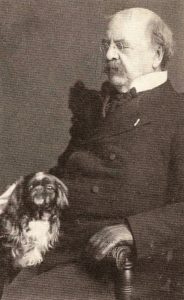

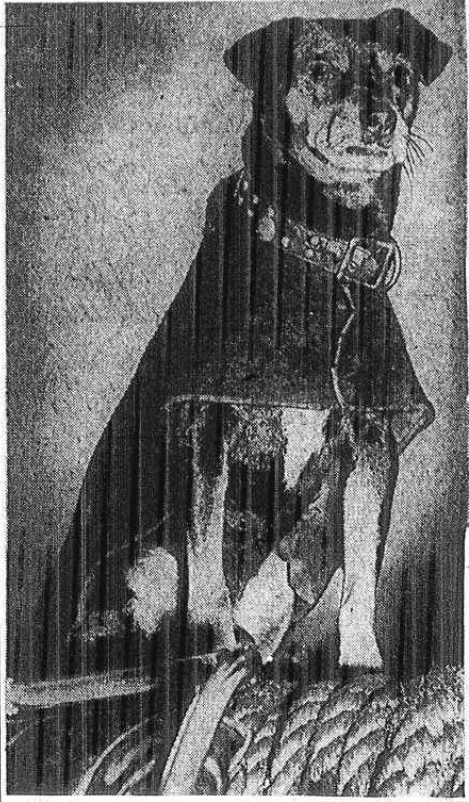

General Sickles with his Blenheim spaniel, Bo-Bo, sometime around 1904 in New York City.

“It is not surprising and will scarcely cause any comment if some soft-hearted or soft-brained woman goes into hysterics over the death of her pet dog or cat, and gives herself up to the most extravagant grief over his demise, but the spectacle of a veteran soldier who fought with distinction in the Civil War, doing the same thing, is rather strange.”—Arkansas Democrat, September 2, 1905

Born on October 20, 1819 (the birth year is not absolute), Daniel Edgar Sickles was the son of Susan Marsh Sickles and George Garrett Sickles, a New York City patent lawyer and politician. Much has been written about General Sickles, so for the purpose of this story, I’ll sum it up in one paragraph as follows:

General Daniel E. Sickles was a Tammany Hall politician; a murderer (in 1859 he shot and killed Philip Barton Key, the son of Francis Scott Key, but he was acquitted on the grounds of temporary insanity); a Civil War hero (he was awarded the medal of honor for his services at Gettysburg); a two-time Congressman; a good friend of the Princess Lwoff-Parlaghy (he purchased a lion cub for her in 1908 when she was living at the Plaza Hotel); and the owner of a purebred Blenheim spaniel named Bo-Bo.