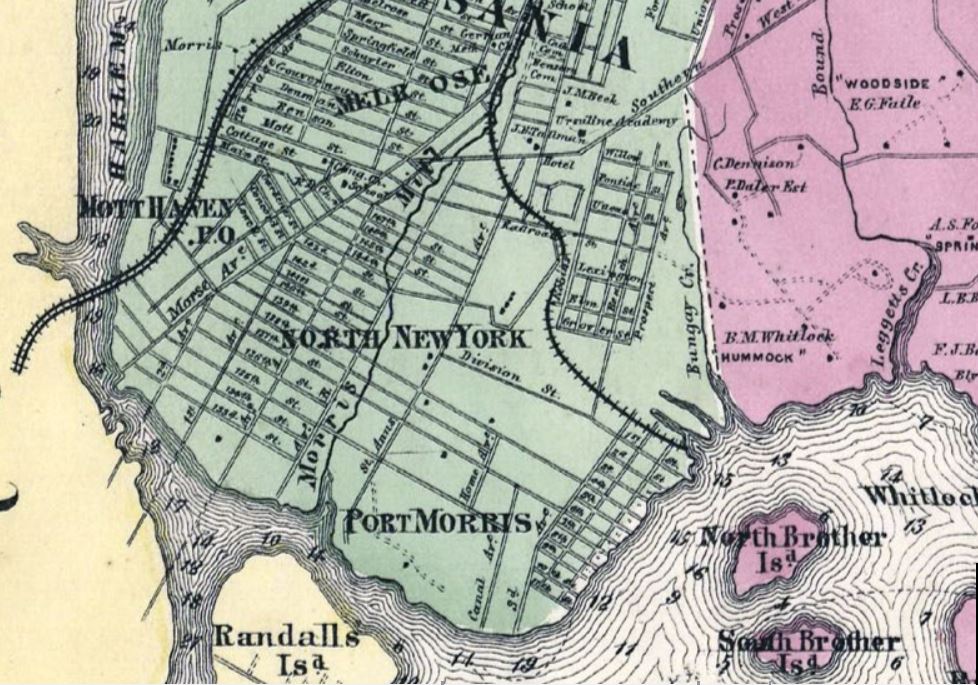

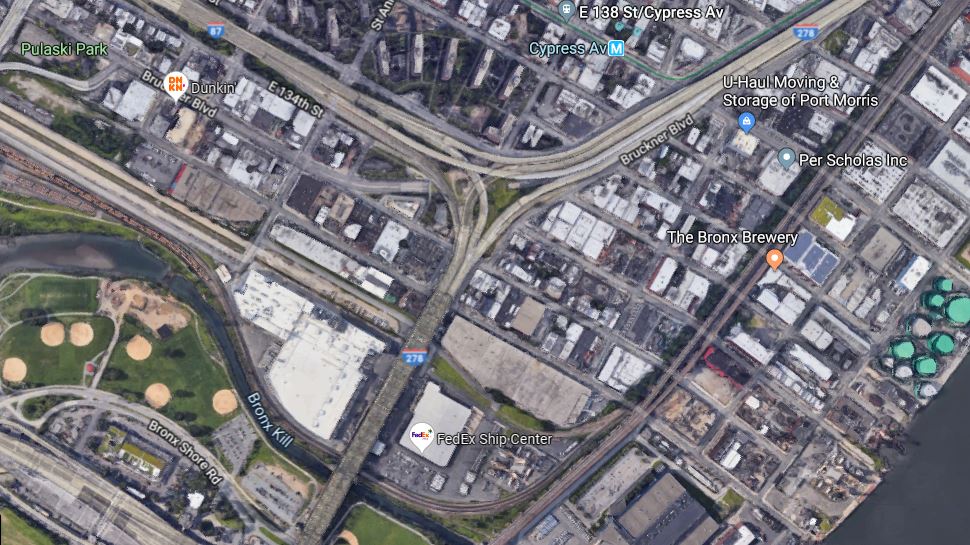

In the early 1900s, Alberto de Bassini lived with his human and feline family in the Carnegie Hill neighborhood, which is roughly bounded by East 86th to East 96th Streets between Fifth and Third Avenues.

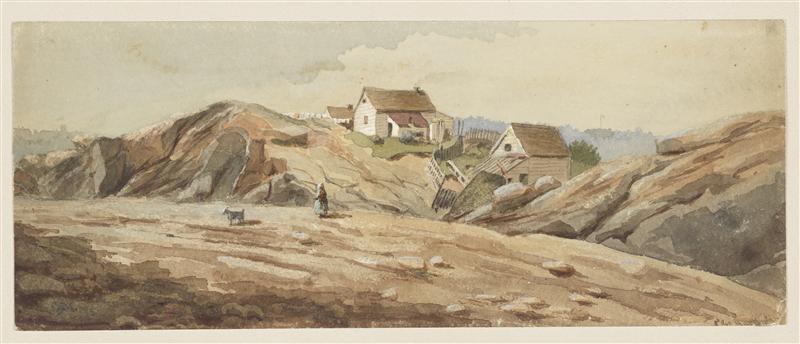

The earliest known history of this part of Manhattan goes back hundreds of years, when a tribe of the Algonquian Nation lived in a seasonal village called Konaande Kongh, which was located on a hillside stretching between present-day 93rd and 98th Streets along Park Avenue. The village was surrounded by dense woods of maple trees and berry bushes to the west and a cultivated fertile plain to the east for growing vegetables and herbs.

In October 1667, Governor Richard Nicolls granted large tracts of land in New Haerlem (which encompassed from about 74th Street to 129th Street) to Thomas Delavall, John Verveelen, Daniel Tourneur, Joost Oblinus, and Baron Resolved Waldron. The patent included all houses, buildings, barns, stables, orchards, gardens, mills, ponds, fencing, and other natural and man-made structures on the land. Resolved Waldron’s allotment was known as Hellgate or Horne’s Hook, and primarily encompassed the land from 75th to 94th Streets between Third Avenue and the East River.

Resolved Waldron’s farm, later referred to as the Waldron Farm, passed through several generations of Waldrons, including Samuel, Johannes, William, and Adolph. At one point, the farm comprised 156 acres, which included the original patent plus additional lands acquired throughout the years.

Just prior to the Revolutionary War, Adolph Waldron sold his fields and pastures to Abraham Durye, a New York merchant. Although Durye’s heirs retained a small tract near 93rd Street, most of the irregular, triangular tracts were conveyed–through the early 1800s–to John G. Bogert, Nathaniel Sandford, Xaviero Gautro, Natianiel Prime, Edward Douglas, and William Rhinelander.

The two apartment buildings where the Chevalier lived with his cats in the early 1900s were constructed on lands formerly owned by Gautro and Douglas.