“I am heartbroken. I loved him as much as a human being, and he had more intelligence than a good many human beings and was far more faithful.”–Mrs. John T. Stephens, July 12, 1900, on the death of Major Van Buren Stephens

In July 1900, Mrs. John T. Stephens lost the canine love of her life. Having lost her young son just two years before, the death of her dog Major was more than she could bear.

Major, an eleven-year-old brown and white collie, entered Myra Stephens’ life when he was only three weeks old and she still went by the maiden name of Myra Van Buren. The aspiring actress from Louisiana (her stage name was Myra St. Maur) raised Major and his brother on her own until her marriage to John Stephens, a wealthy produce merchant, in 1891.

During their early married years, the Stephens traveled extensively throughout Europe, the United States, and Mexico. On every trip, Major was at their side (I don’t know if his brother also traveled with them).

The childless couple doted on Major, teaching him over 50 tricks (according to Myra he could “talk in a way” and sing in three languages) and letting him dine with them at the table. Major was especially fond of coffee — every morning a servant brought him coffee in his bedroom, but he would not drink it until a napkin was tied under his chin. After he finished, he’d hold up his mouth for someone to wipe it.

Major was also a big hit with the residents of London Terrace, a set of 36 grand brownstone row houses on West 23rd Street between 9th and 10th Avenue, where Myra and John Stephens made their home.

Sometime around 1895, Myra gave birth to a baby boy. Major instantly bonded with the child, and they became best friends.

According to Myra, in 1897 Major saved a young boy from drowning in Atlanta, Georgia. For his heroics, the father of the boy presented the dog with a gold medal. A year later, Major saved two other little boys from drowning at Rockaway Beach in New York.

That same year, in 1898, the Stephens lost their young son, leaving a huge void in their lives.

Major’s Passing

In July 1900, Myra Stephens took Major to the New York Veterinary Hospital, located just a few blocks away at 117 West 25th Street. Major was not treated by chief surgeon Dr. S. K. Johnson, but Dr. Edward M. Leavy — also a very experienced surgeon — did his very best to treat the collie in his final days.

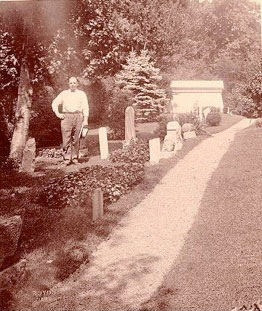

The Stephens chose to bury their cherished dog in a small pet cemetery that had once been Dr. Johnson’s apple orchard in Hartsdale, New York. On the day of his funeral, Major was washed, combed, and placed in a satin-lined rosewood casket. The casket featured four silver handles and an oval glass plate at the top for viewing.

A gold collar adorned his neck, and flowers covered his body. As the Stephens’ many friends came to call and place more flowers on the casket, Major’s surviving brother collie stood by and howled.

Major was taken by an animal ambulance to Grand Central Station, where the casket was placed on a Harlem Line train bound for the Hartsdale Pet Cemetery in Westchester County.

The Clement C. Moore Estate at Chelsea

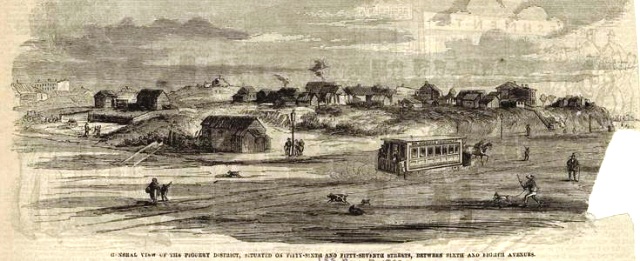

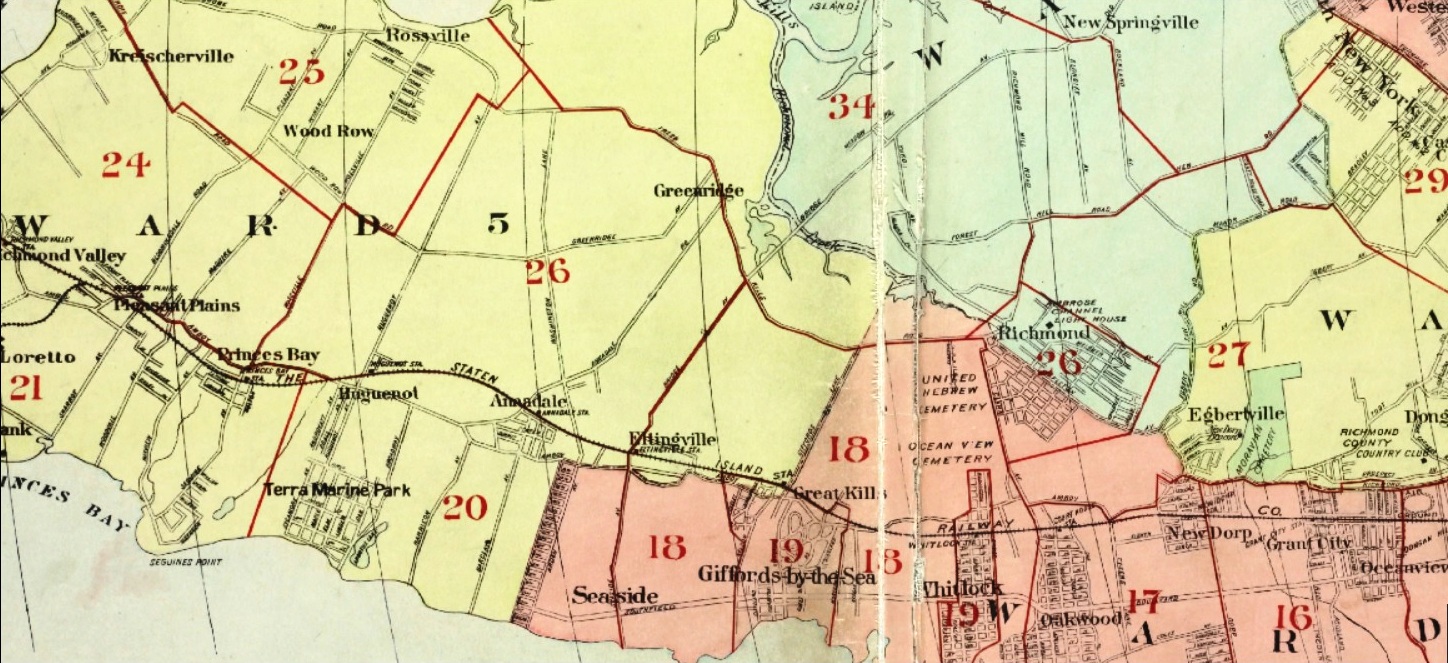

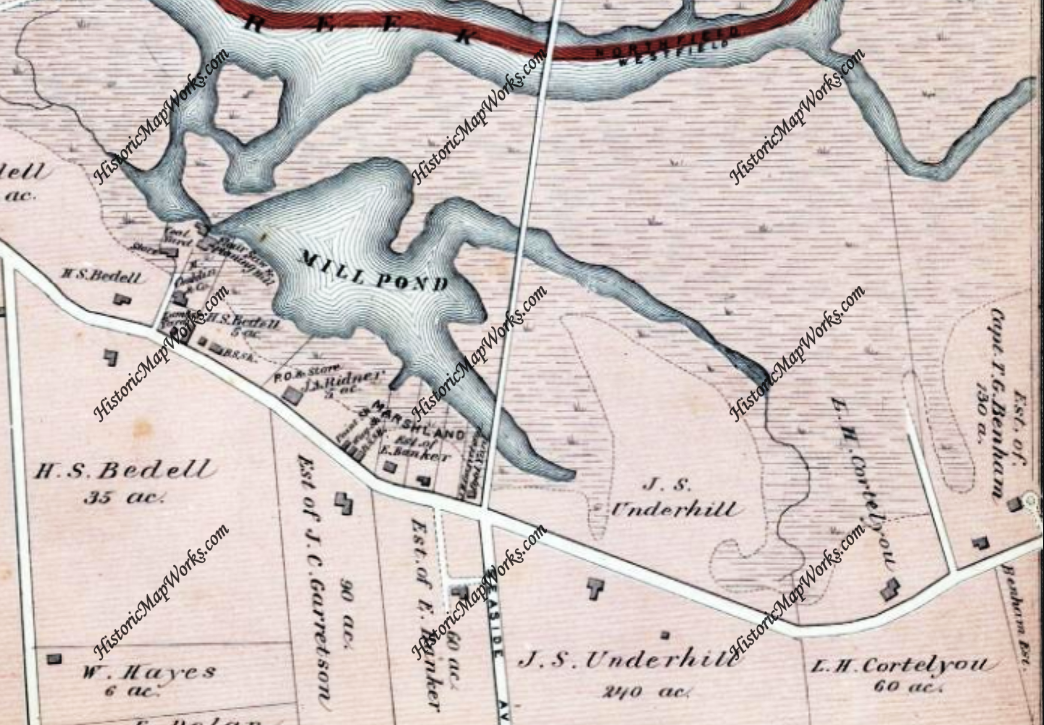

For several years, Major and his brother collie lived with the Stephens at 427 West 23rd Street, which was then one of a group of brownstone townhouses called London Terrace. The property has a very interesting history, dating back to the 17th and 18th centuries, when the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan was all hilly forest and farmland owned by Jacob and Teunis Somerindyke.

This large farm of several hundred acres was bounded by what was then called the North River (Hudson) and 8th Avenue (then called Fitzroy Road) from 14th to 24th Street. The land featured a river that flowed near present-day 10th Avenue and a small creek by the shoreline at 22nd Street.

Chelsea House was on a high bluff overlooking the Hudson River, near today’s West 23rd Street between 9th and 10th Avenue.

Chelsea House was on a high bluff overlooking the Hudson River, near today’s West 23rd Street between 9th and 10th Avenue.

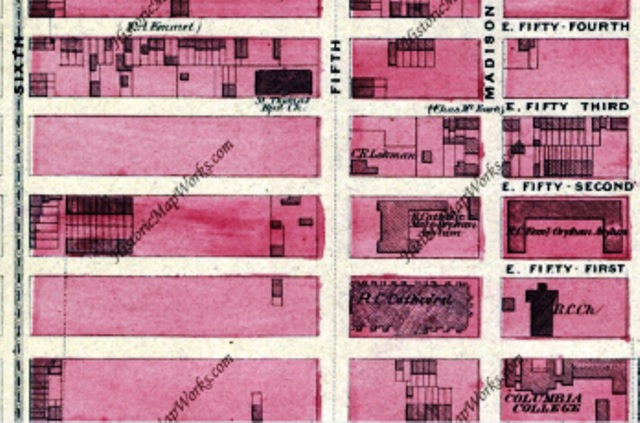

In 1750, Captain Thomas Clarke, a retired British military man, bought a large piece (about 100 acres) of the old farm and named it Chelsea, after his native London’s Royal Hospital at Chelsea, where old soldiers lived out their final days. There, near the intersection of today’s 8th Avenue and 24th Street, he built a “snug harbor” that he called the Chelsea House.

In 1776, the year Captain Clarke died, a fire destroyed the three-story frame house. His widow, Mary Stillwell Clarke, replaced it with a larger brick and stone Chelsea House near what would now be lots 422 and 424 on West 23rd Street.

Mary defended the house against the British troops during the Revolutionary War, and remained there until her death in 1802.

The house and much of the property stayed in the family, passing to Mary’s daughter, Charity, and her husband, Benjamin Moore, the Episcopal bishop of New York and president of Columbia College. Chelsea House was commonly called The Pulpit during the bishop’s residency there.

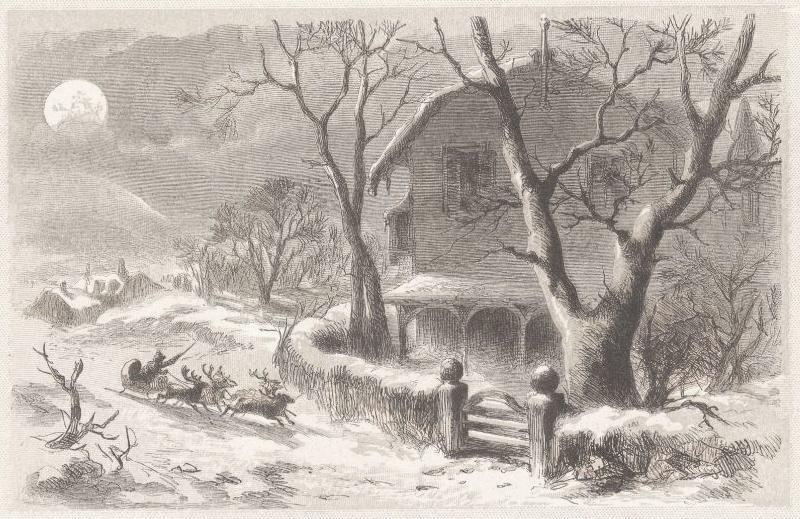

In 1779, Clement Clarke Moore was born in Chelsea House. Here, in 1822, he first recited the poem he wrote for his two daughters — “A Visit from St. Nicholas” — the classic holiday poem that begins, “T’was the night before Christmas, when all through the house…”

Legend has it that Moore wrote the poem while on an errand during a snowy night in Greenwich Village, buying a turkey to give to the poor. He was supposedly riding a sleigh pulled by a horse with jingling bells.

Moore may have based his Santa Claus on the family’s jovial and plump Dutch handyman, or possibly his friend Washington Irving. The poem was first published in Troy, New York, in a newspaper called the Sentinel on December 23, 1823.

Sometime around the 1830s, Moore began dividing his land into lots and selling them for fine residences.

In 1845, working with William Torrey (who leased the land), Moore erected a large housing development called London Terrace and Chelsea Gardens, which encompassed West 23rd and 24th streets between 9th and 10th Avenue.

Then in 1853 he razed the family seat (Chelsea House) across from London Terrace and sold the land. On that site, elaborate row houses later called Millionaires’ Row were constructed.

Moore moved into a new townhouse on West 22nd Street, where he lived until his death in 1863. This house is still standing today.

In 1907, a financial panic marked the beginning of the downfall for the 1845 London Terrace. The once pricey one-family homes were subdivided into rooming houses and apartments.

Extra floors were added to several of the buildings, and some were converted to institutions (for example, the townhouse where the Stephens once lived was once occupied by the Florence Crittenden Home for Girls; three London Terrace homes near 10th Avenue were combined with three of the Chelsea Cottages to form the School for Social Research campus.)

By 1929, developer Henry Mandel had acquired control of the block — well, all of the buildings except the house at 429 West 23rd Street. As Mandel began demolishing all of the buildings, Tillie Hart, once the next-door neighbor of the Stephens, held her ground, barricading herself in and refusing to leave until the sheriffs forced her out in October of that year.

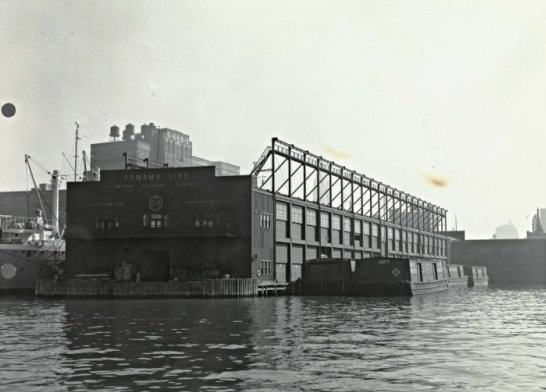

Mandel replaced the old townhouses with ten apartment buildings and four taller tower-like structures at each corner. The buildings contained 1,665 apartments, plus an abundance of amenities such as an indoor swimming pool, supervised rooftop play area, gymnasium, penthouse recreational club, sun deck for infants, courtyard garden, and a rooftop marine deck furnished to look like an ocean liner.

The Passing of Myra Van Buren Stephens

In the years following Major’s death, Myra Stephens became more attached to dogs and less attached to the real world.

In February 1904, she headed up an enterprise called the Idlewild Canine Cemetery Association. The association reportedly purchased five acres of land just north of the train depot in Central Islip for use as a cemetery for poodles. There are no further reports of this dog cemetery (although I did find this recent story about a woman charged with having a pet cemetery in her Central Islip yard. Hmm…)

In 1920, while living in a friend’s 17-room house at 1155 Guion Avenue (108th Street) in Richmond Hill, Queens, Myra was charged with keeping numerous dogs in a boarding kennel without a kennel permit. By this time her life had taken a turn for the worse, and she was often seen knocking on theater stage doors and begging for assistance from the actors and actresses.

On November 12, 1931, the sound of whimpering dogs got the attention of a policeman, who broke into Myra’s squalid, six-room tenement apartment at 1250 Second Avenue. There, Myra was found dead on the floor surrounded by her 11 dogs. Myra was taken to the city morgue and the dogs were taken to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Major’s old home at 427 West 23rd Street is now part of London Terrace Gardens.

Major’s old home at 427 West 23rd Street is now part of London Terrace Gardens.