Constructed in 1909, the large, block-long police station at 118 Clinton Street was quite the fortress, but it was simply not big enough to peacefully accommodate Buster and Topsy, the rival police cat mascots.

In December 1911, the policemen of the old Eldridge Street police station in New York City’s Lower East Side moved into the new station house constructed for the men of the old Delancey Street station. Although the new station at the corner of Clinton and Delancey streets was more than big enough to accommodate everyone, the rival police cats, Buster and Topsy, refused to share the same territory.

In Part I of this old New York City Police mascot story, we learn that the move to 118 Clinton Street was a disaster for the little male cat, Buster, who was clearly bullied by the much larger female cat, Topsy. One has to wonder if the outcome would have been different had the two feline mascots been of the canine persuasion instead.

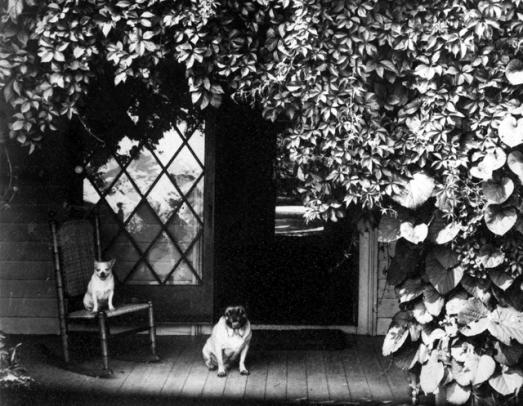

Chico and Punch, the two pampered pooches of photographer Alice Austen, on the porch of Clear Comfort, the 17th-century farmhouse on Staten Island where Alice spent most of her life. Chico and Punch lived with Alice for about 15 years, during which time she took many photos of them. Alice took this photograph in 1893.

Chico and Punch, the two pampered pooches of photographer Alice Austen, on the porch of Clear Comfort, the 17th-century farmhouse on Staten Island where Alice spent most of her life. Chico and Punch lived with Alice for about 15 years, during which time she took many photos of them. Alice took this photograph in 1893.