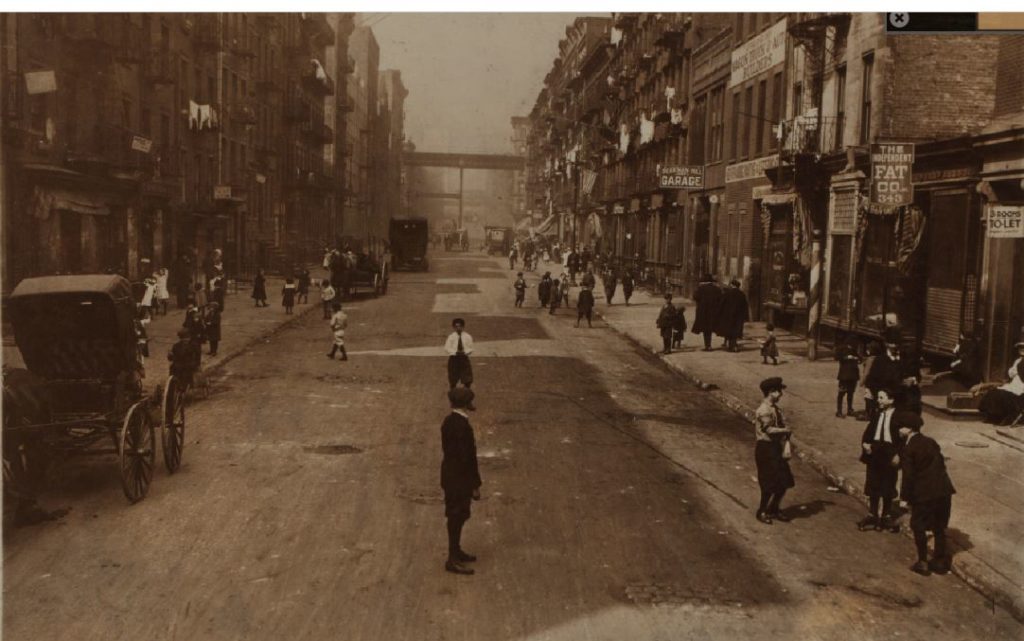

Tim and Tige lived and played on East 48th Street near First Avenue, pictured here in 1915. This neighborhood was razed to make way for the United Nations Plaza in 1948. NYPL Digital Collections

When we left Part I of this Old New York dog tale, little Tim Leahy had just been separated from his only friend, a Newfoundland named Tige. In Part II, we’ll travel to the southwest shore of Staten Island, to Father Drumgoole’s Mission of the Immaculate Virgin at Mount Loretto, a large, 600-acre farm for thousands of orphaned children and one very lucky homeless Newfoundland.

Read the rest of this entry »

In May 1895, the first official cat show in New York City took place at Madison Square Garden. More than 200 felines ranging from humble street cats (such as

In May 1895, the first official cat show in New York City took place at Madison Square Garden. More than 200 felines ranging from humble street cats (such as