The following story about McLaughlin’s dog pit is not for the squeamish — it was not an easy story for me to write, but I think it’s an important story to tell as it says a lot about society in New York City just before and during the Civil War.

Hell in New York City

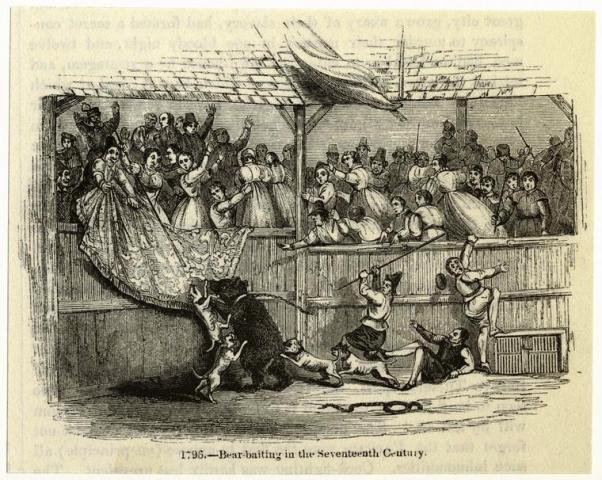

Three hundred beings human only in shape were crowded together in a close, noise some cellar only about 20 feet square, and a great part of that space was taken up by the pit Saturday night. The animals were tortured merely for the amusement of the spectators. The programme advertised three days beforehand: The sports of the evening would commence with bear baiting, badger and coon drawing, wolf hunting and rat killing.

The bear was baited by five dogs until he caught them in his paws and crunched them half to death, amid the yells and cheers of the assembled fancy. More than a dozen dogs baited the badger. There was also a match between two dogs who fought with such fury that in five minutes their passing could be heard above the shouts of their masters: and when they were stopped for a moment in one place, they marked it with a pool of blood.

The dogs fought for 20 minutes until they were helpless. The men kept cheering them on even though they were exhausted. Then a bag of rats was dropped into the pit, and men and dogs jumped in kicking. When all the rats were killed, a dog and raccoon were pitted against each other. This went on until early on Monday morning by a raffle for dogs still bleeding from the fights.– New York Tribune, January 29, 1855, “Hell in New York,” about a scene from McLaughin’s dog pit

The Dog Pits of New York City

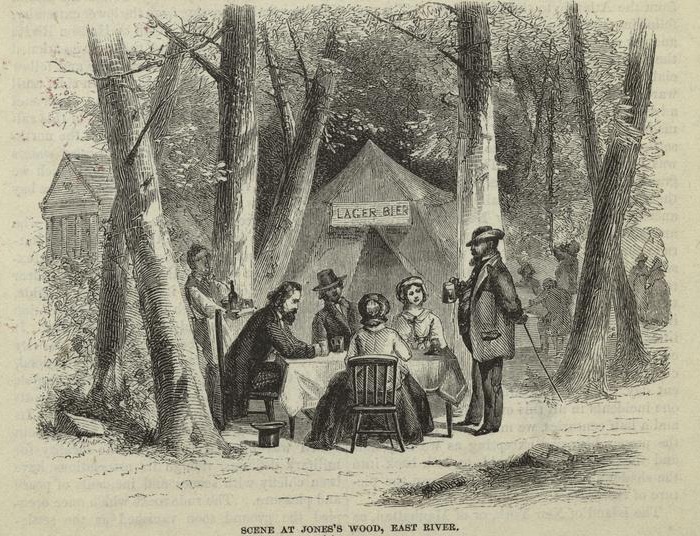

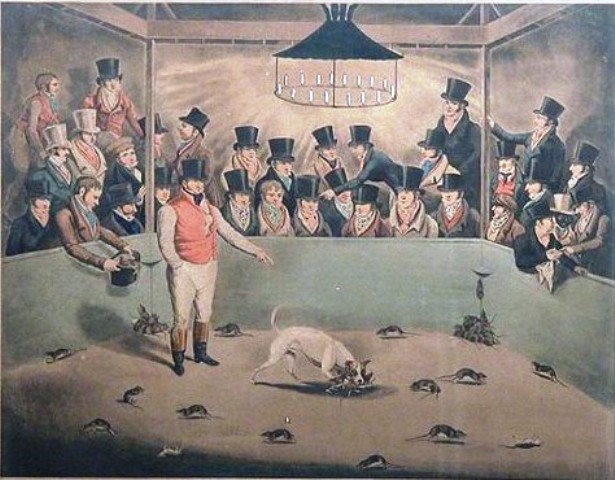

In the 1850s and 1860s a brutal pastime called rat-baiting reached new heights in popularity in New York City. Basically, rat-baiting involved pitting a dog against a rat until they fought to the death. When the rats did not provide enough excitement for the mostly young sporting men and male tourists who came to these events, other animals including raccoons, badgers, pigs, and sometimes a bear would take the place of the rats.

Oftentimes, champion dogs were pitted against other dogs. And later in the century it became popular to pit rats against men wearing heavy boots.

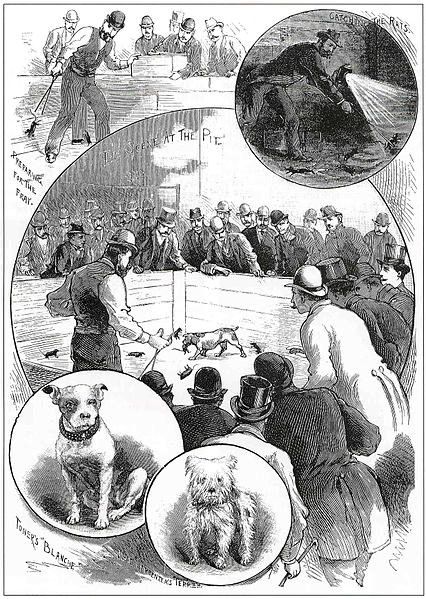

Rat-baiting events were not legal, but they were openly patronized and often advertised in publications like The New York Clipper, a weekly entertainment newspaper published in New York City from 1853 to 1924. Many ads for McLaughlin’s dog pit appeared during this time.

The dogs at these “sporting” events were, for the most part, terrier breeds who were trained for about six months and sent into the pit when they were about a year old. The rats were provided for free — neighborhood boys were paid to catch them, at a rate of 5 to 12 cents each.

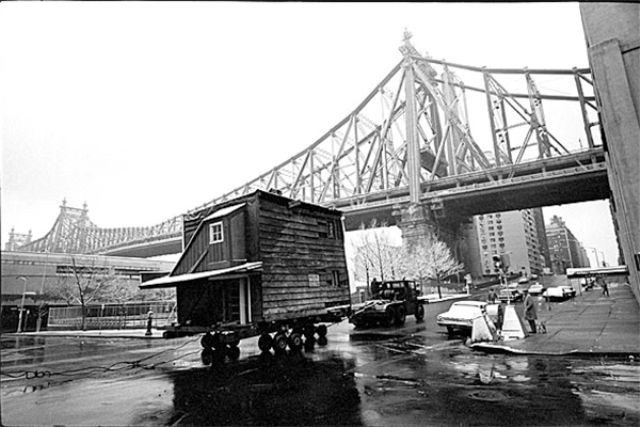

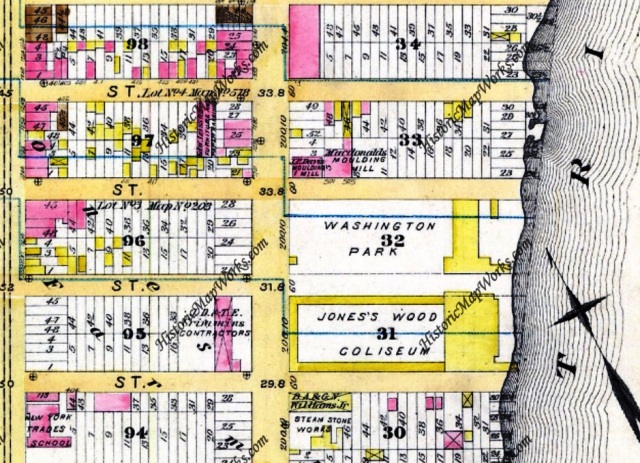

The dog pits, at places like McLaughlin’s dog pit on First Avenue, Kit Burns’s Sportsmen’s Hall at 273 Water Street, and Jacob Roome’s pit at 140 Church Street, were basically open wooden boxes with walls about 8 feet long and about 4 feet high.

James McLaughlin’s Dog Pit and His Champion Rat-Baiting Dogs

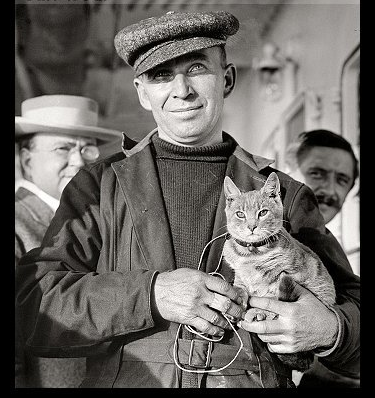

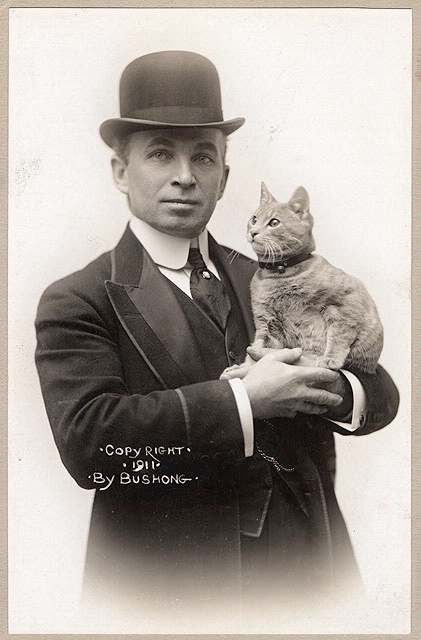

James McLaughlin was one of the most famous breeders of champion rat-baiting dogs. From about 1854 to 1859, he held “canine exhibitions” at his dog pit at 155 First Avenue. Oftentimes his own terriers, including Whiskey and Princey, participated in the events.

These events were usually advertised in The New York Clipper, such as this announcement that appeared in April 1859:

April 25, 1859 – A great canine exhibition on Easter Monday…Muzzles and silver collars, and prize for the dog who kills his five rats in the shortest amount of time. Princey, the champion at 24 pounds, open to fight any dog in the world for $100 or $200. Crib, 44 pounds, Billy, 18 pounds, Mr. O’Brien’s dog, Blinker, 15 pounds, Nelson and Fan of Staten Island, Dick of Newark, Sailor of Brooklyn, the slut Lady, the slut Rosy of Brooklyn, the Yorkville slut. Weighing to commence at 7 p.m., the show started at 8 p.m. Tickets 25 cents. Collars and rats free of charge.

Another announcement read:

A Grand Ratting Exhibition will be given at James McLaughlin’s Sportsman’s Retreat, 155 First Avenue, on Friday Evening, May 26, 1854. There is 4 handsome collars to be run for; 200 Rats to be killed, this is a real chance for gentlemen wishing to try their Dogs, as Collars and Rats will be given free. On that night there will be 10 Rats for large Dogs, and 8 Rats for small dogs; the Dogs making the best time to receive the Collars. The Badger Sport will be beated for a handsome Collar; the Bear and Coon will be on hand. Doors open at eight o’clock.

Sometime in January 1855, a Russian bear named Dennis was reportedly baited at McLaughlin’s dog pit. I don’t know the fate of the bear or the dogs that attacked it. But I do know that shortly thereafter, James McLaughlin and 30 spectators were arrested by the police of the 17th Ward. McLaughlin was charged with keeping a disorderly place and was held on $300 bail.

I don’t know if it was this arrest that changed his career path, but I do know that in the 1860s McLaughlin renamed his place Union Hall, which featured sparring events with men only. In later years, McLaughlin continued breeding terriers, but for the dog show circuit at Madison Square Garden as opposed to the rat-baiting circuit.

A Brief History of First Avenue

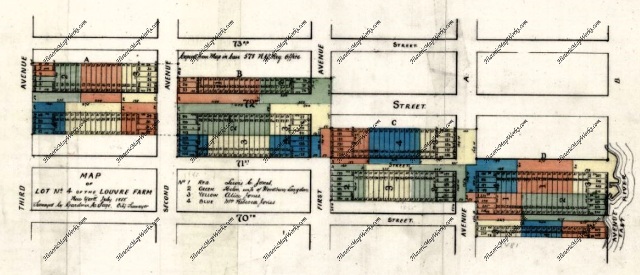

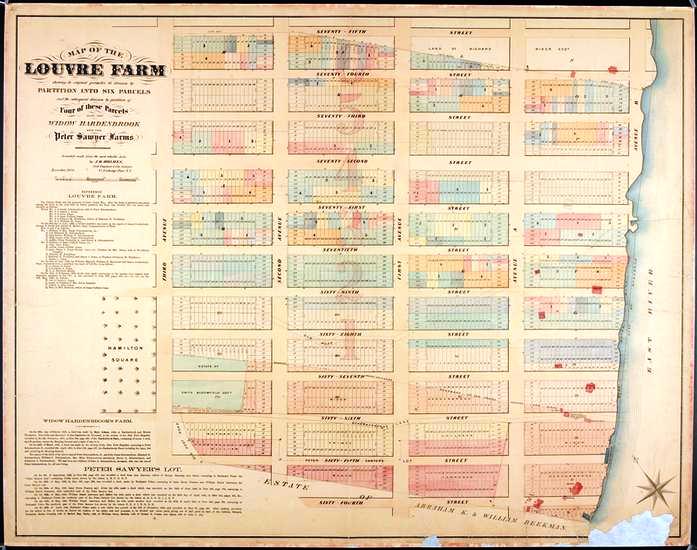

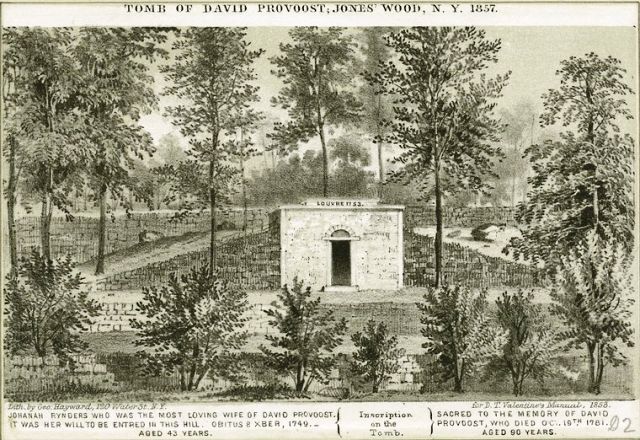

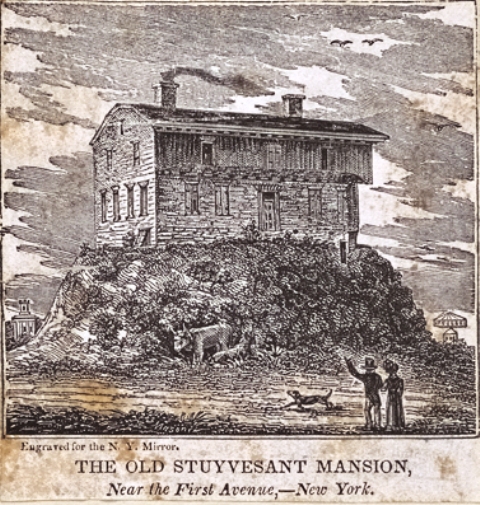

When Petrus Stuyvesant, the last Dutch Director-General of New Netherland, surrendered to the British in 1664, the King offered him a 62-acre tract of land on the lower east side of New York. Stuyvesant established his country seat on his Bouwerie (or Bouwerij, the Dutch word for farm), which covered what we call today the East Village and Stuyvesant Town (from about 6th Street to 23rd Street, between Fourth Avenue and Avenue C). He named his home Petersfield.

Stuyvesant built his home on a high slope facing the East River, right about where today’s First Avenue intersects with 15th and 16th streets. He lived in the home until his death in 1672.

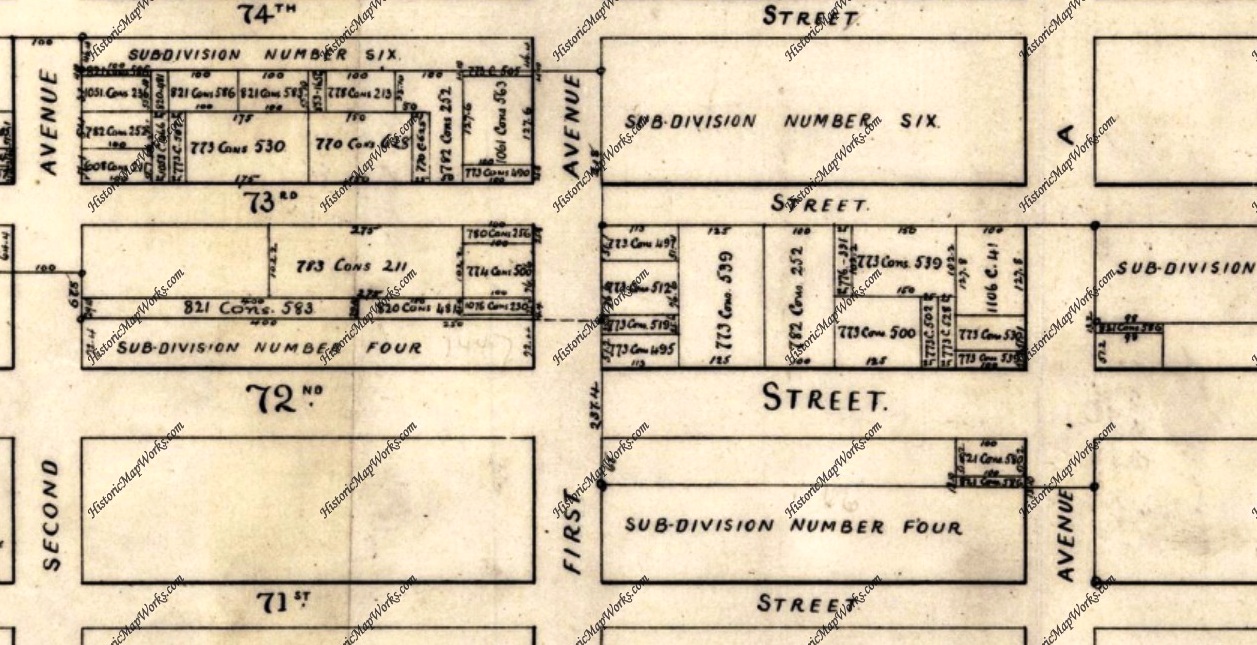

More than 100 years after Stuyvesant’s death, First Avenue was one of the 12 north-south avenues proposed as part of the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 for Manhattan. The southern portions of the Avenue, where Stuyvesant’s old home was located, were cut and laid out shortly after the plan was adopted.

In 1831, an article in the New York Mirror reported that the Stuyvesant house was still standing, albeit, “it appeared to be tottering on its ancient base” as all the earth around it was being removed to use as landfill in other areas. According to the article, the two-story house with gambled roof was constructed of brick painted yellow. Part of the building on the northeast corner had fallen down, and its demise was imminent.

For almost three centuries, the Stuyvesant farm remained in the family, although little by little, parcels were sold off for development.

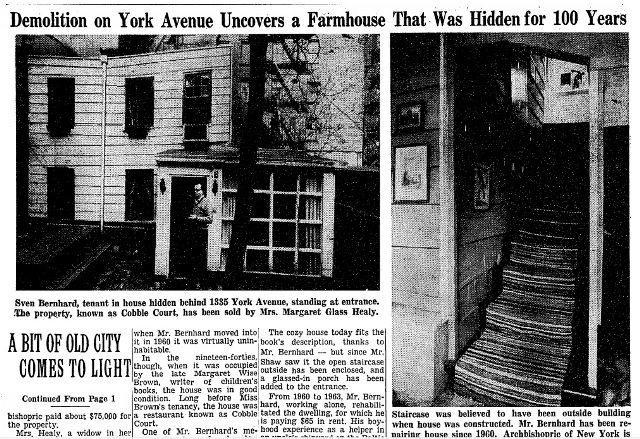

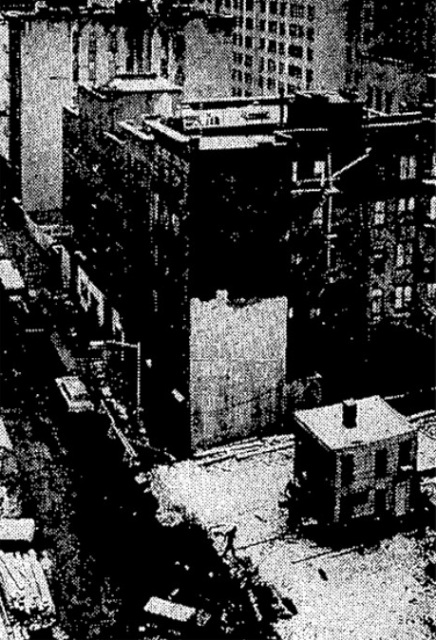

In 1820, Peter Gerard Stuyvesant sold 60 lots adjoining First, Second, and Third avenues from 10th through 13th streets. Based on this account in The Evening Post (November 18, 1820), the five-story with basement tenement at 155 First Avenue was probably constructed around this time.

155-157 First Avenue

In the early 1900s, First Avenue from about 1st to 14th streets was filled with peddlers and their pushcarts. Mayor Fiorello Henry LaGuardia, elected to office in 1934, removed the pushcarts from city streets and abolished the city’s filthy, crowded open-air markets.

In place of the open-air markets and pushcarts, LaGuardia used federal Works Progress Administration funds to build several indoor markets that had running water and loading platforms. In 1937, architects Albert W. Lewis and John D. Churchill were commissioned by the Department of Markets to design several of these markets, including the First Avenue Retail Market.

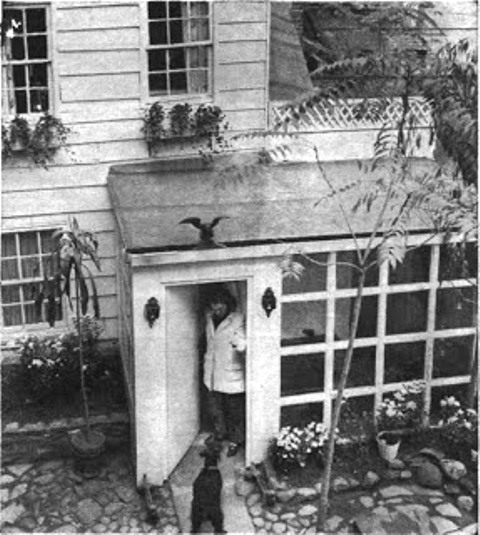

Constructed in 1938, the indoor market occupied an L-shaped building that spanned 155-157 First Avenue and 230-240 East 10th Street. Where once terrier dogs fought rats and bears, there was now a bustling neighborhood market where merchants sold cheese (the rats would have loved that), vegetables, and other grocery products.

When the market closed in 1965, the city’s Sanitation Department took over the 30,000 square foot building for use as a storage warehouse for paperwork and small equipment. The Sanitation Department was the sole occupant of the building until 1987, which is when Crystal Field and her husband, George Bartenieff, moved in with their small theater group, the Theater for the New City.

Founded in 1970, the Theater for the New City is, according to The New York Times, “Off Off Broadway’s answer to the mom and pop grocery.” According to the theater’s website, each year TNC produces about 35 new American plays by emerging and established writers and theater companies that have no permanent home.