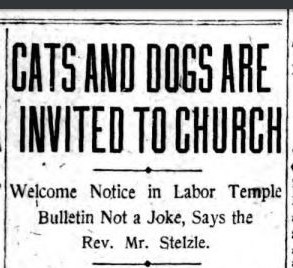

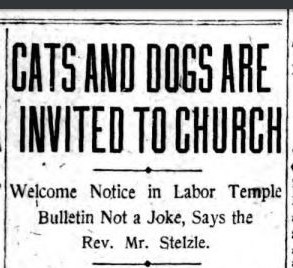

The story about the open-door policy for cats and dogs at the Presbyterian Labor Temple on Fourteenth Street and Second Avenue made the national news in 1912.

“We don’t mind a stray cat, or a dog either. If a stray dog finds a friend in the temple, we’ve brought the kingdom of God just so much nearer.” — Presbyterian Labor Temple, 1912

The above notice appeared in the weekly calendar of the Presbyterian Labor Temple, located on the corner of Second Avenue and East Fourteenth Street. People thought the notice was a joke at first, but any such idea was dispelled when a reporter talked to Rev. Charles Stelzle, superintendent of the church, at his home in Maplewood, New Jersey.

This feel-good cat-and-dog story began when a stray dog wandered into Rev. Stelzle’s church one cold winter day and snuggled up comfortably against a radiator. Rev. Steizle gave the four-legged visitor a hearty welcome and took advantage of the occasion to preach a sermon on the human treatment of animals.

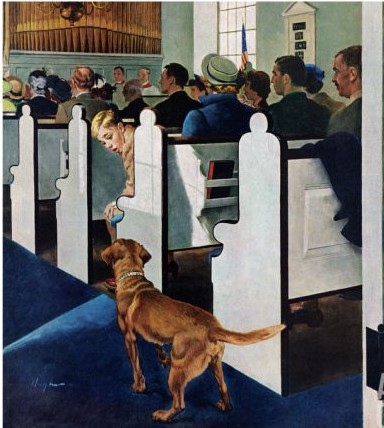

Perhaps the artist of this 1950s painting was inspired by a dog like the one who sauntered down the aisle at the Presbyterian Labor Temple.

As the Reverend Dr. Stelzle told the reporter:

“One day when I was preaching a stray dog walked right up the middle aisle. He was a medium sized, ordinary cur. Some of the congregation were distracted, so I paused long enough to welcome the dog. He walked over to the radiator in the corner and curled up, and stayed through my sermon.

“Why should I preach love and kindness and harmony, and then fail to take advantage of any opportunity to demonstrate love and kindness that presented itself? It wouldn’t be kind to chase a poor, half-frozen dog out into the street. Kindness never hurts anyone, dogs included. The more you give of it the more you have.

“Dogs and cats and snakes will all be welcome. It brings the kingdom of God nearer to earth. You can harmonize a man and a dog, a man and a cat, a man and a snake, and even a man and a woman.”

The reporter noted that he was unable to determine whether special pews would be set off for the canine and feline parishioners.

Dr. Charles Stelzle and the Presbyterian Labor Temple

Dr. Stelzle, the son of German immigrants, grew up in the slums of New York City. His father, a saloon keeper, died when Charles was only eight years old, and his mother sewed calico wrappers for a sweat shop. As one publication noted, he knew firsthand “the pangs of cold and hunger experienced behind dank city tenement walls.”

Following the death of his father, Charles went to work part-time in a tobacco sweatshop. He also hustled on the streets by selling newspapers, peddling oranges, and bussing tables at a restaurant. He quit school at the age of 11 so that he could work full time in order to help support his family.

Dr. Charles Stelzle was kind to humans and animals of all kinds.

During his childhood, Charles got in trouble more than a few times. He joined a street gang and was arrested twice. That may have been what saved him.

During this troublesome time, Charles was befriended by the minister of Hope Chapel, who took him to ball games, tutored him a few nights a week, and introduced him to the church. By the age of 21, Charles was teaching Bible school, serving as the lay elder of the chapel’s congregation, and working as a machinist apprentice for a printing press manufacturer.

After applying to several theological schools (and getting rejected for his lack of schooling), Charles was finally accepted at Dwight L. Moody’s Bible Institute of Chicago. Following his graduation, he began serving as the pastor of several urban mission churches in New York, Minneapolis, and St. Louis.

By 1906, Charles had become the Superintendent of Church and Labor, later called the Department of Social Service. He became involved in politics in 1912, working extensively for the presidential campaign of Theodore Roosevelt, and later holding a seat on the New Jersey State Assembly.

Dr. Stelzle was a firm believer that the Church could play an important role in labor disputes by acting as an impartial mediator. He challenged churches to “stay by the people and help them solve their problems.”

Churches, he explained, must not wait for people to come to them, but rather, they must go to the working people and assist them in their daily struggles. As he wrote in his biography, A Son of the Bowery: The Life Story of an East Side American, “We must talk less about building up the Church and more about building up the people.”

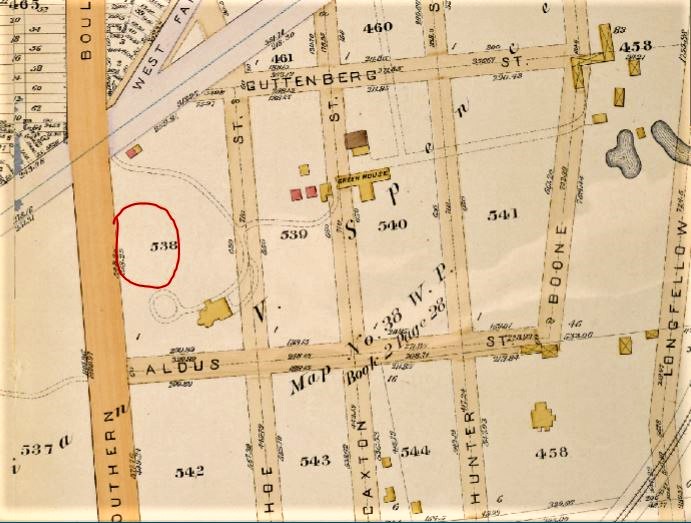

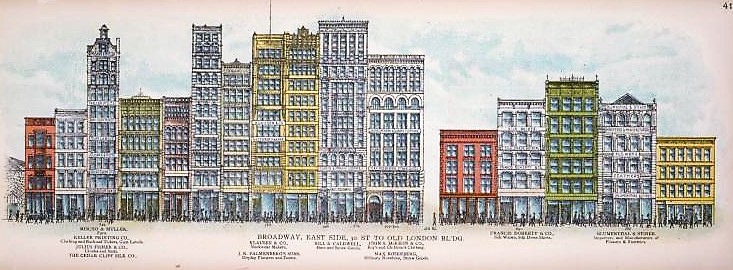

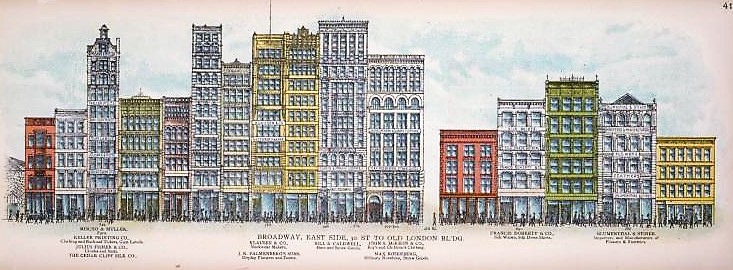

Dr. Stelzle got his start at the Hope Chapel (previously the circa 1850s Hope Baptist Church), which was located in a six-story building at 718 Broadway, between Waverly and Washington Place (the yellow building at left in this 1899 illustration). Although most of the buildings in this illustration are still standing today, 718 Broadway was demolished in the 1970s to make way for an 11-story commercial building.

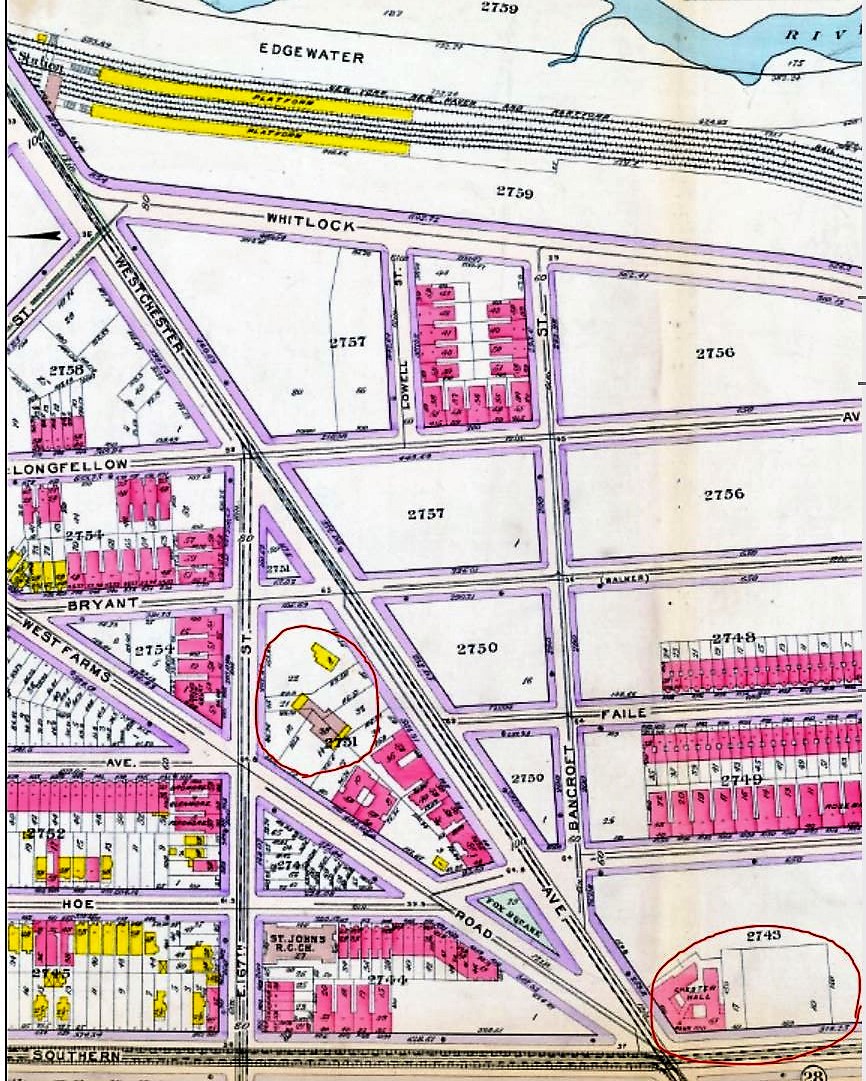

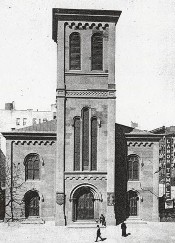

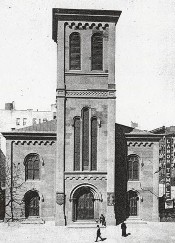

Dr. Stelzle founded the Labor Temple in 1910 as an alternative religious fellowship for working men, in which laborers and church men could find common ground and meet as equals. His plan was to utilize the empty Fourteenth Street Presbyterian Church at the corner of Fourteenth and Second Avenue (the Presbyterian Church had moved when it consolidated with another congregation on Thirteenth Street).

The Labor Temple was made possible by a fund provided through the will of John S. Kennedy (the sum of $10,000 a year for two years was taken from the fund as a rental fee). The first service took place on April 3, 1910, with George Dugan serving as the pastor.

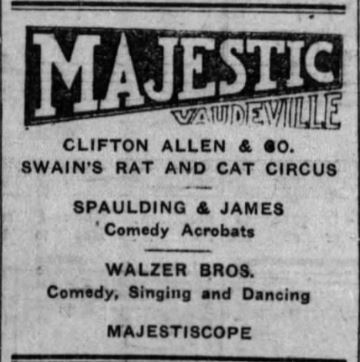

Under Dr. Stelzle’s directorship, the “church” was quite successful, and was often crowded with foreigners and native New Yorkers, all seeking a place of “clean recreation” and an alternative to the competing brothels, saloons, and vaudeville theaters. On its opening day, 500 men, including members of labor unions, socialists, anarchists, sociologists, and other persons with an interest in labor matters attended the church.

No effort was made to convert anyone (although care was taken to express the Christian viewpoint), and the good Reverend never sided with those of either fundamental or progressive beliefs. As Dr. Stelzle once said, “Both Fundamentalists and Progressives are making a distinct contribution toward the progress and development of society and my sympathies are to a certain extent with both groups.”

From 1910 to 1924, the Labor Temple Union occupied the former Fourteenth Street Presbyterian Church on the southwest corner of East Fourteenth Street and Second Avenue. It was here that a stray dog walked in and made himself at home during one of Dr. Stelzle’s sermons.

Although Dr. Stelzle preached to the working men on Sunday evenings, the mission of the church was to show congregants how to live while offering a place where “amusement of the right sort” was available to any and all. The church offered continuous services from noon until night, including music, organ recitals, moving pictures, lecture series, classes, suppers, and sermons.

As Dr. Stelzle noted in his autobiography, the Labor Temple “was a demonstration of what the Church can do in building up the whole life of the people, with special emphasis on their spiritual welfare.”

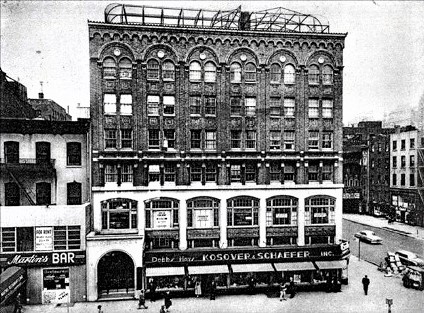

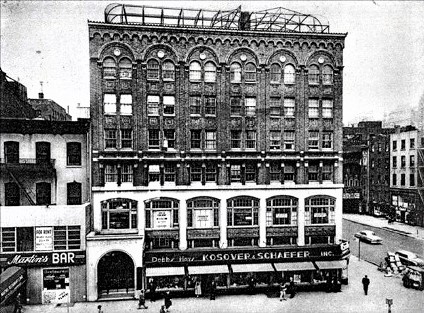

In 1924, the circa 1851 church building was demolished and replaced with a six-story building designed by Emory Roth. The new building featured a chapel, an auditorium, and a gymnasium for the temple, plus additional commercial space controlled by the developers.

The Labor Temple disbanded in 1957, after which the building was used by the Presbyterian Church of the Crossroads and, later, Congregation Tifereth Israel.

I’m not sure how long cats, dogs, and other animals were welcome at the Labor Temple, but I’m pretty sure as long as Dr. Stelzle was at the helm, the welcome mat was out for them.

I want to leave you with some closing quotes from Dr. Stelzle’s autobiography that caught my interest while researching this story. Like Dr. Stelzle, my intention is not to preach, but rather to provide some food for thought.

“We hear a good deal these days about the uprising of the radicals. But I am more concerned about the downsitting of the conservatives—those who are quite content with things as they are; who have comfortable homes, can afford to wear good clothes, are assured of enough to eat, can educate their children, and have snug little sums in the bank or in bonds which will provide for them in the future.”

“Social unrest is one the most hopeful signs of the times. Without it there can be no real progress. But this spirit of social unrest requires intelligence and unselfish direction…”

In 1924, Presbyterian Labor Temple occupied part of a new building at 242 East Fourteenth Street, shown here in the 1950s. The building is still standing, albeit now it is home to luxury apartments and a Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurant.

The Empire Poultry Show took place at the Grand Central Palace, which occupied the air rights over the railroad tracks leading into Grand Central Terminal (the entire block of Lexington Avenue between 46th and 47th Streets). Read the rest of this entry »

The Empire Poultry Show took place at the Grand Central Palace, which occupied the air rights over the railroad tracks leading into Grand Central Terminal (the entire block of Lexington Avenue between 46th and 47th Streets). Read the rest of this entry »