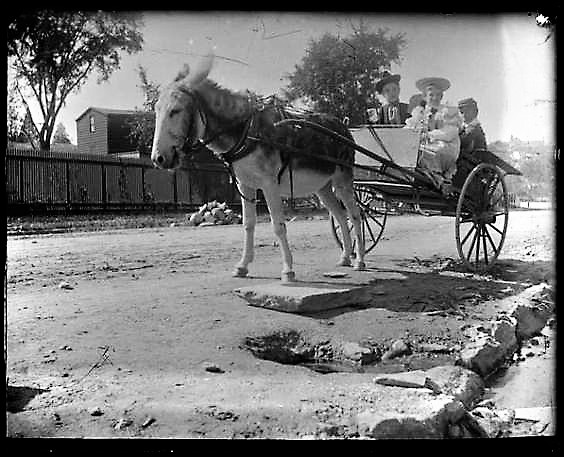

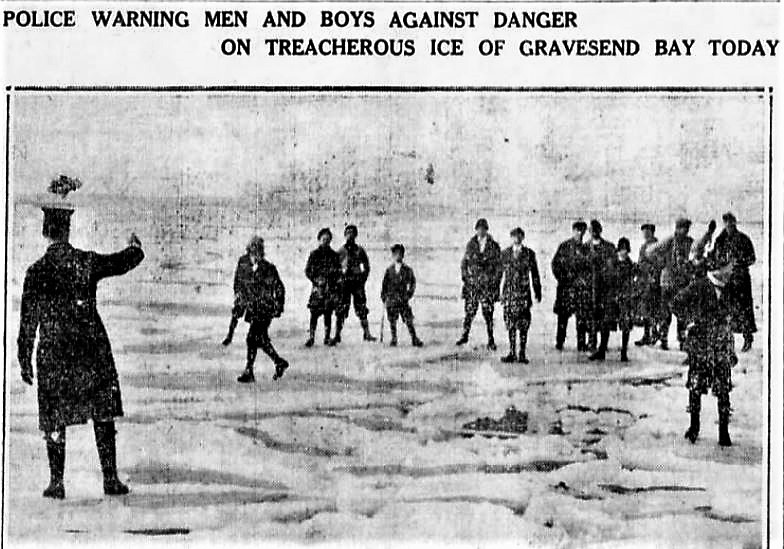

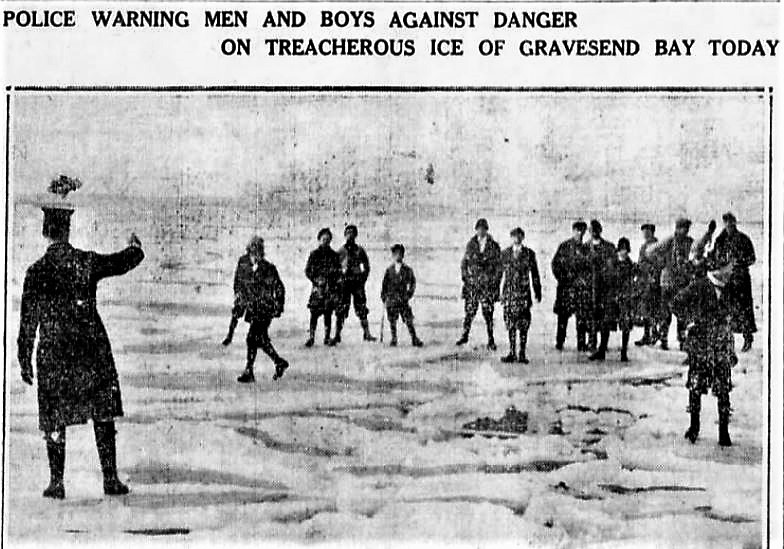

In February 1912, ice floes filled the Gravesend Bay and the Narrows, making it possible for hundreds of adventurous people to cross the bay to Norton’s Point on Coney Island. It was the first time since the great blizzard of 1888 that the waters froze enough to form an ice bridge made of giant ice floes.

NBC’s Katie Couric struck a nerve with the Dutch during the Pyeonchang Olympic Opening Ceremonies by saying the reason the Netherlands is so dominant in speed skating is because “skating is an important mode of transportation” for the people of Amsterdam when the canals freeze over.

There was quite a lot of backlash from the viewers, who pointed out correctly that not only do the canals rarely completely freeze over, but the Dutch usually get around like everyone else in the world, either by foot, bicycle, or car. Oh, and they also don’t wear wooden shoes anymore.

To be sure, there have been winters that were cold enough to turn Amsterdam’s canals into frozen skateways, but for the most part, the Dutch mostly rely on man-made ice skating rinks or frozen ponds for their skating pleasure.

New York City hasn’t had a canal system since the British filled in the canals of the city’s early Dutch settlement in 1676 (and the old canal that is now Canal Street was covered over in 1819), but the city is surrounded by water. And that water has frozen over several times in the past, most notably in the 1800s and early 1900s, before our winters got warmer and the shipping traffic got heavier.

Read the rest of this entry »